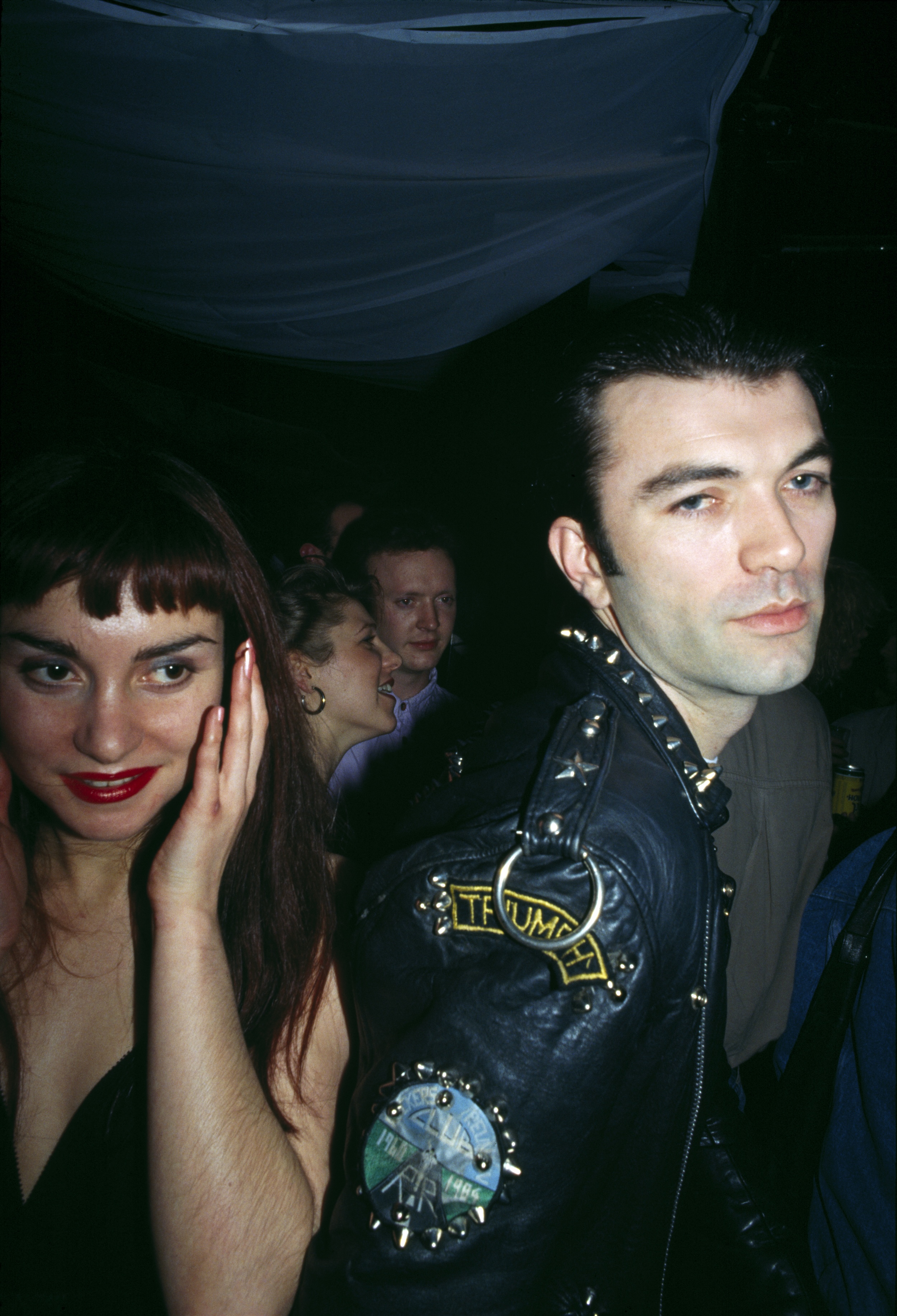

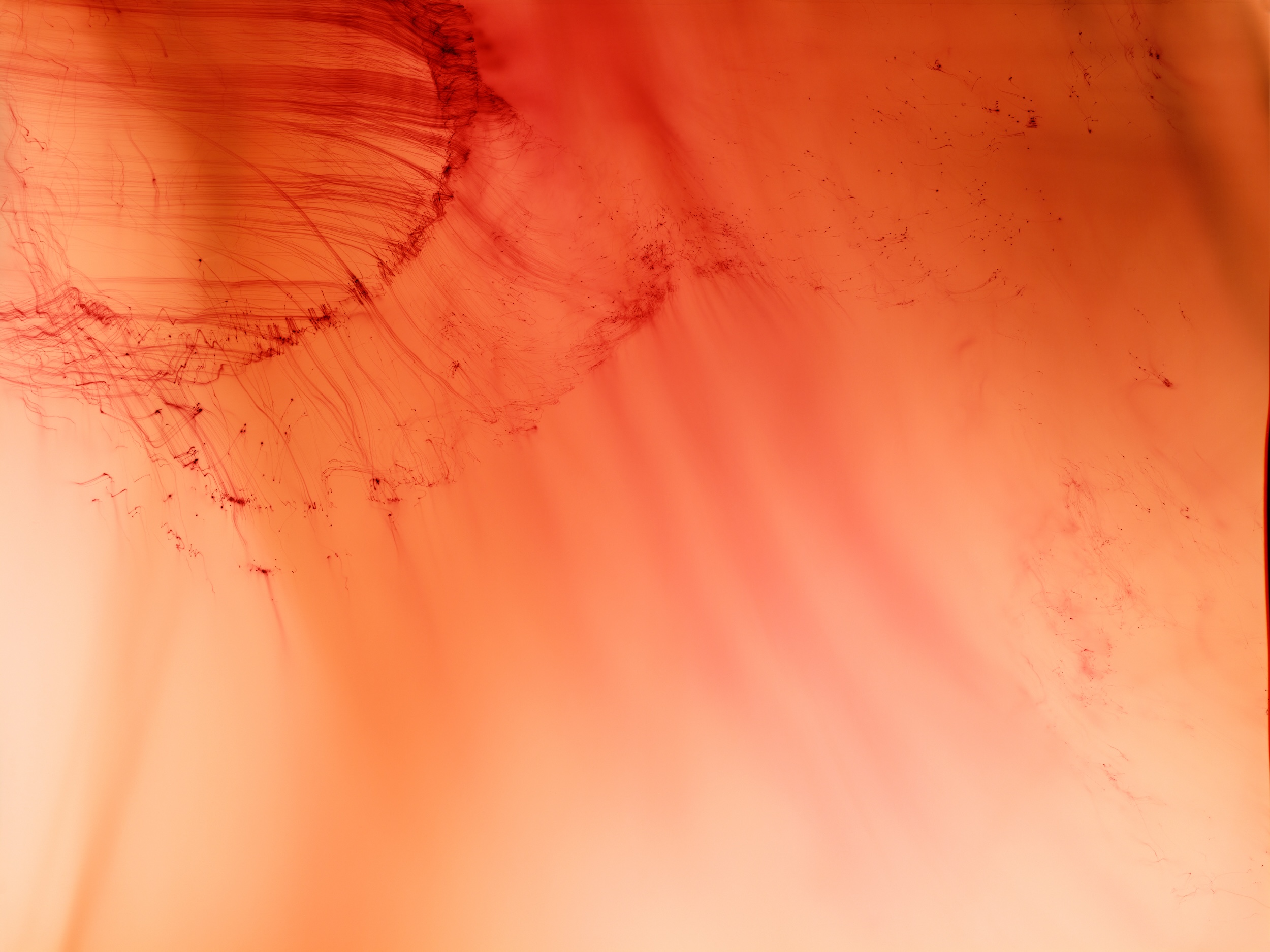

The Cock (kiss), 2002. All images © Wolfgang Tillmans

With a huge exhibition in the Pompidou Centre’s vacated Public Information Library, the artist also asks how we might consider the present to see into the future

