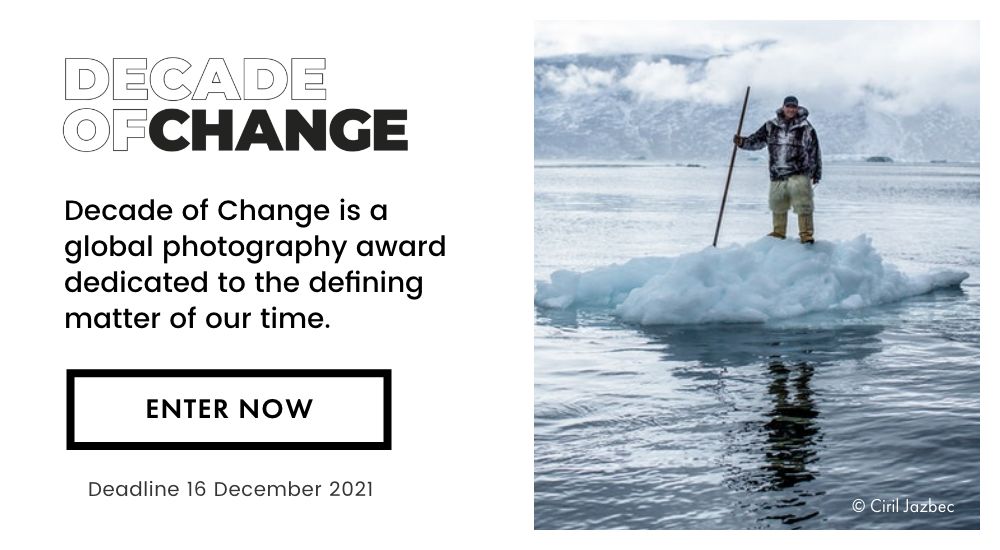

Climate change is eating away at the frozen Arctic Ocean, destroying what has historically been a protective barrier to Russia’s Far North. On assignment for The New York Times, Ducke travelled to one of the country’s new military outposts in the area, where he witnessed an awakening of activity.

For many countries around the world, climate change frequently targets precious sections of the environment in a cyclical fashion, with one devastating event opening the surrounding area up to others in the future. In Russia however, climate change is doing more than just leaving the country vulnerable to future environmental destruction – it is also leaving it vulnerable to invasion. Melting sea ice around its 24,000km-long border in the Arctic region is creating new entry points into the country, and with ongoing tensions between Russia and the United States, Ukraine, and many other nations, the Russian government has wasted no time in ordering the protection of this rapidly emerging frontier. It has begun deploying significant numbers of soldiers to the Far North, making it the first country to respond militarily to climate change’s growing impact on the Arctic.

Earlier this year, German documentary photographer Emile Ducke was invited by The New York Times to travel on assignment to Russia’s northernmost military outpost in the region. Based in Moscow and with significant interest in both Russian affairs and climate change, Ducke says he “jumped at the chance to see these huge changes first-hand and to capture them for a story”.

