© Thato Toeba, Man on Fire, 2017. Courtesy the artist

I Still Dream of Lost Vocabularies invites new perspectives on social histories through mixed-media image making, finds Phin Jennings

Sabrina Tirvengadum, a British Mauritian photographer, has seen very few images of her family history from before 1960. She knew that, in the 19th century, her Mauritian ancestors had been indentured labourers working for a wealthy family of sugar plantation owners, but was unsure of what their lives looked like. Working from a handful of photographs and her own imagination, she started experimenting with an AI model to create images of her family’s hidden history. A suite of these images is currently on show at Autograph as part of I Still Dream of Lost Vocabularies, a group exhibition curated by Bindi Vora, which opened 10 October, 2025. “It blends my own memories, what’s real and what I imagine. It mixes together pasts and reimagines history,” Tirvengadum tells me.

In each frame, contexts and figures blend together in strange ways, giving the impression of a vaguely-remembered dream. Happy Birthday to You (2025) shows a smartly-dressed family of eleven gathered around a table in the middle of a forest; in Pose for our Family (2025), a young woman grasps a teddy bear with no legs. Tirvengadum likes to keep the discontinuities and hallucinations that the AI model concocts, because they reflect the glitches in her own understanding of the past: “Something’s always not quite right, and histories are distorted in a way as well.”

Across the work of the thirteen artists in this exhibition – photography, painting, textiles, video and more brought together under an expanded understanding of collage – the questioning and augmenting of the historical canon and official archives is a running theme. Each artist cuts, sticks and edits images to capture various undocumented histories that are sometimes personal, sometimes political, and often both.

“The hidden narratives in these personal archives have been suppressed by larger institutional histories”

“I think we sometimes mistake what we’re seeing as a physical photograph for truth and for record,” Vora says. “With these artists, what you’re seeing them do is challenging the authority of that. And I think that calls into question the role of archives and collections.” Indeed, the idea of photographic truth and our understanding of a photograph as testimony are repeatedly tested in this exhibition. The idea that emerges is both frightening and exciting: what if the images on show here, manipulated using methods ranging from traditional cut-and-paste collage to generative AI, contain more truth than those in history books? “When I look at traditional photography, I don’t always see it as truth,” Tirvengadum tells me, “because it’s about perspective. And [my work] is my perspective.”