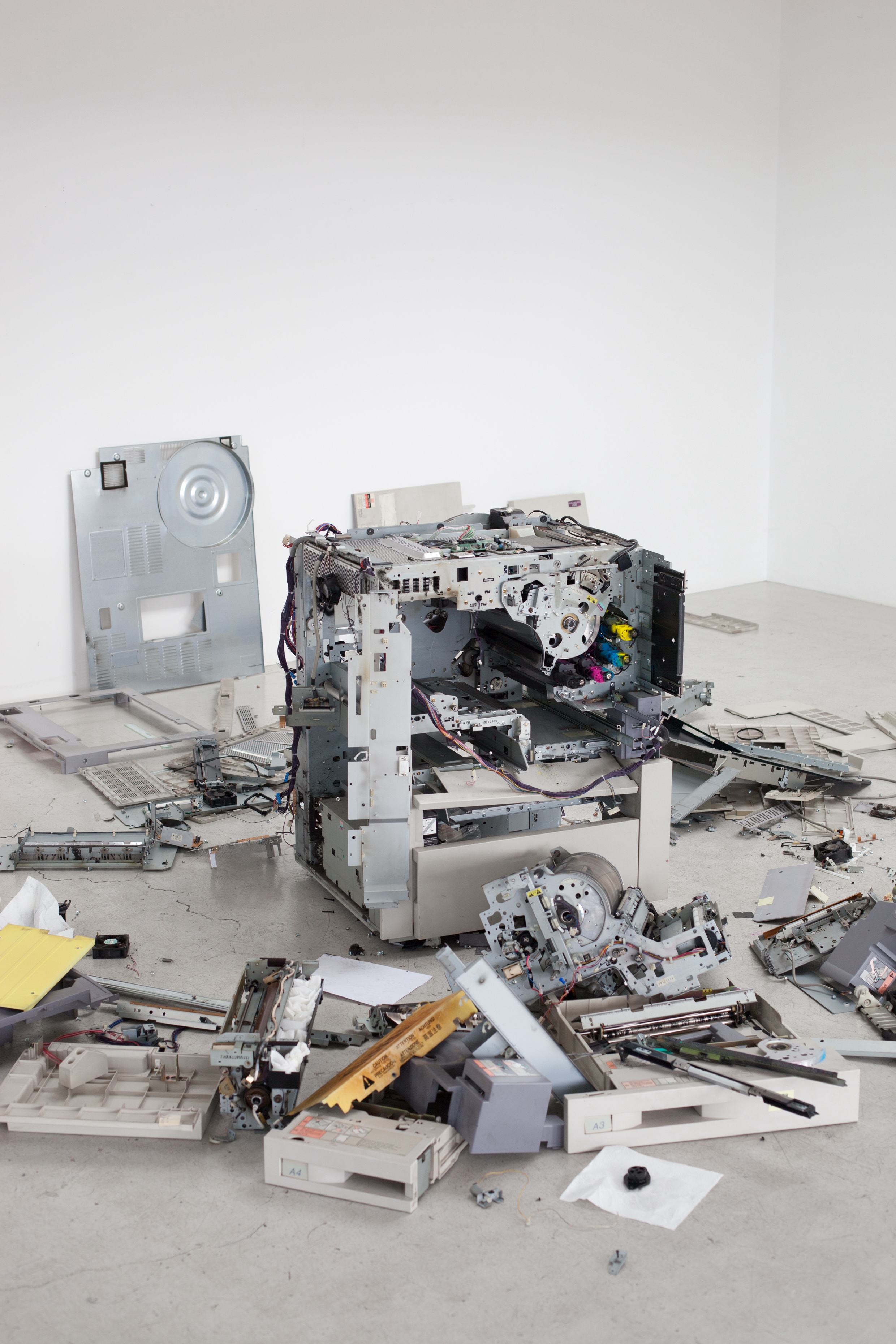

I’m speaking with Wolfgang Tillmans in the evening on 23 December; he’s at his parents’ house, having gone back to spend Christmas with them. I ask if it’s okay to record our conversation, and he says he’s recording it too, “for my archive and security, to have a double, and I don’t know, it’s just useful”. Both factors testify to his commitment to his work, which also saw him stage his first exhibitions as a teen in Hamburg, then move to the UK in 1990 to study photography. His first shows included an early outing at Café Gnosa, Hamburg in 1988, titled Approaches and including images photocopied up to 400 per cent of their original size; suggesting his singular vision, it also has a contemporary echo. Tillmans is kicking off 2025 with an exhibition at Maureen Paley, London, where together with Air de Paris, they are showing his photograph of a carefully-dismantled photocopier alongside Pati Hill’s xerox experiments.

And 2025 will keep going from there, with Tillmans opening a solo exhibition across 33 rooms at Haus Cleff in Remscheid, his hometown, on 12 April, followed by a two-person exhibition with Boris Mikhailov at Yermilov Center, Kharkiv on 25 April. Prior to these, he opens a solo show at the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden on 08 March titled Weltraum [‘Space’], his first major museum exhibition in Germany in over half a decade. Weltraum focuses entirely on work made since 2022, starting from a trip to San Francisco in which he explored technology companies. Following this journey through Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mongolia, Tillmans investigated internet and AI companies and their physical traces, alongside staging shows such as To look without fear at MoMA, The Art Gallery of Ontario, and SFMoMA, and Fold Me at David Zwirner, New York. It’s a particularly impressive feat given his approach to exhibition, which is that installation is an integral part of it, and always site-specific. He painstakingly installs each show himself, with his own team, and takes a cutting-edge approach to display, including magazine tearsheets, pinning unframed prints to the walls, utilising horizontal surfaces, and also including mirrors.

His ongoing Truth Study Center, which he started in London and exhibited with Maureen Paley in 2005, combines newspaper cuttings, photographs, photocopies, drawings and objects, for example, laid out on trestle tables like so many specimens to observe. His exhibition at MoMA included a mirror work by Isa Genzken, meanwhile, reflecting a huge print of his image wake, 2001, into infinity. “In a career spanning almost four decades, he has consistently redefined the medium of photography through a seamless integration of genres, subjects, techniques, and exhibition strategies,” states David Zwirner gallery, which has represented him since 2014. “Tillmans seeks to expand the poetic possibilities of the medium while addressing the fundamental question of what it means to create pictures in an increasingly image-saturated world.”

“It wasn’t that I first used photography and then decided to become an artist, it was the last medium that I found, and I realised I can speak with the photographic medium about what it feels like to be alive today”

Tillmans’ biggest show of 2025 is at the Centre Pompidou though, both in terms of prestige and literal space; the Pompidou is closing for five years for renovation, and he has been invited to take over the vacated Public Information Library [Bibliothèque publique d’information or BPI], an entire floor measuring some 6000 square metres. The exhibition is titled Rien ne nous y préparait − Tout nous y préparait [“Nothing could have prepared us − Everything could have prepared us”], and Tillmans won the opportunity partly because of his site-specific approach. “Laurent Le Bon and Xavier Rey [president of the Centre Pompidou, and president of the Musée National d’Art Moderne, housed in the Pompidou] were interested in doing something that has a perspective of the future included in it,” he explains. “They were interested in the original architectural vision of the Pompidou as an open base, primarily without walls.

“Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano [architects of the Pompidou] envisioned and designed the floors without any pillars, columns or walls – you have these characteristic beams in a zigzag structure, which give it this fantastic look and also create an open plan of 45 meter widths and 100m lengths. But after the building opened, people started to not hang all the works from the ceiling, then build walls. It really has become an accumulation of architectural interventions – except always, since day one, they had one floor that remained open-plan, which is the second floor, the Bibliothèque publique d’information. Lauren was interested in giving the open plan floor to one artist to somehow attempt an exhibition design to do with the future, connecting the past and future. I, of course, saw it as a huge opportunity, and also a huge challenge. It is not exactly designed as a clean art gallery.”

