All images © Alice Zoo

Nearly a decade after winning BJP’s Breakthrough Single Image award, Adama Jalloh has become a trusted portrait photographer, shooting FKA Twigs, Little Simz and more. Based in London, the city where she grew up, she is now contemplating her next move

I first photographed Adama Jalloh almost 10 years ago. We met at the since-demolished Aylesbury Estate, south London, where Jalloh was working on early projects; she had recently won the BJP Breakthrough Single Image award with a photograph from her project You fit the description. The atmosphere that day was tentative, for both of us, two recent graduates in their early twenties, looking uncertainly towards a life behind the lens. Since then, Jalloh’s rise has been meteoric. She is a respected portraitist whose subjects have encompassed FKA Twigs and Little Simz, her clients including Alexander McQueen and British Vogue, and her visual language – high contrast, usually monochrome – always recognisable, whatever the assignment.

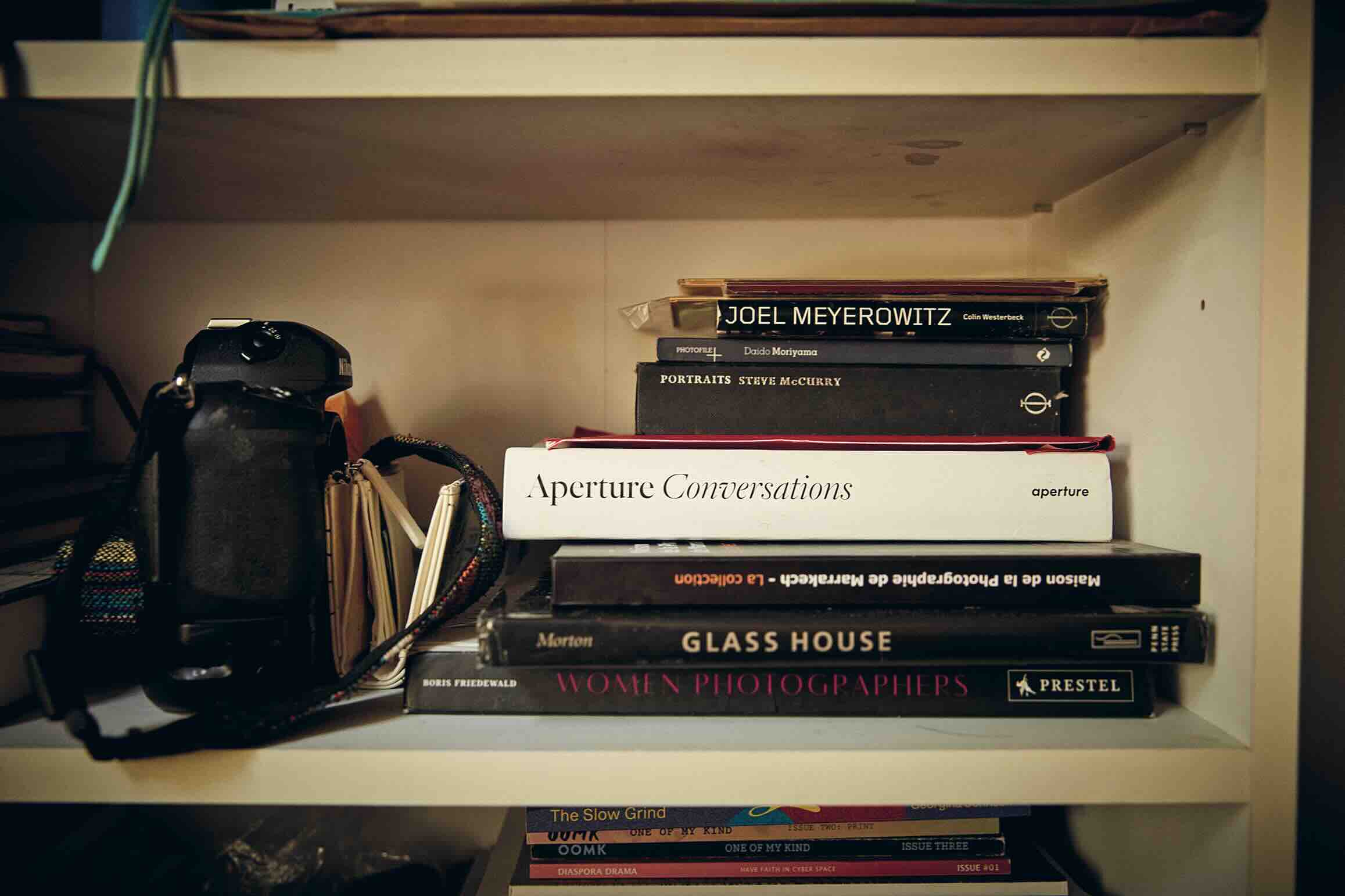

Jalloh’s early subjects were all family and friends. She recalls her initial shyness, and the way she began to “warm up” by photographing those close to her. As an undergraduate at Arts University Bournemouth, she was drawn to the work of the street photographers of 1960s New York City, looking closely at the black-and-white work of Mary Ellen Mark and Bruce Davidson; inspired by their urban observations, she began repeatedly returning to London, her hometown, to make projects. “That was the period when my eyes started to open to how much I appreciated London, because I was somewhere that I didn’t necessarily connect with,” she remembers. “The way I was seeing London around that time was like, ‘Oh! Everything feels very bright’.”

Increasingly, the city became central to her work and in her third year, she began explicitly to make projects “connected to the area that I lived in, or where I’m from heritage-wise” – Jalloh’s family background is Sierra Leonean – “leaning into that, and seeing where things would go”. This commitment to place, and intimate connection to her lived environment remained important after she graduated and began to make her first forays into assignment work, and has never ceased. “I always tried to make sure that the way I would approach my personal work would still be embedded in the commissioned work, if the capacity was available,” she says.

“I’m thinking more about my process – allowing myself to experiment, allowing myself to make mistakes, allowing myself to figure out what my flow is”

“That was such an interesting time, coming out of uni and already getting an idea of what it’s like to do commissioned work based on personal work,” she remembers of 2015, the year of our first encounter. The BJP Breakthrough Award exhibition had led to Jalloh’s first editorial commission after Emma Bowkett, director of photography at FT Weekend Magazine, saw her work and asked for a meeting. From there, Jalloh was soon shooting regularly for magazines such as Clash, until celebrity portraits and working on sets with several assistants became a matter of course.

