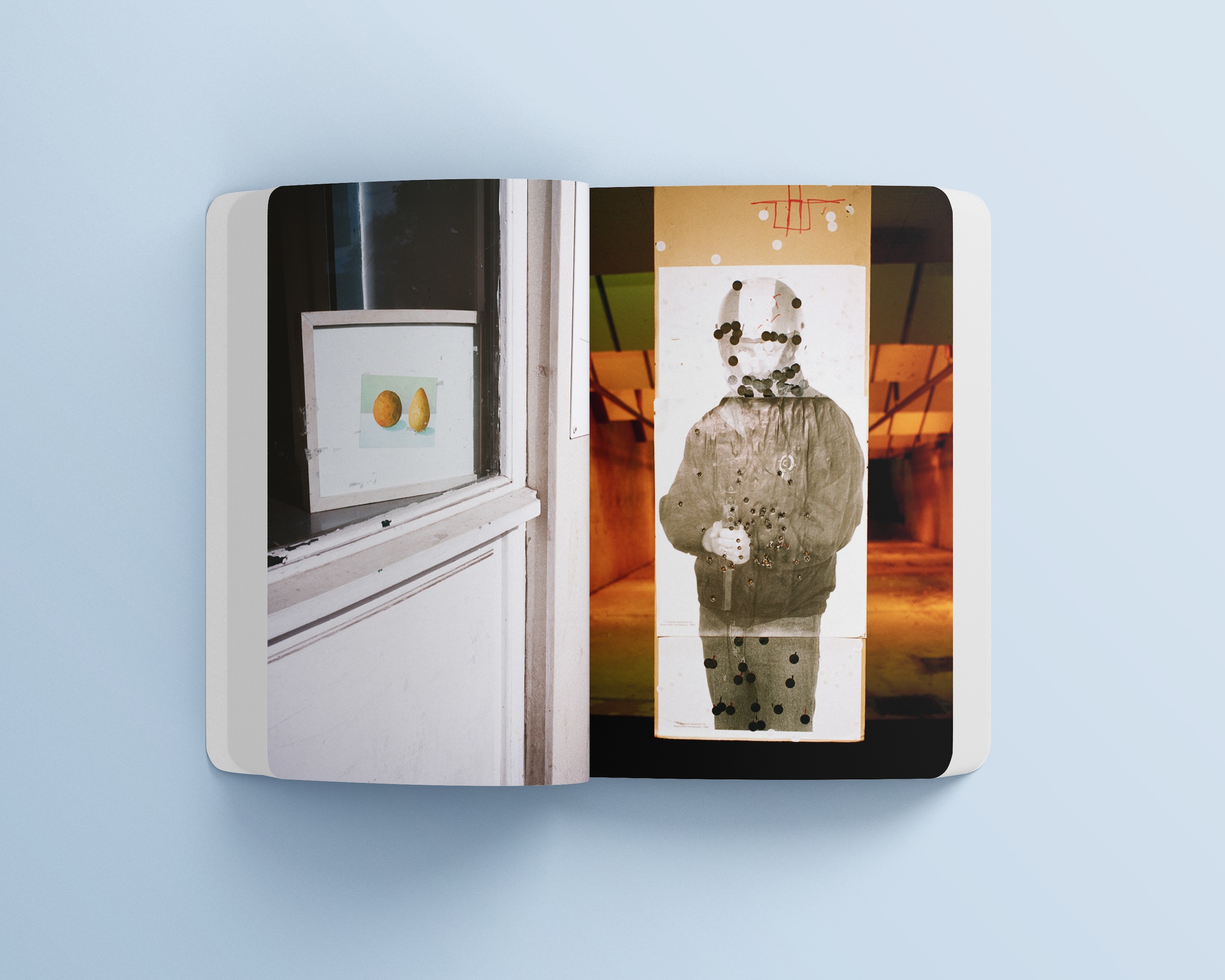

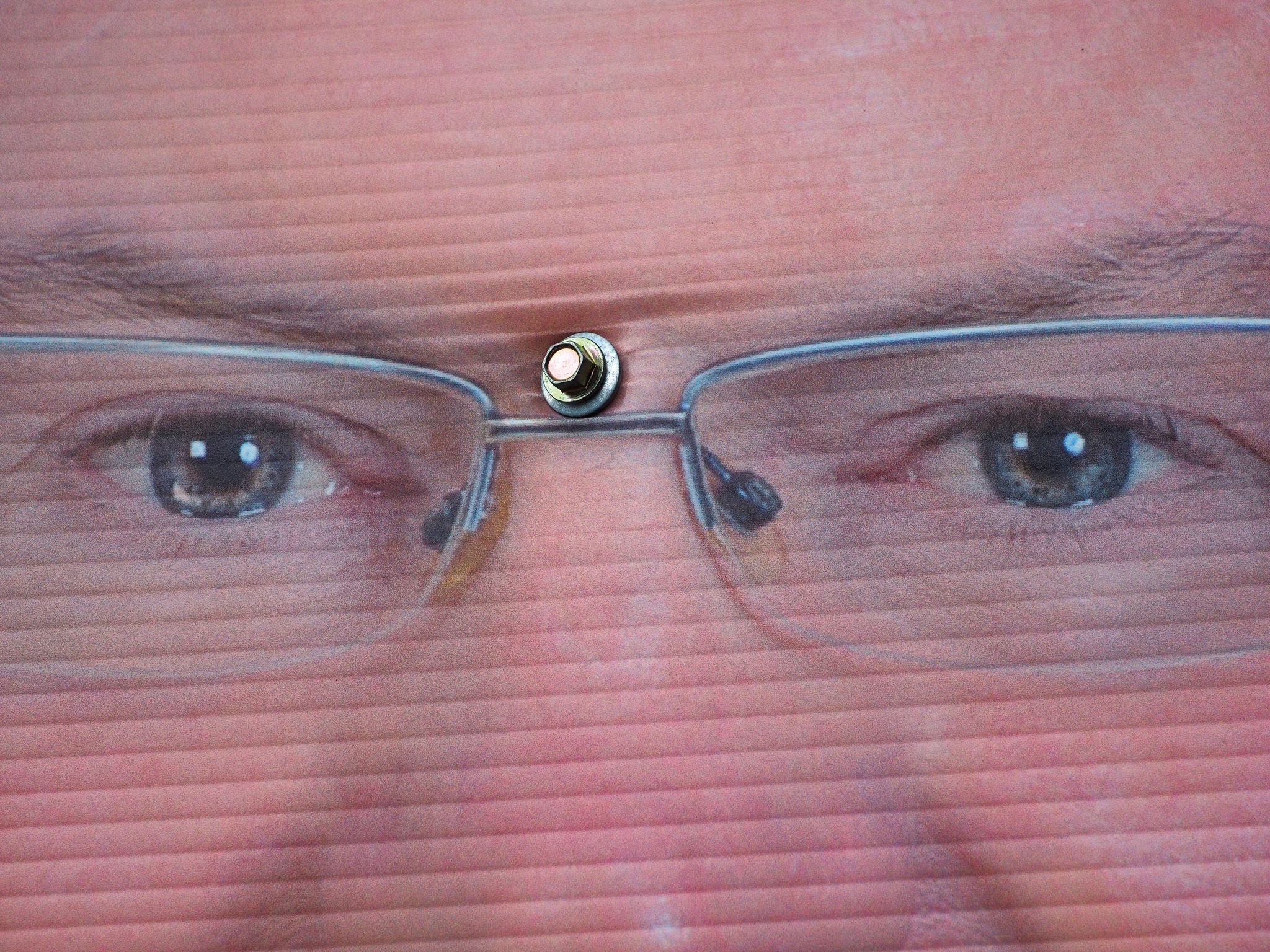

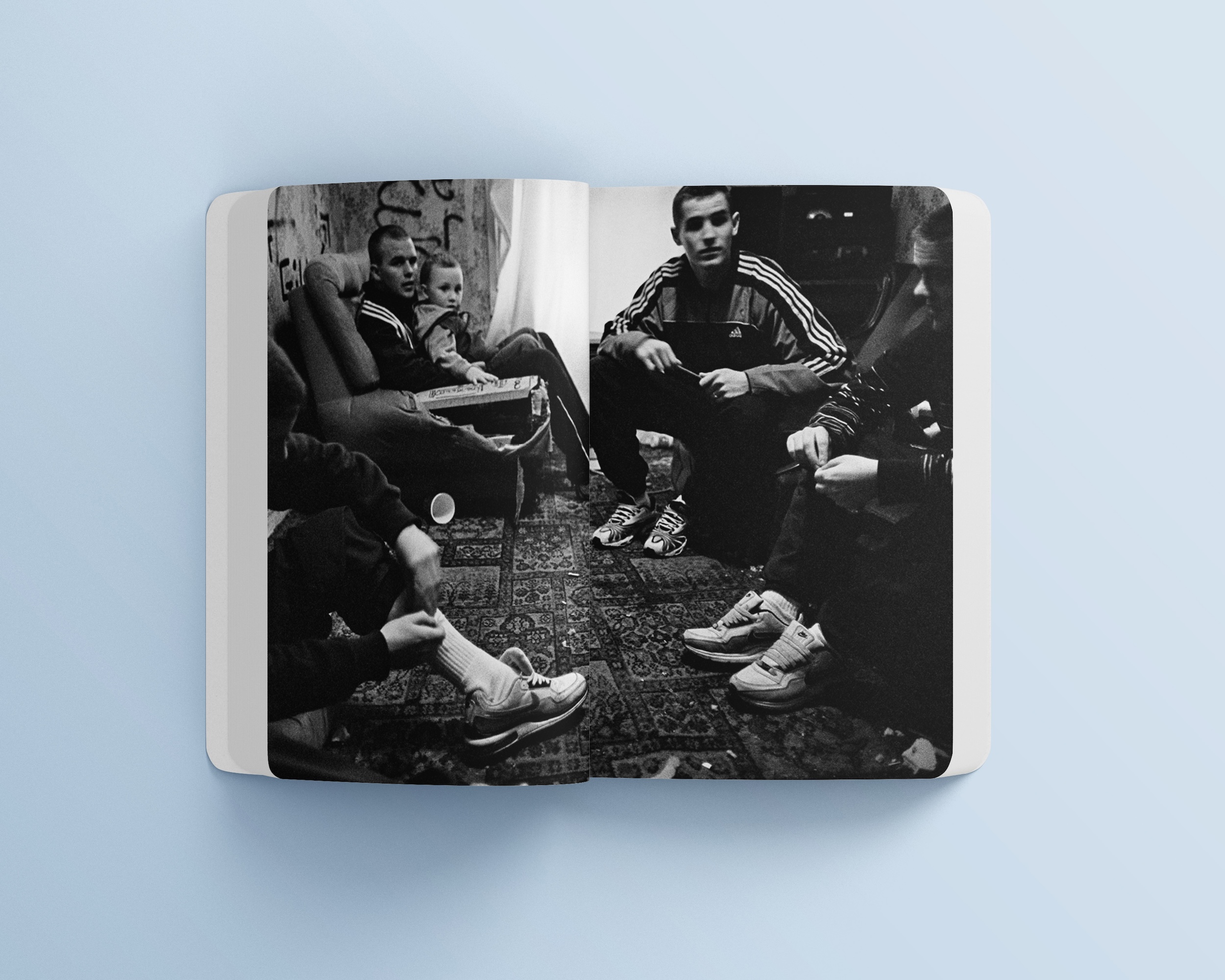

All images courtesy of Rotten Books

Fantasy Island is a collective publication from both Northern Ireland and the Republic that addresses some of the longest persisting ideas around the nation

Since the early 19th century, photography has played a crucial role in portraying Irish life – capturing both the turbulence of conflict and the contrasting aesthetics of rural idylls and industrial sprawl. The Troubles, in particular, have profoundly influenced how Ireland has been visually represented, often drawing external gazes into the narrative of national identity. From Japanese photographer Akihiko Okamura to British photojournalist Chris Steele-Perkins, outside perspectives have contributed to a fixed image of Ireland as a divided land marked by annihilation and stasis. This perception was further reinforced by the 2008 financial crash, which exposed the fragility of Ireland’s economy – especially its dependence on the real estate market – leading to widespread unemployment, austerity, and renewed waves of emigration.

Against this backdrop, Belfast-based publisher Rotten Books (Joel Seawright and Lucy Jackson) began researching existing compilations of Irish photography. What they found was a surprising gap: a lack of comprehensive collections that brought together past and present voices from both Northern Ireland and the Republic. To address this, Rotten Books has released