All images © Ditte Haarløv Johnsen

Published by Disko Bay, the 25-year-long project sits at the intersection of resolution and conclusion with striking honesty

At first glance, Ditte Haarløv Johnsen’s debut photobook, Maputo Diary, is not easy to understand. The photographer’s role within the situations and scenes photographed seems to metamorphose with every page’s turn. That’s why, as Johnsen tells me, context here is important.

The diary entries at the beginning of the book read: “At the same time, the reality of not having a home or a family here anymore is alienating. Maputo feels different – more tense. I see myself walking its streets: a 45-year-old woman weighed down by heavy camera bags, too wary to stop and photograph.”

Elsewhere, in ‘Remembering’, she writes, “I grew up in the victorious atmosphere that reigned after Mozambique’s War of Independence. It was a time full of hope for the future, a new beginning for the country. From the roof of my local kindergarten, I would stand alongside my Mozambican friends with a clenched fist pointing to the sky shouting ‘Long live the Mozambican Revolution!” “Long live the Frelimo party!’”

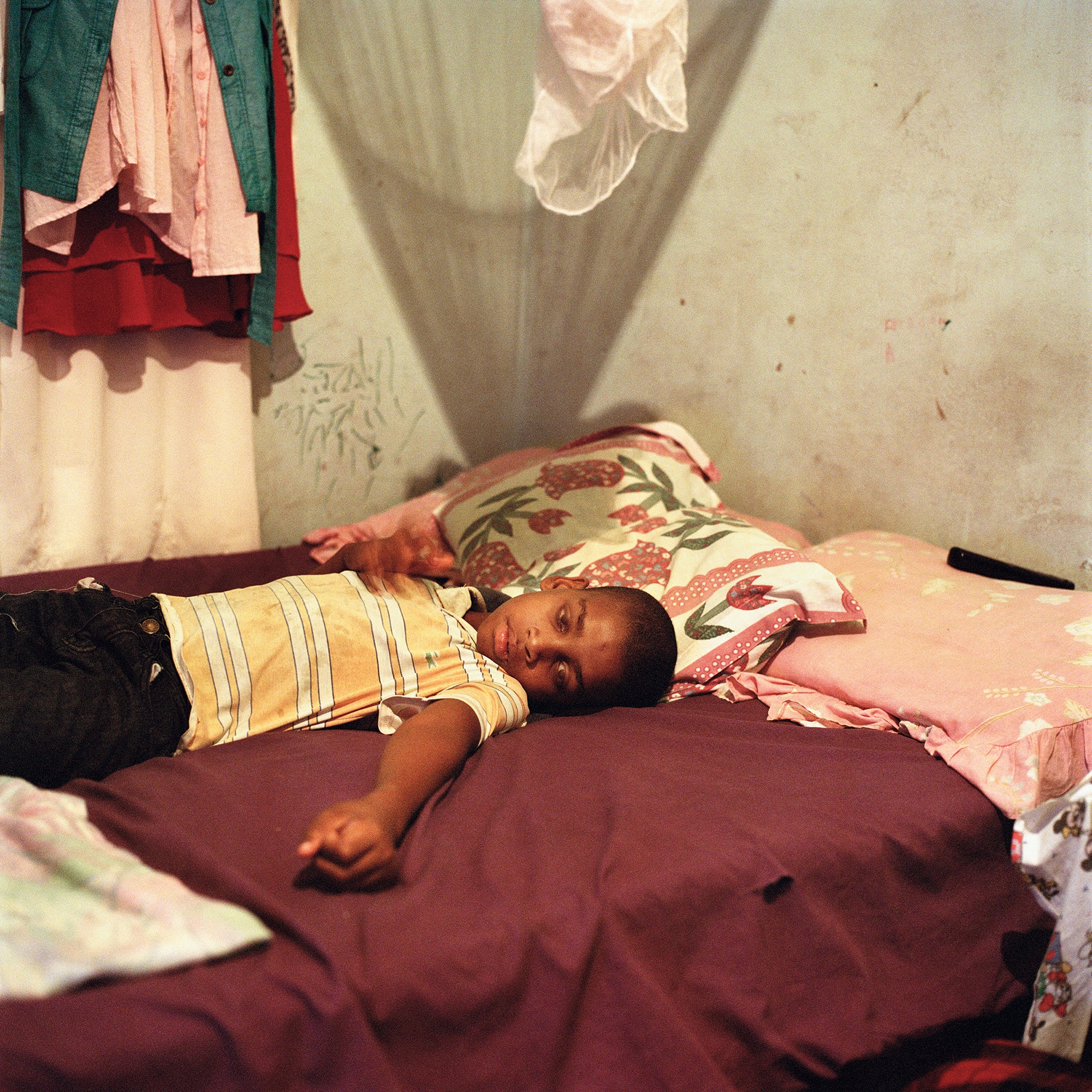

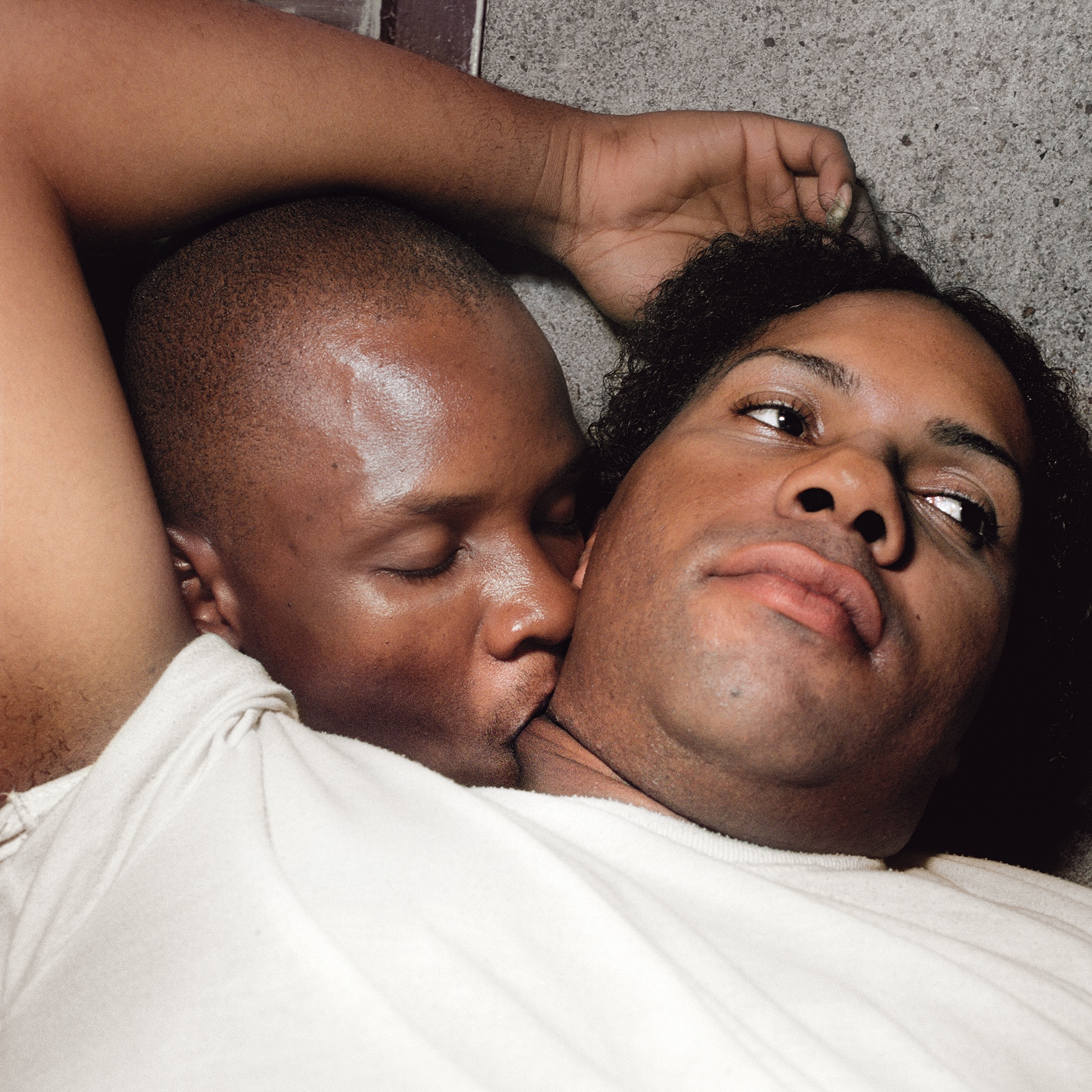

Johnsen grew up in Maputo, Mozambique, and as a young woman, she befriended the town’s transgender and queer community. Even before speaking to Johnsen, her intimacy with her subjects is clear to me. One tender close-up shot shows a trans woman flipping her wig upside down in order to fix it to her head. In another portrait, two friends – lovers – lay down in bed and embrace each other.

“Some stories can only unfold in their own time”

Maputo Diary spans a 25-year arc, beginning when Johnsen was in her early twenties and concluding only a few years ago, in 2022. During those years, the work was shown in different exhibitions, each functioning as a way for her to understand what the project was becoming. “The exhibitions were a way for me to understand the work’s own direction,” she explains, “to see which images spoke to one another and which questions they could raise together about what it means to be human.”

The book became “a natural continuation of the need to pay justice to the people portrayed and their stories,” she says, “and my own feeling of being so touched by life that I needed an outlet that was deeper than what framed images hanging on a gallery wall could convey.” Still, the book resisted being made. She produced multiple dummies over the years, none of which felt right. The material was too interconnected, too emotionally dense, and perhaps she herself was not yet able to see her own position within it.

