This article is printed in the latest issue of British Journal of Photography: Performance. Sign up for an 1854 subscription to receive it at your door.

Eli Durst, Jamie Lee Taete, Rik Moran, James Bannister, Alison Jackson and Ayesha Jones explore what truth – personal, political and even extraterrestrial – means in the context of their work

Since the 2016 US presidential election, we have been increasingly described as living in a post-truth world. In this era of alternative facts and fake news, of vaccine scepticism and climate change denial, the importance of the objective, verifiable fact has never been greater. But misinformation did not originate with the rise of Donald Trump. Propaganda far predates social media and, from the earliest cameras onwards, photographers have been questioning and experimenting with the medium’s connection to truth. The discussion of objectivity in image-making is nothing new, but in the post-truth age, is it taking on more significance?

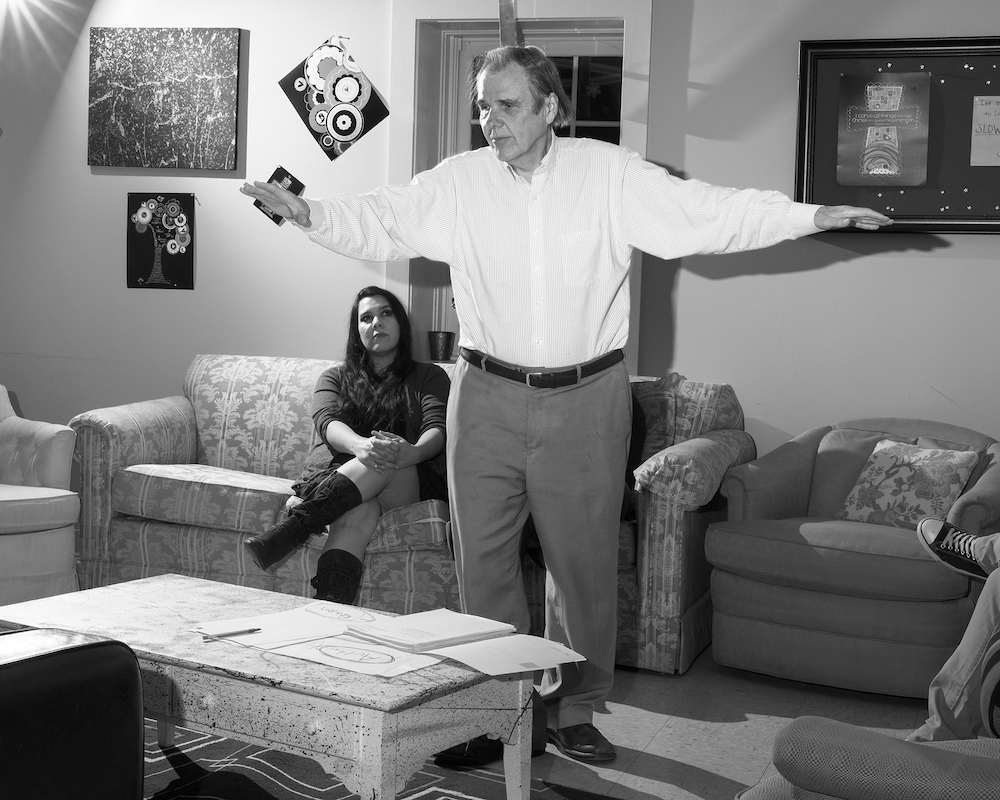

Eli Durst

“In this image, a man in a New Age class spins around in circles – much like a whirling dervish – in the hope of accessing a meditative state. He spins 33 times, in reference to the age of Christ when he was crucified. This photograph was made in a relatively straightforward documentary style. I observed the class and made photographs throughout, sometimes asking people to stop or repeat a certain action or exercise. In this way, the photograph is an honest document of reality, a description of the surface of the world at that moment, something we might call truth. In another way, however, the photograph is a cipher, a physical description of a metaphysical dimension, invisible to the camera. It is a photograph of this man’s faith, a spiritual experience from which the viewer is excluded, something very far from fact or objective truth.”

Jamie Lee Taete

“I took this at a Trump rally in Wyoming in 2021. I noticed the car because it had personalised number plates that read QP8RIOT, a reference to the QAnon conspiracy theory movement. The car’s side and back windows, and about two-thirds of the windscreen, were covered in stickers relating to the driver’s various conspiratorial beliefs: that Covid-19 vaccines are poisonous, that JFK Jr faked his own death, that a group of global elites are involved in a massive child-trafficking ring, and – I think – that Donald Trump is the reincarnation of General Patton. There are many ways that these types of conspiracies can be harmful to the believer. But it’s rare to see someone whose beliefs put them in such immediate danger – to such a degree that they are unable to safely operate their car.”

Rik Moran

“Truth is inherent in my book, Chance Encounters in the Valley of Lights. As a story about a story – of Alan Godfrey, a Todmorden policeman who claimed to be abducted by a UFO – it plays to the way we tell them. We emphasise, exaggerate and embellish in the name of a good tale. What truths lie in Godfrey’s story when there’s no evidence beyond his recollection? Growing up nearby, this story has lived with me for over 30 years. I wanted to tell my truths, presenting the facts for the viewer to draw their own conclusions. This image shows the Todmorden, West Yorkshire, landscape where Godfrey had his encounter. Shot on Aerochrome film, which records infrared light invisible to the naked eye, it reveals hidden truths within the landscape: a fitting metaphor for the untold stories present all around us.”

James Bannister

“Las Vegas projects a facade of success and glamour. It’s something that we all buy into. We train our vision to see what the casino-hotel owners want us to see, and are blind to what they don’t. We see the easy lie, not the difficult truth because the world is complicated, and this helps us digest it. Despite the dire water situation – a symptom of being only two hours from the hottest place on Earth – lawns, pools and golf courses have become a status symbol in Las Vegas. A signifier of our relationship with scarcity and value. An investigation into presentation, photography can sometimes have a great knack of getting under the cracks of the image we project. I find the distance between the fantasy and the reality of ourselves very revealing. Arbus called this ‘the gap between intention and effect’.”

Alison Jackson

“I started my MA at the RCA hating photography because of its manipulative qualities. I ended up making this whole body of work about exactly that – about how you can’t tell what’s real or fake through photography; you can’t rely on your own perception. My work bursts the bubble that we can believe in anything we see in an image, exploring how seductive imagery is, even when you know that you can’t believe it’s true. Photography is not truth – it’s only resemblance. In my work, resemblance becomes real and fantasy touches on the plausible. I create scenes that the public have all imagined, but have never seen before. It’s an exploration of our insatiable desire to get personal with public personalities, raising questions about the power of imagery, which incites voyeurism and our need to believe.”

Ayesha Jones

“As I sat to think about these words, a man asked me, ‘Where do you come from?’. He wanted to inform me, unprovoked, that ‘I have mixed race kids too, you know’, like me. This image is from a project titled Where do you come from?. It is a response to being constantly asked this question, as a Black/mixed heritage person living in the UK. It is about the social construct of race. I have made photographs during time spent in the Caribbean, Wales and West Africa. Places that my recent and distant ancestors would have called home. This image was taken in my late grandmother’s car, at the top of a hill in Machynlleth, Wales. In the mirror is the place where I feel most at home, a bench overlooking the view below, a view enjoyed by my late grandparents, late father and now my son and I.”