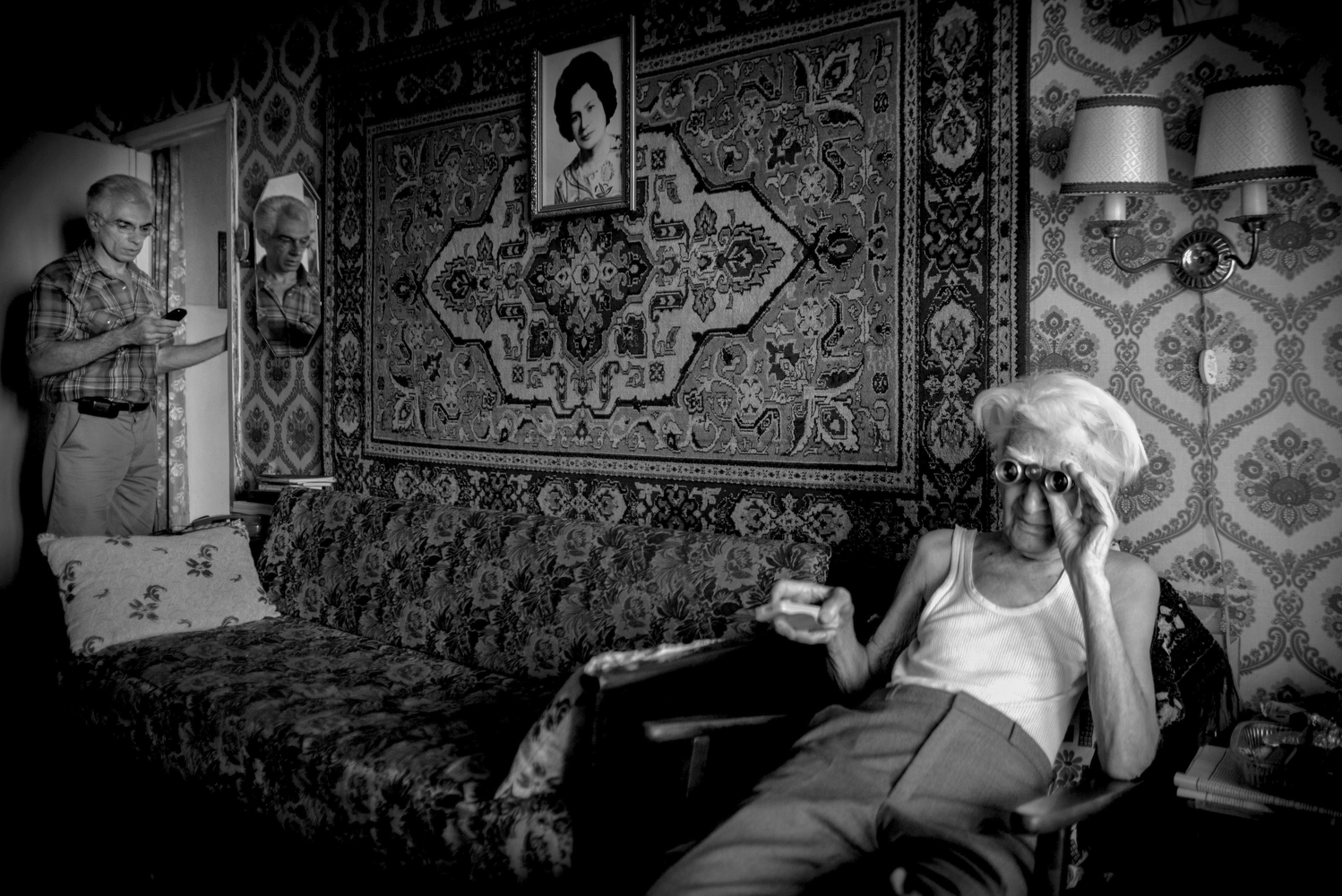

My grandfather’s suitcase filled with undelivered letters, a newspaper clipping and a shirt for my brother’s wedding. Anything to hold on to us. All images © Diana Markosian.