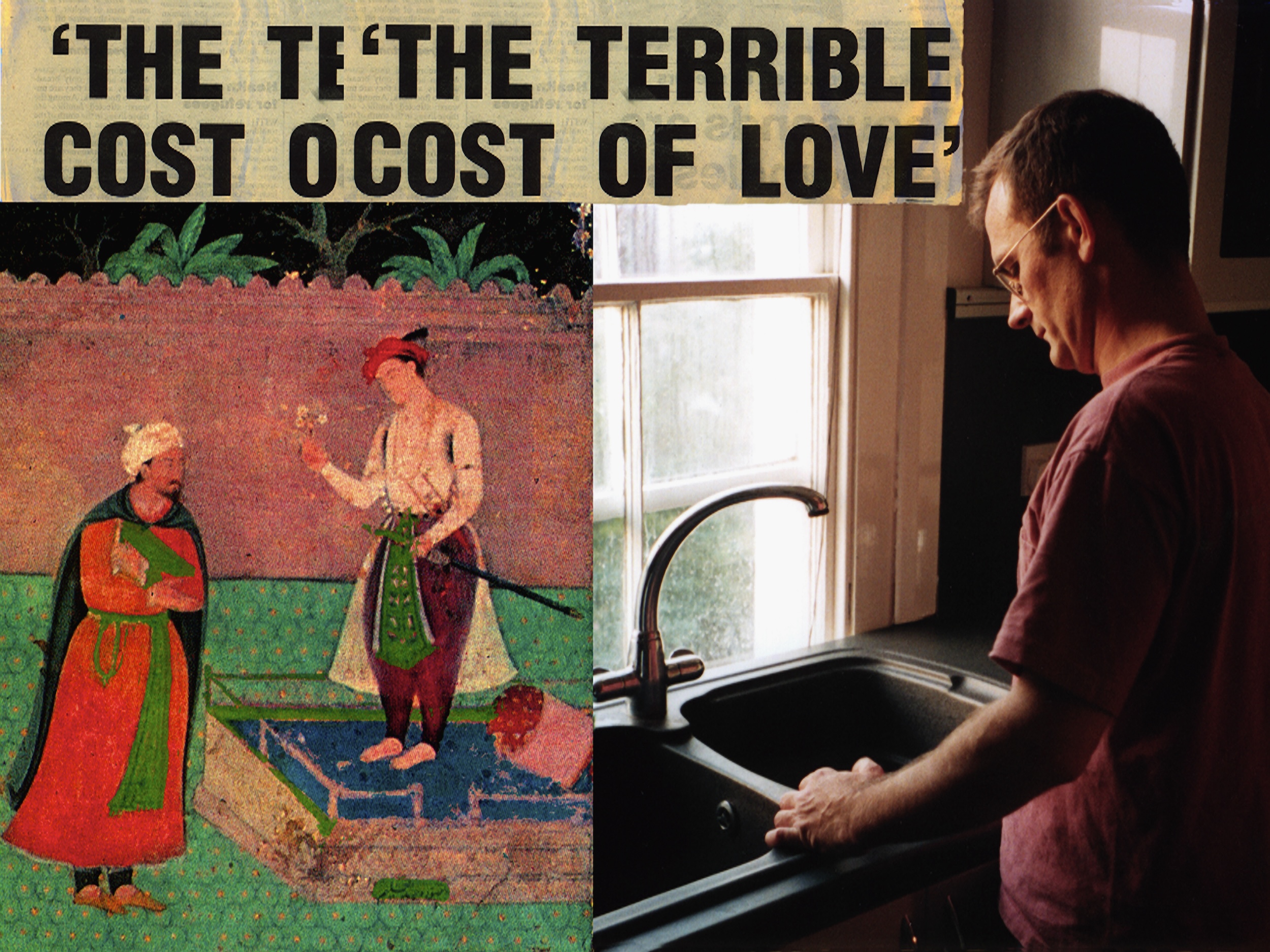

To wander through the show is to look at thirteen different places and moments from thirteen different perspectives. They come together, whether their subjects are familiar or not, to reaffirm how much of this world’s history is misunderstood, undocumented or both. There’s Wendimagegn Belete’s video work Unveil (2016), a composite portrait of hundreds of people involved in Ethiopia’s resistance to Benito Mussolini’s invasion in the 1930s, making Ethiopia the only African nation to successfully resist European colonisation. Elsewhere, Thato Toeba’s Man on Fire (2017), a photographic collage reproduced here as a large-scale wallpaper, refers to the story of Ernesto Alfabeto Nhamuave, a Mozambican man who was burned to death during a wave of xenophobic violence in Johannesburg in 2008. In both cases, where photographic records fall short, collage is a way to correct the archive.

