Ahead of a major upcoming exhibition at UCCA Beijing, curator Holly Roussell ruminates on the significance of the slideshow in reform-era China

China underwent tremendous social change in the late 1970s and 1980s, ushering in a new period of artistic experimentation. Following the Cultural Revolution, the country steered towards modernisation and a market economy under the new Open Door Policy, spearheaded by Deng Xiaoping.

Encouraged by the reopening of art academies, and the increased potential for international exchange, independent art groups and exhibitions began to flourish across the country. Consisting of primarily self-taught artists, the first wave of groups (active in the late 1970s), including the Stars Art Group and the April Photography Society, organised exhibitions outdoors in parks or at cultural centres. Soon, however, artists of what would be referred to as the ‘85 New Wave would exhibit more regularly in unofficial gallery spaces and the occasional museum. This surge of activity was characterised by a focus on individualism and experimentation in art. Hundreds of young artists were seeking to break with the strict socialist realism style that had been dominant in China during the preceding decades, pushing the limits of art by exploring new potential concepts, forms and media.

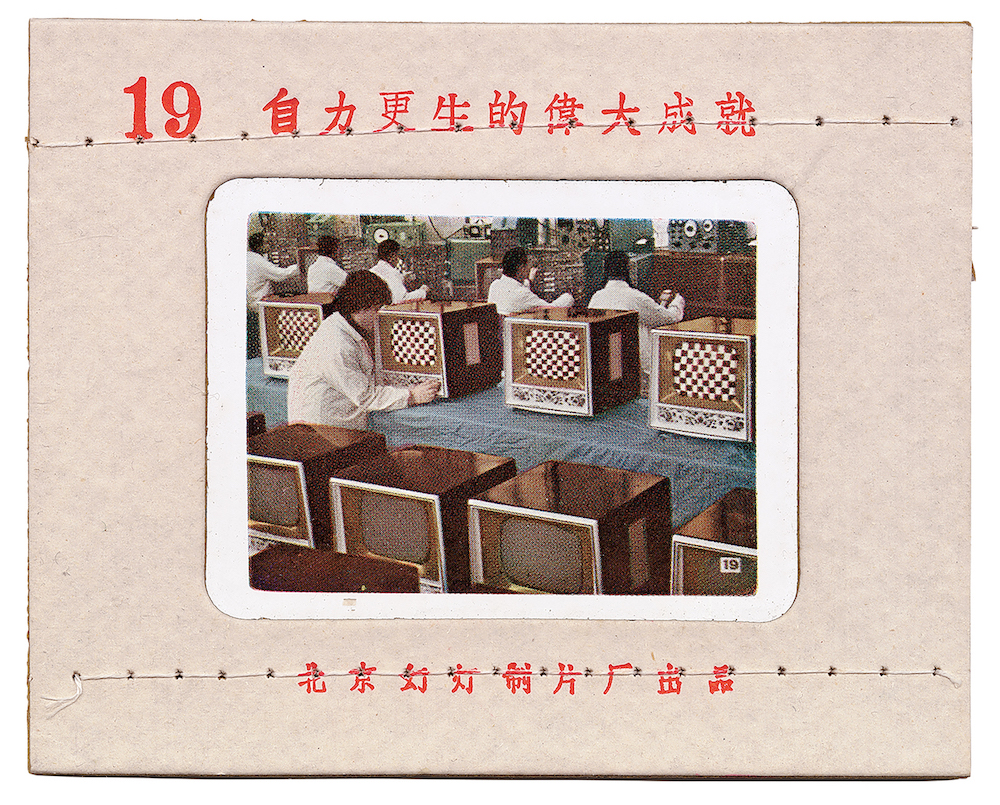

Portable and reproducible, the photographic slide was central to this evolving landscape. The subsequent decade brought art historical texts and images from beyond China’s borders into the country, introducing a new range of cultural references. Before the internet, slides gave artists, historians and curators new access to art produced elsewhere; many used them to share their work more broadly. Simultaneously, the export of artworks by emerging Chinese artists into the global market meant that they entered the wider contemporary art discourse for the first time.