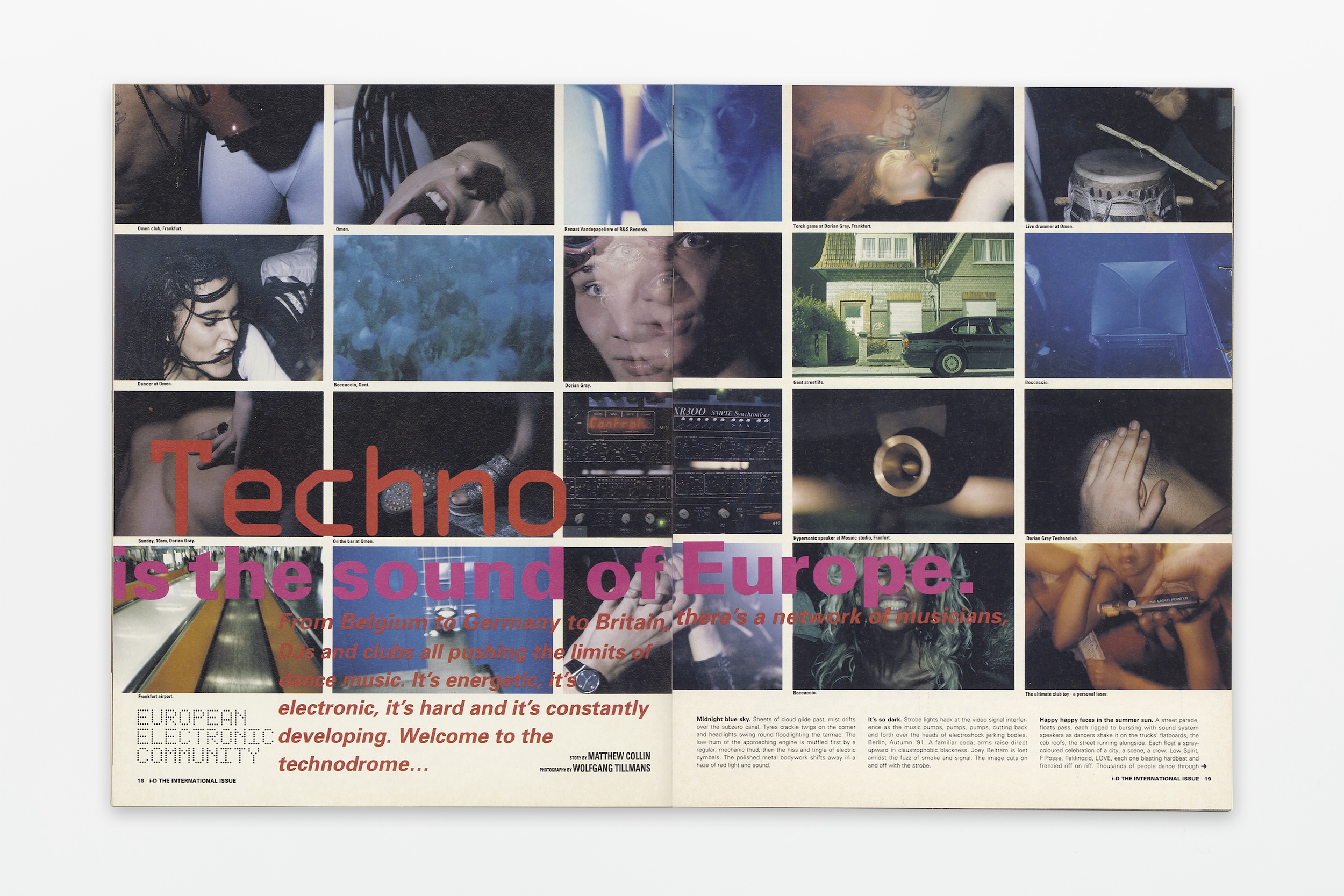

The BPI also has an unusual ethos; designed to democratise access to information in the pre-internet 1970s, it emphasises the current and the up-to-date. It doesn’t store ancient, precious manuscripts or books (they go to the Bibliothèque nationale de France), and includes an incredibly wide range of publications and journals. It also clears out its holdings every year, jettisoning some 10 per cent of its older material to make room for the new, a factor that fascinates Tillmans. He has taken exactly the opposite approach with his work, archiving negatives, files, prints, books, magazines, interview recordings, display cases, and more. At the recent group show in Tate Britain, The 80s: Photographing Britain, Tillmans included spreads from i-D from the early 1990s, for example, taped to the walls.

At the Pompidou he will “show books in their entirety”, meanwhile, bringing 66 copies of his book Concorde so he can display all 128 spreads plus the front and back cover; he retained the copies for just this purpose when the book’s fifth edition was published in 2017, but has never been able to do so before because it requires such expansive space. He’s also doing the same with his 2012 book FESPA Digital / FRUIT LOGISTICA, which shows produce arrangements at an annual trade convention in Berlin alongside images from one of the largest trade fairs for digital printing, and he’s making other huge tables for an in-depth look at astronomy – including the original tables on which he first showed Truth Study Center at Maureen Paley, 20 years ago. “It’s an exciting opportunity to have that much horizontal space,” he says.

