Toni Frissell, WAAC (Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps) officers sitting under hair dryers, 1943, Vogue © Condé Nast

Condé Nast’s magazines were pioneering in their support of artists including Lee Miller, Irving Penn, Edward Steichen and Diane Arbus. What do their pictures of actors, politicians and writers tell us about how culture is constructed?

At a time when cultural taste is an individualised value, the idea of an absolute authority – or the perception of one – feels distant. For a time, Condé Nast’s Vogue and Vanity Fair occupied this position: the belief that a certain class of person, wielding the new influence of mass media, could decree merit and relevance across multiple aesthetic spheres. Ernest Hemingway, Twiggy, James Joyce, Karl Lagerfeld. All were photographed for Nast’s magazines, the pictures revealing the key paradox underpinning their existence in the 20th century. If composed in a certain way, the titles had the power to not just reflect the culture around them, but to shape its future. The almost impossible task, especially from such historical distance, is to gauge just how prescient their influence was.

Chronorama, a new exhibition of 407 photographs drawn from the Condé Nast archive, demonstrates the pioneering role Vogue and Vanity Fair played in documenting 20th-century culture, while also asserting Nast’s wider role in the public sphere. The magazines were a mirror that “does not simply reflect reality,” but “goes above and beyond and is so powerful that it ultimately distorts reality itself,” the curators say. A glamour and aestheticism whose most distinct quality was its unwavering belief in its own vision – lofty new media ideals combined with a distinctly American self-assurance. “Your magazine should cover the things people talk about,” future Vanity Fair editor Frank Crowninshield told Nast in 1913. “Parties, the arts, sports, theatre, humour, and so forth.” The idea was to ensure that people kept talking about these things, but through the tastes, social and commercial perspectives of Nast and his associates. A self-generating and self-fulfilling prophecy of cool.

