This article is printed in the latest issue of British Journal of Photography magazine: Ones to Watch, available to buy at thebjpshop.com.

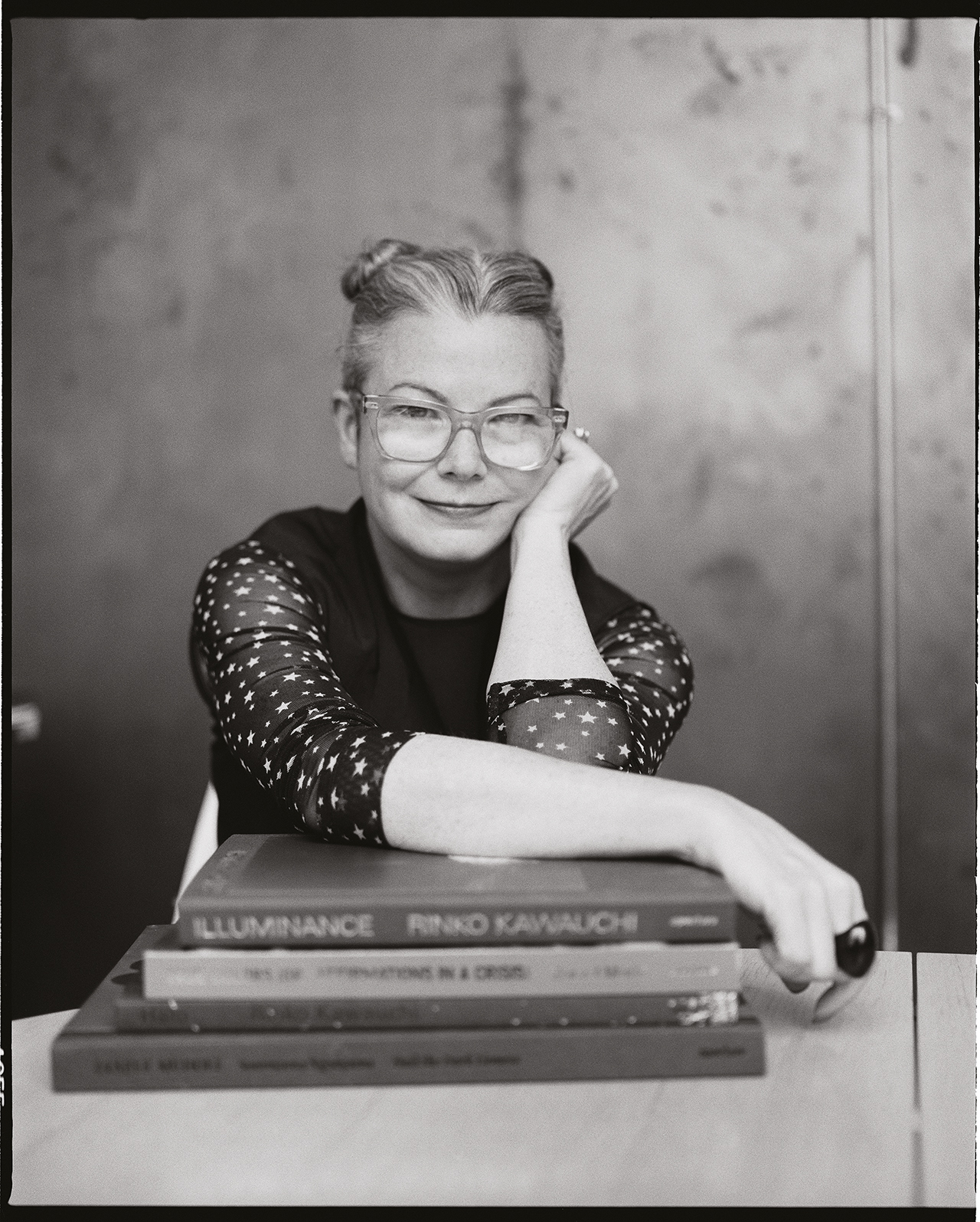

Since starting out as an intern 25 years ago, Aperture foundation’s creative director Lesley A Martin has edited scores of photobooks, including cultural touchstones by artists like Rinko Kawauchi, LaToya Ruby Frazier and Antwaun Sargent

Lesley A Martin began her career at Aperture as an intern, 25 years ago. Now the foundation’s creative director, she has edited scores of photobooks, including cultural touchstones such as On the Beach by Richard Misrach, Illuminance by Rinko Kawauchi, The Notion of Family by LaToya Ruby Frazier, Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness by Zanele Muholi and The New Black Vanguard by Antwaun Sargent.

Martin’s practice is dedicated to evolving the critical and creative dialogue surrounding the photobook. In 2011 she founded The PhotoBook Review, a biannual newsprint dedicated to the appreciation of the photobook, and in 2012 she co-founded the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards.

Here, she reflects on her life, career trajectory, and the evolving discourse surrounding the photobook.

Cultural complexity and the need for an expansive worldview were baked into the day-to-day of my childhood. I grew up overseas and attended school with kids from all over the world. My parents gave me the gift of an international perspective on the world.

My dad once told me to do the hardest things first. The stuff you really don’t want to do at all, get it out of the way. Start your day there. I’m not always good about following that advice.

I like photography where it feels as if something is at stake. I’ve always loved the idea that photographs contain secrets. The idea that images can be powerful or even dangerous has fascinated me for as long as I can remember.

I’m not sure that what I do is defined by ‘big breaks’. As a behind-the-scenes art worker, it’s about the slow and steady accumulation of experience and committed collaborative hard work. Getting the internship at Aperture was critical to who I am and what I do now.

Despite its share of difficulties, New York is amazing. The city has not yet returned to the full-throttle momentum it had pre-pandemic, but it’s still incredibly stimulating and inspiring with odd little happenings that you just stumble into.

There are so many challenges for photobook-makers today. Some of them are very familiar and somewhat basic, like how to raise the money and how to get books out into the world.

Other challenges are more directly linked and responsive to issues that have become progressively critical in the past few years. How to work towards a community that is more inclusive at all levels, for example, or how to deal with the terrible impact of the paper and printing industries on climate change.

The industry is becoming more decentralised while becoming increasingly networked online. Without engaged makers and audiences in smaller communities, it’s a very thin and narrow field. Review groups and darkroom shares, local zine makers and Risograph printers, book festival and workshop hosts, crit groups and book clubs – we need all of these to make up a healthy ecosystem.

I believe in self-publishing as a creative, artistic practice, but publishing is also fundamentally transactional. You make something for someone – for an imagined reader and audience. I think it’s a mistake not to try to put yourself in the place of someone who chances upon your book without any prior knowledge of you or the images.

The digital context of viewing can be stimulating and incredibly informative. But personally I find it less intimate and more about the speed of consumption and exchange. I like being able to go at my own pace, spending time and not worrying about the immediate gratification or pressure of ‘likes’ and number of views.

The discourse around the photobook is still evolving. We know that we’ve experienced some kind of a boom in the last decade; the pace of making and writing about the photobook has been tremendous. But we haven’t had time to process and assess what it all means. Nor have we really developed a critical approach to the form of the photobook. Having a shared language and taxonomy to describe and evaluate what we make is an essential part of the evolution of the field.