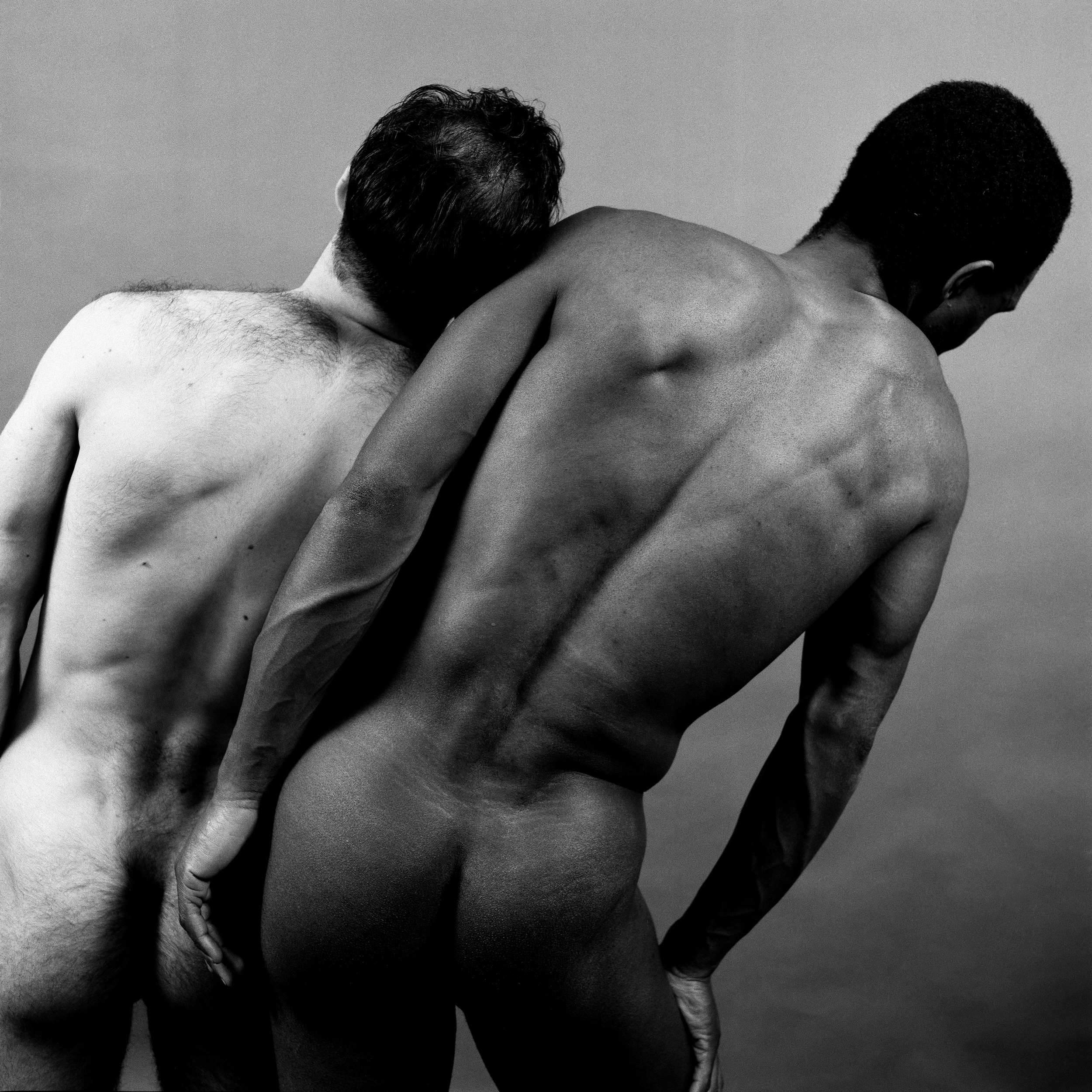

© Rotimi Fani-Kayode

The Studio — Staging Desire at Autograph Gallery explores the late Nigerian photographer’s practice centred around queer expression

Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s studio on Railton Road in Brixton was a frontline space in the 1980s: highly policed, it was the centre of riots and conflict — home to members of the Brixton Black Panthers; the Race Today collective; Marxist writer CLR James, as well as the South London Gay Community Centre and the Brixton Fairies. As the far-right gained ground under Thatcher, using the AIDs pandemic to justify their homophobia and racist sus laws to stop and search who they pleased; Fani-Kayode’s bright flat in the Brixton Housing co-op became a much-needed safe space for queer and Black individuals to express their desires and selves freely.