He will also include the latest evolution of Truth Study Center, his ongoing research into information, what we can understand from it and how we interface with it; as this brief introduction suggests, this theme runs through his practice, and “organising knowledge and archiving and record-keeping” was another major intersection with the BPI. For Tillmans this interest extends to the technology of photography, how images are made by the camera and when they are printed; his experiments in abstraction consider the composition of analogue photography, for example, while his interest in astronomy (which started when he was a child) suggests what we can know of space – and more widely what we can glean via science.

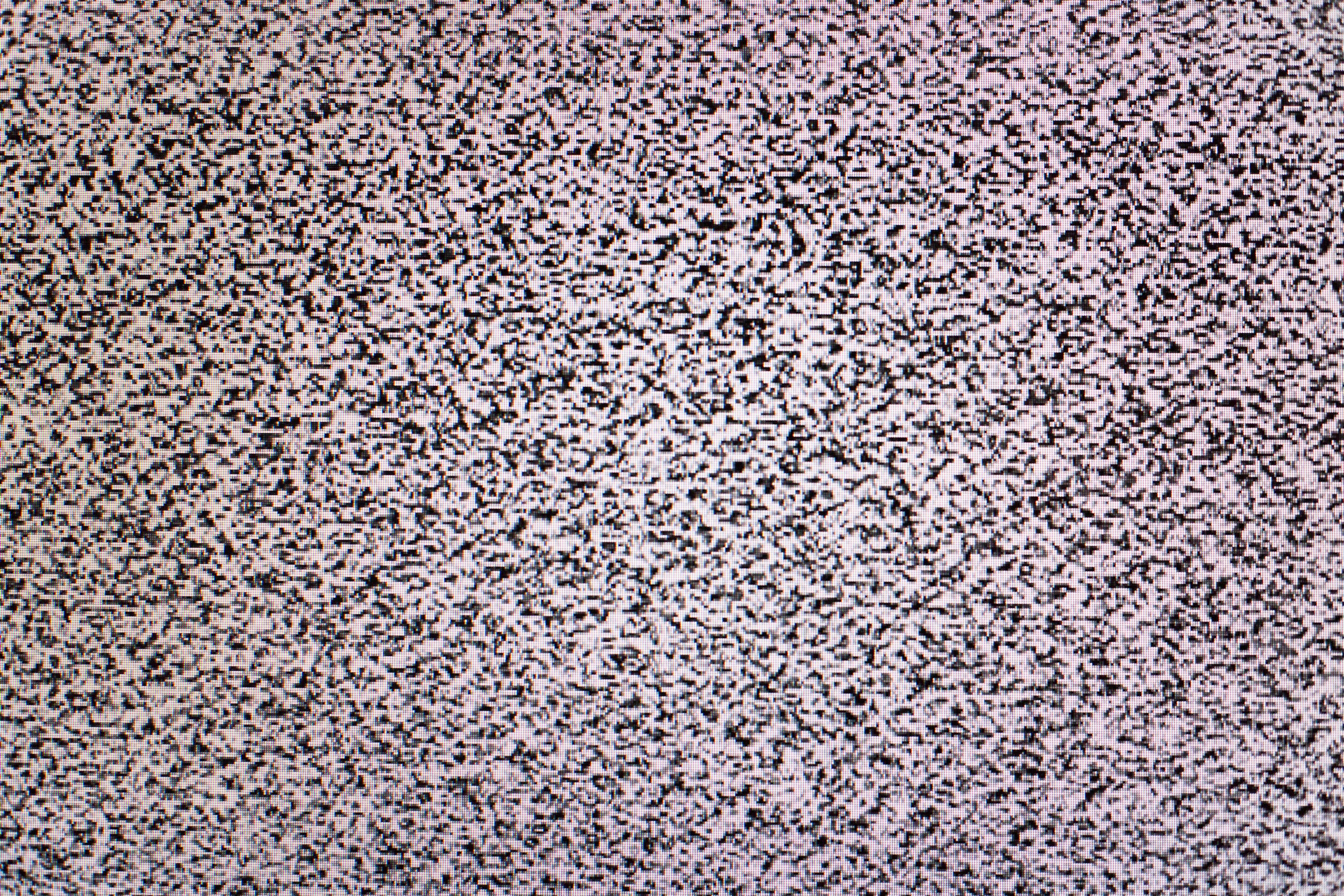

At the Pompidou, “since the exhibition crisscrosses around the role of media,” he will also show the largest-ever iteration of Sendeschluss / End of Broadcast, 2014, photographs of TV static that initially look black-and-white but “when you come closer, really close, you suddenly realise it’s all made of colours,” he adds. TV and the media suggest questions around the circulation of knowledge, and access to it, another mutual interest for Tillmans and the BPI. The BPI prides itself on being open, he points out; anyone can enter, there are no library cards, and readers do not have to register themselves. “It’s an insistence on the democratic access to information and knowledge, which came very much from the 1960s when they planned this library to be open without threshold,” he points out. He describes 2000 people sitting, peacefully working alongside each other, as “an incredible utopia”.

