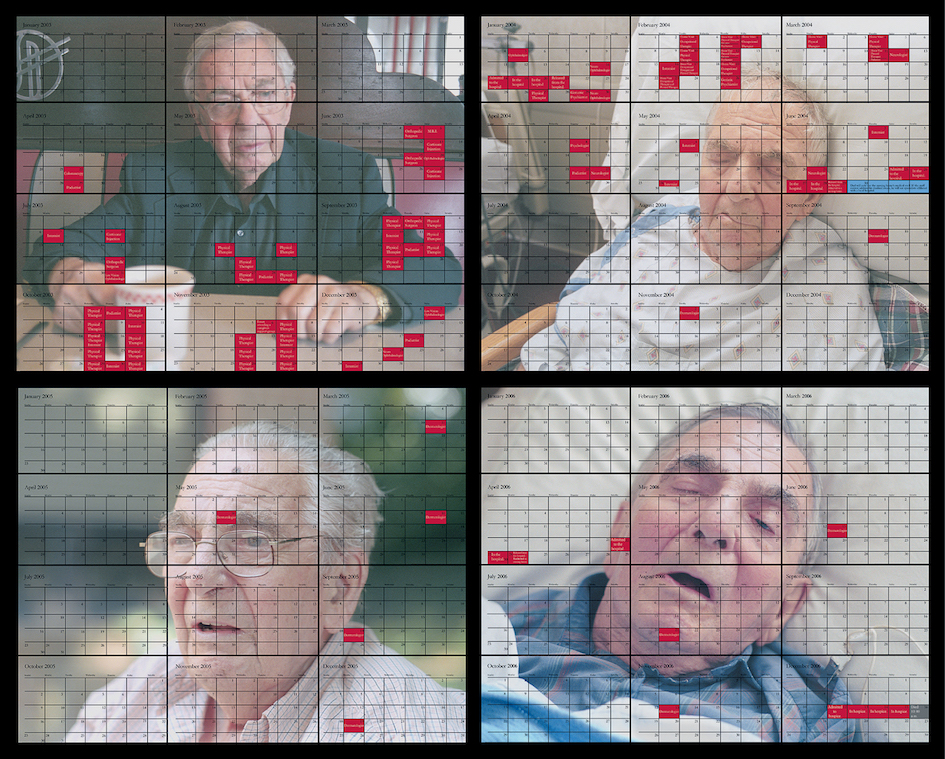

Gail Rebhan, Medical Appointments II. Courtesy the artist and MACK

The Chicago-born artist uses image and text compositions to make sense of the world around her, from picket lines and news adverts to her father’s declining health

During a lecture he delivered in Baltimore in 1984, Roy DeCarava, the renowned photographer who worked alongside legendary jazz musicians, allowed himself his own improvisational flourish. In the audience was fledgling photographer Gail Rebhan, along with her husband, Mark and newborn son, Andy. When Andy began to cry, Mark took the responsibility of standing up to carry him outside. Instead of ignoring the interruption, DeCarava incorporated it into his flow. “This connoisseur of jazz commented extemporaneously that a baby’s cry was one of the sweetest sounds,” recounts Sally Stein. In other words, DeCarava didn’t allow this detail to escape the frame.

Extemporaneous detail, the activating beauty of chance, was as important to DeCarava’s work as it was to the musicians he photographed. The critic Geoff Dyer names DeCarava’s fuzzy photo of a young John Coltrane in a candid moment with Ben Webster as “the central photograph in jazz,” precisely because of the “technical failing” of its snapshot-blur. It “succeeds in allowing more time to leak into and spill over from the picture…as if everything around it has been eaten by time,” he writes. For DeCarava, the inability of a single frame to capture sound and movement becomes the best possible communicator of the present, the local time of the music and the historic time of the age ticker-taping out from either side of the picture.

“The role of the camera as a means of bearing witness to ‘big time’ historic reportage informs the beginnings of her practice, even while capturing the ‘small time’ of domestic interiors”

