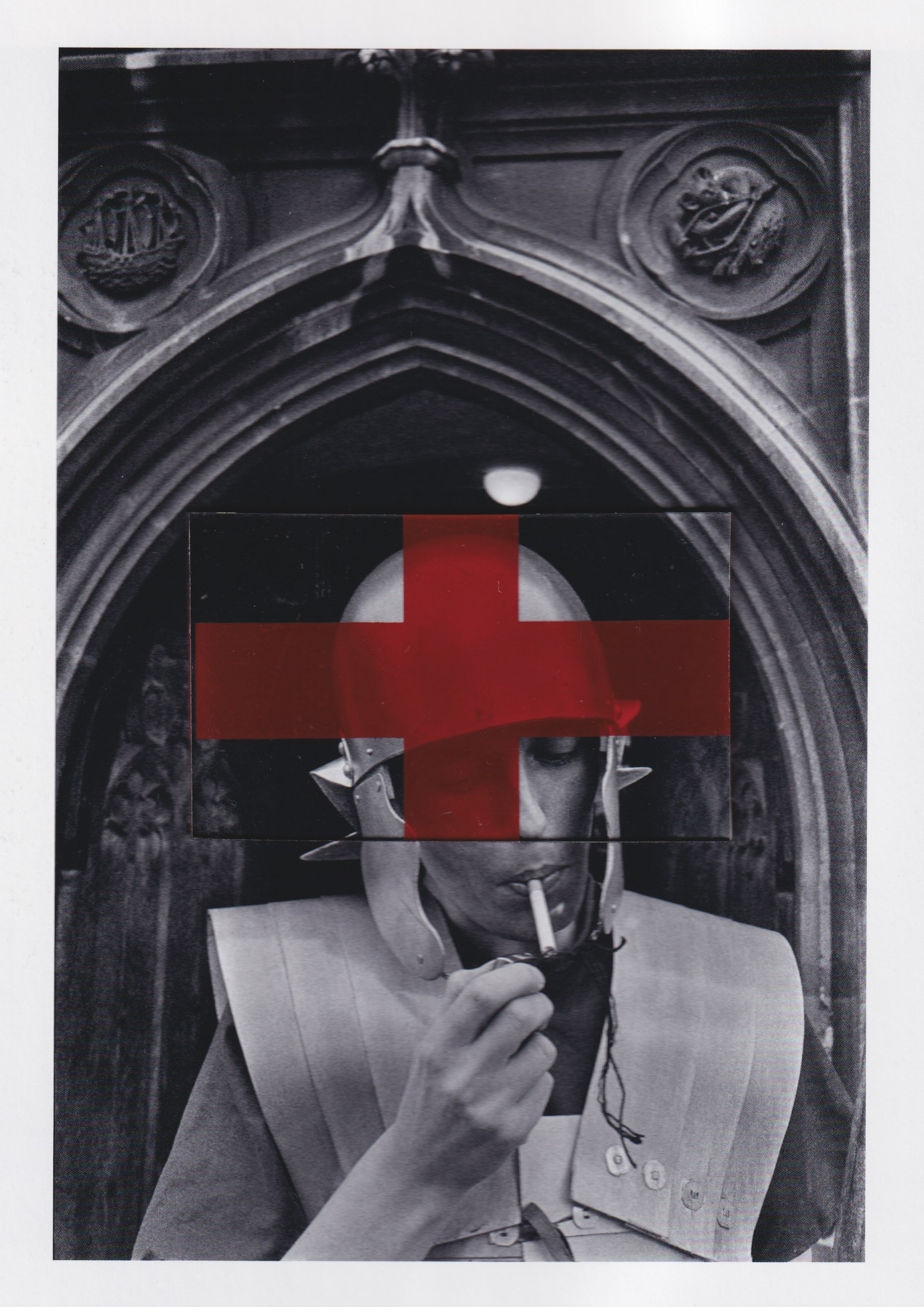

Zineke Diikstra, The Nugent R. C. High School, November 1994. All images from 100 Glass Crussiforms © Mohammad Tariq.

With a simple glass device, the London-based Pakistani-Bengali artist turns archival photo books into sinister revelations on British colonial histories

Though Mohammad Tariq has long been experimenting with materials and creating multimedia pieces – inspired by his family’s textile background – his formal training lies in the world of law. It was this interest that led him to creating 100 Glass Cruciforms, a body of work which intervenes in found imagery from across the globe, mostly within photojournalism but also popular media, to excavate and uncover an imperialist world view and the intersection of gender, white supremacy and geopolitical conflict.