In the exhibition Slide / Show, which opens in April at the UCCA Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing, we present a unique perspective on this period of Chinese art history by exploring the various applications of projected photography spanning from the 1950s to the 2010s. During these years, artists became acutely aware of lagging behind the West. Rather than feel intimidated, they avidly consumed the new information and technologies while also questioning their relationship to the canon of Western art history. Over the second half of the 20th century, projected photography transitioned from a tool into an artistic language in its own right, as Chinese artists became active participants within the international art market.

Organised around key characteristics of the slide – specifically its transparency, refraction and use in transmission – the upcoming exhibition guides the viewer through a unique history of projection in China. Performance, though not the subject of the exhibition, is a current running through many of the early experimental artworks shown.

Photographic images serve multiple roles in this exhibition in relation to performance and, in some cases, they represent the language of expression, the subject, and the documentation. Freely engaging with new forms of expression, technologies and media, it is clear that, for artists such as Lin Jiahua, Song Dong, or Zhang Peili, the combination of performance and projected photography held particular significance as a means to show their art to audiences, and to establish connections to the world.

Performing the slideshow: Zheng Shengtian to Lin Jiahua

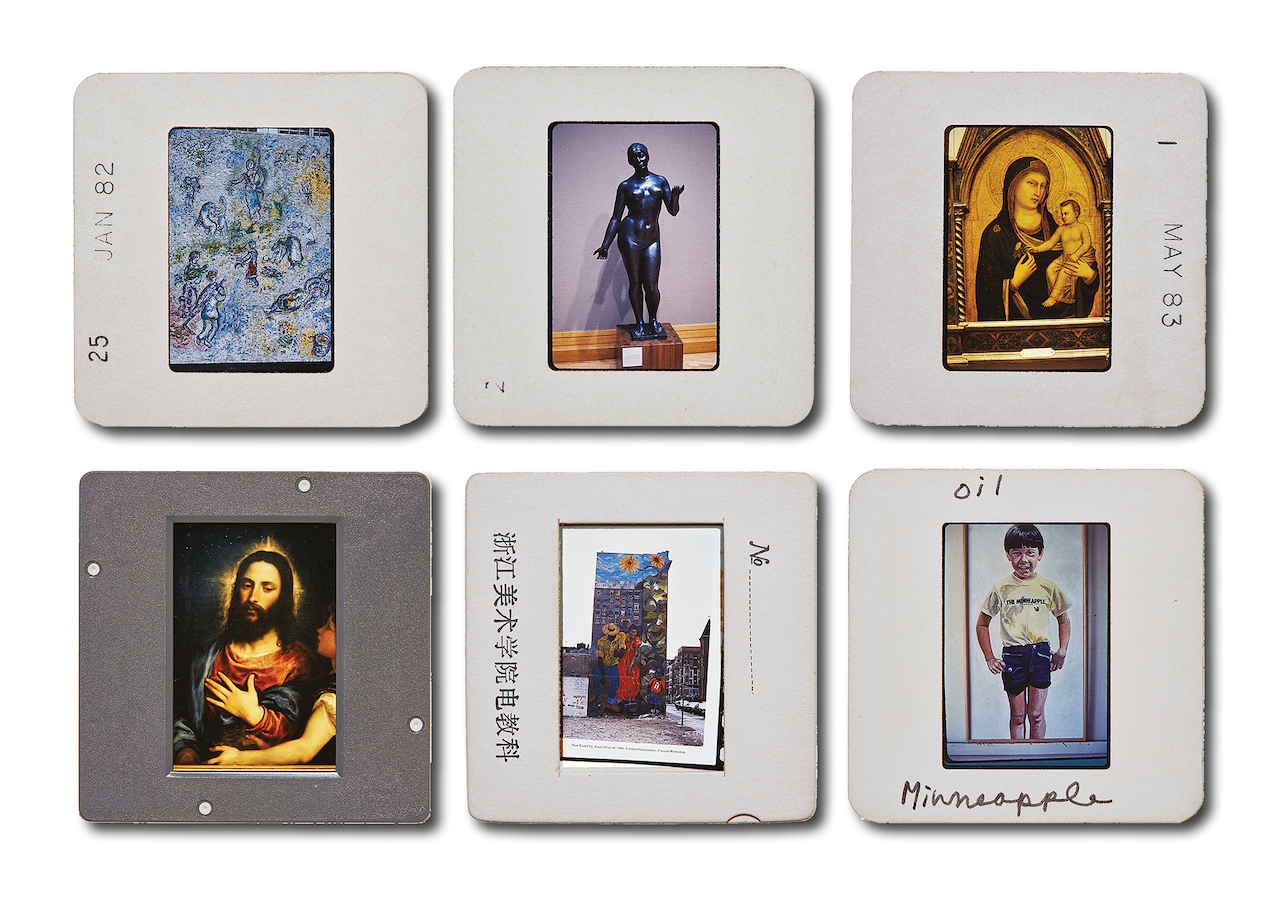

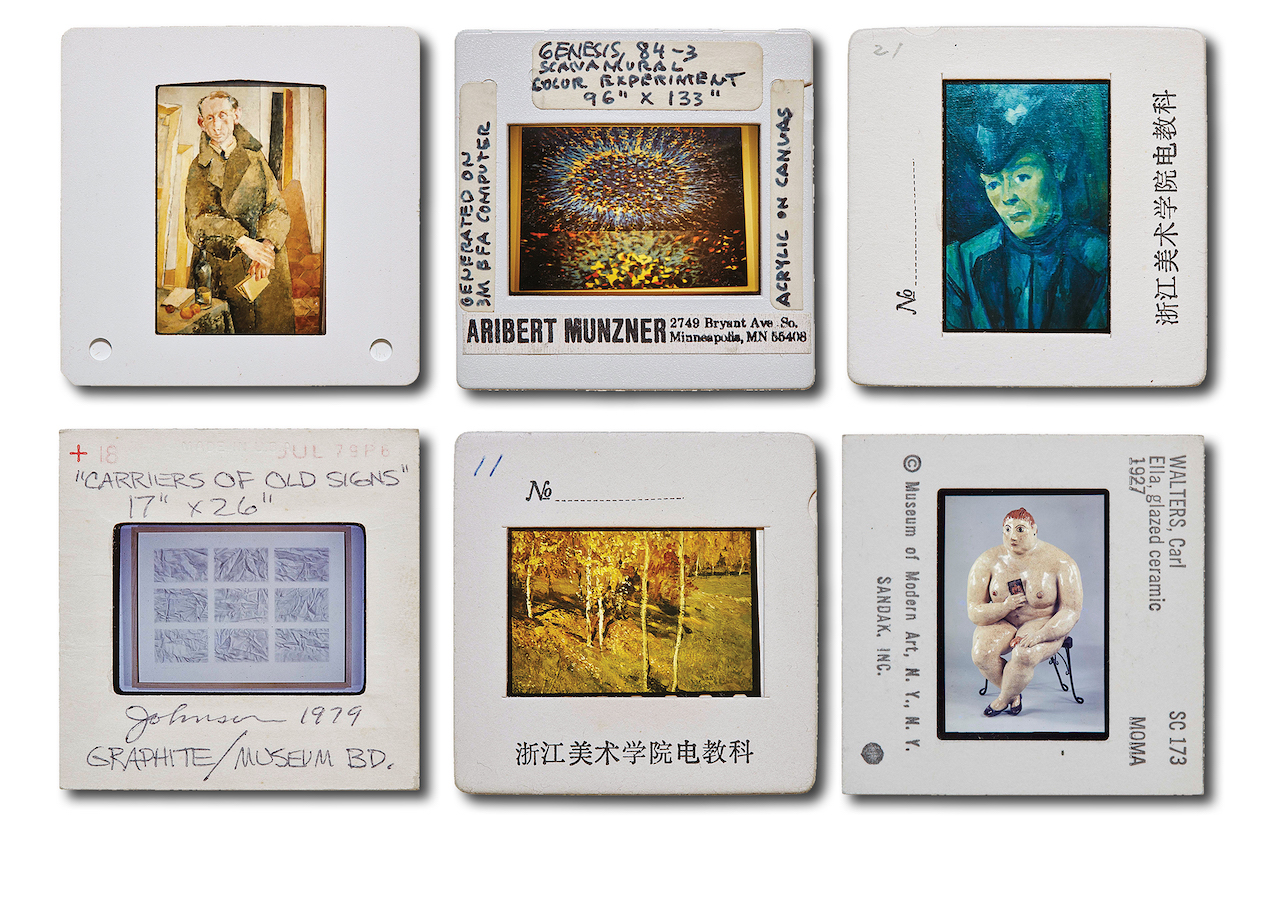