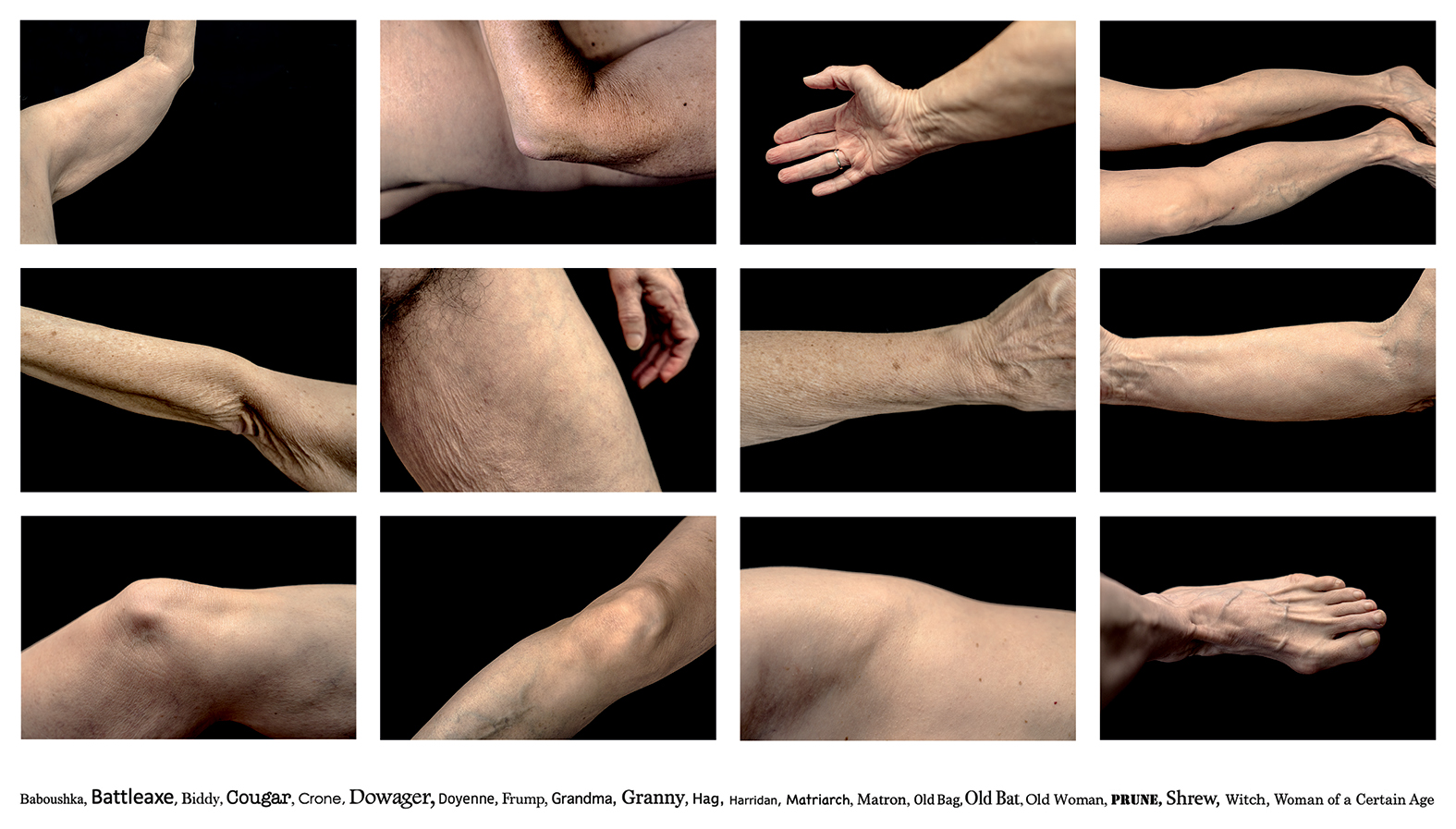

The first intention of About Time, the first retrospective of Gail Rebhan’s photographs, is to situate her work within the context of these conversations about photography and time. It collects four decades of photographic series, ranging from the 1980s domestic scenes to the stark beauty of nude self-portraits from 2022.

