Felicity Hammond. All images © Alice Zoo

Working in industrial spaces for 10 years, and fascinated by the contemporary experience of images, Felicity Hammond makes installations combining imagery and sculpture

In 2021, generative AI platforms such as DALL-E and Midjourney suddenly became available to the public, and conversations, debates and hand-wringing about the status of AI imagery in the context of art and photography started up. “Suddenly there was a crisis in photography, yet again,” says Felicity Hammond, an artist whose work has long concerned the relationship between the image – especially those generated by computers – and the material world. For her, this shift in discourse has been creatively potent. “It felt like my attention shifted naturally,” she says. “And became quite obsessive.”

Hammond came of age as an artist at a time when the understanding of photography was beginning to broaden and change. She graduated from the Photography MA at the Royal College of Art in 2014, where she was tutored by Lucy Soutter, Rut Blees Luxemburg and Peter Kennard, and studied alongside peers such as Alix Marie, Peter Watkins, and Dominic Hawgood; before that she pursued an undergraduate degree in fine art, with an emphasis on photography, under Richard Billingham at Cheltenham School of Art. “I was always encouraged to work with the camera in expanded ways,” she says. “I came into it not really as a photographer at all, but through an intense love of making.”

At the RCA, from a starting point in collage, she began to bring together printing, material and sculpture, “making these installations that felt somewhere between image and object”. She was fascinated by architectural renderings, the mocked-up digital versions of places and spaces to come, seen on hoardings along building sites for identikit architecture, from London to Dubai to Shanghai. “I started to think about the pixellation and the warped quality when these things are blown up,” Hammond says of these images. “And so, does the materiality carry the ruin of the digital? A lot of it was around ruin, both within urban and digital space. That’s why the materials were important, because I wanted to enact the digital physically.”

“I’m not interested in making luxury fine art objects – I’m interested in the industrial, and manufacturing, and the actual techniques rather than mimicking them”

Hammond works closely with photography – she was awarded the Single Image Award in British Journal of Photography’s 2016 International Photography Award – but from some of her earliest efforts as an artist, was thinking into three dimensions. “It became as much about architecture, and politics of urban space, and gentrification, and ruin as it was about photography, and the screen, and the lens,” she explains. “What happens when you turn the lens of your camera back on the computer-generated image and make it photographic, and then materialise it? It’s all about these feedback loops and cycles between image and material and sight and screen.”

Hammond has always worked in and from studio spaces: straight after art school she moved to a live-work warehouse in Tottenham with some of her coursemates, which she describes as “chaotic and fun”. “I was very nomadic,” she adds, detailing moves over the course of a few years from Tottenham to Hoxton to Hackney Wick and through various residencies, often living on top of or alongside her work. Her airy current studio, in Sydenham, south-east London, has had many different lives. “That office used to be my daughter’s bedroom,” she says, gesturing towards a room full of monitors, where her partner now works. Before it was a bedroom, Hammond used it as a recording space during her time playing in bands. She and her partner still often collaborate with artists in the building’s other studios, and the whole community has put on nights in the project space on the ground floor.