Tariq, a Pakistani-Bengali artist, Social Media Editor of video platform Nowness and Contributing Editor of South Asia Archive, lived between East London – where he is currently based – and Jeddah, Saudi Arabia until the age of 13. His grandparents had settled in London in 1963. Tariq’s grandparents, like many South Asian diaspora in Britain, worked in the textile industry: his grandmother owns the store Alina Fabrics. So, he tells me, he’s “always been very tactile. My grandma’s shop is where my tactility and visual language are rooted. That tactility began at the foot of my grandmother’s and mother’s sewing machines, and sleeping between fabric rolls.”

His previous bodies of work include a series of what Tariq describes as “material reactions” which use jewellery and sculpture to critique identity and class politics in Britain from a diasporic perspective. Using jewellery, he would play with symbols of power using, for example, the second-class stamp which signified the ‘second-class citizen’ in his work.

“When I started studying law, the legal practice and the artistic practice began to converge because I was researching colonial history. As I went deeper into my legal research,” Tariq tells me, “that’s when it started to get a lot more conceptual and I started maturing a little bit more as an artist. I wanted to pursue human rights law but I also wanted to converge that with my visual practice to communicate the research that I was, and still am, doing.”

When Tariq came across slides of negatives of an Essex family from the 1960s in a charity shop in Cambridge a year ago, he began manipulating the images, effacing them in different ways. The images depicted “their general life, a quintessential English family holiday in Mallorca; it’s all there.” He started to take the slides apart, “and I feel a bit bad, but I scanned the images before, then I started disrupting the images.” For Tariq, there was a sense of complicity within the images: “I think seeing a quintessential English family for me during the 60s, when I have images of my grandparents at the time engaged in hard labour, working factories and understanding the context of what they were going through while this family in England were by the sea… it made me uneasy.”

Onto one of the images, he scratched a St. George’s flag with a pin; “I don’t know who this family is,” he says, almost sheepishly. “So I do apologise to whoever they are! I’m sorry your images ended up in a charity shop and they found their way to me,” he laughs warmly. Though the act of disruption is simple here, Tariq attempts to point to something more complex, to the idea of complicity with a “colonial decadence, that the context of [the family’s] lives was built by years and years of subjugation of racialised bodies around the world.”

