We move into the adjacent workshop, which Simpson describes as “a place to bring things together”. The space is chaotically organised, centred around a large screen-printing press that doubles up as a desk, and is littered with newspaper clippings, magazines and old adverts. Simpson opens the door to a cast-iron wood burner – a feature he installed to counteract the stable’s lack of insulation – and fills it with a large log. A cloud of oak-tinged smoke fills our nostrils and the studio, with its ad hoc arrangement of scrap metal, paint-strewn furniture, tools and books.

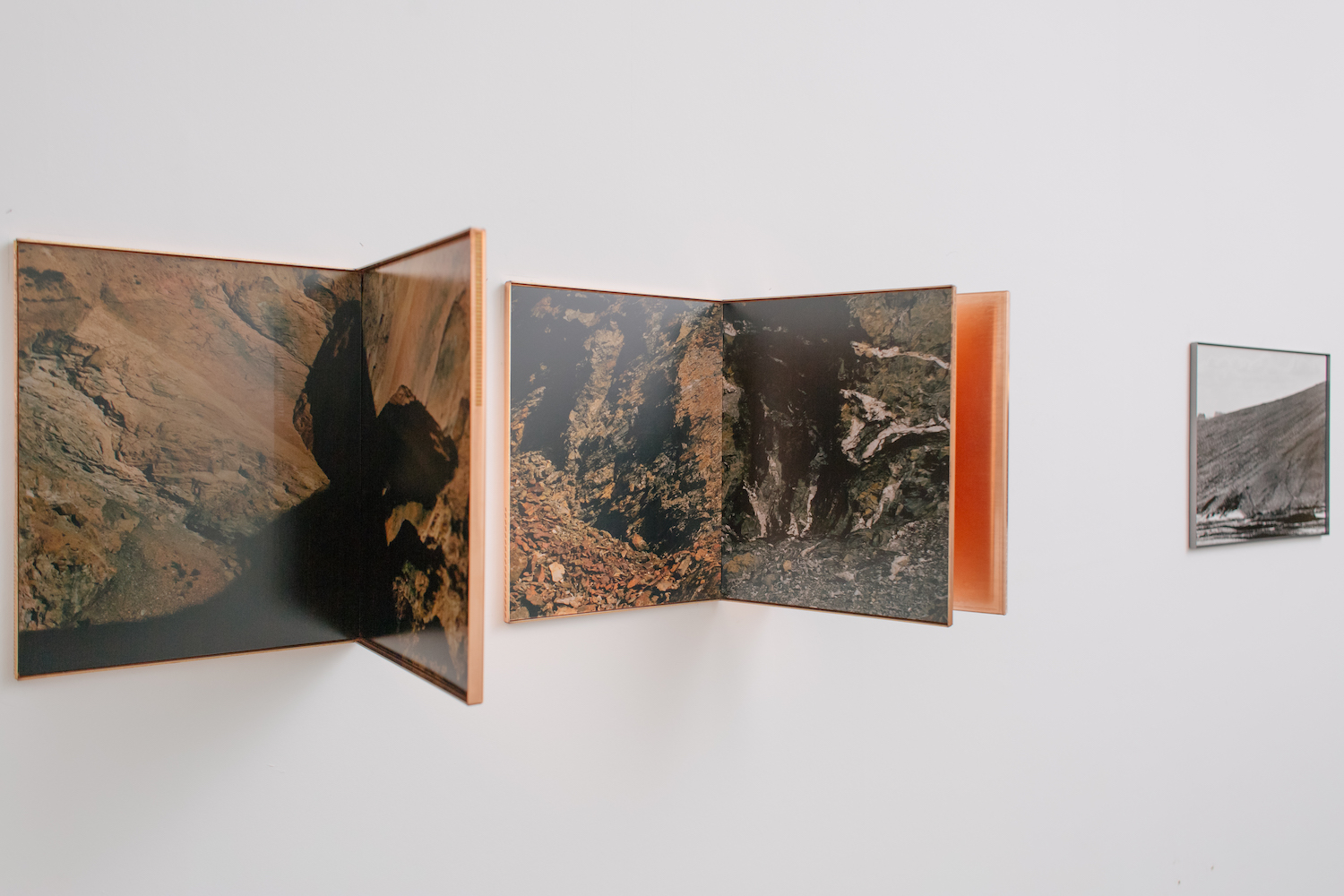

Simpson’s background is in landscape photography, he explains, but his current work pushes the boundaries of the medium. “I learned early on that it isn’t just photography that has language,” he says. “In fact, the photography on its own has very little because it lacks context. The things around a photograph give context and reveal something which the photograph can’t do on its own.” In recent years, his work has grown to incorporate metals, both for framing and for printing onto, and natural materials such as limestone and sediment. These elements have pushed his practice in the direction of sculpture, incorporating techniques such as laser-cutting, welding and fabrication. Where possible, Simpson performs these himself, but for larger works he outsources to local specialists. “It’s been a good way to connect with the people around me,” he says. He describes how, due to his stint in London, some of them jovially call him a “city slicker”.

Another core part of Simpson’s practice is appropriating archival imagery. Sometimes the new images have little resemblance to the original. For example, he might take a subtle sliver of colour from an old car advert, then enlarge it. These details often go unnoticed by viewers, who may not appreciate the history of the colour tones. “By introducing more elements, as well as expanding on the language of photographs, I’m introducing a wider field of discovery and scope of opportunity,” says Simpson, pausing to consider his words. “In a way, a lot of these nuances are for me.”