After publishing Father with Aperture and exhibitions at The National Portrait Gallery and Foam, the Armenian American photographer looks ahead to her shows in Berlin and at Recontres D’Arles

After publishing Father with Aperture and exhibitions at The National Portrait Gallery and Foam, the Armenian American photographer looks ahead to her shows in Berlin and at Recontres D’Arles

Condé Nast’s magazines were pioneering in their support of artists including Lee Miller, Irving Penn, Edward Steichen and Diane Arbus. What do their pictures of actors, politicians and writers tell us about how culture is constructed?

Last month, 23-year-old photographer Quil Lemons became Vanity Fair’s youngest cover photographer. Here, we take a deep dive into the process behind the shoot

“I had access to what felt like this secret world,” says Dafydd Jones, who has worked as a social photographer since the 1980s for publications such as Tatler, Vanity Fair, The New York Observer, The Sunday Telegraph, and The Times. “I was taking pictures of elites that nobody had seen before. It was Thatcher’s Britain, a period of celebration for those that had money. People described it as the ‘last hurrah’ of the upper classes.”

In 1981 he won a photography competition run by The Sunday Times magazine with a set of photographs of “Bright Young Things”, named after the earlier group of hard-partying aristocrats immortalised by novelist Evelyn Waugh and photographer Cecil Beaton. Tatler editor Tina Brown hired Jones off the back of it, commissioning him to photograph the Hunt Balls, society weddings, and debutante dances that were a mainstay of the upper-class publication. Now Jones has put together a collection of his work for Tatler from 1981-89, titled The Last Hurrah and currently on show at The Photographers’ Gallery and put out as a publication by Stanley Barker.

Nelli Palomäki, Justine Tjallinks, Denis Dailleux, Mark Seliger, Thomas Sauvin, Gilles Coulon, Mattia Zoppellaro and The Karma Milopp are all showing work in the Portrait(s) Photography Encounter – a festival devoted to pictures of people. Based in Vichy, France, the festival is now in its sixth year, and has been overseen this time by artistic director Fany Dupêchez.

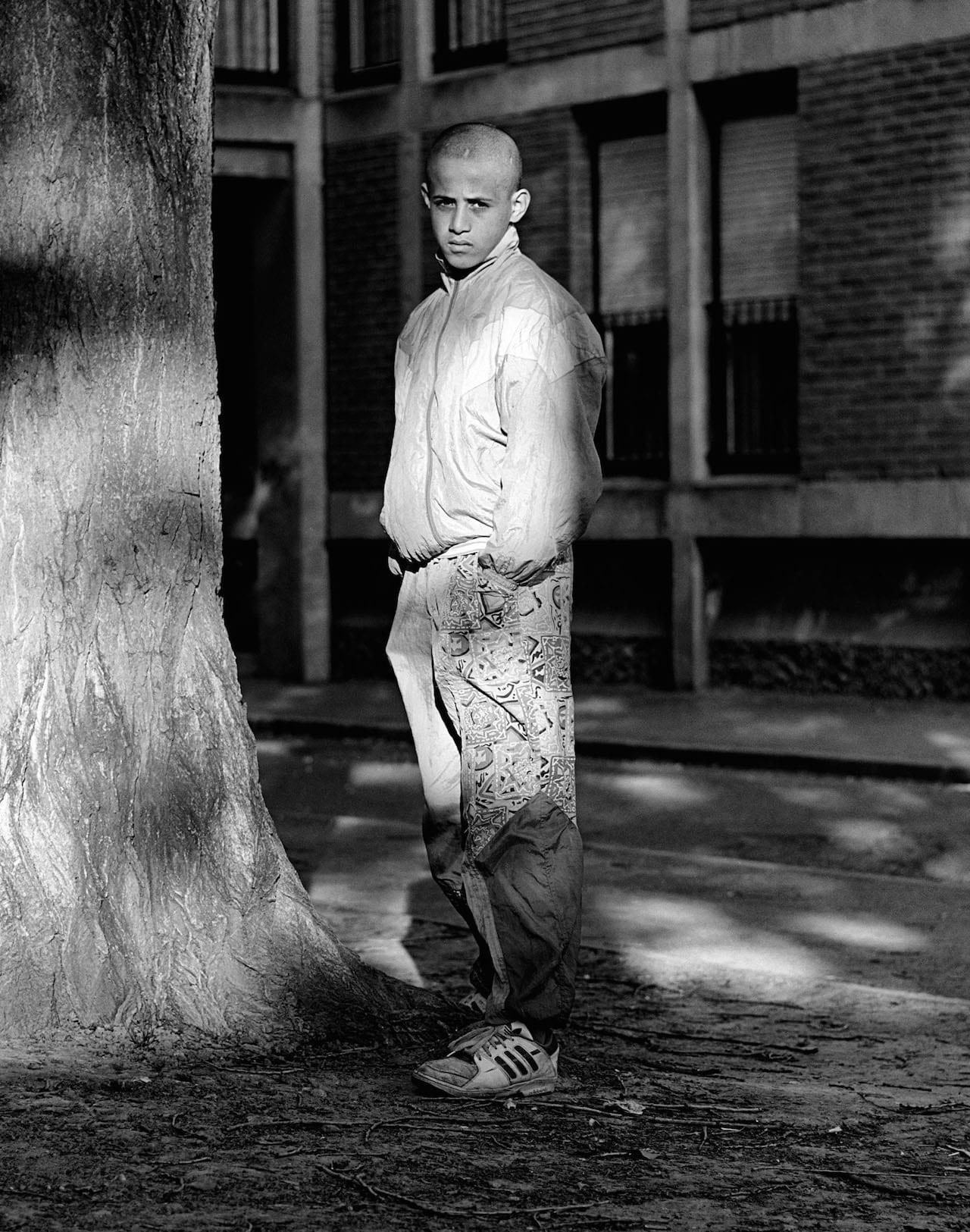

Dailleux’s images were shot from 1987-1992, and show children based in the working class suburbs of Persan-Beaumont, Northern France; the images Sauvin is showing are also from the archives, but were taken by amateurs in China, and rescued by the French artist after the negatives were sent to the Beijing Silvermine to be melted down.