Fantasy Island, a collective photo book designed to spark intergenerational dialogue within the photographic community and beyond. The project seeks not just to reflect on Irish identity, but to rethink and reconstruct it for the present moment.

“There is more to our history and culture than violence”

Through a fluid and intuitive editorial process, a pattern of recurring motifs begins to emerge: police, dogs, murals, bonfires, tracksuits, burnt-out cars. These images form a layered narrative, one that weaves together politics, place, and personal experience. As Jackson explains, the sequencing arose organically, connecting works across decades through shared visual cues and thematic resonance.

Megan Doherty’s photographs are emblematic of this approach. Shot during the making of her first series Stoned in Melanchol, her work documents the people in her life during the late 2010s while striving to uncover beauty in the mundane. “Shooting Stoned in Melanchol was a form of escape,” she says. “I was projecting my own visions onto the landscape of small-town life in an attempt to make my fantasy world a reality. But the more I photographed, the more the work naturally became about the people around me.” Her images capture the highs and lows of youth in post-crisis Ireland – offering intimate insight into a generation negotiating resilience, fragility, and the fallout of economic precarity.

A similar sensitivity is present in Gerry Balfe Smyth’s Last Breath, a series chronicling life in Dublin’s South Inner City, specifically the St. Teresa’s Gardens housing complex in The Liberties. Once a vast public housing estate built in the 1950s, the area had long suffered from neglect. Smyth embedded himself in the community over the course of seven years, building trust and gathering stories through his lens. “When I look at the pictures today, I remember the people fondly,” he reflects. “They allowed me access to their lives. I wanted the images to offer dignity and to spotlight the need for greater investment in working-class communities.” Though much of the complex has since been demolished and many residents relocated, Smyth’s photographs remain a poignant record of a place and its enduring challenges – ones that, sadly, persist today.

Throughout Fantasy Island, Seawright and Jackson were mindful to avoid letting the Troubles dominate the narrative. “There is more to our history and culture than violence,” Seawright notes. “But even when not overtly political, Irish photography is inevitably shaped by its context.” In the 1970s and 1980s, photography was a tool for processing conflict – an act of visual bearing witness. That impulse to understand one’s environment still resonates today, influencing how the current generation approaches image-making. For young photographers trying to reclaim and redefine Irishness, engaging with the past is less about nostalgia and more about rewriting the script. It’s a form of co-authorship – collaboratively narrating history from an inclusive, plural perspective.