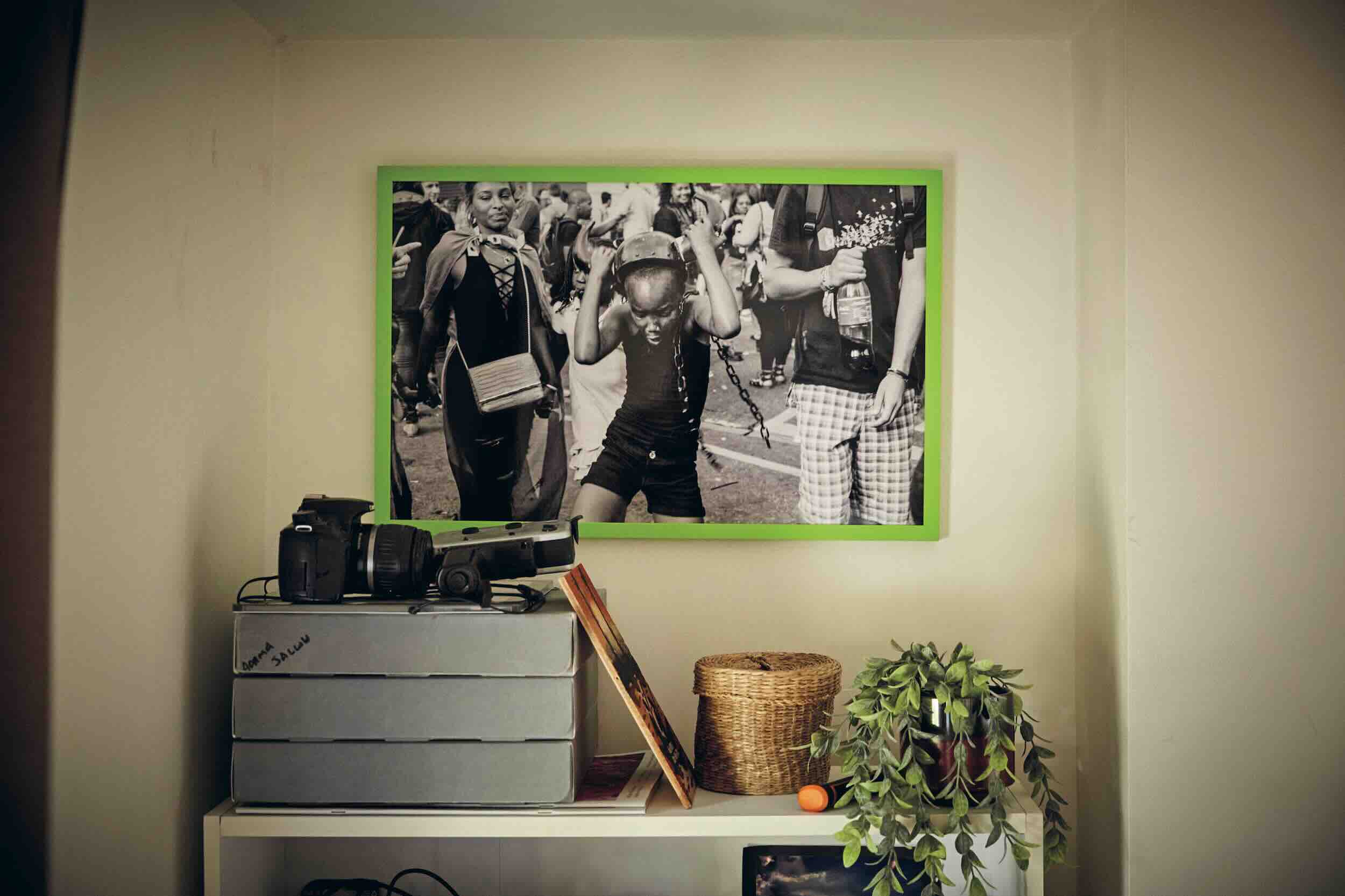

Accolades aside, the essence of Jalloh’s work remains rooted in the places she knows most intimately – the memories so much part of the fabric of her life that it took her a while to recognise them. “I always wanted to photograph the experiences I had when I was younger – the hall parties that I would go to, or always being with my cousins, or seeing kids playing in the park after school, being silly,” she says. “Growing up, I would look at those things and be so used to them that maybe I didn’t appreciate their beauty. When I really was getting into the flow of shooting every day, my perspective changed. It intensified my empathy.”

She has long described her work as a kind of visual diary, “embedded in how I was raised, what I was around, my own life experiences”. This diary, while recorded in photographs, is something that Jalloh experiences as three-dimensional and multi-sensory. “When I look back on my images, I can really hear them,” she says. “And even though a lot of them are in black-and-white, there’s this vibrancy that I can feel.” There is a palpable sense of her desire to communicate this fullness of experience; for the viewer to feel it too.

Until last year, Jalloh worked in a studio space that she took up during lockdown. “When I initially moved in, it was so quiet,” she recalls. “It was just me. It was the perfect time to step into that world, separating my work from where I lived, having the room to think somewhere else.” She made portraits and commissions there and began to paint, and, when the Covid rules were relaxed enough, invited people for meetings and studio visits. “It was a good time to be able to explore my thoughts and feelings, and to really see my work in a physical way, in a physical space,” she says. “I was actively going out of my way to see how my images make stories. It was a good way to see how else I could think about approaching my work moving forward.”

The decision to part ways with the space last year was bittersweet. “The rent was too high, it just didn’t make sense,” she explains. “It almost felt like I’d be paying house rent money. It was a shame, but then again I was at this place where I was actually OK with letting it go.”