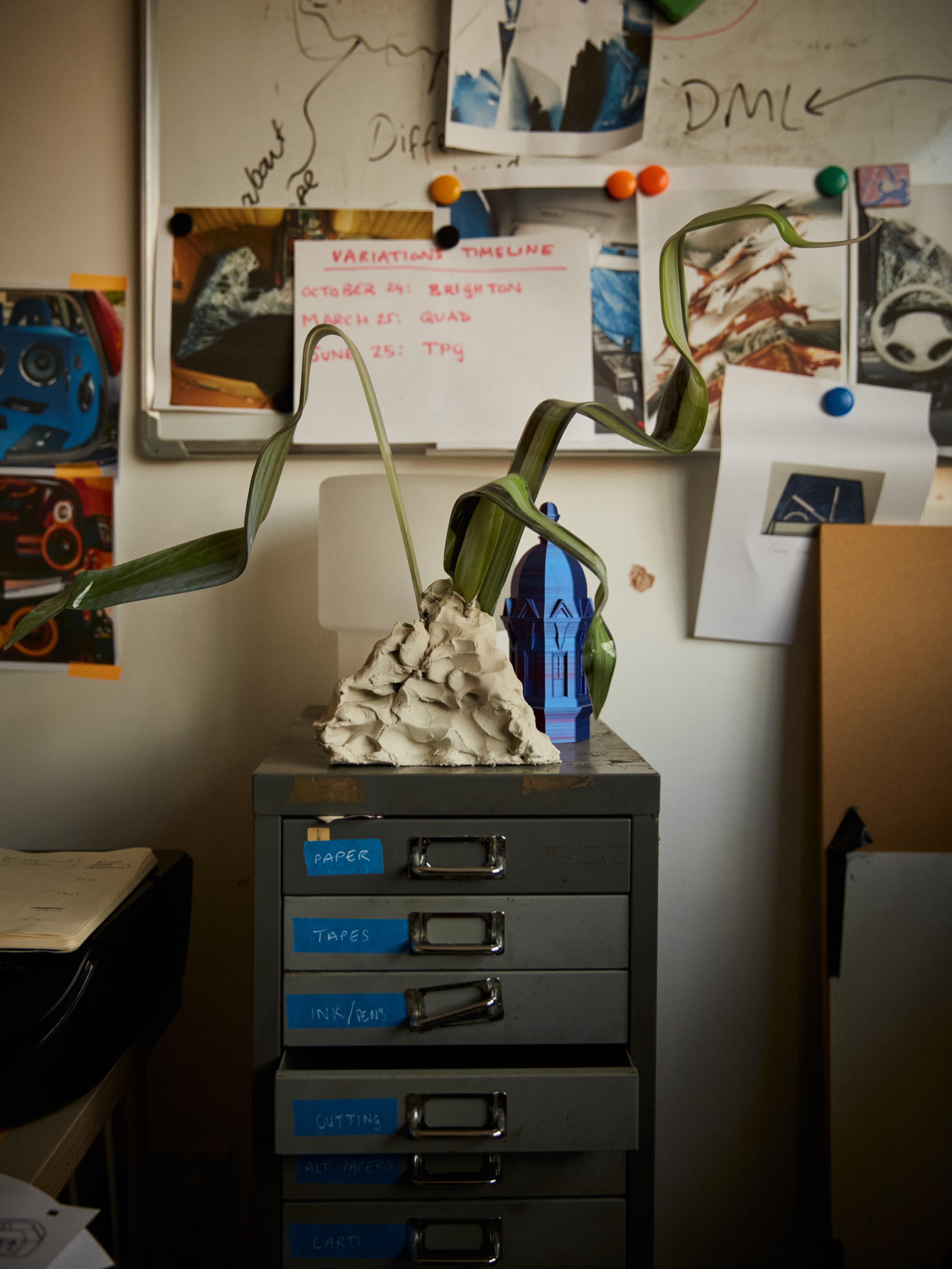

On the day I visit the sun is shining, casting light through the leaves of plants on both sides of the space, the sky blue from the top floor. Hammond and her family eventually moved out of the studio in 2022, after the intensity of living and working in the same few rooms during the pandemic, and when she started to receive more commissions. Suddenly, living on top of her work was no longer feasible. Today, the studio is full of works in progress: a huge print, almost the length of the room, laid across a table; the flattened side panel of a car, a high- gloss navy blue, mounted; and the bulk of a new piece, Rigged, from her recent project, bolted to a tall, orange frame.

This latest work, Variations, is the result of the Ampersand/Photoworks Fellowship, a £15,000 award that gives mid-career artists the opportunity to develop an original project. Hammond applied after the culmination of her 2021 solo show, Remains in Development, which toured from C/O Berlin to Kunsthal Extra City in Antwerp. “I formulated a new research question around data-mining and geological mining,” she says of the application. “To me, it felt like there were these two worlds, and there was potential to interrogate them through collage – collage being this perfect place for investigating potentially disparate things that have a relationship.”

Alongside these collages, she began to generate AI images as tests to understand the technology, and became curious about the way she was presented with four options: versions one, two, three and four of a given prompt. She wondered how that system might be applied to a curatorial framework. “I knew I wanted to somehow materially enact the processes that generative AI uses and draw our attention to it through a different lens,” she explains. “I was interested in the fact that there are global logistics, and global territory, of this particular technology. It’s not isolated to our screens, and in order to create the hardware to use it, we need minerals from one place, they need to be shipped from here to there, we need data centres elsewhere. There is this expansive territory.”

With this premise as a starting point, the first variation, Content Aware, took the form of a shipping container, exhibited in Brighton last October during the Photoworks Weekender; the second, Rigged – the one which currently stands in progress in her studio – will go to QUAD in Derby in spring. For the third variation, Model Collapse, which will show at The Photographers’ Gallery in London not long after that, Hammond will use images and data gathered from security cameras fitted to the first and second variations, the installations imaging the viewers and, thanks to a reflective wall opposite, themselves.