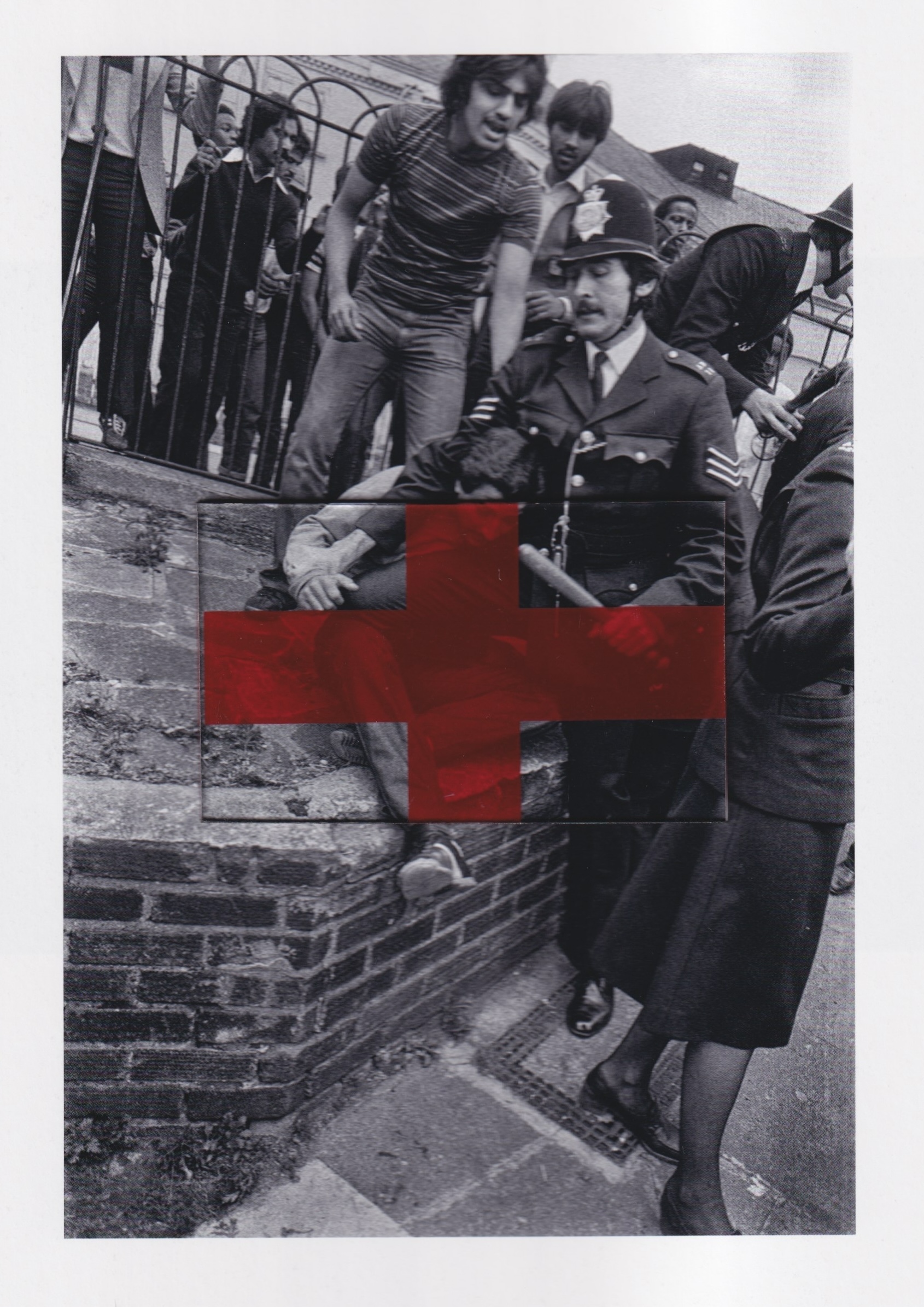

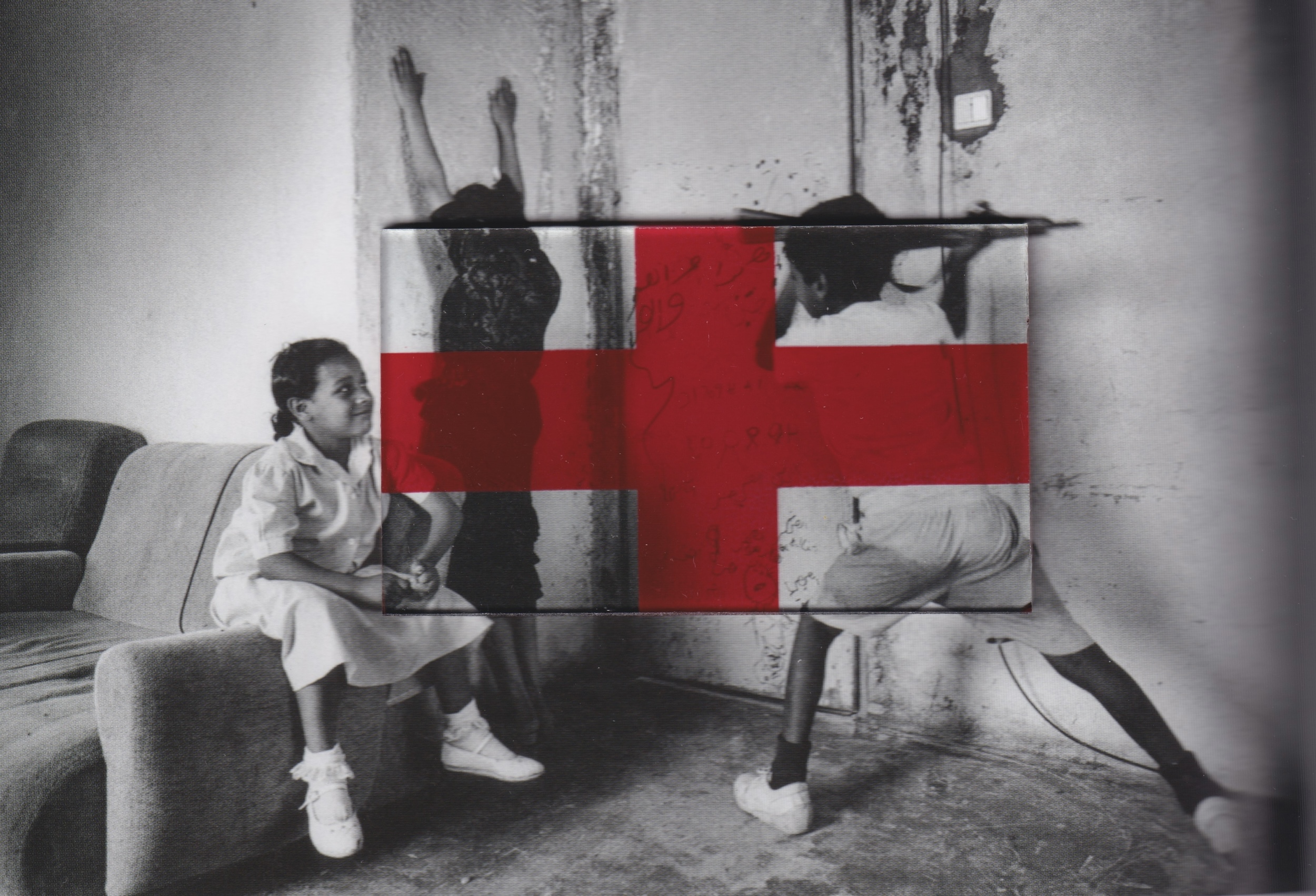

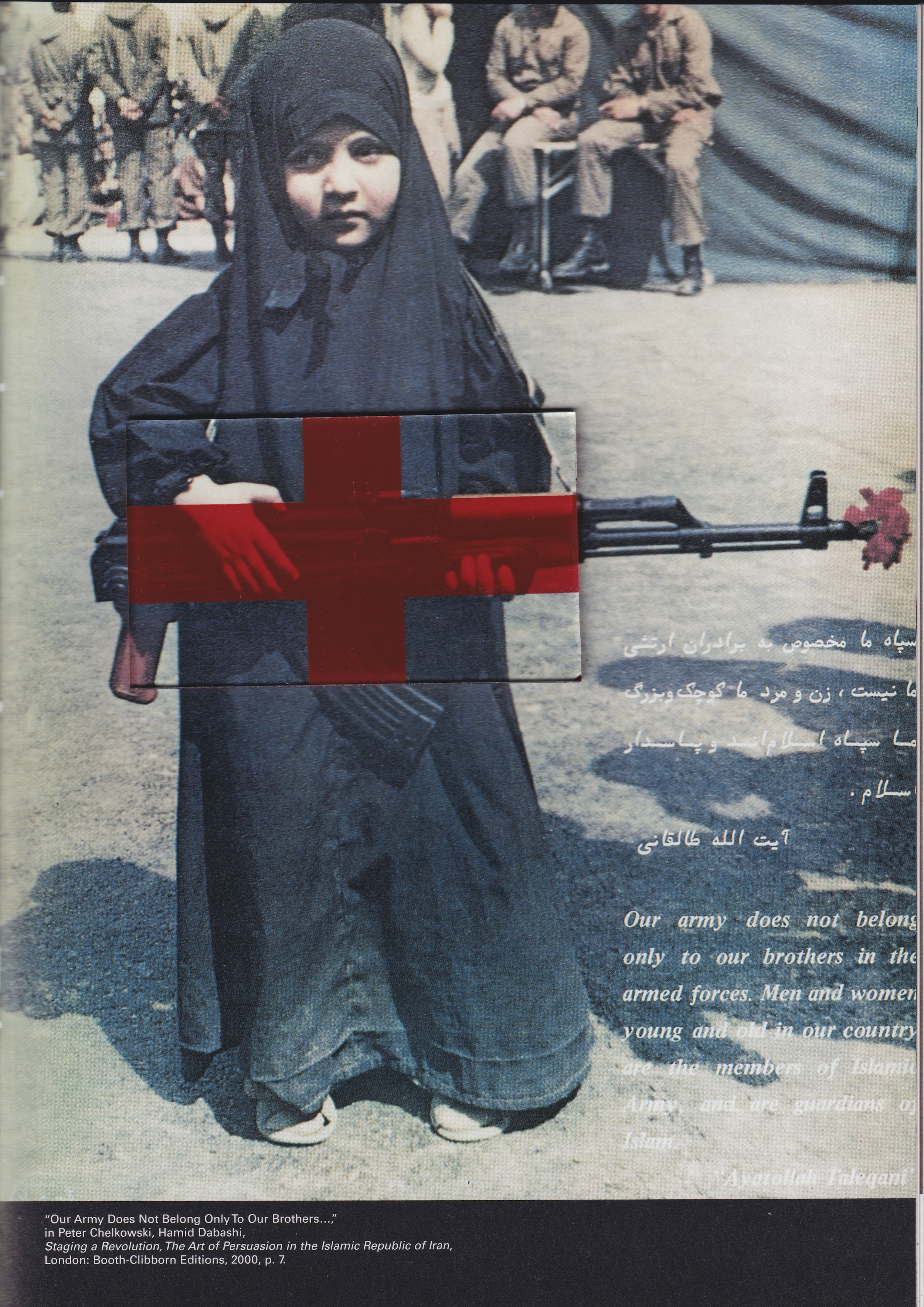

From there, the artist developed a glass slide with a red cross – the flag of St George and England’s national flag – and placed it atop the images, making the colonial context of the scenes apparent. He began employing the glass device over other images from his collection of photo books.

