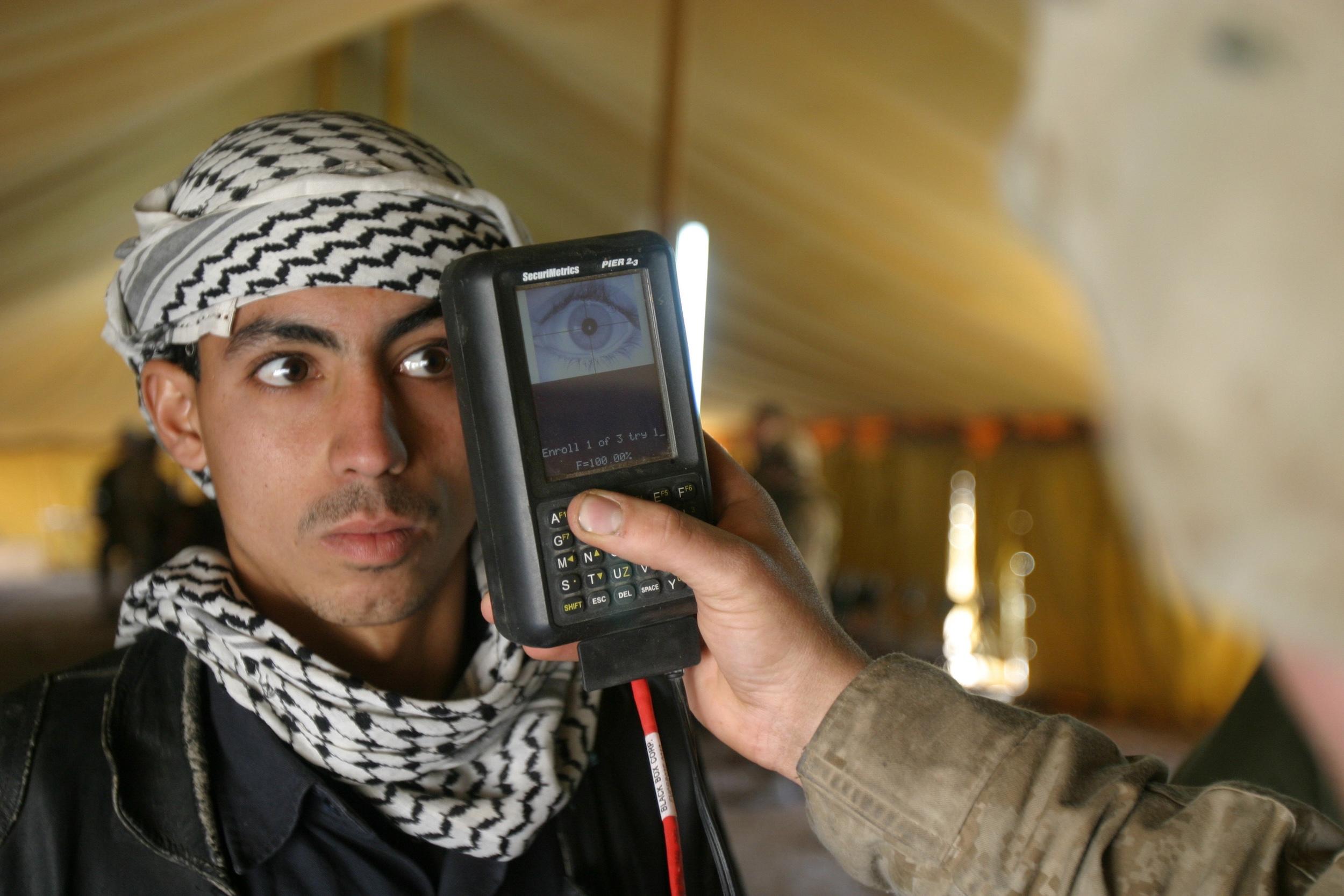

Marine Lance Cpl. Luis Molina scans an Iraqi citizen’s retina at Brahma Park in Fallujah, Iraq, on Jan 25, 2005. U.S. Marines are utilizing a Biometric Analysis Tracking System to record and identify Iraqi civilians entering the battle torn city of Fallujah in an attempt to find and identify insurgent forces. The tracking system uses thumbprints, a photograph of the face, and a retinal scan to establish positive identity. Molina is deployed with Marine Wing Support Squadron 373 in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. DoD photo by Staff Sgt. Jonathan C. Knauth, U.S. Marine Corps. (Released)

