Hands of God © Yashna Kaul

Yashna Kaul uses her father’s photographs to reconstruct his presence in her mind – years after his death from Alzheimer’s disease. The end goal isn’t truth, but the surreal wonder of family myth-making

Yashna Kaul was well on her way to completing a psychology degree at New York University when she took a photography class with Lorie Novak, the established American visual artist who works closely with family photographs. When Kaul returned to her hometown of Delhi in 2016, she discovered an extensive archive of family photographs, one that she estimates contains ten thousand pictures. Sifting through the images, she felt compelled to switch degree courses, completing her BFA in photography from NYU’s Tisch School of Arts in 2018.

For Kaul, discovering her family’s pictures was profoundly emotional. Her father, who took most of the photographs, passed away from Alzheimer’s disease when she was 16 and, since her parents were estranged, Kaul was not present during his illness. Working with the found imagery is Kaul’s way of reconstructing the memories they were never able to share. “I was reading a lot of blogs on Alzheimer’s [at the time of her father’s diagnosis] and I learnt that photographs helped people hold on to places and people,” the 27-year-old says. “That was my initial engagement with these images.”

Kaul’s experiments culminated in projects including The Image World, Hands of God and Sea is Rough, where collaging the photographs is the main technique. In November last year, works from the three series were selected by Bharat Sikka to be part of Nowhere is Home, a group exhibition at Photoink, New Delhi, which explored the delicate relationship between domestic space, family albums and nostalgia.