The protagonists at the heart of her photos include Ingrácia, Yara and Antonieta. They make up a community of trans women that Johnsen formed a deep bond with during her time living in Maputo.

In the intervening years, Johnsen studied documentary filmmaking in Denmark and made films with protagonists she was equally deeply involved with. She spent years caring for her grandmother, while her mother remained in Mozambique. In between these responsibilities, she kept returning to Maputo – to visit her mother and sister, and to photograph. “Photographing felt like necessity, not choice,” she tells me. “I work very intuitively, and I simply kept going. The series grew. The story grew. And the more it grew, the more humbled I felt by this sense that the work had its own inner logic – something I couldn’t fully grasp.”

That sense of surrender to the project’s own timing runs through the book. “Working with Maputo Diary I’ve had to respect the inner timing of a story,” Johnsen says. “Some stories can only unfold in their own time.” Now, close to 50, she speaks with a clarity and humility she didn’t have at 23, when she first met Ingrácia and Antonieta – two of the central figures in the book. “I can finally see my own position in the story,” she says.

When she returned to Maputo in 2022, her intention was simply to make one last portrait of Ingrácia. Then Yara was murdered, and the project opened once more. “Another chapter opened – one I was obliged to follow,” she says. Those photographs became the final ones in the book. Ending the project, she explains, was not about resolution so much as responsibility and making peace with the efforts she had made toward the project. Life moves on, and she herself is in a different place now, especially after becoming a mother. “On a personal level, I needed to put a full stop to it– with the blessing of the people portrayed – so I could make space for other journeys.”

In the intervening years, Johnsen studied documentary filmmaking in Denmark and made films with protagonists she was equally deeply involved with. She spent years caring for her grandmother, while her mother remained in Mozambique. In between these responsibilities, she kept returning to Maputo – to visit her mother and sister, and to photograph. “Photographing felt like necessity, not choice,” she tells me. “I work very intuitively, and I simply kept going. The series grew. The story grew. And the more it grew, the more humbled I felt by this sense that the work had its own inner logic – something I couldn’t fully grasp.”

That sense of surrender to the project’s own timing runs through the book. “Working with Maputo Diary I’ve had to respect the inner timing of a story,” Johnsen says. “Some stories can only unfold in their own time.” Now, close to 50, she speaks with a clarity and humility she didn’t have at 23, when she first met Ingrácia and Antonieta – two of the central figures in the book. “I can finally see my own position in the story,” she says.

When she returned to Maputo in 2022, her intention was simply to make one last portrait of Ingrácia. Then Yara was murdered, and the project opened once more. “Another chapter opened – one I was obliged to follow,” she says. Those photographs became the final ones in the book. Ending the project, she explains, was not about resolution so much as responsibility and making peace with the efforts she had made toward the project. Life moves on, and she herself is in a different place now, especially after becoming a mother. “On a personal level, I needed to put a full stop to it, with the blessing of the people portrayed, so I could make space for other journeys.”

Writing the text that accompanies the images proved to be one of the most difficult parts of the process. Johnsen is clear that her upbringing informs everything she does. She remembers vividly the atmosphere of post-independence Mozambique, the sense of collective liberation that became, as she puts it, “a spiritual compass” for her. When her family arrived in Mozambique in 1982, the ANC’s struggle against apartheid was at its height. Friends of her parents were bombed or disappeared. Warplanes flew over her kindergarten. Civil war intensified, and violence became part of everyday life. “Nearly every friend had lost someone,” she recalls, “or knew of a cousin kidnapped to fight as a child soldier.” The war was everywhere, yet she also felt, paradoxically, shielded from it.

As well as unspoken taboos within her family which shaped her deeply, and she draws a direct line between it and her connection to Ingrácia and Antonieta. “They walked through the world with their taboo on the outside,” she says. Writing about this – about her family, about herself – was painful, but also necessary. “Saying a taboo out loud can offer a kind of freedom,” she reflects, “also to a potential reader.”

Throughout the writing process, Johnsen was in constant dialogue with the people portrayed in the book. She shared drafts, checked timelines, listened as the Manas corrected her memory and added their own voices. “Weaving their voices into my narrative required constant awareness of privilege,” she says, “and a careful navigation of the fine line between honesty and polarisation.” Writing, she admits, does not come easily to her, and balancing her own story with the stories of others – without erasing or dominating them – was extremely difficult.

Questions of privilege and positionality sit at the core of Maputo Diary. Johnsen is explicit about the fact that she is a white woman shaped by whiteness, photographing Black queer and trans bodies. The book does not attempt to dissolve this tension, but to sit with it. The relationships at its heart are not romanticised as equal, but neither are they reduced to a single axis of difference. Over time, the Manas became a chosen family for Johnsen, even as she remained conscious of the vast disparities in their starting points in life.