Delving into the jaw-dropping global spend of the US Department of Defense, Edmund Clark and Crofton Black have delivered a portrait of a country that also speaks about everywhere else

Edmund Clark and Crofton Black’s new book is titled Cosmopolemos, a word they have coined to describe “The ordered universe of war”, combining ‘kosmos’ (or ‘order’) with ‘polemos’ (or ‘war’). The book’s subtitle is An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of The United States of America Department of Defense Contract Spending 2001/09/11 – 2021/08/30, and as this suggests, it is at its simplest a breakdown of American defence spending over a 20-year period. More elusive is what it suggests about a universe of war, and the way we can interrogate and understand it. Cosmopolemos is an oblique portrait of the US, but it also speaks about a world order, as well as about order itself.

Clark is a photographer, known for his work on the military-industrial complex and how we might – or might not – be able to represent it. His 2010 publication Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out shows eerie empty scenes at the infamous US base in Cuba, while Control Order House, first published in 2013, depicts an apparently ordinary suburban home in which an individual suspected of terrorism was indefinitely detained by the British government. Black is an investigator and writer who often works with open-source intelligence, collating and interrogating publicly available information to give insights into otherwise opaque systems. His work on secret CIA prisons in Eastern Europe led to landmark litigation at the European Court of Human Rights, while his investigations into telecom surveillance have been supported by Lighthouse Reports and the Bureau of Investigative Journalism.

The pair have worked together since 2011, when their paths crossed at UK human rights NGO Reprieve; in 2016 they published Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition, which uses documents and photographs – sometimes redacted, and sometimes pixelated – to indicate CIA ‘black sites’, and problems of representing them. Negative Publicity tapped a weak spot in the Central Intelligence Agency – its fiscal accountability, which leaves a trail of invoices, reconciliations and contracts with companies with which it does business. Cosmopolemos does something similar, delving into records of US Defense contract spending, which uses public money and therefore all has to be publicly declared (unlike the CIA). Specifically it is available via usaspending.gov, a mirror of the Federal Procurement Data System. “The whole of federal government spending is available if you want it,” explains Black. “But due to processing time and disc space we only ever downloaded the DoD. You can download it year-by-year, so we made 20 downloads then combined them into one data set.”

“On the one hand, the representation of the awesome and the enormous, the numbers too big to comprehend. But then also the incredibly small, the numbers we can identify with. Does that present a way of measuring oneself against this thing too big to comprehend?”

The 20-year timeframe was not accidental, and is bracketed by very specific dates – the 9/11 attacks on America in 2001, and the US withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021. In between lies the so-called ‘Global War on Terror’, and conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria. Clark and Black do not tally a final figure but they break down totals country by country, and in this period spending in the US alone totalled $5,874,988,003,583.80. Spending in Afghanistan totalled $108,283,549,712.16; though the largest share went to Fluor Intercontinental Incorporated, a subsidiary of the Fluor Corporation headquartered in Texas; $103,997,650,656.90 was spent in Iraq, but the largest share went to Kellogg Brown & Root Services Incorporated, HQ in Houston, Texas; $21,249,885,995.15 went to the UK, BP Oil International Ltd alone taking $2,315,864,044.77. The spend is enormous, so large it is beyond comprehension; Clark found himself rendering the totals as words, in order to better understand (described this way, the US Defense spending in America was nearly $6trillion).