medium for artists in China to learn about art produced outside the country, as well as to promote and share their own work. It became common practice during this time to organise group ‘slideshow events’ on the occasion of a visit by a curator to a city, or simply as part of a dialogue between artists. This new form of gathering gained popularity in the mid-1980s. A leading figure in the history of slideshows in China was Zheng Shengtian. In September 1981, he was invited to the University of Minnesota as a visiting professor. He was one of the first art educators to participate in an official exchange of this nature. Zheng returned to China a few years later with thousands of slides he made himself, or from museums in the US, Canada, Mexico, Russia and Europe. He was invited to give lectures about Western art and life at art academies around China, and also shared his experiences with friends and colleagues.

For many, these slideshows were the first time they had encountered any art historical masterpieces in colour. At that time, although travelling slideshows were of great interest to artists, China did not yet have the extensive and efficient transportation network it has today. Artists saw slides as the best way to get their work seen by art academies and magazine editors. Many artists began to produce their own, carrying or shipping them by post to influential writers and curators.

One of these individuals was Fei Dawei, a professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. In 1986, Fei was invited to France to lecture on Chinese art. He brought with him more than a thousand slides, including works by the ’85 New Wave and some ‘official’ works by ‘professional’ artists recognised by the Chinese art establishment. These slideshows greatly influenced exchange between the two countries, and were key in the later inclusion of Chinese artists in the Centre Pompidou’s historic 1989 exhibition, Magiciens de la Terre.