At home in Bermondsey, where her life and practice are once again intermingled, her prints are on the wall again; the house is full of her work, framed beautifully and hung throughout her living space. The shift away from the studio and back towards home has occasioned a moment of deep reflection for Jalloh who, a year before moving out, had already begun the lengthy process of archiving a decade’s work. In doing so, she had cause to look closely at her beginnings, for the first time in years, the ways she moved as a photographer, the things she saw, what she prioritised.

“I was very much in a different place in my life,” she recalls. “I was thinking about how I would use my body when I was outside, for example – like the way I would approach street photography. I was chasing the light all the time, and using my eyes, my ears, and other senses to be able to capture things. If I’m hearing kids running from the side of the road, I’m already prepping my camera. If I’m hearing aunties having conversations I’m already chasing light – because I can see the light is going to hit them in a certain way, so I’m running to the other side of the street.

“I definitely used to carry my camera around with me everywhere,” she continues. “I went through a period of shooting every day. I think it was a good practice of allowing myself to just shoot, rather than overthinking the process.” Her years photographing on the street eventually cohered to form a discrete body of work, Love Story, an archive of a particular place, at a particular time; the Black communities of south London, at play and at rest in the light of summer.

One of the biggest changes she has observed in this moment of archiving and reflection is a difference in speed. “I’m a lot slower, which isn’t a bad thing,” she reflects. Working in the studio, where light can be meticulously controlled, required a different muscle to the dynamic nature of the street in British weather, and as a result Jalloh grew accustomed to a more measured pace. “Maybe it’s also an age thing,” she adds. “I’m wanting to take my time. I’m ready to move quite slowly, and really take the time to see where this new way of working might manifest.” She is more seasoned now, a decade’s experience under her belt. “It’s interesting, coming to that conclusion and being OK with that.

“There’s so much to absorb when you’re outside, and there’s so much to play with,” she says of her fleet-footed approach to her early work. In the studio, with an adjusted pace, the rhythm was more subtle, allowing for more patience. This shift led to a deepening of her approach to portraiture, informing the contemplative character for which her work is celebrated. “I feel that now I’m drawn not only to capture a person in their essence, but also to hear what they’re about. There’s a lot more bonding,” she says. The sensitivity she cultivated to light and movement in the street was tuned instead to shifts in mood and narrative in her relationship to her sitters.

“I’m taking the time with where they’re at,” she says of her process today. “I like hearing other people’s stories; I like being able to know how they’re doing, see how they’re feeling in that moment. When I ask, ‘How are you feeling?’, you can tell at a certain point after having the conversation they’re…” she pauses, searching for the right word. “Lighter.”

I observe how closely her commissions have seemed to align with her personal work, that her commissioned portraits seem to live in the same world as those of her projects. “It’s great to have that, where it feels like things can merge together,” she agrees, “but I do also feel like I’m wanting to track back a little, to how I was approaching things when I initially started shooting – when it really felt like I had the time, and there was a bit more purpose around what I approach and why.” As with many working photographers, there is the ongoing question of how to balance these two commitments – the imperative to make a living, and the necessity of creative experimentation and play. “I think I’ll probably always end up bouncing between the two,” she admits.

For now, her focus is turning back towards personal projects. “I’m hungry to start making work again, and figuring out what I want to do, how I want to do it, where I want to go,” she says. This moment of reflection, of taking stock, is part of that. “I’m thinking more about my process – allowing myself to experiment, allowing myself to make mistakes, allowing myself to figure out what my flow is. Allowing myself to have fun with it.”

Jalloh is slowly imagining what this new work might look like, what shape it may eventually take. She is photographing, painting, watching films, making pottery; she is going to the Stuart Hall Library in Pimlico, pulling out references and studying. She is drawn to the idea of photographing somewhere different, perhaps abroad. “I want to see how things go when I’m in a different place, what my photographic language looks like,” she says. “What are the similarities and differences? What are the new things I pick up along the way that I choose to bring with me when I’m photographing things at home?”

But wherever she lands, her values will remain, and will remain central. “I want it to feel timeless, and I want it to feel hopeful, and I want it to feel intimate,” she says. “And also, when you’re looking at it, you can hear it.”