But the figures are also weirdly specific. Costs are recorded to the individual cent, and the data broken down into granular detail, categorising each payment into individual products or services according to 285 alphanumerical codes. The overall data set Clark and Black downloaded contained 43 million records, from which they extracted some 60,000; they then selected some 20,000 for the book, focusing on the mind-blowingly large and the sometimes mundanely small. They included transactions ranging from multi-million-dollar weapon deals to $0.02 for a zipper (two inches long). “We were interested in analysis of scale,” Clark explains. “On the one hand, the representation of the awesome and the enormous, the numbers too big to comprehend. But then also the incredibly small, the numbers we can identify with. Does that present a way of measuring oneself against this thing too big to comprehend? Is it a way for people to see the connection between themselves and that which might seem more detached, exotic, or distant, which they have experienced on their screens?”

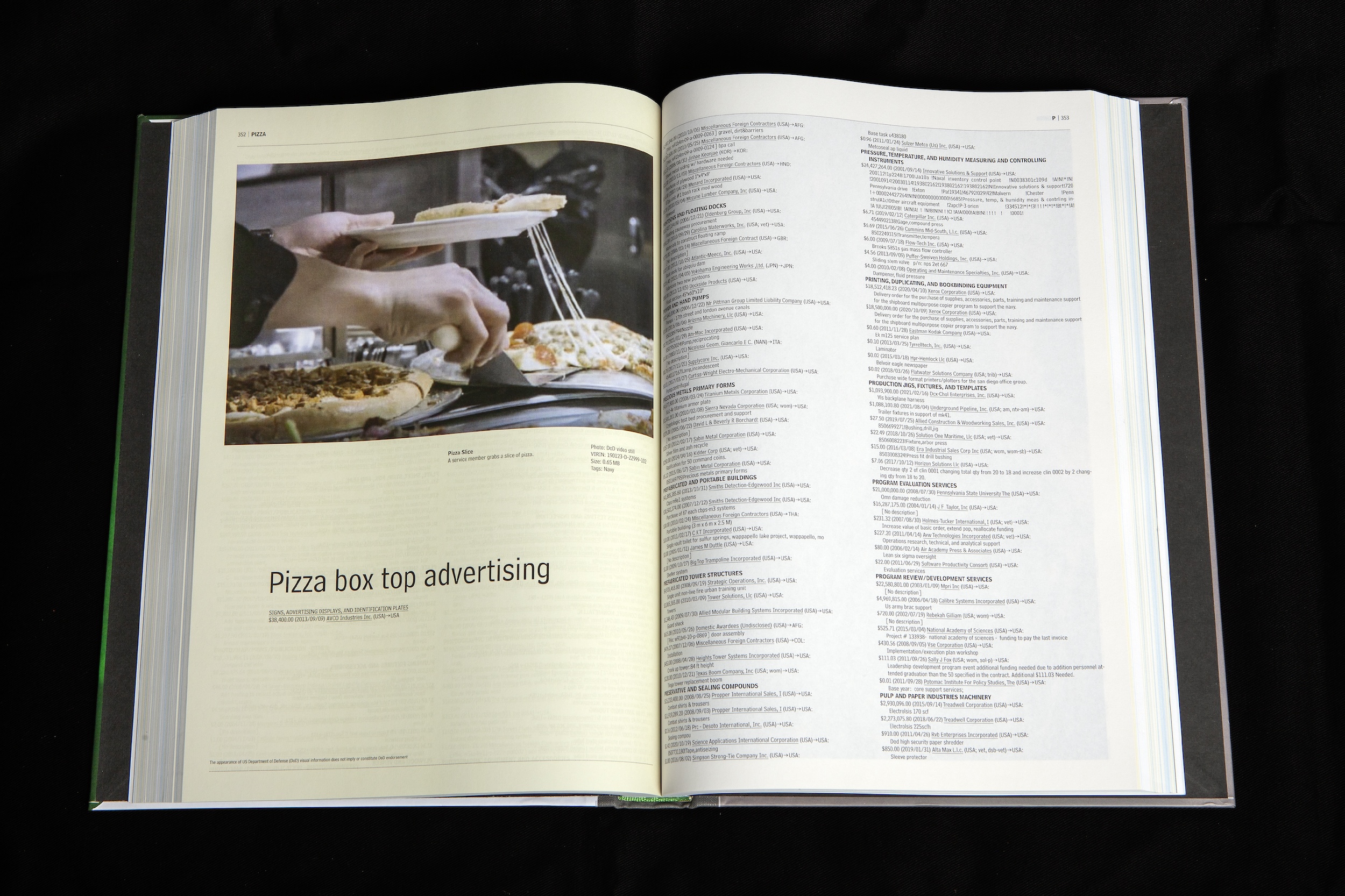

Cosmopolemos reproduces page after page of records and, as Clark’s comment suggests, the sheer bureaucracy is part of the point. Unlike spectacular events such as the 9/11 attacks, seen by most via striking press images, the lists of transactions are mostly dull. Dry records, including often-impenetrable codes and acronyms, they render even the extraordinary everyday. In 2009 $1million spent in Iraq becomes a “commercial contract award”, seemingly innocuous and, buried among items, barely eye-catching. Then there is the bizarrely relatable level, such as an ice-cream maker bought in 2020. “There’s apocalyptic stuff, then there’s the incredibly mundane, and then there’s the absurd,” says Clark.

“Chief Whipple wanted his name sewn onto his jacket, there is a pair of boots for one person, then pages about full spectrum dominance. We’re working with all three, but also absurd is the way we try to make sense of these things. We can’t.” Negative Publicity was about secrecy, but this is about something else; the impossibility of digesting these figures, or of ordering the world in this way. The data is quite literally flawed, partly due to the human element. Transactions are categorised according to dropdown lists, and sometimes the wrong category is applied, ‘Israel’ and ‘Iran’ mixed up in one instance, as they are next to each other in alphabetical order. In other cases multimillion dollar figures are declared, then almost immediately cancelled; someone has put a decimal point in the wrong place or added erroneous digits in error, small typos that are potentially hugely misleading.