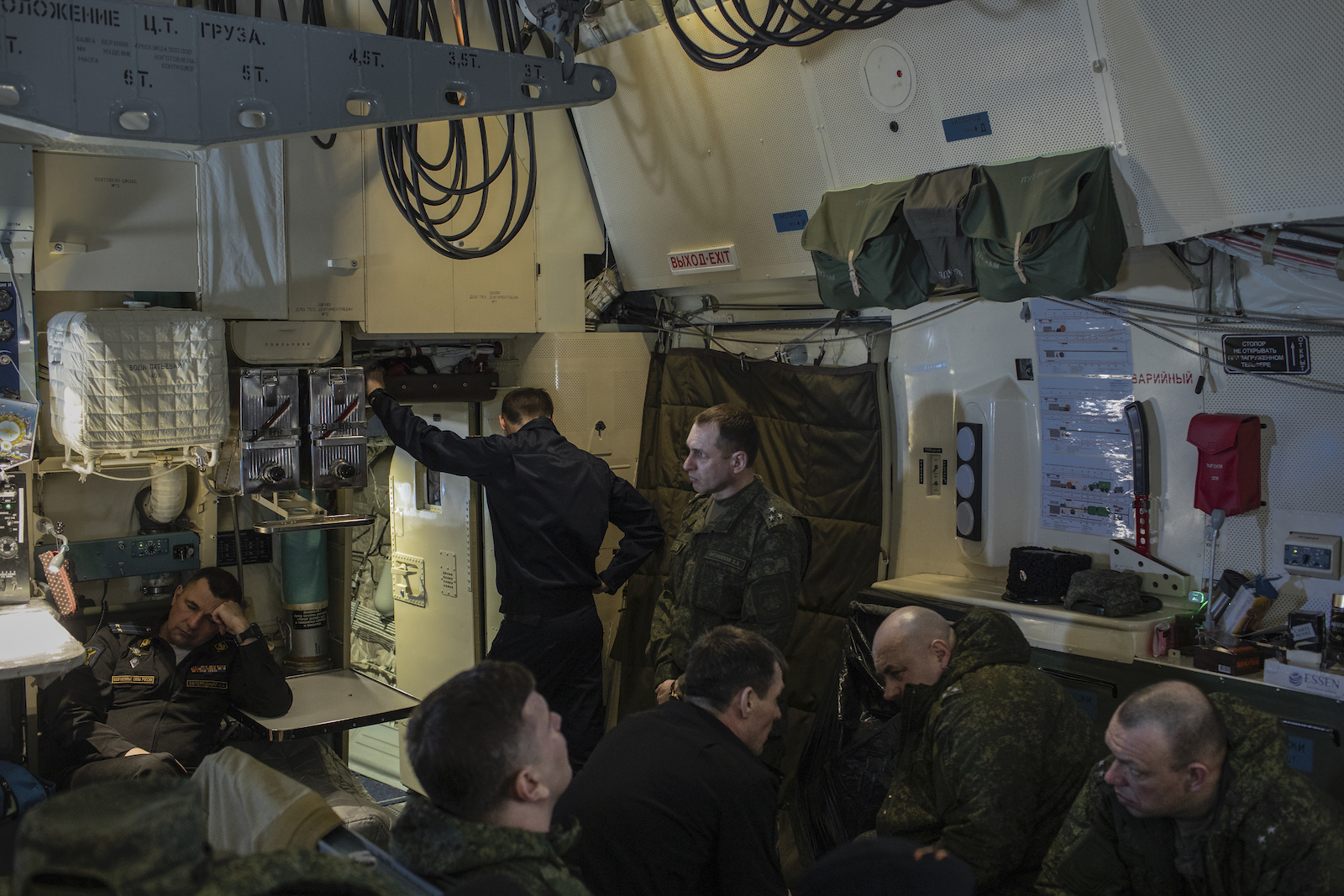

Alongside reporter Andrew Kramer, Ducke set off to document the Trefoil Base on Franz Josef Land, a glaciated archipelago in the Arctic Ocean, about 950km from the North Pole. “The trip was part of a tour organised for Russian and foreign journalists by the Russian defence ministry,” explains Ducke. “The ministry allowed journalists to visit some of Russia’s most remote and secretive military facilities in order to demonstrate its new capabilities in the region.”

“I was less interested in capturing these images than in looking for ways to tell the wider story of Russia’s Arctic deployment, and to offer a sense of the remoteness of the place. I was keen, too, to try and convey what daily life must be like for the soldiers posted to such a challenging corner of the Earth.”

After a period of adverse weather that left Ducke stranded in the nearby city of Murmansk for days on end, unable to leave the mainland, he eventually arrived at the Trefoil Base aboard a Ilyushin Il-76 military cargo plane. On arrival, he was immediately swept off on a tour of the facilities. The troops were busy making preparations for a launch of the Bastion anti-ship missile system and they were eager to demonstrate its power. As he explains, this “was a show of might” intended to awe friend and foe alike. But for Ducke, his focus lay elsewhere. “I was less interested in capturing these images than in looking for ways to tell the wider story of Russia’s Arctic deployment, and to offer a sense of the remoteness of the place,” he says. “I was keen, too, to try and convey what daily life must be like for the soldiers posted to such a challenging corner of the Earth.”

The sheer isolation of the military base is shown in Ducke’s photos of the various facilities, which are almost disappearing, “against a backdrop of such white emptiness that the horizon becomes difficult to discern”. In every image, this icy void envelops the few figures and buildings that make up the base. The only cultural sign on the frozen expanse is a tiny wooden church that stands in juxtaposition with the sterile metal structures nearby. Elsewhere, an icebreaker can be seen clearing a path for a cargo ship following closely behind. Ducke says he remembers the silence that surrounded him as he watched the ship slowly making its way through the ice. He remembers feeling “as if we were at the end of the world”.

The sluggish movement of solitary ships and the small, reclusive groups of soldiers may soon be a thing of the past, however. With the Arctic melting at an unprecedented rate, Russia’s Arctic border is rapidly becoming easier to navigate, raising questions about how this will affect activity in the region.

In the event of war, Russia’s formidable size may prove to be its greatest weakness – whereas the frozen Arctic Ocean once acted as a barrier to the land, it is now transforming into a large access point. Military outposts like the Trefoil Base have been set up as a deterrent to any countries that may be interested in the changes unfolding in the area. NATO, for instance, has already begun sailing convoys of ships into nearby waters, testing the Russian response to its presence.

But according to Ducke, an increase in military operations may not be the only result of the Arctic’s opening up. He believes that disappearing ice may also act as an invitation to the Russian people. Looking forward, he says “I am curious how the increased access to the Arctic and its resources will affect communities in Russia’s Far North. Many of the settlements on Russia’s Arctic borderline have faced a massive outflux of population since the collapse of the Soviet Union, but as it becomes more accessible this might change, possibly bringing new life to a remote and isolated region.”