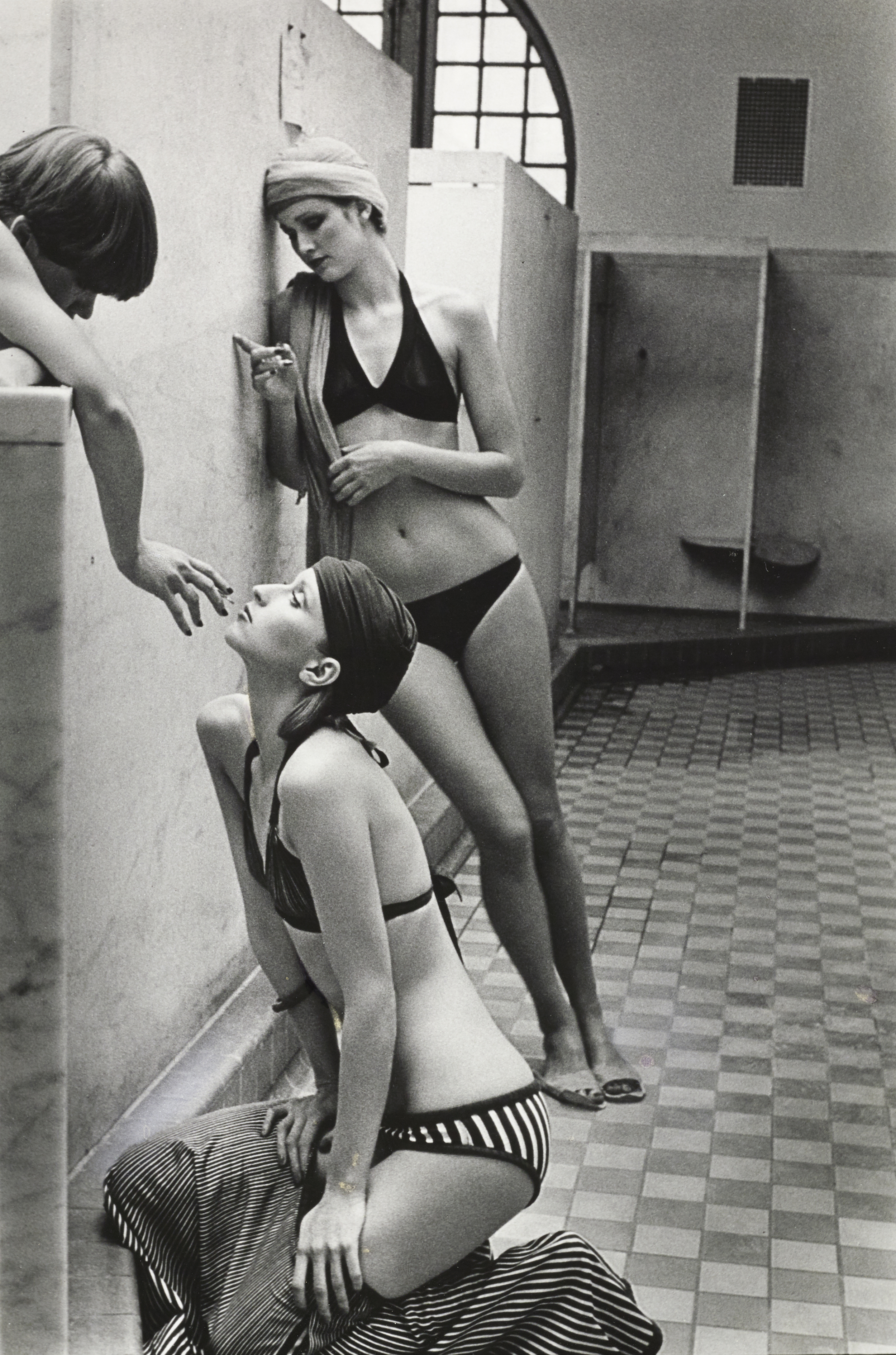

During the 20th century, photographs replaced illustrations as print’s primary visual vehicle. When Nast made Adolf de Meyer the main photographer for Vogue and Vanity Fair in 1913, pictures weren’t seen as an appropriate artform for magazine covers. And yet, Nast paid de Meyer $100 a week to shoot for what would now be called early fashion photography. His image of actor Ann Andrews gazing into a mirror while adjusting her hair speaks to self-consciousness the medium allowed – a new era of access, but also self-fashioning and image-control. By the 1970s, this had become what we now recognise as fashion shoot and editorial photography. Richard Avedon covering half his face for Irving Penn; David Hockney chomping a cigar for Helmut Newton. But also, Nast’s patronage encouraged new innovations in subject matter and concept. Penn led the way with his still lifes, alongside Peter Hujar and Bob Willoughby.

The exhibition traces celebrity culture through several guises. The perpetual glamour of actors and Hollywood, the zeitgeist-driven interest in activists and politicians, the calculated aloofness of authors, poets and designers. There remains a unique drama in asserting a person’s importance – the decision to elevate an individual above the rest which defines editorialisation. Time gives the portraits a classical feel – a romance which builds in allure with each passing year. Hans Namuth captures Jackson Pollock leaning over a canvas in splattered loafers, a bucket and paintbrush in hand. Charles de Gaulle looks stern as he poses for Cecil Beaton and Vogue in 1944. Penn’s pictures of Salvador Dalí and Gala, Le Corbusier, and Henri Cartier-Bresson feel gently ironic, the posing freedom adding to their gravity. In his portrait by David Bailey, it’s as if Mick Jagger is inventing the quizzical frontman glare from scratch.

Many of the photographs didn’t make it into Condé Nast magazines, and are being displayed for the first time. Others have been dragged from their editorial context and into the exhibition format, blurring the line between photojournalism and fine-art imagery. In reality, the line isn’t too important, because the work on show belongs to various photographic traditions. What matters is the cumulative effect – the way that presenting pictures chronologically (and in such high volume) encourages a kind of teleology. Recognising someone before they become famous; an innovation before it’s accepted into the mainstream; a person’s pride before their fall; a moment which transcends its era.

“There remains a unique drama in asserting a person’s importance – the decision to elevate an individual above the rest which defines editorialisation.”

Lee Miller’s Vogue photographs from Second World War France and Britain stop you in your tracks. Her Interrogation of a Frenchwoman who has had her head shaved for consorting with Germans is a monument of pure anguish and consequence. Penn’s portraits of John F. Kennedy are lent their status by the events which followed – time creating its own icons. Coco Chanel by George Hoyningen-Huene. Iggy Pop by Peter Hujar. Alfred Grabner’s Street Crowds foregrounding photography’s ability to capture crowds and with them, mass sentiment and emotion. Ezra Stollen’s 1966 image of the Whitney Museum and Marc Riboud’s of The Centre Pompidou showing the increasing value of industrial design and architecture in visual culture.

The latest image in Chronorama is from 1979. Two models look into each others’ eyes, the woman holding a bottle of perfume, the man looking slightly suspicious. It marks an artificial bookend – the end of a survey which creates its own narrative, a specific arc through time whose minor achievement is to disguise its own exclusivity. This is Nast’s world – a taxonomy of the Western cultural gaze with all the blindspots that entails. Tastemaking and cultural leadership as existential acts.

In a sea of black-and-white, flashes of brilliance stand out. Miller and Penn; Hujar, Beaton and Edward Steichen’s early genius. Most remarkable – and undeniably positive – is the creative and commercial support these magazines offered to photographers over such a long period. Today, when creating a unified theory of culture is no longer desirable or possible, Nast’s vision is unique. In service, perhaps, of values which no longer exist, but occasionally, and gratefully, producing groundbreaking results.

In a sea of black-and-white, flashes of brilliance stand out. Miller and Penn; Hujar, Beaton and Edward Steichen’s early genius. Most remarkable – and undeniably positive – is the creative and commercial support these magazines offered to photographers over such a long period. Today, when creating a unified theory of culture is no longer desirable or possible, Nast’s vision is unique. In service, perhaps, of values which no longer exist, but occasionally, and gratefully, producing groundbreaking results.

Chronorama: Photographic Treasures of the 20th Century is at Palazzo Grassi, Venice, until 7 January 2024