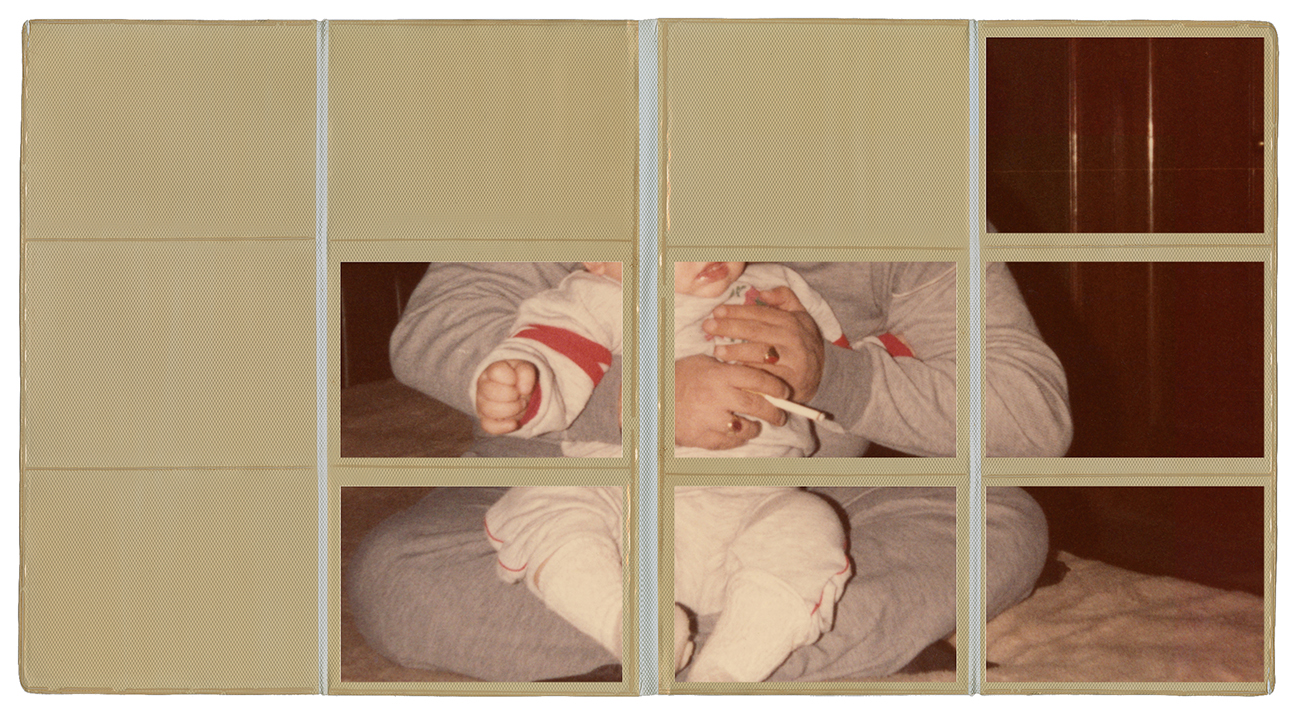

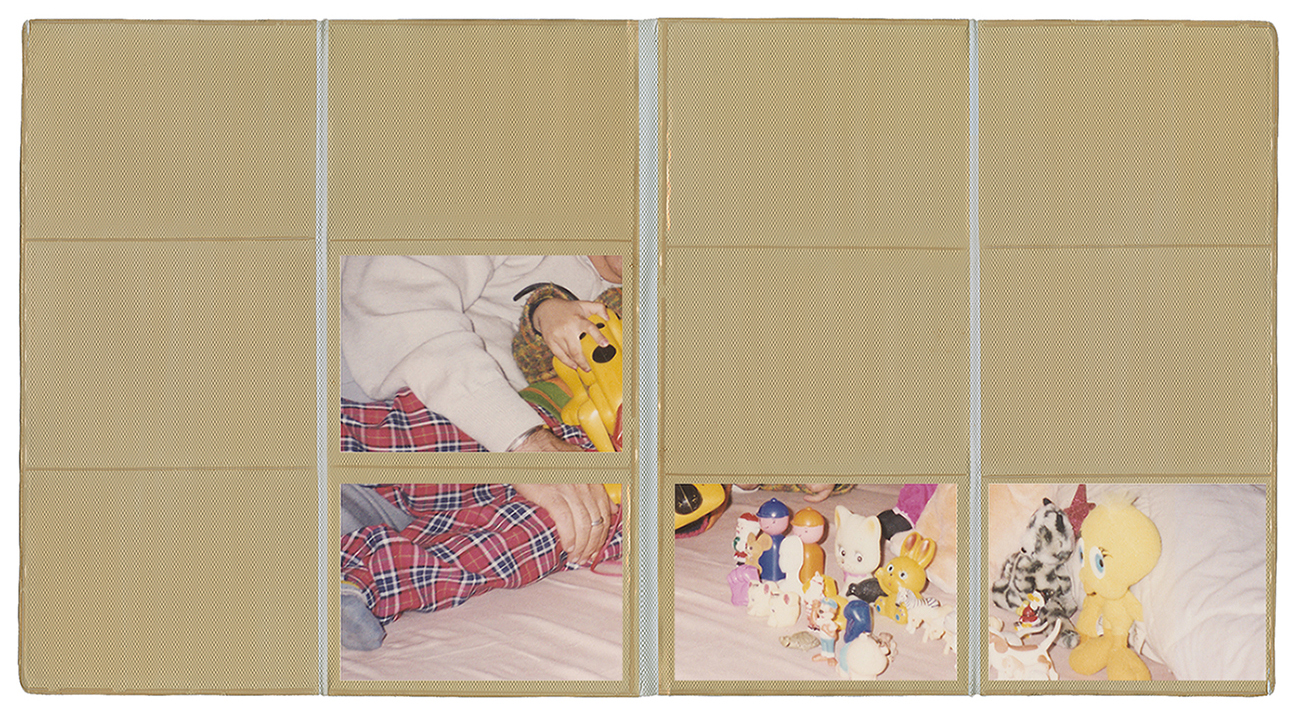

For Hands of God, Kaul created a photo album of images containing her father, enlarging them to focus on the details she can still remember. One of her clearest memories was her father’s deep belief in Vedic gemology, superstition and rituals. “I remember him coming home and removing all his chains and rings before he had a drink,” she recalls. Kaul searched for images where her father’s hands were visible, paying close attention to the rings he was wearing. The process of compiling this collection allowed Kaul to reconstruct his belief systems.