In the Chinese context, slideshows represent a condition of possibility for the most important events in the development of contemporary art between 1985 and 1989. In addition to educating the first generation of artists following the Cultural Revolution, and in creating pathways for exposure abroad, the conceptual groundwork for the identity of Chinese contemporary art is inextricable from the domestic slideshows of the late 1980s. In August 1986, an event commonly referred to as the Zhuhai Conference took place. It was a major openforum slideshow viewing of contemporary art practice in China attended by historians, critics and artists. A few years later, an idea sown during that slideshow event – the hosting of an exhibition – would concretise during the Huangshan Conference. The status of art in China was debated at the event, and a multi-hour slideshow was presented to choose participants for the upcoming exhibition at the National Art Museum of China (Namoc) in Beijing, titled China/Avant-Garde (February 1989).

The exhibition is widely considered one of the most significant in the history of contemporary Chinese art, including some 300 works by 170 artists created between 1985–89. These slideshow gatherings served a crucial function, but their popularity quickly rose and faded. Initially lauded by artists, the lecture-style performances came to be associated with an institutionalisation of ideas and compartmentalisation of the true experimental nature of their practice

In 1988, the culture of slideshow presentations within the art community inspired an iconic performance by Xiamen Dada artist, Lin Jiahua. The To Enter Art History [above] slideshow event took place in south-eastern China. Illuminated by the projector’s beam, Lin moved from standing to crouching positions as he submitted his body as screen for a slideshow of Chinese and Western art historical masterpieces. Associating the slides with his physical body using light projection, Lin situated himself as a receptor for art historical knowledge. His work highlighted the role of his generation, and that of the group he associated with – Xiamen Dada – and the position of the individual in defining the future of Chinese art vis-à-vis art history.

