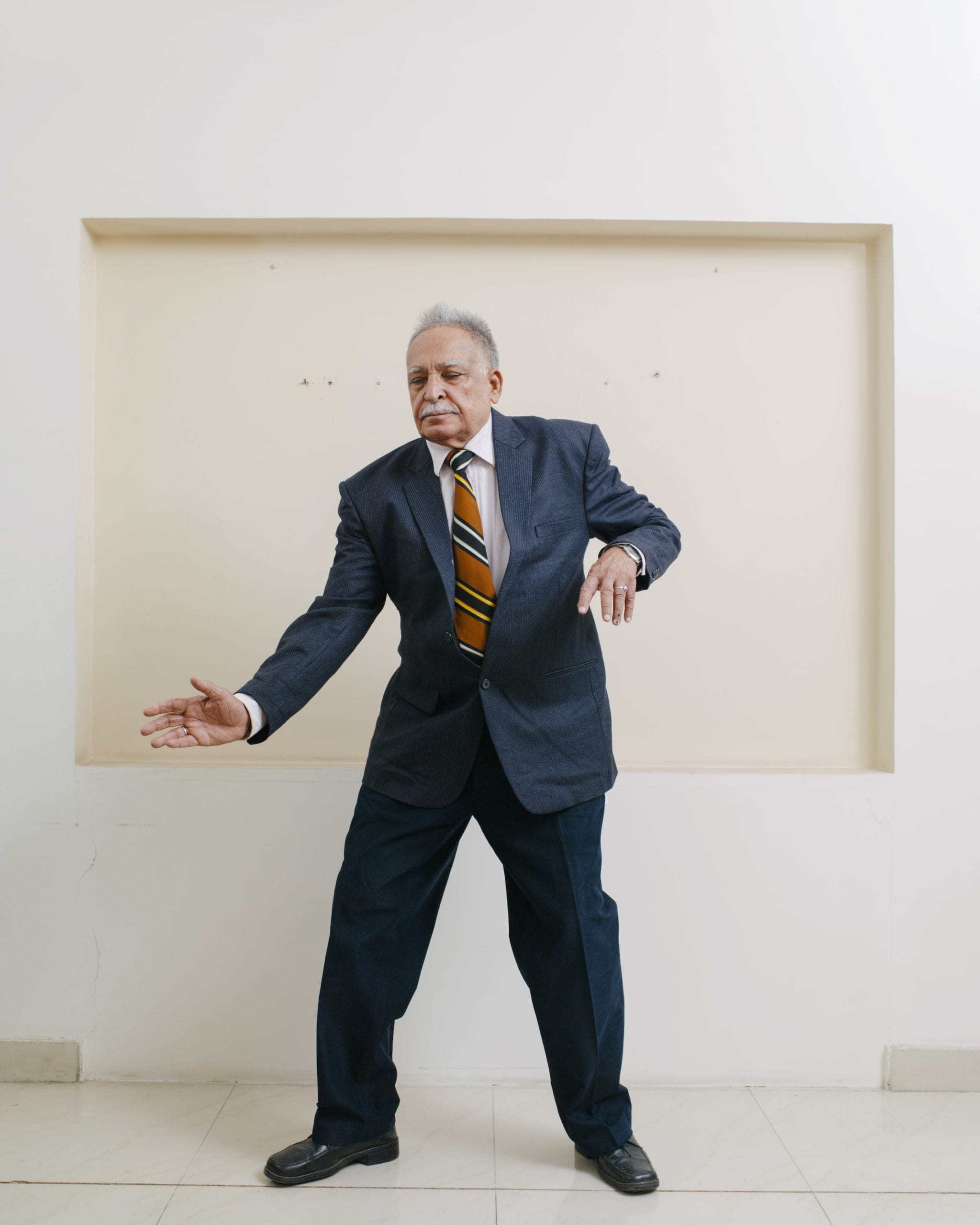

“Somewhere I realised I didn’t want to make a documentary-style project on my father, just photographing and capturing him,” he says. “For my first project [Indian Men], I photographed a lot of middle-class Indian men, and I included a lot of photographs of him. This time I wanted it to be much more playful, to break the rules a bit. It was about involving him in those things where we could do something more.