But these errors suggest deeper epistemological problems too, with how one might categorise absolutely everything, and fit it in a pre-formatted list. Black holds a PhD in Renaissance theories of cognition, in older forms of knowledge and representation, and says applying these ideas to a 21st century example was fascinating. He adds that, fundamentally, the questions remain the same. “It’s just another expression of the hermeneutic circle – how do you know the parts if you can’t know the whole, and how can you know the whole if you can’t see the parts?” he explains. “That applies to maps, it applies to large bodies of text, it applies to databases, it applies to any collection of signs really.”

Clark and Black considered how to convey the data they had amassed, Black adamant it could not look like an NGO report, that there would be “no data visualisations, no pie charts”. They spent time at the British Library researching information and how it is presented, and eventually decided on an encyclopaedia, arranged in alphabetical order. Alphabetised encyclopaedias became popular during the Scientific Revolution, in the second half of the Renaissance, Black says, when they represented a radically new approach. Rather than the cosmology of Medieval Europe, in which items of knowledge existed in relationship with each other and a wider structure, alphabetical encyclopaedias simply ordered in lists. And they could also reel off into infinity. “The alphabet is the most convenient way to list an ever-expanding number of entities, without having to posit some kind of relationship between them,” says Black. “Encyclopedias essentially stopped forcing themselves to engage with wider frameworks as a matter of form, and instead just engaged with ‘Here is a big list of things’.”

There is a relationship between this approach to knowledge and a certain approach to society, with the new alphabetised encyclopaedias appearing just as the French and American revolutions got underway. “I don’t imagine we have got to the bottom of it [the connection],” Black chuckles, but he adds that such encyclopaedias have now been superseded. These days we rely more on search terms and hyperlinks, which abandon even an alphabetical structure for data. “Cosmopolemos is very much about representation and about how data is interpreted,” he adds. “How knowledge is interpreted, how knowledge is constructed, the kind of contingent nature of knowledge… How do we derive useful information from these millions and millions and millions of lines of stuff? What is our relationship with this information, and what does it mean to make it useful?”