“I enjoy the fact that the device is glass because it feels as if,” Tariq says, “without any image behind it, it’s depicting the fragility of nationalism, how it can just shatter. The times this symbol has been adopted by the far right and by English nationalists and white supremacists is such a fragile patriotism because they’re kind of calling for things that are their own demise.”

100 Glass Cruciforms also highlights the fragility of a the national identity of England itself when one considers that St George, whose flag England has adopted, never set foot in England himself and was in fact a Cappadocian (modern day Turkey) Greek soldier, who is highly venerated both in the Levant’s (Palestine, Syria and Lebanon) Christian communities and in Islam.

And Tariq’s glass ‘cruciform’ is also a device which makes manifest the colonial question of photography which, as a practice, was developed in large to document and categorise indigenous populations in European colonies around the Global South. Images which were then, and still are to a large extent, housed behind glass panels, cases and vitrines in the West’s major art galleries, which often have historic imperial or defense-industry ties themselves such as the British Museum or the Victoria and Albert Museum, both in London.

In one black-and-white living room scene, we see children playing with each other using a gun; titled by Tarq as ‘Colonial Play’, the image was shot by Judah Passow and depicts Palestinian children reenacting the Intifadah in Fahme Village, west of Jenin, Palestine in the 80s. Another image by Zineke Diikstra shows a high schooler in Liverpool, England, with the flag set over his eyes. “There’s always a little bit of some tension between the image and the symbol. It’s very often that nationalist movements are heavily youth-led. Especially by young men and boys. So putting this symbol over his eyes speaks to how Europe had the Nazi youth or, in this country, we have a lot of white supremacist groups who are recruiting children,” Tariq explains, interrogating the ways in which children are implicated in global, neo-colonial conflicts in which Britain is implicated.

Elsewhere, the images are more explicitly violent and the link between British imperialism and global conflict, such as the ‘war on terror’, is clearer, an ideology which Tariq tells me catalysed his research. “I remember seeing this as a child. In one form or another, we all experienced [the ‘war on terror’]. I grew up in Saudi,” Tariq says, “and it was very present in the discourse there. People would always be talking about what was happening in Iraq or in Afghanistan. In the UK, when we had the Trojan horse affair, I remember being in school and being terrified that I was going to get falsely accused by the secret services. That fear as a child is the key starting point for my research and the war in Iraq was part of my visual consciousness.” In a tableau, Tariq groups together four infamous photojournalistic images from the 2003 invasion of Iraq, all shot by different photographers, but all serving as disturbing reminders of the role images played to boost military morale and garner public approval for the invasion.

The artist not only uses images from popular media or photojournalism but also weaves in personal histories into the body of work to demonstrate how the personal is indeed political. Four images show the glass device pressed over seeds – Tariq describes receiving a jar of seeds from his grandfather – seeds from his village in Pakistan – with a story of how, as a child, his grandfather would work the land from sunset to sunrise, following a spiritual rhythm deeply connected to the earth. This agricultural and Islamically rooted life, centred on planting, harvesting, and selling crops, formed the foundation of his family’s lineage and spirit. Placing a flag over the seeds in his work symbolises the displacement his grandfather experienced when he left Pakistan to immigrate and the colonial propaganda that compelled his migration to the UK, where the violence of the National Front disrupted the lives of his grandparents and parents.

100 Glass Cruciforms was recently on display at South Asia Archive’s pop-up at the Serpentine Gallery on 12 July, 2025. The images were shown in Tariq’s family album – he removed his family’s images and placed the ‘cruciform’ images inside in their place. Tariq is still developing the body of work and research whilst also working on an ongoing project about the muslim woman’s veil – it’s an idea Tariq has been thinking about for some time and is exploring through many mediums, experimenting with sculpture, image and textiles to unfurl the marginalised women at the heart of liberation movements and nation building efforts. “There’s no room for ego or for it to be about myself,” says Tariq of the project. “In the discussion of the veil, both extremes – to lose the veil or to enforce it – are about destroying the agency of the women who are wearing it.”