Gap in the Hedge © Dan Wood.

This article is printed in the latest issue of British Journal of Photography magazine: Tradition & Identity. Available to purchase at thebjpshop.com.

Over the past two decades the social landscape of Britain has shifted with many provincial regions facing economic hardship and a loss of belonging. It is these places – where Brexit resonated – that many photographers with an affinity to the area are now turning their lens

Dan Wood grew up in Bridgend, a small Welsh market town 20 miles west of Cardiff. The photographer fondly recalls the boom times for the community, before the pit closures of the 1980s. Inhabitants of coal-mining villages further north in the Ogmore Valley descended in busloads to Bridgend’s cafes and shops.

“On a Friday or Saturday you couldn’t move,” he recalls. “There were people everywhere. It’s such a contrast to what it’s like these days.” The Bridgend of today is the subject of a trio of books by Wood, sometimes referred to as ‘The Bridgend Trilogy’: Suicide Machine (2016), Gap in the Hedge (2018) and Black Was the River, You See (2021). These publications – with their combination of documentary, landscape and portrait – typify a range of contemporary British practices exploring the relationship between people and place in smaller communities.

Often these are financially poorer, regional towns where the siren song of Brexit rang loudest, and where labels of right and wrong are tricky to assign. Towns like Bridgend, where the Leave vote was 54.6 per cent, are often subject to a metropolitan classist disdain. They are left behind by changing economic patterns, frequently causing problematic nativist politics to take root. The artists recording these communities – many of whom, like Wood, possess a strong biographical and emotional connection to their subject – are taking on an important ethical as well as aesthetic responsibility in depicting contemporary Britain.

These photographs are a contrast to the late 20th-century urban documentary tradition, represented by practitioners such as Chris Killip. His 1988 series In Flagrante brought to searing life the realities of industrial decline in Tyneside, northern England. The painful process of deindustrialisation in Britain’s urban centres – many of them now the subject of cosmetic uplift, particularly in the north – is arguably of less moral and artistic relevance today than it was 30 years ago.

It is the smaller, more remote centres – whose fall from economic stability was slower, less precipitous, less fought over – where the soul of Britain’s constituent nations is now being contested. Market towns that once relied on a flow of commerce from larger urban neighbours; pockets of lower-income life hidden in rural areas with high average living standards. These are now the sites of choice, or compulsion, for a range of lens-based artists. For Wood, there is a certain post- 2010, small-town malaise that is “the same everywhere”. “My wife’s from Chorley in Lancashire, and the general vibe of the place is exactly like Bridgend. There’s shops closed down, there’s people sitting on benches drinking cider. Everyone’s in the same boat with austerity and the cost-of-living crisis.”

Communities that have struggled to adapt to this new reality are the root of Wood’s interest, as well as what he openly calls “the grotty ends of town”. Both of these subjects reflect his background as a skateboarder: “We’d always find ourselves round the back of buildings, down alleyways… being a skateboarder, I’m drawn to a certain type of person.”

Wood’s Bridgend publications reflect his sense of kinship with perceived outsiders, who are often the subjects of his arrestingly intense but never exploitative portraits. These are interspersed with snaps of melancholy suburbs, scrap heaps, and lines of buildings cutting forlornly into woods and mountains. The combination captures the spirit of a place in transition without a clear destination.

There is a romantic, almost gothic touch to some of Wood’s images, where the familiar is overlaid with a sense of the exotic or remote. The artist is a fan of what he calls “Americana”. Many of his subjects seem to have taken on the persona of backwoodsman, cowboy or motorcycle rebel. Sports cars growing moss, a man on horseback at the end of a suburban terrace, a Route 66 sticker peeling off an abandoned fridge: these are among the detritus that points to this strange intercultural association – markers, perhaps, of a place formerly bound by a shared economic identity, where people are now looking for their own, more eccentric sense of belonging.