Tillmans has long been attracted to lived, collective utopias – dancefloors, for him, suggest a similarly idyllic community, and have recurred in his work – so he was keen to show the library in action. Rejecting simply filming those studying, as getting permission from each individual would be so hard, he instead organised a special opening one Tuesday (when the BPI is usually closed), on which they could work as usual on the proviso they could be documented. “Real pictures unfolded that I was able to film, primarily film, and this will be displayed on 60 screens, computer monitors, in the self-learning centre,” he says, referencing the BPI’s study cubicles. “It will be a living portrait of the library.”

The exhibition will include other screens too, with two storage spaces repurposed into projection rooms and, at the end of the exhibition, an LED screen. LED is a technology he has hitherto mostly resisted, because these screens have “such an overwhelming impact” and because they require so much power “when we all need to conserve energy”, but here he wants to use it to show images in daylight; it will be in a space overlooking the Stravinsky Fountain outside the Pompidou, designed by Jean Tinguely and Niki de Saint Phalle, so he felt it inappropriate to fence off a darkened projection room. Tillmans also contributed a work to the Pompidou’s giant LED screen in summer 2024, though, when Nike paid to arrange a grid of LED screens over 140 meters of the Pompidou’s glass facade, which was used to show Nike campaign materials and also artists’ videos. Tillmans, while wary of the power consumption and the advertising structure, “embraced the opportunity”, he says, contributing a playful video Leafy Green Architecture / Architecture de feuillage vert, 2024, which suggested the escalator tube snaking up the Pompidou as a caterpillar.

I comment that this was an interesting project, resurfacing the Pompidou – designed to be transparent in all senses, “to be open without threshold,” as Tillmans described the BPI – with a screen, and venture that the increasing prevalence of such technology is blurring our sense of what’s real and what’s not; I ask Tillmans if he is partly trying to get us to question images, in the face of their increasing ubiquity. “I like to say yes to what you say, but I also don’t want it to just be an easy yes, as if I know what questioning means,” he responds. “This questioning can’t just be a gesture of questioning, it really has to be open to whatever results come out. But this fascination for photographic image in all its many shapes and forms, has been at the core of me engaging with it, and that’s why, in the end, I settled on photography as the medium, as my art.”

“It wasn’t that I first used the medium and then decided to become an artist, it was the last one that I found, and I realised I can speak with the photographic medium about what it feels like to be alive today,” he continues. “That was in 1990 approximately, and 35 years later I’m still not tired of it – even though I couldn’t imagine, I couldn’t think, that over the course of those 35 years, when photography has become so central to almost every person’s life in a world within reach of electricity, that there’s room left for nuance. But I found that there still is room for nuance, to constantly also insist on it, and be open to finding it in new places, or to insist on preserving this thing.”

Still, he says, he’s not sure if photography will remain ascendent, given the growth of AI. “In my exhibitions, trusting that I haven’t moved pixels around, the promise that I give, that is what holds value,” he notes, adding that in the future, audiences will not be sure whether images are the result of light entering cameras, or creations. He points out all cameras distort, the lenses flattening the view, and that many of his still lifes are carefully composed – but even so, “an experience of a sensation at the moment” is something. In Tillmans’ case it’s held political import, his images of people suggesting embodied experiences in which we directly encounter the world, through all our senses, rather than receiving pre-packaged information. And images such as The Cock (kiss), 2002, or arms and legs, 2014, directly speak up for love, no matter who it is between.

