Photography by Samira Kafala.

The South African mixed media artist invites us into his Amsterdam studio where imposing collage canvases depicting everyday domestic life take centre stage

I cycle to Neo Matloga’s Amsterdam studio on the morning of my 29th birthday. Keen to live up to emailed assurances, I make a pitstop en route for a box of macarons. In the Netherlands, a binding social custom charges celebrants with bringing their own birthday cakes to work. From Centraal Station, a passenger ferry carries me northbound, traversing the IJ river to the city’s NDSM neighbourhood. Commuters jostle under an expansive sky, angling for standing room in the autumn sun. Today’s remarkable weather, however uncommon, evokes fabled histories of a famous Dutch light, heralded by renowned 17th century landscape painters.

century landscape painters. Journeying to Matloga’s studio by boat feels particularly appropriate. The NDSM site was once home to a mammoth shipbuilding company, closed for good in the mid-1980s. Taken over by squatters, the complex absorbed waves of artists and creative start-ups at the beginning of the new millennium. More recently, it has made way for the ever-encroaching glass and steel of corporate offices and luxury living. Some conventional industry remains though; beyond an immediate community of photographers, painters, installation artists and VR engineers, Matloga works directly beside a small-scale bicycle manufacturer, while ships are still meticulously repaired in adjacent warehouses.

The studio – where I am greeted with a detox tea – is a kind of box within a box; a rectangle in the belly of a hulking hangar. It is clad, from the outside, in a layer of translucent, pink bubble wrap, presumably to soften the sounds of fellow workers, and as an added layer of insulation. “It gets super cold here in the winter,” Matloga complains. Up the stairs via a spacious common area, we pay a brief visit to a neighbouring photo studio, where we are introduced to its operators’ projects. “Most of the time, we bump into each other in the kitchen. That’s where we connect, where we decide which exhibitions we want to go to,” he explains. “There’s definitely a sense of community.”

