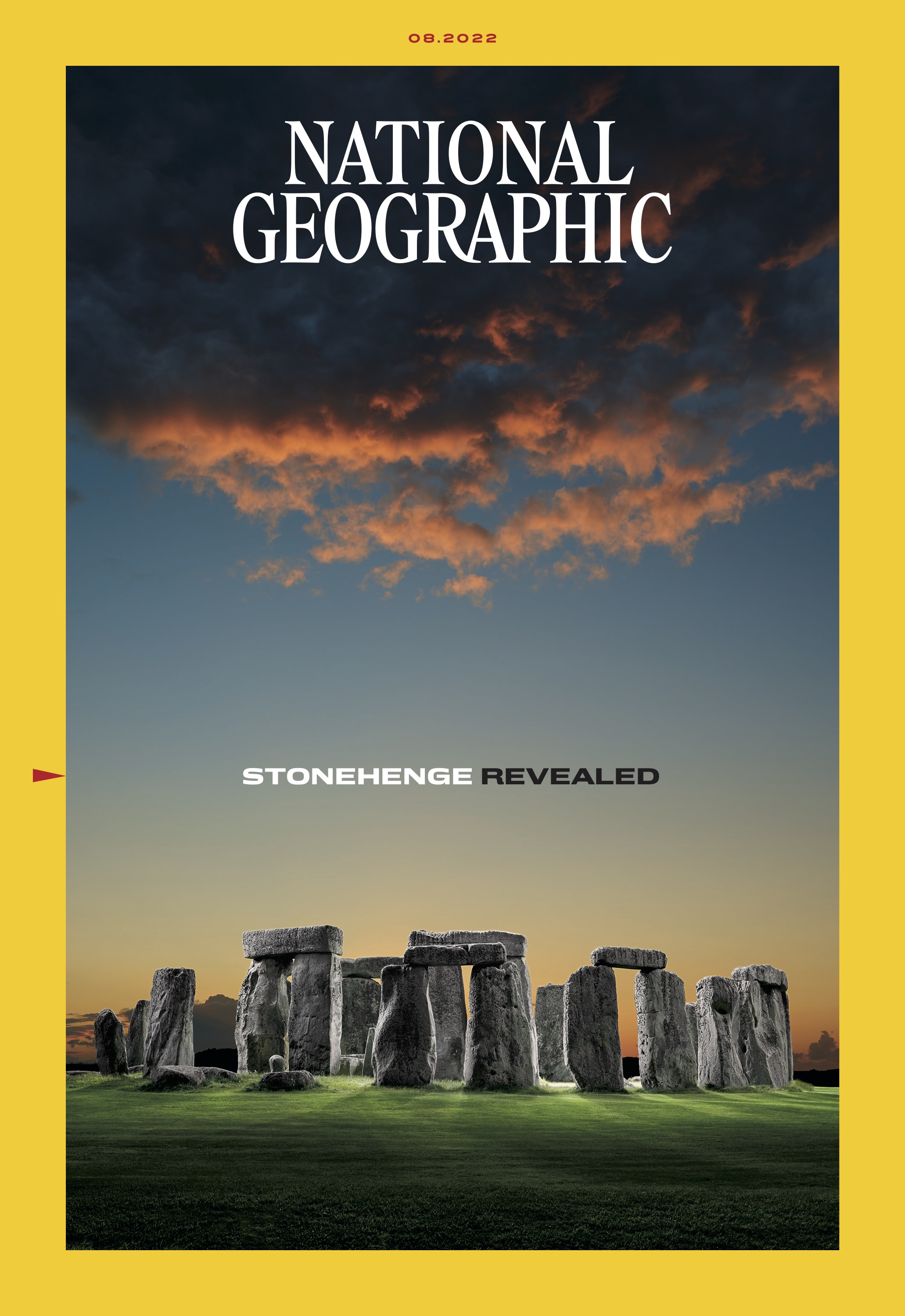

Behind the Cover: Reuben Wu and Alice Zoo on photographing Stonehenge for National Geographic

Cover of National Geographic's August issue, shot by Reuben Wu.

Source:

Stonehenge visitor Hanna Lingard greets the sun as a chilly dawn breaks on the morning of the autumn equinox. To protect the fabled monument from damage, most visitors are not allowed near the stones. But solstice and equinox are open-house occasions, and celebrants relish the opportunity to venture inside the stone circle. (Alice Zoo/National Geographic)

Source:Stonehenge’s uprights bear witness to the long march of time and visitors. Stone 60 appears to melt over a concrete filling installed in 1959 to stabilize the upright. (Alice Zoo/National Geographic)

Source:Sunset brings peace but not quiet to Stonehenge, which is bordered by a busy highway. “One thing that was jarring, even at night, was the constant noise of nearby traffic,” says photographer Reuben Wu. “I found myself imagining how the place would have felt thousands of years ago.” (Reuben Wu/National Geographic; image made with 13 layered exposures)

Source:A sprawling ceremonial complex in its day, Stanton Drew boasted timber circles, two avenues of standing stones leading to the nearby River Chew, and one of the largest stone rings in Britain, some 370 feet in diameter. Today 26 stones remain, and ground-penetrating radar has revealed nine rings of timber posts. (Reuben Wu/National Geographic; image made with 18 layered exposures)

Source:The autumn equinox brings a folk-festival vibe to Stonehenge as hundreds of visitors gather below its broad-shouldered trilithons. Aligned on the axis of the summer solstice sunrise and the winter solstice sunset, the prehistoric stone circle has long been a place of seasonal celebrations. (Alice Zoo/National Geographic)

Source:© 2022 - 1854 MEDIA LTD