In hosting a private slideshow, the artist positioned himself directly in contrast to the large touring slide exhibition events. Lin asserted the status of artist as palimpsest. His body, and what that body represents beyond his own personhood, becomes a surface upon which the contemporary and cumulative knowledge of history meet. The transparency of the projected slides reinforces the transitory nature of such influences. One cannot help but see a parallel between the young Xiamen-based performance artist, stripped to his underwear, and the Christian saviour. Lin thus called into question the ‘global’ canon of art history and personifies an alternative, hybrid mode of artistic development in this ephemeral slideshow event – a space where different art histories can be imagined to exist simultaneously. The sole audience for Lin’s event was his photographer: Wu Yiming. The event prompts the question of what a slideshow event is if it has no wider audience?

Performing with transparency: Song Dong

In the second half of the 1990s through the early 2000s, Chinese artists who were educated by slides went on to pioneer the next decade of art involving transparency. During these years, many artists travelled abroad for the first time, and the single-channel video piece and installation art became increasingly prominent in China. The attraction of a light image, whether transparent (such as lightboxes), as seen in the iconic work of Wang Wei, 1/30th of a Second Underwater (1999), or as projections onto different ‘screen’ surfaces, as in the work of Wang Gongxin or Zhu Jia, offered artists an expansive new means of expression.

Transparency, photography and performance were integral to the development of the Beijing-based artist, Song Dong. Employing materials accessible to him through friends or in his work as a teacher, his first performative artworks drew on the potential of projected photography to address the complexities of familial relations. In Touching my Father (1997) [above], Song photographed his hand touching the air in the dark, then subsequently projected that image onto his father’s body. Starting from the face, Song’s projected hand moved slowly across his father’s body until eventually it stopped at his father’s heart. Song recalls, looking back at this early work, how the ‘touching’ of his father in this way was the closest he had been to physical contact with him since childhood, and that it changed their relationship in the future.

In the performance, the artist uses the potential of transparency to suggest another version of himself, creating a sensory event while remaining separate from the projections of his body. The hybridisation of performance and projected photography allow the artist to approach ‘becoming’ an image. Emanuele Coccia has expressed this idea in reference to one’s image in a mirror, “an exercise in relocation and dislocation, but moreover in multiplication of self” (as written in Sensible Life: A Micro-ontology of the Image). Much as one multiplies the self in the mirror’s reflection – a support that interested Song in later years – Touching my Father uses projected photography as a form of multiplication. The second-self, a photographic hand, is still sensibly an artificial entity, unable to exert material contact. However, the movement of the light image over his father’s body, an atmospheric and intangible touch, still licensed new sensations and a new relationship between artist, medium and subject. Using superposition of past and present in the performance works with his father throughout the 1990s, Song exploits the projection’s unique capacity to layer images, multiply them and evoke emotion.

Light images are a paradigmatic medium for further exploration – associating many forms while remaining unrestrained by a singular designation. Fittingly, narrative resolution is not always the ultimate goal of the works shown. The Slide / Show exhibition casts a wide net to further illuminate non-linear connections between lived experiences, media and technologies, and to emphasise subtle links between entertainment, political and cultural messaging forms and art-making. Artists active in this fertile period of development in China sought to question what we see, how we visualise, how we learn, as well as to interrogate the quotidian actions that make up our lives. Performance, projection and photography hold a unique place within this history, and Slide / Show posits to elucidate a new genealogy of the medium in the post-Mao context.

Slide / Show is on show at UCCA Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing, from 29 April to 13 August 2023.