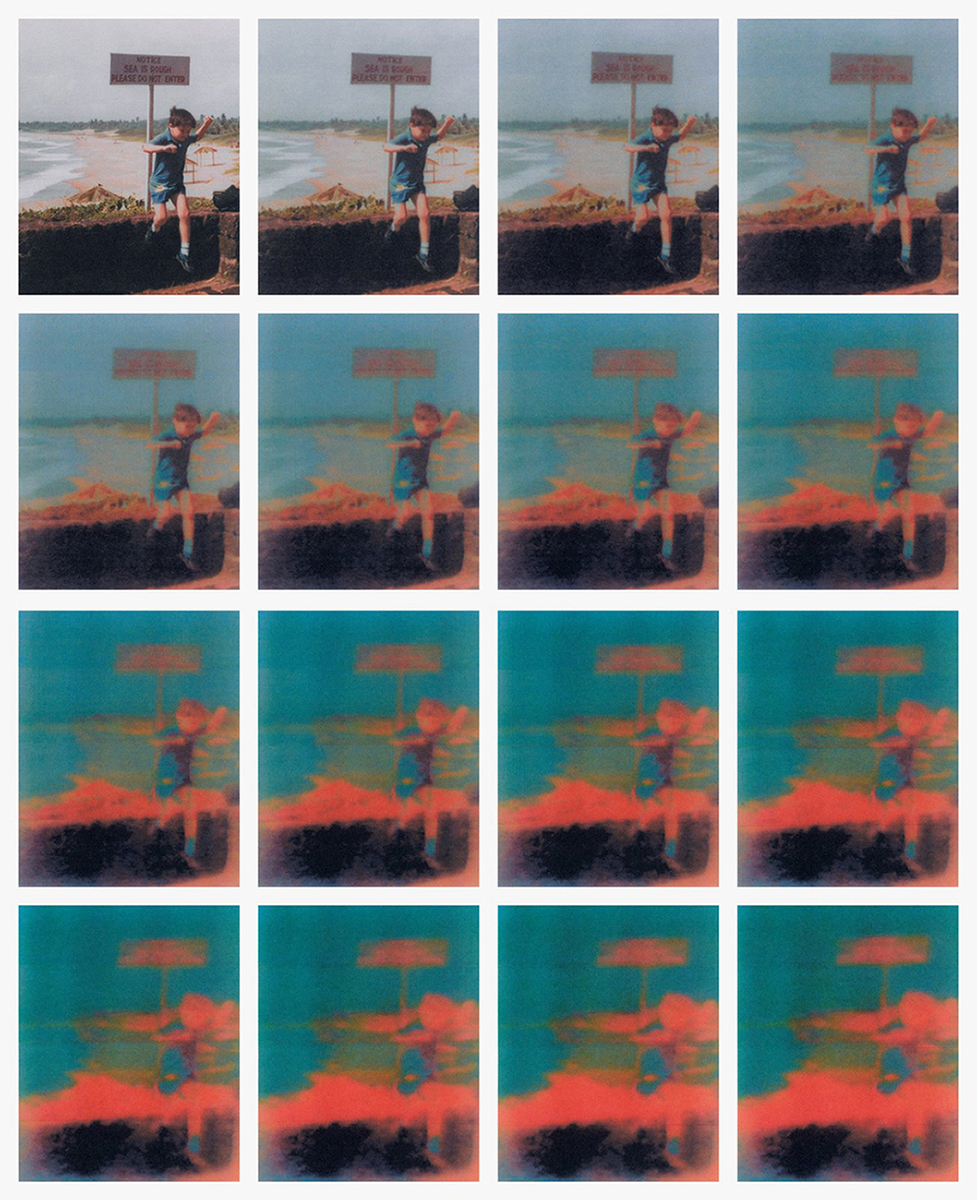

Sea is Rough is a set of photographs Kaul created using a technique she calls ‘generation loss’: the original image is scanned and copied, and every version is itself reproduced too. With each copy, details are lost in the process, leaving the end result distorted. These images reference the concept of memory recursion, the idea that when one remembers something, they are not recalling the memory itself, but rather the last time they remembered it.

Kaul’s obsession with memory – both the loss of it for her father and her need to (re)create it for herself – is evident across all her work. It creates a sense of yearning within the viewer, the desire to either insert themselves into the image of her idyllic family, or to play with their own recollections – contorting them to rescript their own stories.