After publishing Father with Aperture and exhibitions at The National Portrait Gallery and Foam, the Armenian American photographer looks ahead to her shows in Berlin and at Les Recontres D’Arles

“We’re creating space for people to feel okay with not feeling okay,” Diana Markosian tells me, “and I think that space is so important.” We’re speaking about her latest exhibition at Foam, Father, off the back of her second photobook of the same name. Markosian knows a lot about holding space for complex feelings; her first monograph, Santa Barbara (also published by Aperture) explores Markosian’s journey to the United States as a young child alongside her brother and her mother. The book predominantly focuses on her mother’s story and her feelings, whilst Father (unsurprisingly) focuses on her second parent.

Markosian became estranged from her father from a young age. Born in Moscow, Russia, she was taken to California at the age of seven without saying goodbye to her father – both parents are Armenian, and her dad has remained there since they left, searching for the Markosian children who became missing. Her father and grandfather wrote hundreds of letters to government organisations, toy stores and random American addresses, in search of the family.

Once in California her mother erased the image of Markosian’s father by cutting his picture out of family photographs, one of which became the cover of the book. 15 years later, Markosian travelled back in search of him. “When I found my father I didn’t have a guide book and I wanted to create something that would help and inspire, and give someone else the strength that I needed to find my dad. I hope this book is a little bit of that.”

“I want you to really arrive right at the centre of the exhibition and understand that life is complicated”

Markosian, a contributor to Vanity Fair, Vogue and The New Yorker, first began Father years ago as she embarked on the journey to Armenia to find her dad. “I didn’t intend for this to be a project,” she explains. “I kept returning and I think photography gave me the courage to keep coming back. It just became this powerful weapon of courage that I was given.” Over a decade, from 2014 to 2024, she shot images that would eventually become Father.

But Markosian was also “getting to know him in a certain light,” a version of her father that she needed to exist in order to make not only the return journey and reconnection bearable, but make the images possible. Now, both Markosian and her father are hoping to get to know each other beyond the images. “Loving is growth, making another trip without making images is growth. Photography has been just supporting that growth, it hasn’t been leading it. Now, without photography,” continues Markosian, “I feel like we have another language to speak.”

The exhibition at Foam in Amsterdam is the first time the exhibition is shown in its entirety, displaying staged and vernacular images, family archives, and film. The exhibition’s tour began at the National Portrait Gallery in London with six almost life-size prints and after Foam the show will head to Arles before Fotografiska in Berlin. At each venue, visitors will have the opportunity to write a letter to someone they are estranged from, someone they have lost, or someone they simply miss and post the letter into a post box at the end of the show. It offers a way for visitors to engage and immerse themselves in Markosian’s story, transforming a personal narrative into a universal one and providing space for collective healing to ensue. It echoes the section at the back of the book which also provides an envelope and paper for a letter.

“The most beautiful part of the Foam show has been the letters,” Markosian tells me, showing me a video of the gallery team opening the post box with dozens of letters overflowing from it. “Just knowing that so many people feel they even want to sit and write.

“Every year I go back to Armenia and spend time with my father as a way of making up for that time that we didn’t have together,” she tells me. “There’s not enough years left, and that’s why I feel like I have to go back twice or three times because I just want more time with him.”

The exhibition brings the work to life in a way that feels “very raw,” continues the artist, “and I think the book is very intimate and contained and has its own story to it.” Upon reaching the end of the exhibition, we hear the voice of Markosian’s father through the film, which we aren’t able to hear – at least in a manifest way – through a book.

“I remember my dad even saying, ‘It took you so long to find me and you’re coming with so much blame. Don’t you want to hear my story?’ And I think this is the space that I wanted to create through this exhibit. I’ve presented my mother’s side and I’ve presented my father’s side. And I want you to believe my father and my mother. And I want you to really arrive right at the center of it and understand that life is complicated. And having empathy for both parents is my hope, as a daughter”.

Today, Markosian is wondering if her relationship with her father can evolve into something joyful, but that’s a brave step to take. “The art was made through the lens of a person I didn’t know and I was getting to know. And now that I know him, my father is asking me to start seeing him from a different point of view today”. It’s clear Markosian is curious about feelings surrounding shame, what is hidden, and the idea of vulnerability and emotional bravery. The artist is currently collaborating with an architect and priest to create a confession booth as a way of exploring themes of grief and trauma, , whilst looking ahead to another opening of Father at Recontres D’Arles this year in an excitingly expansive space and immersive format.