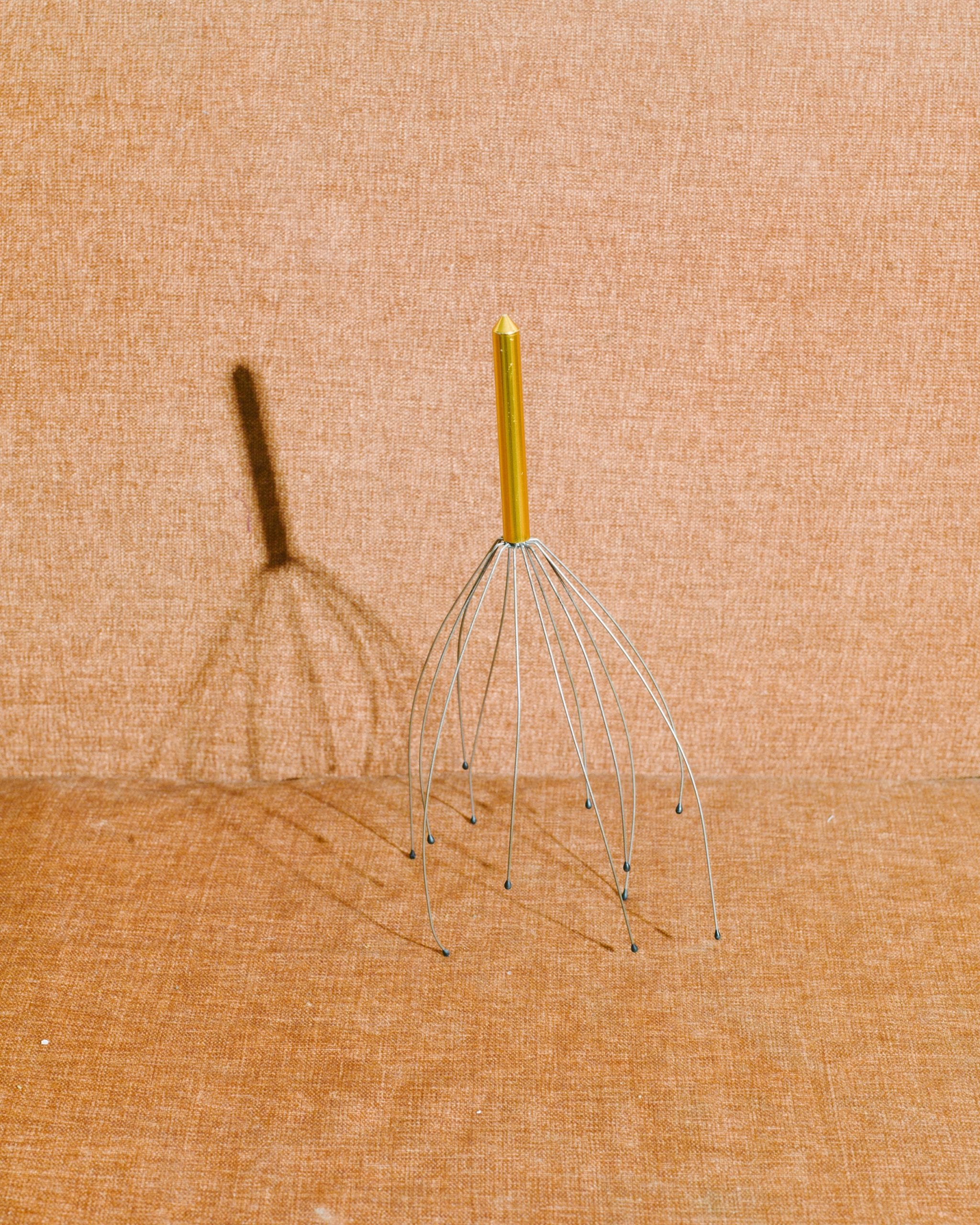

“My father had no connection to art but he’s a really creative person,” Sikka continues. “When I was growing up he would tell me what are the weak points of a bridge, how do you bring it down or make it stay up, and he would make these little sculptures with wooden pieces, tell me how to balance them and play with that. He was also a draughtsman, making these very linear drawings, and I wanted to include them by making the collages. We just played, we added another layer to this whole experience of doing the project.”

And that experience wasn’t just making the project. Sikka and his father worked on The Sapper in four locations – at home in New Delhi, in a house by the sea in Goa, in another house in north-eastern India near Darjeeling, and in Leh, Ladakh, which borders China and where Suresh was frequently posted for his work. And these trips were part of the adventure. “Leh is at really high altitude, and it’s a sketchy place [owing to border disputes],” says Sikka. “My father was 79 when we went there, so I was really scared. But he was fitter than I was.”

When Sikka showed a selection of the work at Unseen Amsterdam last year with his gallery, Nature Morte, his father came along. “He loved the adventure,” Sikka laughs. “There were so many different things that just came up as fun. Just imagine, your kid is older and he wants to spend time with you, you’re going to be really flattered. And it was interesting in our relationship because I would make him remember things and he’d tell me about his life, or we’d discuss some philosophy, or just do some origami.”

Sikka says he respects his father and avoided making images that would portray him negatively in any way. He adds that this respect is mutual, with Suresh happy to take direction from his son. For Sikka this was rewarding on a personal level, helping him get to know his father as an adult, but it was also an important part of the work. He’s keen to make images that fight back against stereotypes of India, from the outsiders’ idea that everyone lives in slums to the homegrown kitsch of Bollywood, and subverting the cliché of the strict Indian parent was part of it this time. “I wanted to show an Indian man in a different way,” he says. “Not go back to this really hierarchical world.”