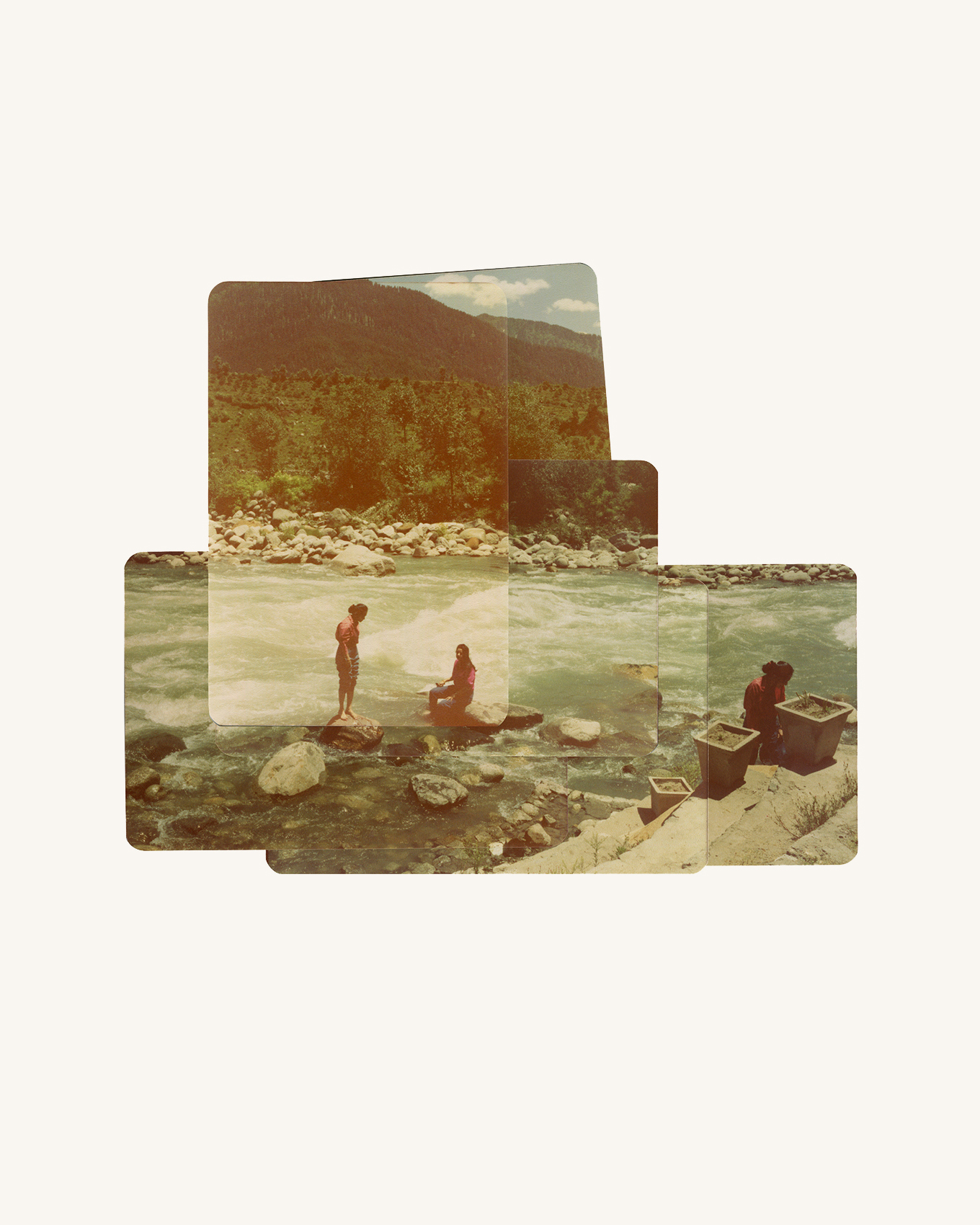

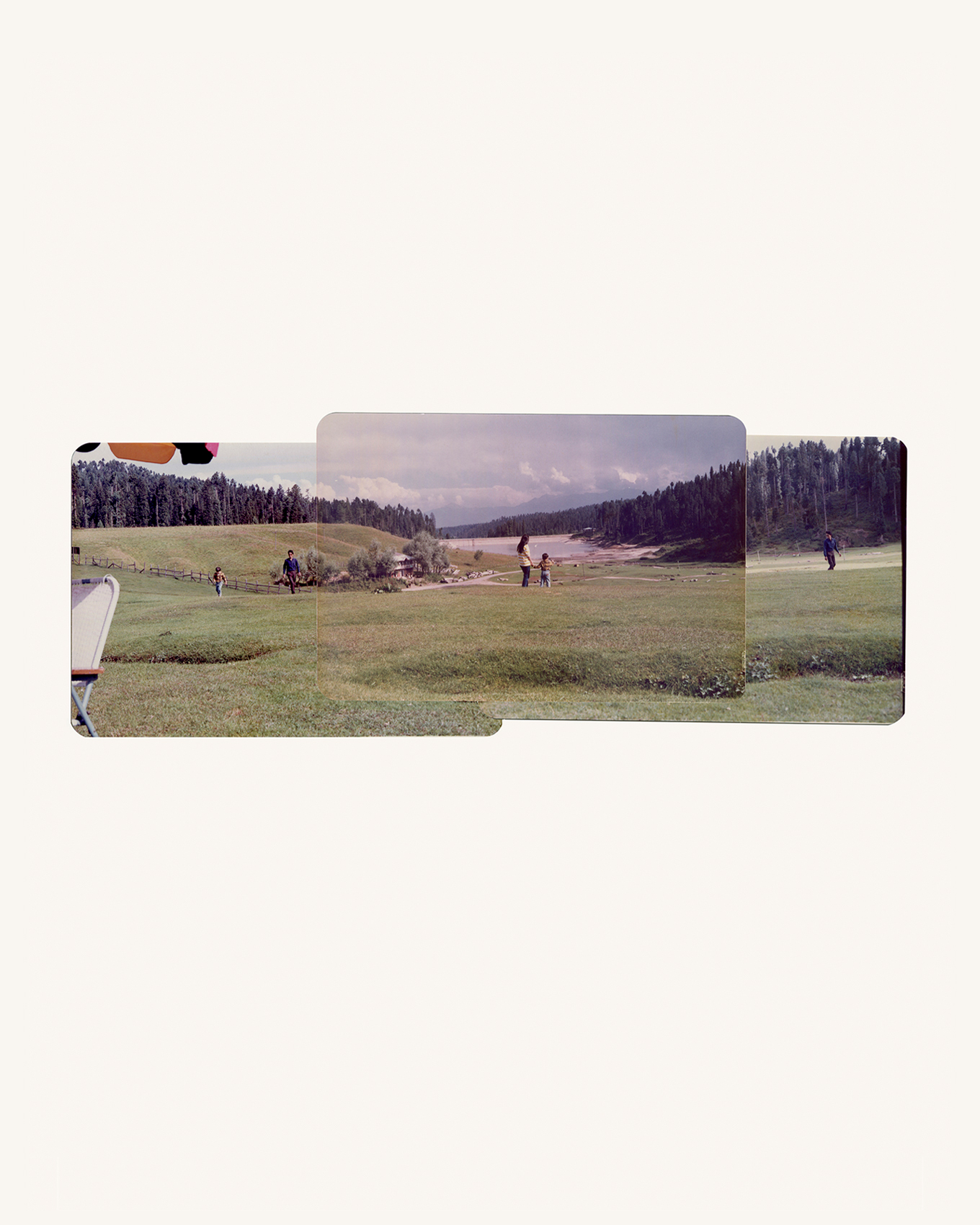

The Image World explores Kaul’s father’s affliction with early-onset Alzheimer’s. The majority of the photographs were taken during vacations between 1985 and 1990, when her parents and elder brother travelled to beautiful Indian towns like Manali, Srinagar and Pahalgam. Collaging these images became an important tool for Kaul. The ability to play with them, to move them around, is exactly how she imagined her father puzzling together pieces of their collective memories when composing the photographs. “I think he was quite reckless with how he took his images,” she says. “I would often find half a roll of film wasted on a single scene taken a few seconds apart.” Overlaying these images allows Kaul to extend these memories beyond a single frame and insert herself into these moments retrospectively.

While making the collages, Kaul realised she was viewing the photographs through the familial gaze. She encountered the concept in Marianne Hirsch’s book of the same name, whereby viewing family photographs becomes an exercise in retrospective idealisation – misremembering a perfect family which may not have existed. “It felt like [my parents] were creating these images with such an insistence,” Kaul tells me, “trying to capture the perfect family on film.”

“I was reading a lot of blogs on Alzheimer’s [at the time of her father’s diagnosis] and I learnt that photographs helped people hold on to places and people”

Kaul is now working on a book that takes a macroscopic look at all her family photographs, questioning the roles of fiction and myth-making. “Isolated images can transport me to a specific time or memory, but looking at them as a larger project will allow me to interrogate how these images narrate a fantastical or surrealist narrative,” she says.

She is also now avidly photographing her family, in the hope of building up her own archive. And although her interest in found photography continues to grow, she is certain that she doesn’t want to work exclusively with other people’s memories – just her own.

Yashna Kaul is at Photoink’s booth at India Art Fair, New Delhi, from 9 until 12 February