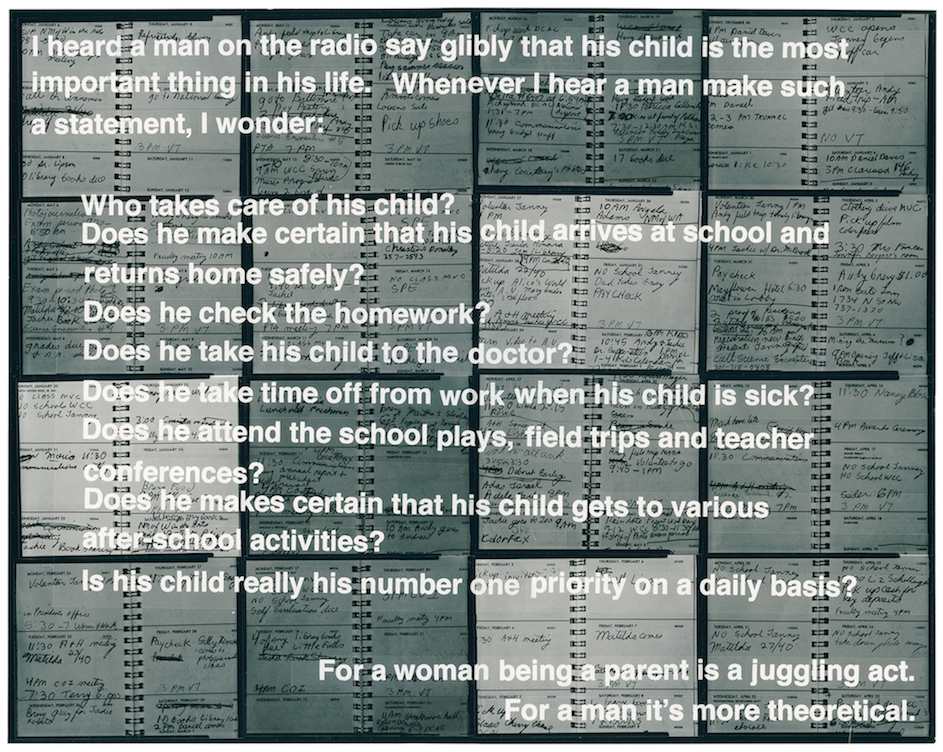

Rebhan’s work, as much as DeCarava’s, is “about time” in that it takes durational change (micro and macro) as its central theme. But, as Stein insists, it’s also “about time” we acknowledged Rebhan’s work as a counterpoint to someone like DeCarava; about time the cloud of men and theory made way for Rebhan’s focus on the quotidian truths behind that ‘child’s cry’ to which the elder male artist responded. Rebhan’s work shows that this cry is part of a complex language of labour (crucially the unpaid labour foisted upon women), relationships, images, objects, and temporal selfhood which informs both its momentary expressiveness and its grander importance.