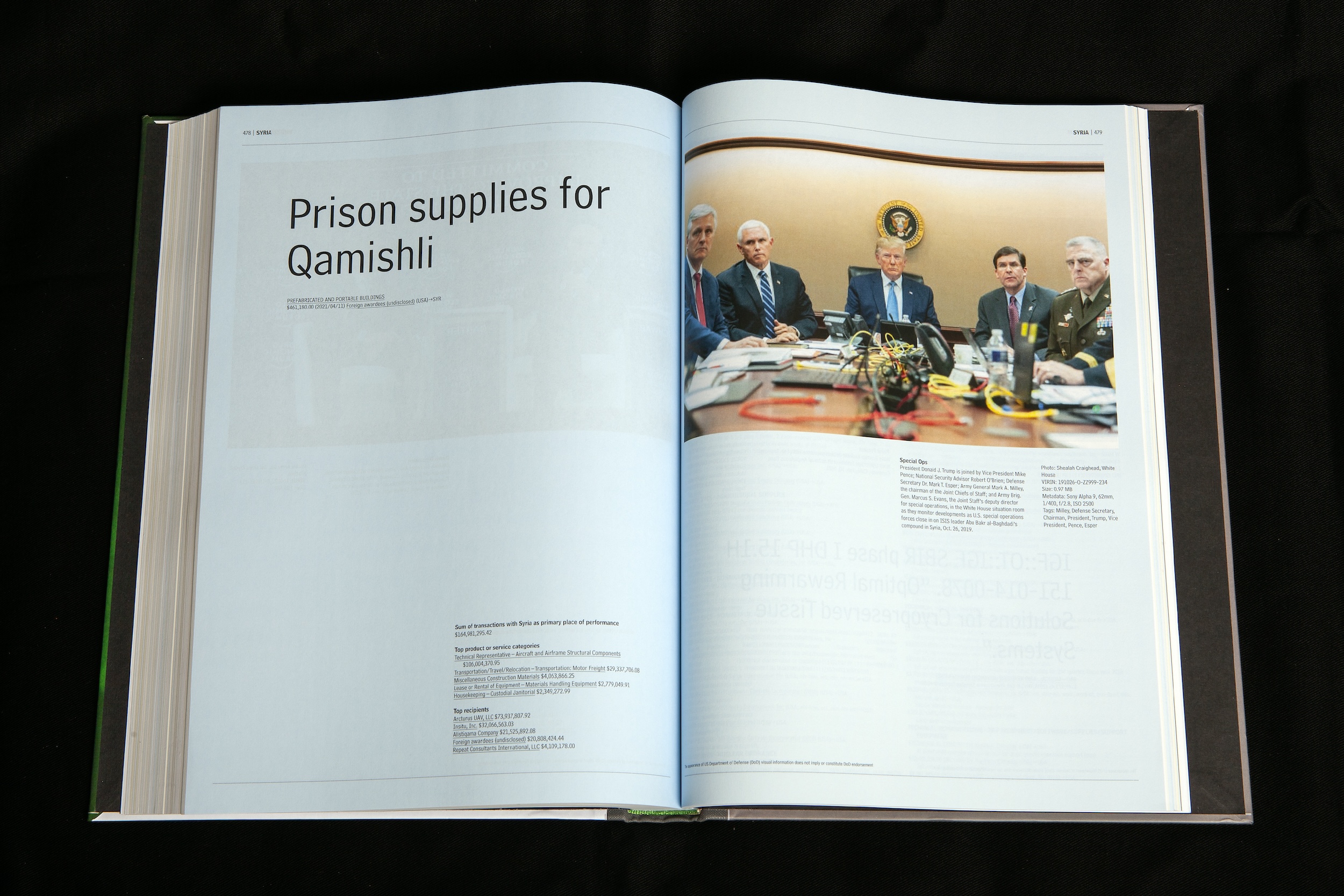

The data entries are also not the only elements at play. Interspersed among the transactions, Cosmopolemos includes pages which highlight particular details, on spreads coloured pale blue or yellow. Blue signifies a ‘gazetteer’ and organises information by country – like a geographical dictionary – another form popular in the past. Yellow pages signify a glossary, highlighting particular words found in various transactions and image captions, and are more like searching by term. These searches throw up some curious fellow-travellers. An entry for a “one-night stay in a two-bed room” sits beside an image of a detention unit in Guantanamo, for example; a small charge for “wasp destruction” abuts an image of Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld at a press conference, during “the multinational coalition effort to liberate the Iraqi people, eliminate Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction and end the regime of Saddam Hussein”.