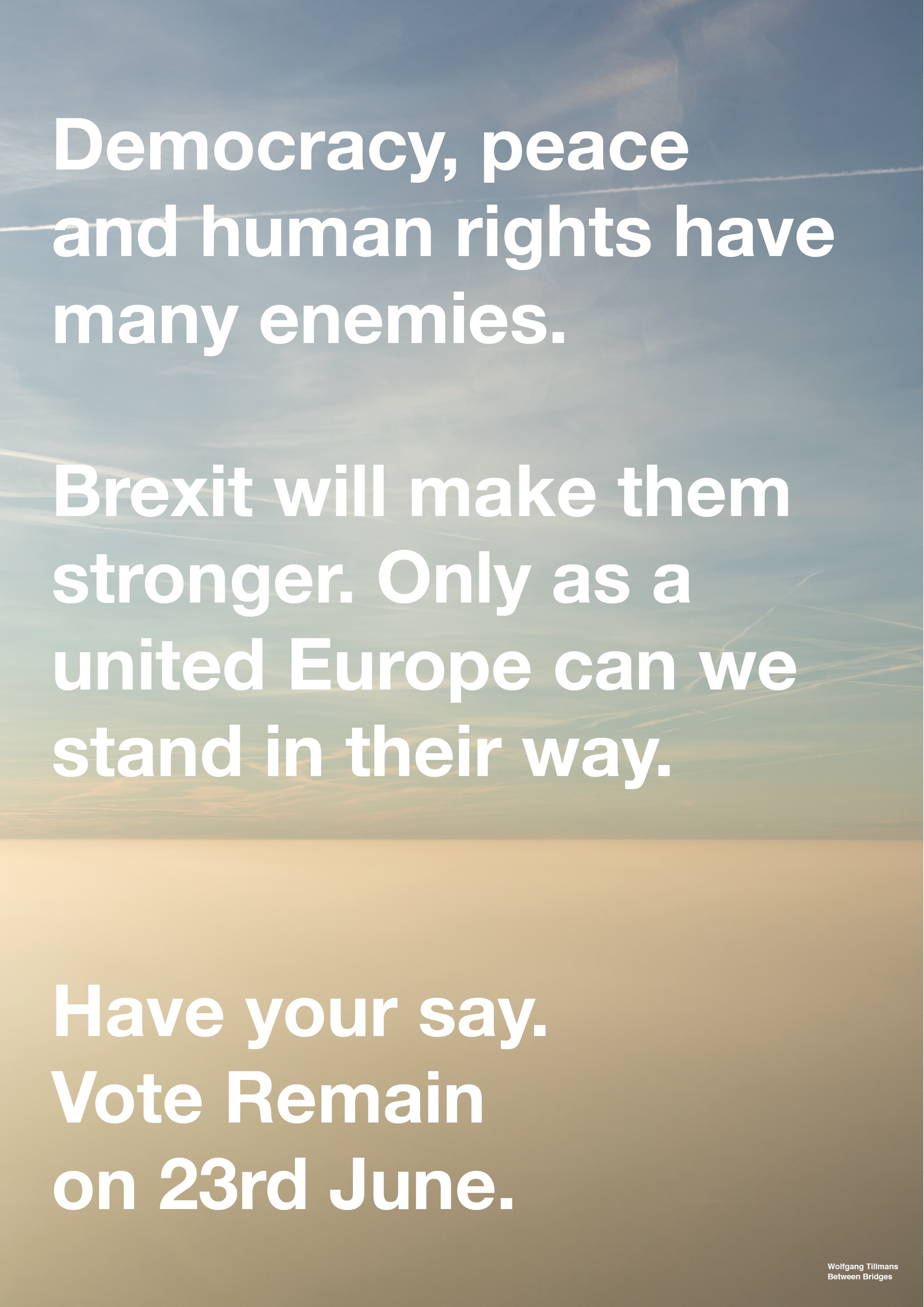

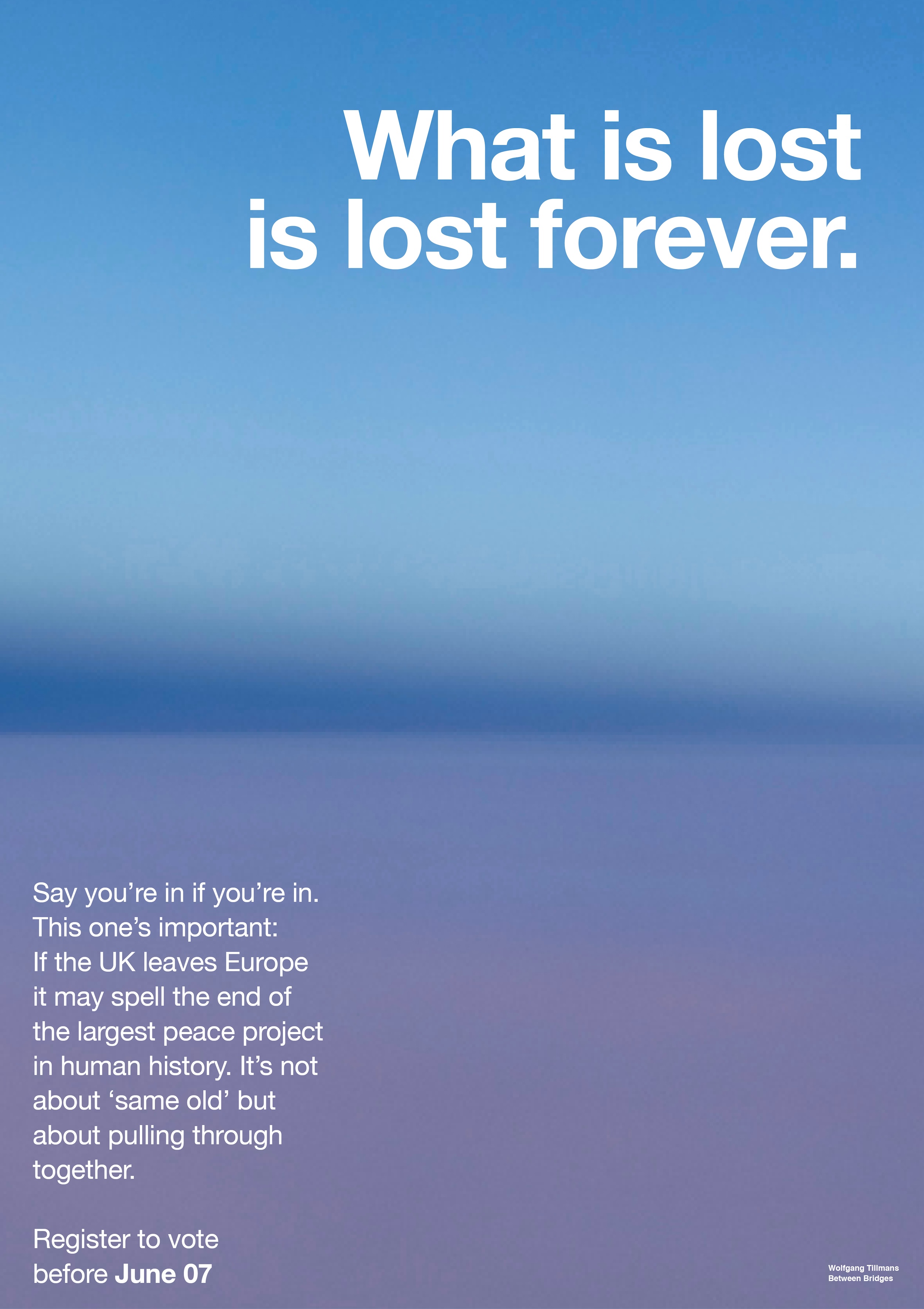

Tillmans is gay and says this means he has always considered himself political, and his work fully engaged with society, “because I observed in the 1990s that the freedoms I had to live my life to the fullest were fought for by generations before me. There’s always been a clear connection between the private and the public and the political [in my practice]”. But he adds that he never wanted to be a campaigning artist, and was keen to make work which as many people as possible could connect with. “Not being locked down as one demographic was very important to me,” he smiles. In the last eight years his output has become more directly political, however, Tillmans taking to Instagram to circulate text plus image combinations advocating for the UK to stay in the EU, or Americans to vote against Trump, or Georgians’ right to free elections (among other causes). These efforts were prompted by the UK’s Brexit referendum in 2016, he says, when he realised that the right wing was passionately promoting British nationalism, but no one was celebrating Europe.

“I realised that the outcome [of the vote] could go bad,” he says. “The peaceful Europe that I experienced since I first came to London… that reality was under attack, and that’s where I suddenly found the language and image combination to make these posters. And then I realised this is an ongoing phenomenon across the western world, rebounding nationalism, and I started to use my Instagram channel just as much as mail or printed matter. The way I used social media…. had its predecessor in seeing magazines as magnifiers of ideas that I wanted to get behind and support. Working for i-D magazine [in the early 1990s] was driven by content, not a move to build up a portfolio or get advertising jobs but a journalistic interest and awareness of the power of the travelling printed page.”

Tillmans points out he doesn’t know who will be in power in France when his show opens; elections could take place in June 2025, because the current government is an uneasy alliance – formed via votes against the Far Right – and it’s possible Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National could win. It’s a potential future which is shocking but has also been a long time coming, as Tillmans’ exhibition title suggests, Nothing could have prepared us − Everything could have prepared us. But that insight perhaps also affirms photography, a technology that can speak of “what it feels like to be alive today”, and thereby provides the opportunity to really observe the present – and therefore, perhaps, make cautious predictions. “I have always believed that roots for the now are of course in the past, with a true observation that one can get glimpses at how things happened, how things developed, how did we get there,” says Tillmans. “A lot of science is about careful observation of the past, in order to get clues about how we got where we are.”