With light flooding in from his bay window, Fani-Kayode staged sculptural black and white photographs of his community: friends, colleagues and supporters. “They’re people who support each other during the day, they’re people that reinvent themselves at night,” says Mark Sealy, who has curated an exhibition of the artist’s work from that period, The Studio — Staging Desire, at Autograph gallery. In images of bleached blonde twins; muscled torsos and broad backs, Black men photographed in leather trousers and bondage and interracial couples hugging tenderly. “He’s working through what he called these traces of ecstasy,” says Sealy, “trying to create something really pleasurable, but at the same time mildly or deeply problematic and emotional.”

“Fani-Kayode is trying to talk about what he clearly says is entanglement and desire and the confusions of relationships that are enmeshed or immersed around the Black body”

Born in post-colonial Lagos in 1955, Fani-Kayode’s family fled the Nigerian civil war for the UK in 1966 — where he came of age in Brighton, before a brief stint in America where he was exposed to queer life and activism. In the United States, he completed a BA in fine arts and economics at Georgetown University, an MFA in photography at Pratt, then studied under the American photographer Robert Mapplethorpe. There are similarities in the style of their imagery but Mapplethorpe was more phallocentric, looking at the male form in an observational way rather than from a place of internal struggle, says Sealy. “Fani-Kayode is trying to talk about what he clearly says is entanglement and desire and the confusions of relationships that are enmeshed or immersed around the Black body.”

Throughout his brief career, which was cut short by his early death from AIDS at 34, the artist looked to the Eurocentric art historical canon as much as the Yoruba cosmology he learnt about from his Nigerian parents. In doing so, he tried to dismantle the hegemonic white gay narrative, while breaking some of the taboos around homosexuality in African culture. “This is someone operating on what I would call a kind of dial of difference,” says Sealy. “There’s a degree of trying to resolve something.” But, adds the curator, there’s also “this idea of pain and intimacy runs through the body of work.”

“What a lot of people don’t realise is that back then in the eighties, the idea of the black male nude was controversial – taboo even,” says Fani-Kayode’s friend and model, Dennis Carney, who first met the artist at a Black gay club in Soho called Stallions in 1985 or 86. “[Fani-Kayode] was in this club in a black leather jacket, black leather trousers, and dreads. At that time you didn’t really see a lot of black men walking the streets of London in full black leather. And he had the most beautiful dreads I’ve ever seen.” There was always a huge amount of laughter between the friends: “he didn’t take himself too seriously – he was playful.”

When it comes to photographers “bringing ideas of identity, desire and black body representation,” says Sealy, “Fani-Kayode is probably one of the most important artists working in Britain at that time.” Carney adds, “Fani-Kayode may have been a victim of the racism that existed in the field of photography at that time and it was a struggle for him to get his work out there because of that. But he succeeded to a large degree. He was making progress even with all of those challenges and struggles.”

His work has had a wide-reaching impact on artists globally today: when Fani-Kayode’s photographs were shown at Stevenson Gallery in the early 2000s, South African artist Zanele Muhuli was hugely influenced by this work. The same is true of the American photographer Paul Sepuya, whose intimate studio portraits explore the relationships between camera, subject and viewer; Ghanaian photographer Eric Gyamfi, who looks at queer life in Accra, and the British artist, curator, archivist and activist Ajamu, best known for his fine art photographs of same-sex desire and the Black male body. “I would argue that without Fani-Kayode, this sense of lineage of work in the field of queer dynamics isn’t possible,” says Sealy.