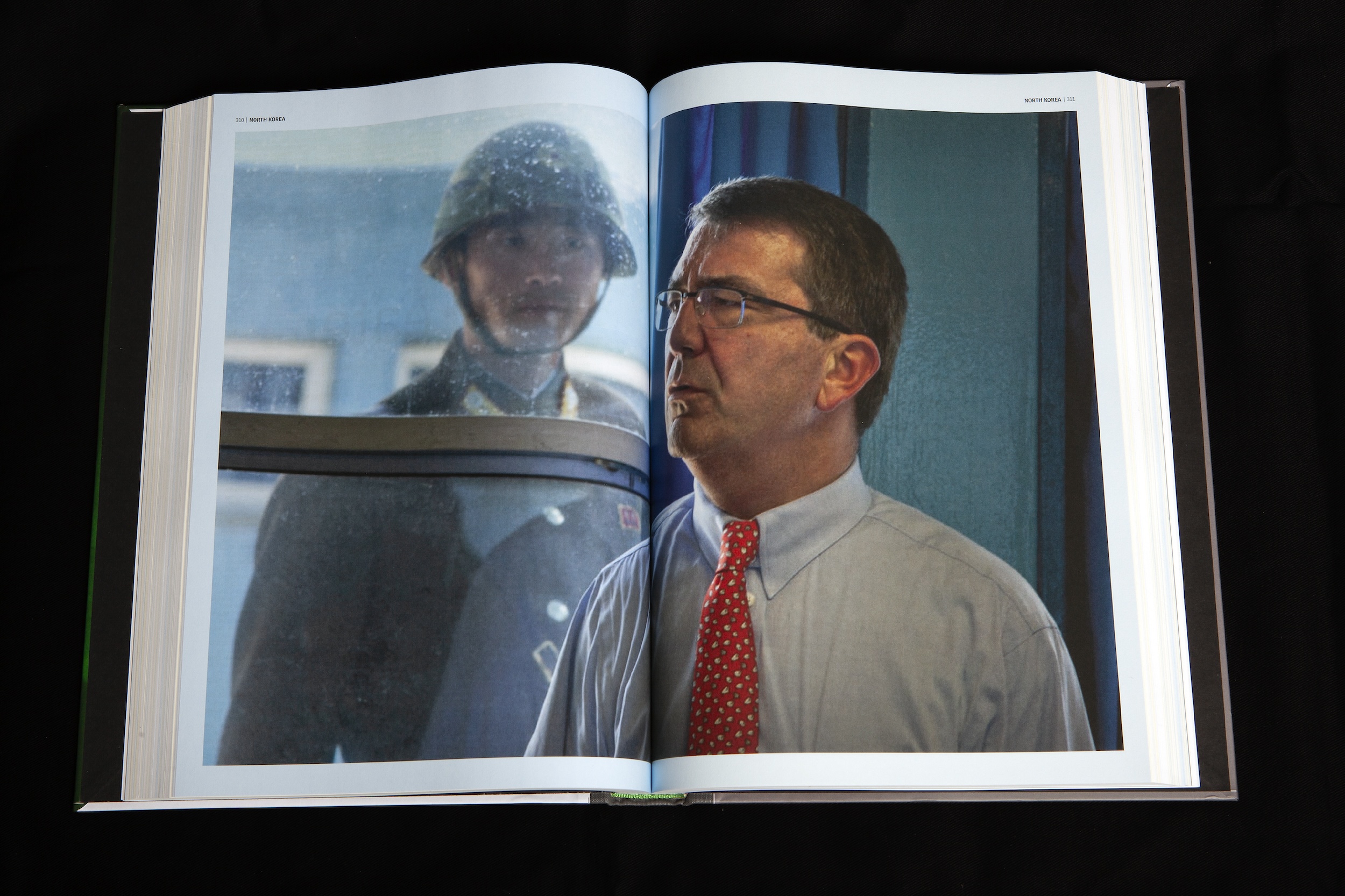

The images and captions are sourced via the DoD gallery, which contains about 2000 uploaded single images at any one time; there are also larger databases of photographs, which sit behind this public front end. The images, plus captions, can be freely downloaded and used, provided they are run to include a disclaimer: “The appearance of US Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement”. Disclaimer or not, the images plus captions are an expression of DoD soft power, and present its work in a positive light. There is a shot of a sergeant carrying a dog over a rubbish dump in Iraq, and another of four forces wives at a cookie drive. There is an official portrait of Lisa Hershman, chief financial officer of the DoD, and images of numerous meet-and-greets, including a conference featuring Prince William and his wife Catherine.

There are images including guns and planes but Clark mostly avoided what he describes as “the technological sublime”. Clark was not given a clear explanation of why these photographs are made available, or who uses them. But they are clearly PR for the DoD, “generated to represent what the Department of Defense wants to be seen of its activities”, as he puts it. Some have been uploaded by individuals described as ‘mass communication specialists’, whose job is to make images for wide dissemination; Cosmopolemos includes

the ‘Situation Room’ shot by Pete Souza, then-chief official White House photographer, showing Barack Obama and his national security team watching on-screen as Osama bin Laden was assassinated in Pakistan. These images can and do run in the media, and images on the DoD website are often also made available elsewhere, sometimes at higher resolution. Where possible, Clark has downloaded the better-quality versions, and always included the captions and credits. “The captions are really important for the images,” he observes. “They are another representation of how DoD power is made, or made manifest.”