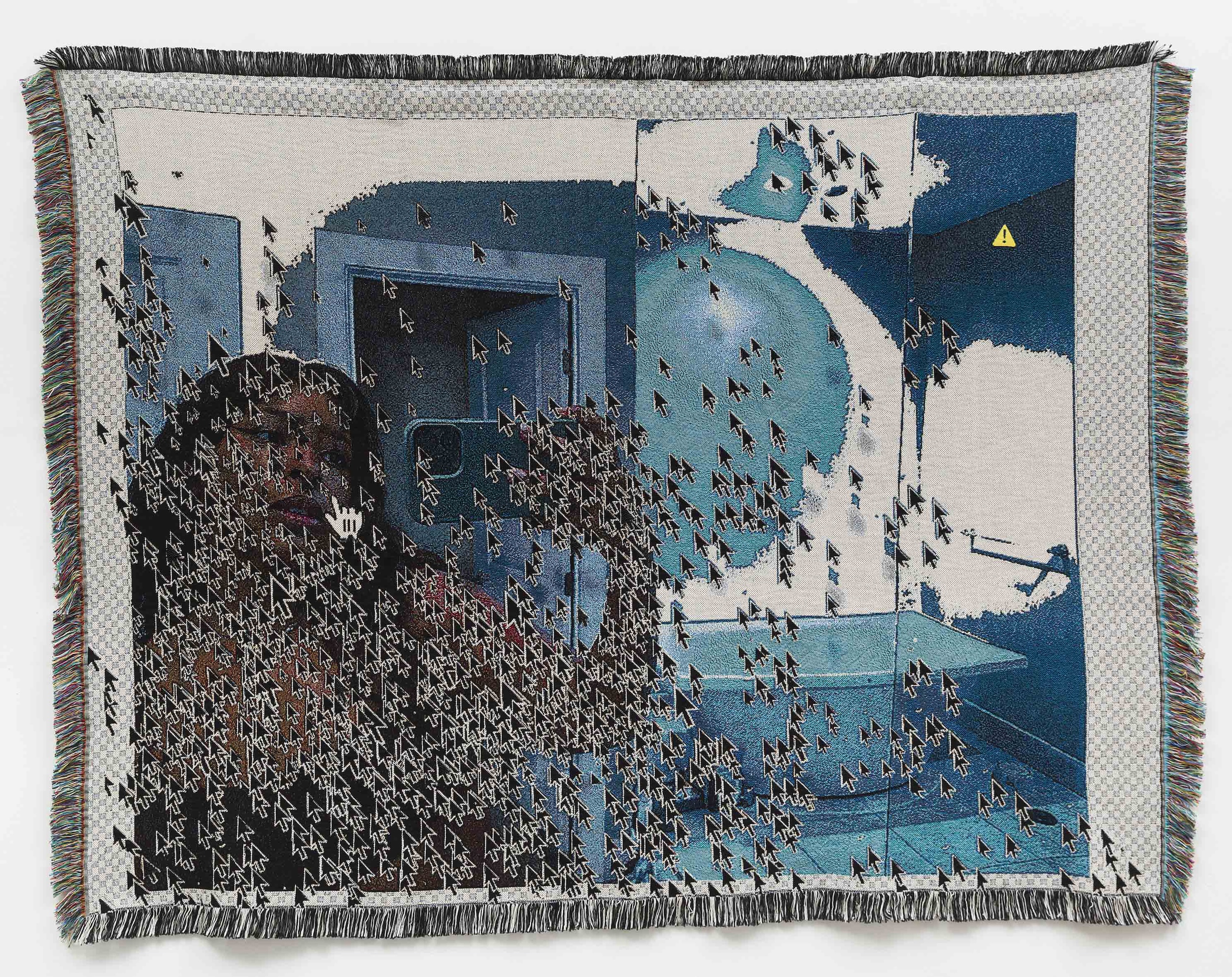

Often, as in Tirvengadum’s case, the stories being examined are directly linked to the artists’ own lives, existing at a nexus of personal and national histories. Three woven works by Arpita Akhanda combine portraits of her grandparents with reclaimed maps, reflecting on the couple’s displacement following the 1947 partition that created India and Pakistan. “In weaving – as a process, as a tool as a language – there are these two planes: the warp and the weft,” Akhanda explains, “For me, they are like the personal and the institutional, and when they meet together, what kind of narrative do they bring? The hide-and-seek that they play is a language that I use as a metaphor for the hidden narratives in these personal archives, suppressed by the larger institutional histories.”

This hide-and-seek dynamic is at play across the whole exhibition; ostensible historical truths are questioned and unexplored, often deeply personal, narratives are brought to light. Collage becomes a way to display realities that can’t or haven’t been rendered by the camera.

Vora says that she’s long understood collage as more than just a method of assembling and overlaying images: “I’ve always thought about it in the multiplicity and abundance it creates.” Such abundance unfolds dizzyingly across I Still Dream of Lost Vocabularies, an exhibition where images, events, places, people, personal histories and global narratives join to form a new kind of photographic archive; less traditional than most, perhaps, but certainly no less truthful.