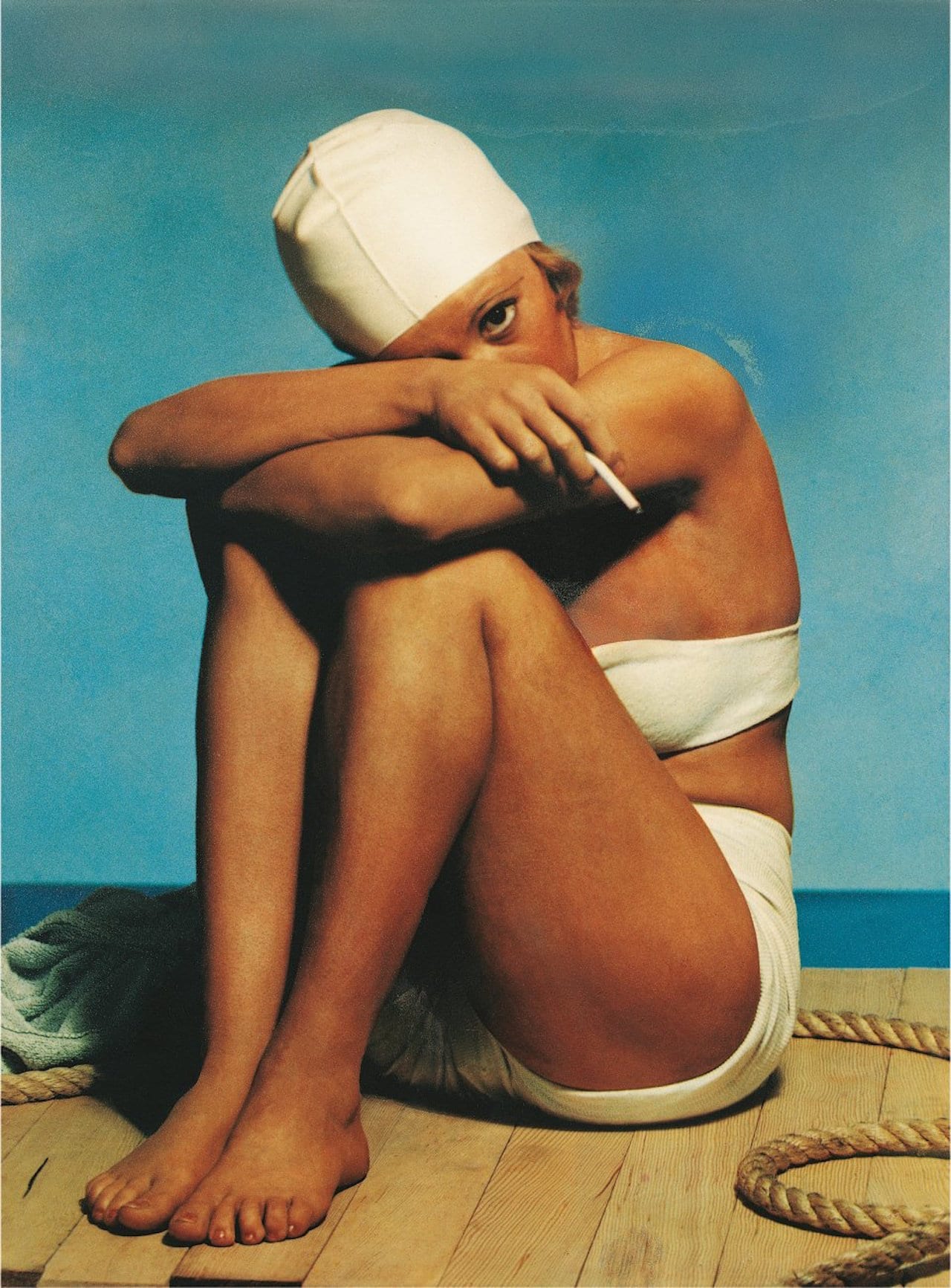

If you type “Paul Outerbridge” into a Google image search it doesn’t take long before work by other photographers turns up – images by contemporaries, such as Edward Weston, but also by successive generations of photographers who’ve been inspired by his work. The feminist Jo Ann Callis explicitly referenced Outerbridge’s nudes in her 1970s work, for example; in contemporary photography, the new wave of still life photography championed by image-makers such as Bobby Doherty and Grant Cornett references his work, especially his lurid use of colour. Outerbridge’s striking photography comes in and out of fashion, as it did in his own lifetime, but, nearly 100 years on, somehow still retains a contemporary edge.

“I always wanted to be a painter; I suppose most photographers secretly do,” says Erik Madigan Heck. “My mother was a painter. We painted together when I was a child, and she took me to the museum almost every week to look at paintings.” He’s gone on to develop a rich, painterly style of photography, which has brought him commissions from clients such as The New York Times Magazine, Vanity Fair, TIME, The New Yorker, and Harper’s Bazaar UK – and, most recently, with Sotheby’s Diamonds