Like the financial records, the images give the appearance of transparency, of an apparent willingness to be open with the American public (and beyond). But the views on display are partial. Some of the transaction records include only vague details, skating over what has been bought and why; none of the itemised costs speak of their impact on people’s lives or bodies or minds. Similarly the images do not show the dead or wounded, or landscapes devastated by war. They are often weirdly anonymous, depicting Marines playing basketball in Iraq, or Afghanistan, or Germany, or somewhere out at sea, on courts which could be literally anywhere; other photographs show meeting rooms whose locations are equally inscrutable, beyond the captions. Individuals are often anonymous too, with one image of “Marine Lance Cpl Louis Molina scanning an Iraqi citizen’s retina” giving more information about the photographer and camera than the individual who takes up most of the frame.

This apparent anonymity is not neutral; what is on show is American power, imposed all over the world. And the transaction records suggest something similar. Reducing everything to a figure, they entangle seemingly everywhere in a financial web, payments and micropayments amassing into a single rule united by cash. Clark and Black’s book is subtitled ‘the ordered universe of war’ but if it is a ‘universe’, it is one constructed and governed by the USA. How this will pan out in future is moot. As Clark points out, the 20-year period under consideration may signal a high-water mark, the greatest spend the USA has ever made or will ever make though, writing as the US bombs Iran while Trump talks of regime change, it is clear American nation-building is not over. But with billion-dollar sums going to BP, and primary school pupils in Bury St Edmunds “given the chance to interact with American service members”, what is perhaps more surprising is how far we are all embroiled.

Cosmopolemos: An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of The United States of America Department of Defense Contract Spending 2001/09/11 – 2021/08/30 by Edmund Clark and Crofton Black is published by Steidl. It is on show at Photo Oxford from 25 October to 16 November 2025