“If you ask people to describe a working-class person, they’re probably not going to describe a rural working-class person”

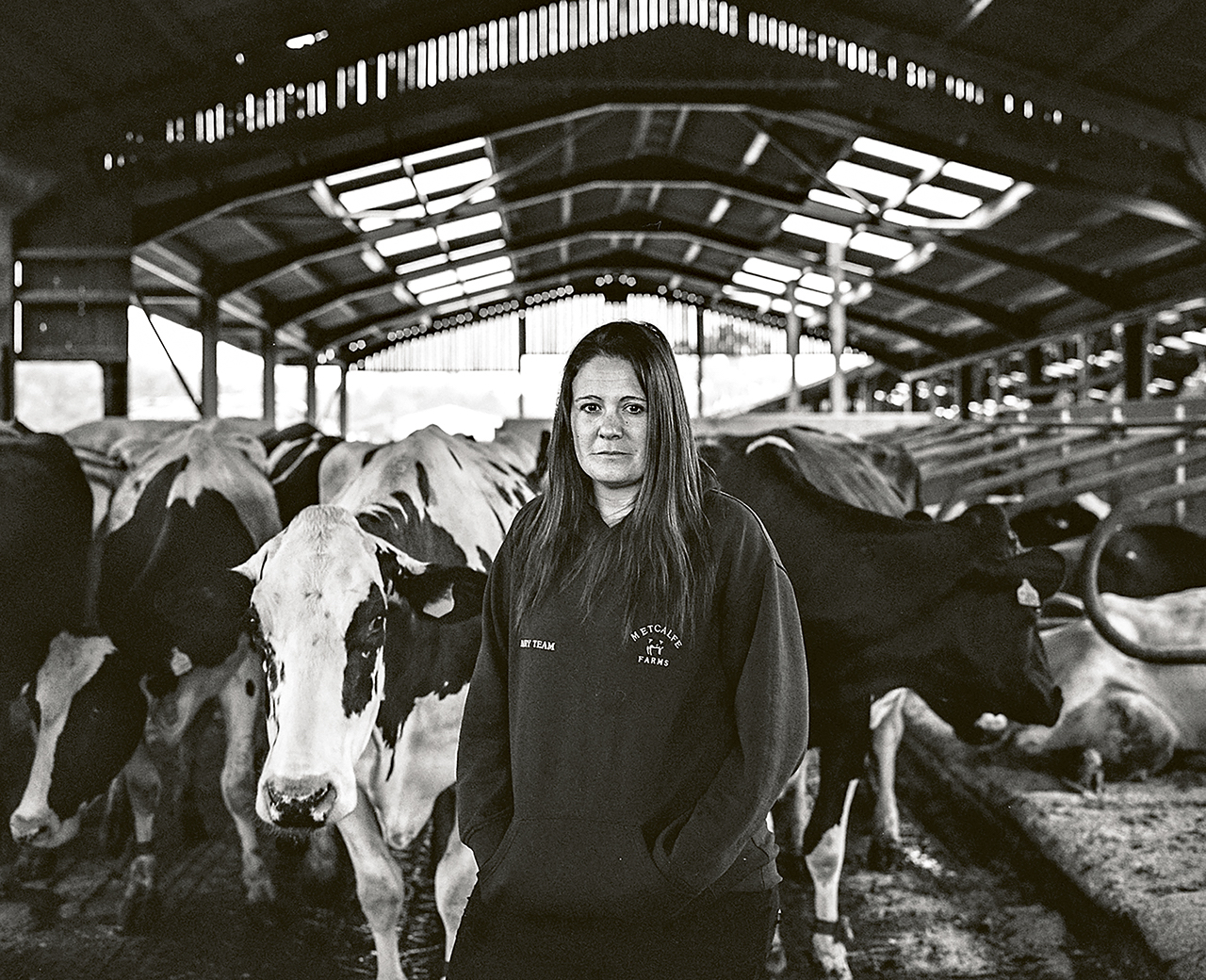

Joanne Coates

Championing visibility

Having grown up in a “rural working-class” family in Yorkshire, Joanne Coates also trained her lens on remote communities. For her ongoing project, Lie of the Land, which was awarded the 2021 Jerwood/Photoworks Award, Coates travels around rural north-east England interacting with women working in agriculture who identify as working class. These women, Coates suggests, are characterised by a philosophy of “graft” and a resistance to casting themselves as victims of an economic system, “even though they’re on a really low income, or they’re struggling, or they have multiple jobs”.