His exhibition will include traces of the past in his images; it will also preserve history in his use of archive materials, such as old publications and display cases, as well as in architectural elements of the BPI itself. Tillmans wants to retain and repurpose, to make “quiet interventions” such as reusing old bookshelves and study cubicles rather than radically restyling the space; he’s also keeping the old carpet from the library, mostly grey but revealing footprints of old bookcases and tables via an older red carpet which lies beneath. The layout of the vacated BPI will be revealed like ghostly remains by the flooring, he says, “a bit like a negative”.

But he adds that he doesn’t want the show to be nostalgic, and that looking at the past can also suggest a positive vision on the future – particularly given what he describes as “this particular French desire for cutting-edge modern design, which ages in a quite dated way, but is also very sympathetic”. He is nodding to this retro-futurism by including images shot on the TGV train in 2011, for example, as well as Concorde, and says that the Pompidou’s ground-breaking architecture has also “completely survived, both dated and as amazing as it was on Day One”. All three examples draw on optimism for the future, as well as on bringing people together, or simply doing or looking at things differently, and Tillmans is keen to retain that sense of radical possibility. He even plans to physically embody it, in fact, making interventions in the vacant BPI such as installing an elevated platform, and positioning two huge mirrors to reflect the famous ceiling pipes. In both cases he hopes to help people see differently, both literally and figuratively.

“I find the most rewarding things [are] the playful, pleasurable things one can do with one’s eyes, and I have, from my astronomical youth days, learned about the importance of parallax, which is observation of one object from two positions nearby,” Tillmans explains. “For example, your eye is positioned nearby, and when you hold in front of yourself with outreached thumb, close one eye or the other, and you see how the position of the thumb changes against the backdrop. That is used in astronomy and science, and in navigation of course, parallax is fundamental. So the changing of one’s position and perspective is something that I find particularly interesting, but I’m speaking here also, of course, about the potential of changing perspective on political issues that you held, that seemed insurmountable or unchangeable or undiscussable. I’m speaking about the incredible, revolutionary change of perspective that Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers made for architecture with this building, and so I wanted to also create two moments of changed perspective.”

Wolfgang Tillmans’ Rien ne nous y préparait – Tout nous y préparait is at Centre Pompidou, Paris, from 13 June to 22 September 2025