Mixing it up

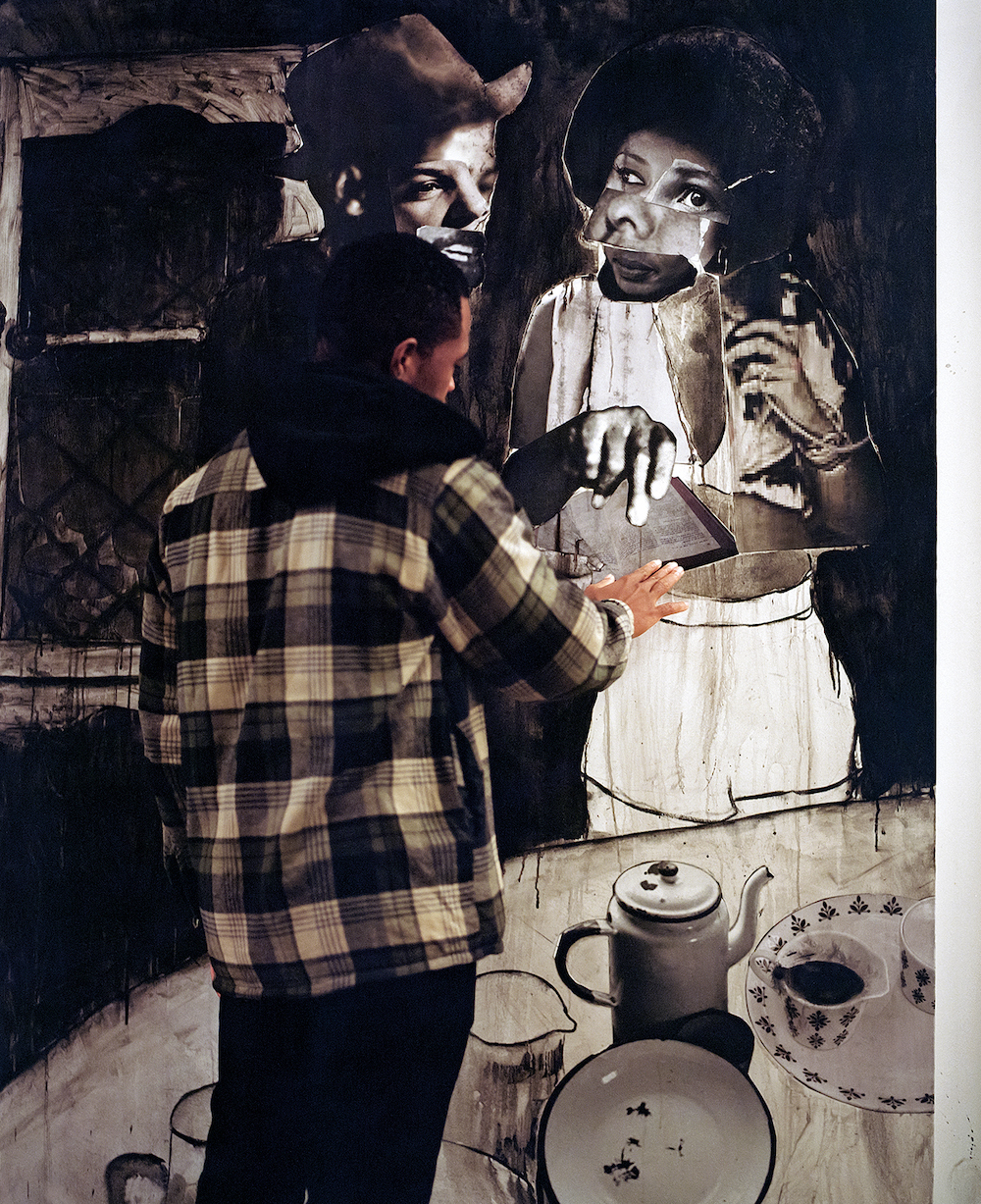

Hailing from South Africa, Matloga initially came to Amsterdam strictly to paint. But during a two-year stint at De Ateliers, an intensive postgraduate residency programme, he decided to switch mediums. “I felt like oil painting was something I needed to understand scientifically; it seemed too sophisticated,” he recalls. “I needed to resurrect a sense of rawness.” Experiments with charcoal line drawings followed, as did trials with ink, which offered his works a visceral fluidity. Both are combined with cut-out, collaged photographs – sourced primarily from magazines or newspapers, and printed with varying degrees of sharpness, contrast and opacity. “With painting, it wouldn’t make sense to render everything in the same way, so mixing it up gives some vibrations to the work. It makes these paintings beautiful ugly things!”

Matloga describes what his works depict as “socially confirmed scenes”: of everyday domestic life, Black joy, of people sharing a coffee, families listening to music, gossiping, dancing, of couples kissing or courting. Each work draws inspiration from a vast range of sources – be it the artist’s childhood memories, his dreams and travels, or perhaps another artwork, a newspaper article, a story or a recent conversation. The universality of these scenes is enhanced by Matloga’s application of photo collage. Gathering and reworking people from print publications, family albums, video stills and newspapers, the social status of his human subjects dissolves on canvas; hierarchies are flattened as the faces of friends, celebrities, family members and politicians merge.

“ With painting, it wouldn’t make sense to render everything in the same way, so mixing it up gives some vibrations to the work. It makes these paintings beautiful ugly things”

When discussing his practice, Matloga foregrounds the significance of formal elements – materiality, composition, structure. These same concerns shape his interests in the work of other artists, from the ‘painterly layers’ of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner to Lubaina Himid’s festive, theatre-inspired scenes: “I guess I tend to appreciate the work before going into the whys,” he muses. Like Himid, Matloga describes his working process as akin to staging a theatre piece: “You need some lighting, some props, a stage, a cast… it’s like putting all those theatrical elements together in a box.” Where many artists choose to work in splendid isolation, free from the weight of external references, Matloga exhibits an openness for creative exchange. Incidentally, the very pieces we see hanging in his studio – their protagonists’ eyes gazing back at us – are destined for a show in Antwerp, to be set in dialogue with works by the late Paula Rego.

The notion of home is another central aspect of Matloga’s work. The treasured objects that surround his characters are the kind of keepsakes “that make a house a home”. The artist lights up visibly at the mention of Limpopo, the South African province where his former family home has become a second studio – offering an escape from miserable Dutch winters. “I have goosebumps just talking about it,” he says, “because that’s where the spark is for my work.” In the time he spends there, a gentler rhythm takes over, while the dual obligations of family and village life become a direct source of inspiration; tight-knit communities are always a “good place for thinking about human behaviour”, a far cry from the lonely individualism of northern Europe.

During our exchanges, Matloga is notably hesitant to dissect his work’s politics – and it is easy to understand why. Portrayals of Blackness, however universal, are interpreted far too readily through this lens; in some way, Matloga’s work proffers a refreshing counter-image to many such charged narratives. But in his fixation on home, quiet political undertones do surface, without ever being floodlit. In the years of apartheid, and after its dissolution, any house was an invaluable safe space; a place of retreat from the turbulent world outside, where private dramas displaced broader social crises. “The home was where people could let loose and speak about literally everything,” he explains. “Whether it was the new political announcement on the radio or the latest gossip from down the street, home became the pulse of everything that was happening. To this day, it still is.”

The longer I spend at Matloga’s studio, the more I observe the finer details – distinguishing rigid brushstrokes from softer charcoal finger-markings. I ponder the inner worlds of his collaged characters, and realise that his palette, though restrained, is far from monochromatic. Shades of brown, stone and deep purple linger next to black and white. With photographs taken and artworks discussed, the visit concludes with a gossip of our own. We talk over tea and macarons, exchanging stories of art, work and life in the city. Later, Matloga’s record player whirs into life. It is a humble yet communal scene, befitting of the canvases looming over us.