A key theme in Coates’ work is the invisibility of poverty in rural Britain. “You’ll come across villages that look really nice, but the council houses are hidden in a little cul-de-sac because they don’t fit in,” she says. “If you ask people to describe a working-class person, they’re probably not going to describe a rural working-class person.”

Like Wood’s photographs, Coates’ images convey a sense of easy intimacy with her sitters. But they offer a different, more unambiguous elevation of their subjects. “I chat to people and record the audio and then I’ll go back to them and say, ‘It would be really nice to have a portrait here or there’ – places that are significant to them,” she explains.

This emphasis on photographing people in settings that give their life meaning – providing a routine, friendship, self-worth – grants all of Coates’ images a quality of dignity and hopefulness that resists clichés. This shines through in her current touring exhibition Daughters of the Soil, which also focuses on women in agriculture. A sense of identity enmeshed with landscape emanates from these shots of women tending to livestock, resting on fences, or looking out across rolling, tree-speckled fields.

“I’m not interested in photographing the wilderness. If I look at a landscape I always want to know who works there”

Tessa Bunney

Adapting to change

Tessa Bunney grew up in the countryside too – in Somerset – and, despite spells working all over the world, she has continually returned to remote parts of her home country. “I’ve spent time in cities but I don’t really like taking photos there,” she says. But the pull of the periphery is not to do with escaping human beings: “I’m not interested in photographing the wilderness. If I look at a landscape I always want to know who works there.” In FarmerFlorist (2018), for example, Bunney captures the surprising development of a new type of British flower farming. This new paradigm, which developed in recent years, involves small teams of artisan growers producing huge varieties of blooms for local and national sale.

Britain’s older model for flower-growing involved heavy cultivation of a minimal amount of flower types. This became a redundant practice in the 1980s because, as Bunney puts it, “you could suddenly buy-in flowers cheaply from anywhere in the world”. Bunney presents a story about the resurgence of small-scale agriculture in an age dominated by global corporations

Like Coates and Wood, Bunney is interested in how communities in rural locations are dealing with shifting or unstable economic conditions. But she’s more focused on the detail, with images often homing in on the tools or products of a trade. “For FarmerFlorist I made a big grid of all the different types of flowers that were being grown across England. But it wasn’t about the flowers really, it was about recording the changing nature of flower-growing.” These close-up shots are brought to life by the human narratives implicit within them.

“I’m trying to provide a level playing field, so that photographers from any background and level of experience can have the opportunity to be published”

Iain Sarjeant, Another Place Press

Bunney is among a raft of contemporary photographers – including Coates and Wood – whose work has been published by Iain Sarjeant’s Another Place Press. Born in Kent but based in the Scottish Highlands from early childhood, Sarjeant is a self-taught photographer, graphic designer and publisher, who formed the publishing imprint around seven years ago to “try to make photography and photobooks as accessible and affordable as possible”.

In his description of the publisher’s economic model, there is a clear solidarity with the lower-income communities that binds together much of his stable of artists. “I want to try to make it accessible, both in terms of who can afford to buy the books and in terms of who can be published,” he says. Books are generally priced at no more than £20, the artist pays nothing towards production costs, and they receive royalties on every copy sold. “I’m trying to provide a level playing field, so that photographers from any background and level of experience can have the opportunity to be published.”

The practices explored in this article do not represent an authoritative overview of photographic work exploring regional and rural British identity. However, they are among those seeking to document a fresh vision of Britain in the early 2020s: a time in which paradigms of class, wealth and identity are being redefined in ways that are not yet fully formed.

This is a Britain always described, often slandered, and frequently cited as evidence for various theories of social renewal. But it is also a Britain that is rarely seen. Photography has a crucial role to play in this dilemma. It can capture complexity where prose may make knee-jerk judgements – particularly when the artist in question comes from a community similar to those they are documenting. Admittedly, the camera always carries hidden symbols, but it can also foster empathy and a sense of connection across boundaries of class, politics and place. This is what documentary photography, at its best, is capable of: forging a bond based on the humanity we all hold in common.