This is where the book resists easy categorisation within contemporary identity politics. Johnsen is careful to clarify that she does not oppose polarisation as such. “Polarisation can be a necessary tool for exposing deep systemic injustices,” she says, particularly in Europe, where colonial legacies and systemic racism remain unresolved. But polarisation, she insists, cannot be the goal. In a world marked by genocide, rising fascism, border fortification, and climate catastrophe, she argues that there is an urgent need to act across divides. “That’s where true hope resides.”

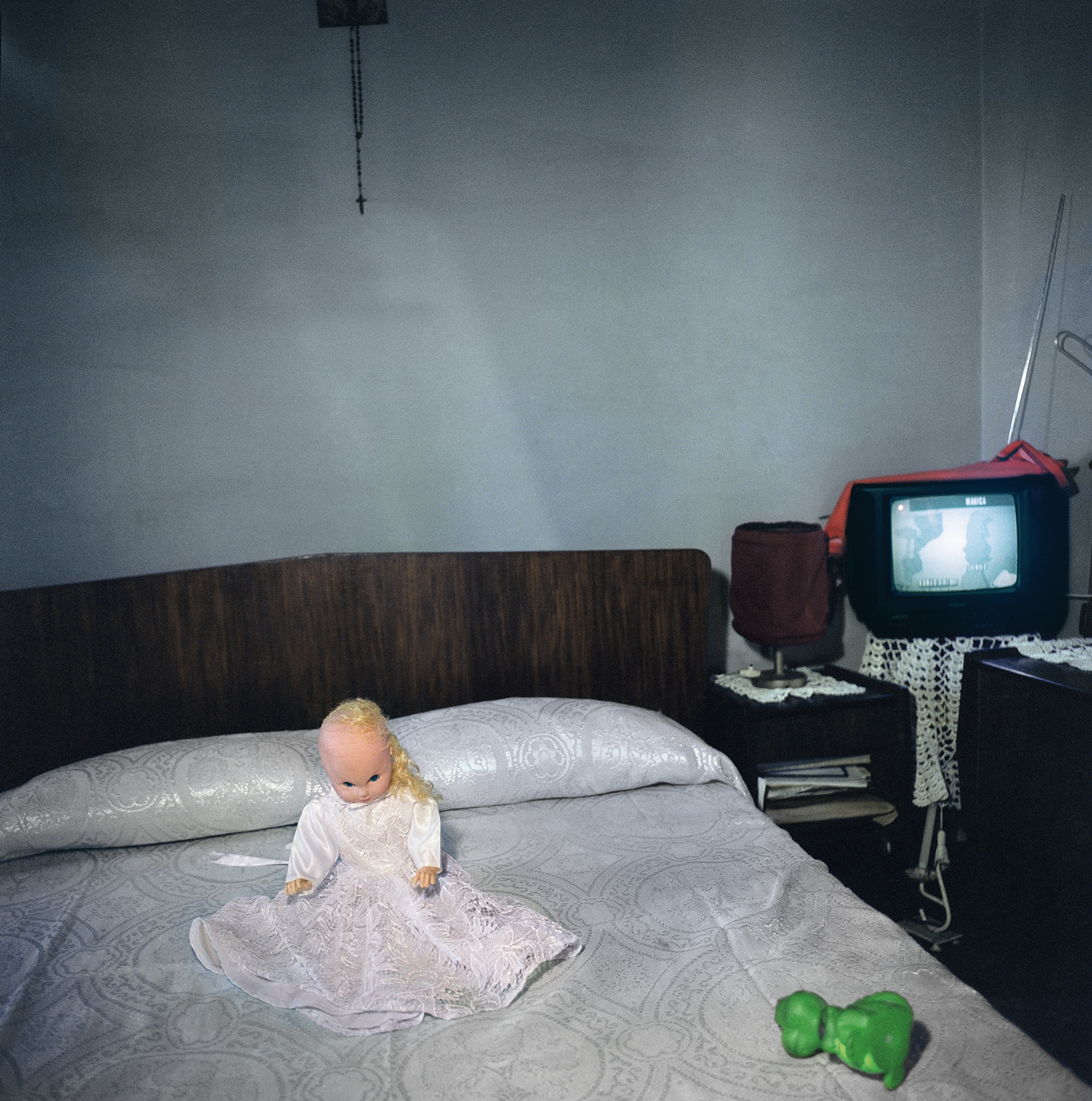

What she hopes Maputo Diary offers is nuance. Above all, she hopes the people in the book are honoured. “It’s also about the need for an archive,” she says. “To say: this is how it was. These people were here. Some of them still are. Let’s honour the fact that they existed, that they exist, and the connections between all of us.”