“The idea is that there are some people trying to hack the machine and to infect it with its own images,” Hammond says of the third iteration. “But what happens when AI-generated images that aren’t real, physical things in the material world are fed back into it? How does it interpret that data, and how do they start to shift and almost poison the machine?”

The exact form of Content Aware is yet to be determined, as it will depend on this gathered data; Hammond will have to work fast to interpret it and re-imagine the next variation in real time, as there are only a couple of weeks between the installation in Derby and the next in London. “I’m less interested in actually what it does to the system and more interested in that as a framework, or concept,” she says. “So that’s why I’m re-enacting the images; and I still don’t know what that’s going to look like.”

The final work, Repository, considers the idea of the archive, where all of these generated images are housed, where the data is stored, and what happens when these endless machines are discarded and go back into the ground. Crucially, none of the Variations have been conceived as documentary or realistic, instead they reflect on aspects of the AI machine as a place for speculative engagement. “None of these are descriptive about the process, it’s more a sort of theatre,” Hammond explains, “or a sort of collapsing and bringing together, creating stagings and sets for us to imagine.”

Given the questions, and even critiques, Variations implicitly raises in its exploration of mining (digital, material) and decay (digital, material), I was surprised that Hammond is using generative AI as part of her process. “I’m actually battling with that as we speak,” she tells me. She remembers receiving the first couple of days’ worth of data from the camera attached to Content Aware in Brighton, and preparing to use AI tools to work with it. “As I started doing it I was like, ‘What am I doing? I don’t want to be doing this’.” She began to wonder about the possibility of using it as a training set for herself instead, as though she was the generative AI system that her work is staging. “I don’t need this,” she recalls thinking. “I’m enacting it.”

“I feel like I have to engage with it, but I don’t feel like I want to use it as an integral part of the machine of art production,” she says of her current take on AI-generated imagery. “Maybe it’s similar to travel – I fly, but if I don’t have to fly I’ll get the train. I feel like maybe it’s the same for AI. I need to use it for this part of the process in order to be able to interrogate it further, but I’m not going to sit and make thousands – or tens of thousands – of images, just training training training, data data data. Firstly it’s not useful for me, but I feel uncomfortable doing so.”

Aside from environmental concerns about the technology, Hammond takes a pragmatic view on the impact of AI-generated images. “I don’t really think it’s too different from CGI,” she says. “It’s just an extension of non- lens-based ways of making photographic works – and by photographic, I mean in the broadest sense of their relationship to the real, and all of those dialogues that have taken place throughout photographic history.

“Whenever we’re using a medium, we need to be reflecting on what that medium is, and how it relates to the subject matter that we’re working within,” she continues. With AI, as with any other technology, the medium must be at least part of the message. “I’m really sure that I don’t want to use it on this surface level. The context and medium are so interlinked, so I feel like the idea of making work that uses a camera that doesn’t somehow reflect on or interrogate the photographic… Well, somehow I feel like that has to be a part of the field that is being investigated. The same absolutely goes for AI-generated images. If you’re using it, it has to reflect on the technology. It shouldn’t just be a means to an end.”

And so it follows that her works meticulously make tangible the processes they examine – the process by which, for example, the digital degrades and is eroded just as the physical is, which is hard to feel as truth even as it is understood intellectually. Works such as Variations stage and concretise the ruin of the digital and, as a result, the viewer can experience that truth as embodied, physical. “I’m asking how the ideas of the work interact with the material world,” Hammond explains.

Her working process is an extension of this commitment to the tangible: the objects, installations and sculptures she makes, whether she makes them herself, or works with others to bring them to life, are conceived and designed with these principles in mind. “I work a lot with non-photographic spaces, places that work with industry as opposed to the arts,” she says. “When I get something spray-painted I go to somewhere that spray-paints machines, as opposed to a fine art fabricator. I’m not interested in making luxury fine art objects – I’m interested in the industrial, and manufacturing, and the actual techniques rather than mimicking them.

“That’s perhaps why the work is never slick,” she continues. “It has these elements that might be very slick, but there is still a sort of roughness – you can see the bolts. I want it to somehow be true to the material that I’m responding to and the context I’m responding to, rather than a sort of fetishisation of it.” This materiality and attention to the industrial is personal for Hammond, informed by her early life – she grew up in Birmingham, where her father worked in a factory. But it is also a response to her lived environment.

“I’ve lived in industrial spaces for the last 10 years of my life, so I’m strongly informed by the materials that I’m around a lot,” she says, looking over at Rigged. “So, thinking about things like the bolts, they just feel like part of my material world.”