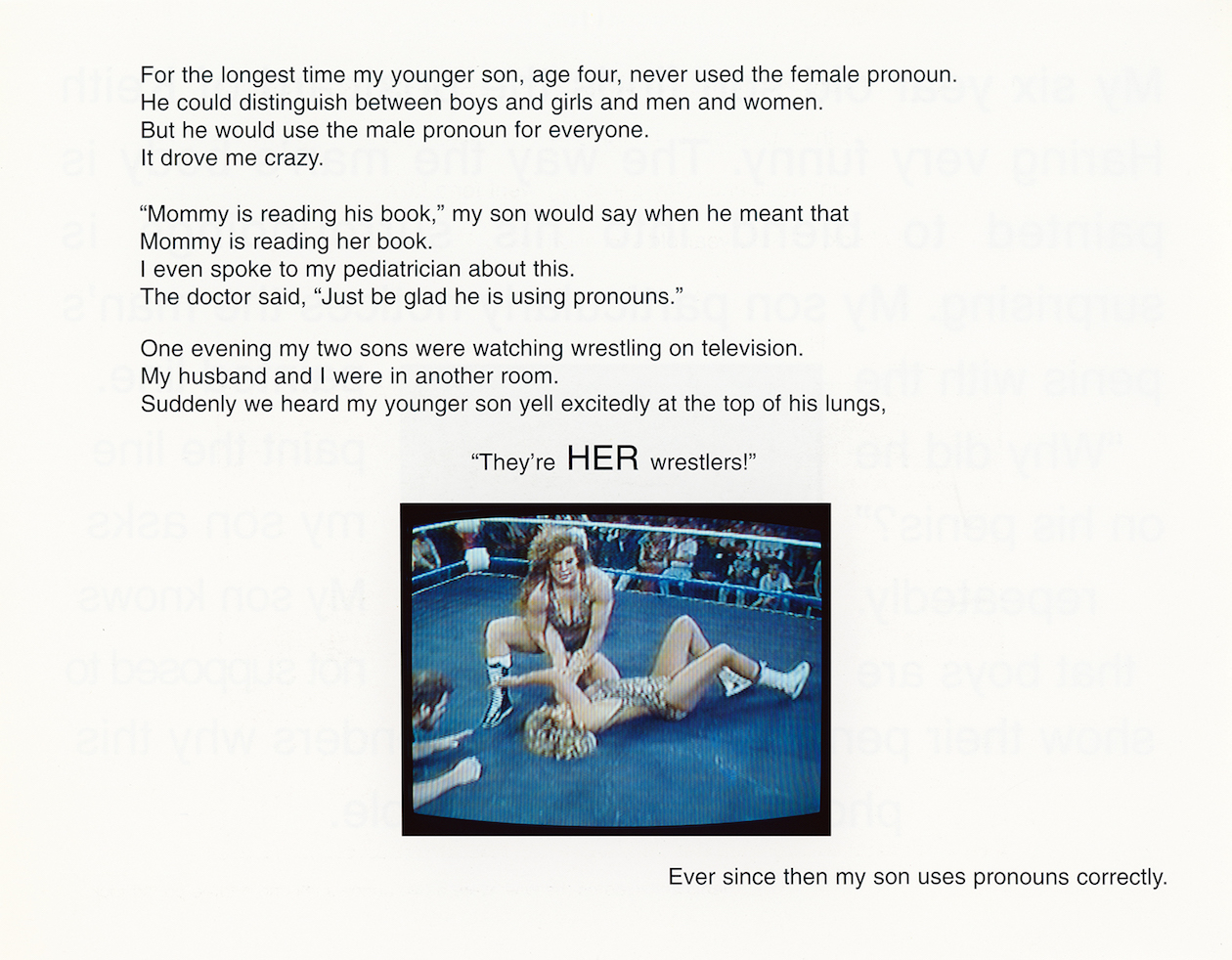

A photography that communicates all this would need to display both split-second dynamism and narrative power. At times, Rebhan goes literal. The extreme-close-up portraits of crying infants show a mother’s-eye view that shocked male viewers when they were first exhibited on a huge scale in 1986. 280 Days finds the Chicago-born artist stealing odd moments to photograph herself in a closet mirror daily throughout her first pregnancy. For the most part, Rebhan’s early work achieves the feat by bringing ‘the snapshot’ indoors.

The daughter of a labour-movement leader with an international reputation, Rebhan honed her eye with journalistic snaps of marches and picket lines. About Time reproduces her cover for a 1981 steel-workers’ magazine, a forest of sloganed signs leading away into the distance where the Capitol Building looms.

The role of the camera as a means of bearing witness to ‘big time’ historic reportage informs the beginnings of her practice, even while capturing the ‘small time’ of domestic interiors. Her husband Mark throws a toy for a cat, which is caught suspended in mid-air. A friend shows holiday slides. Mark’s ailing mother serves tea, despite her infirmity. History seeps in through a frame-inside-the-frame – the household’s small TV. ‘Big’ and ‘small’ time seem to trade places. A documentary impulse meets the artist’s feel for human character.

In photographs of Mark being shown holiday-sides by his eager friend, Rebhan looks at these lookers, picking out their eyeline and, in turn, meditating on the act itself. The composition raises further questions. Who gets to do the looking? Is ‘looking’ simply recreational, or can it be a form of creative labour? Rebhan has also learned from DeCarava the trick of marrying a dispassionate eye (which allows the photos to feel candid) with a creative framing-act (which communicates the photographer’s own subjectivity, making the photos feel like ‘art’). Life, it seems, is always larger-than-life.

By the 1990s, Rebhan’s work had become more like collage, inundated with the Age of Information and a little unsure what to make of it. The series Mother-Son Talk (1996) will strike contemporary viewers, reared on memes, as glib and on-the-nose. One collage offsets a map of the District of Columbia’s population distribution with the exchange, “Son (age eight): “Why do only black people live in this neighbourhood? What do they have? A sign that says Blacks Welcome?” Mom: “Well, there are lots of reasons why neighbourhoods are composed the way they are.”

Again, the quotidian-domestic collides with larger histories, but absent is evidence of Rebhan’s image-making instincts. The artist retains the dispassion, presenting evidence and allowing it to speak for itself, but here misses the observational genius and emotional impact of, say Anna Fox’s series My Mother’s Cupboards and My Father’s Words (1999), a work that reveals the latent creativity in both acts of systematic domestic abuse and a victim’s response to them.

In the early 2000s, Rebhan made several series charting her father’s declining health and eventual death. A group of four portraits tracks his transition from sitting upright and alert in a coffee shop to supine in a sick-bed, mouth agape. Superimposed onto the faces are calendars showing four years of medical appointments. Time no longer surrounds the picture; the picture positions itself “about” time, encompassing it. It’s a noble act, heavy and moving in its failure to truly contain what it tries to.

If DeCarava’s dynamism made a lasting impression on Rebhan, it’s a decidedly more mute picture which she singles out as her favourite of his. ‘Window and Stove’, notable for being completely unpeopled, is a dusky black-and-white picture of a cooking pot in a tiny, dark kitchen. Visible through a window is a shadowy factory building with a water tank on the roof. Closer to the pane is an industrial winch, its cables streaming off to the right. The photo is taken in such a way as to line up these cables almost exactly with the jutting handle of the pot on the stove.

For Rebhan, the suggestion of winching some looming, labour-inflected weight into the frame, then rhyming it with a domestic interior, was a crucial influence. About Time is an important interjection, pulling Rebhan back into the frame of photographic history by showing what she could (and couldn’t) successfully pull into her own frames.

Gail Rebhan, About Time, is at the American University Museum, Washington, D.C., from 4 February until 21 May

About Time by Gail Rebhan, edited by Sally Stein, is out now (MACK)