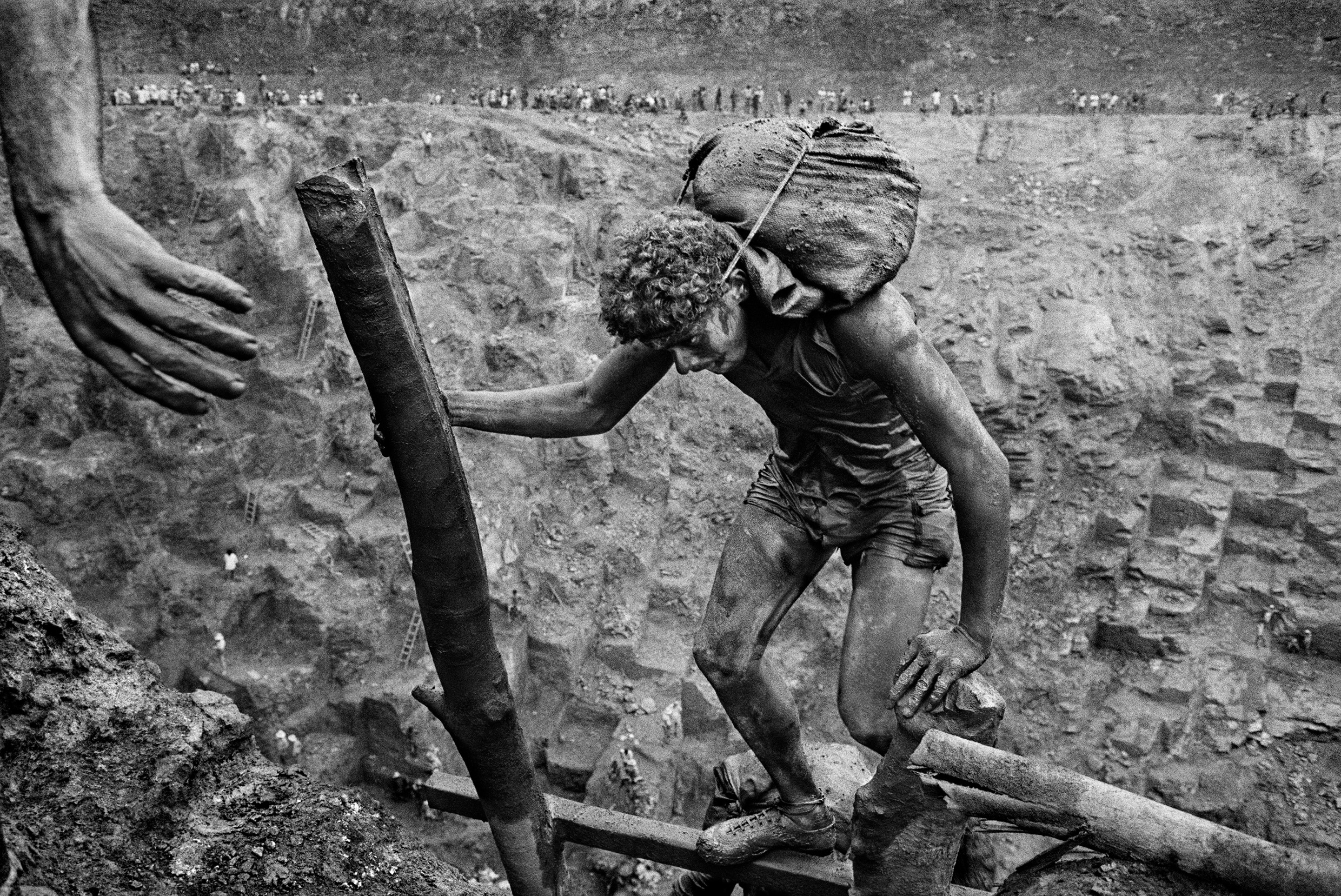

Serra Pelada, State of Para, Brazil, 1986. From the series Serra Pelada © Sebastião Salgado

Celebrated photographer Sebastião Salgado has died after more than 50 years of committed documentary work; here BJP draws on past interviews to give an insight into his approach

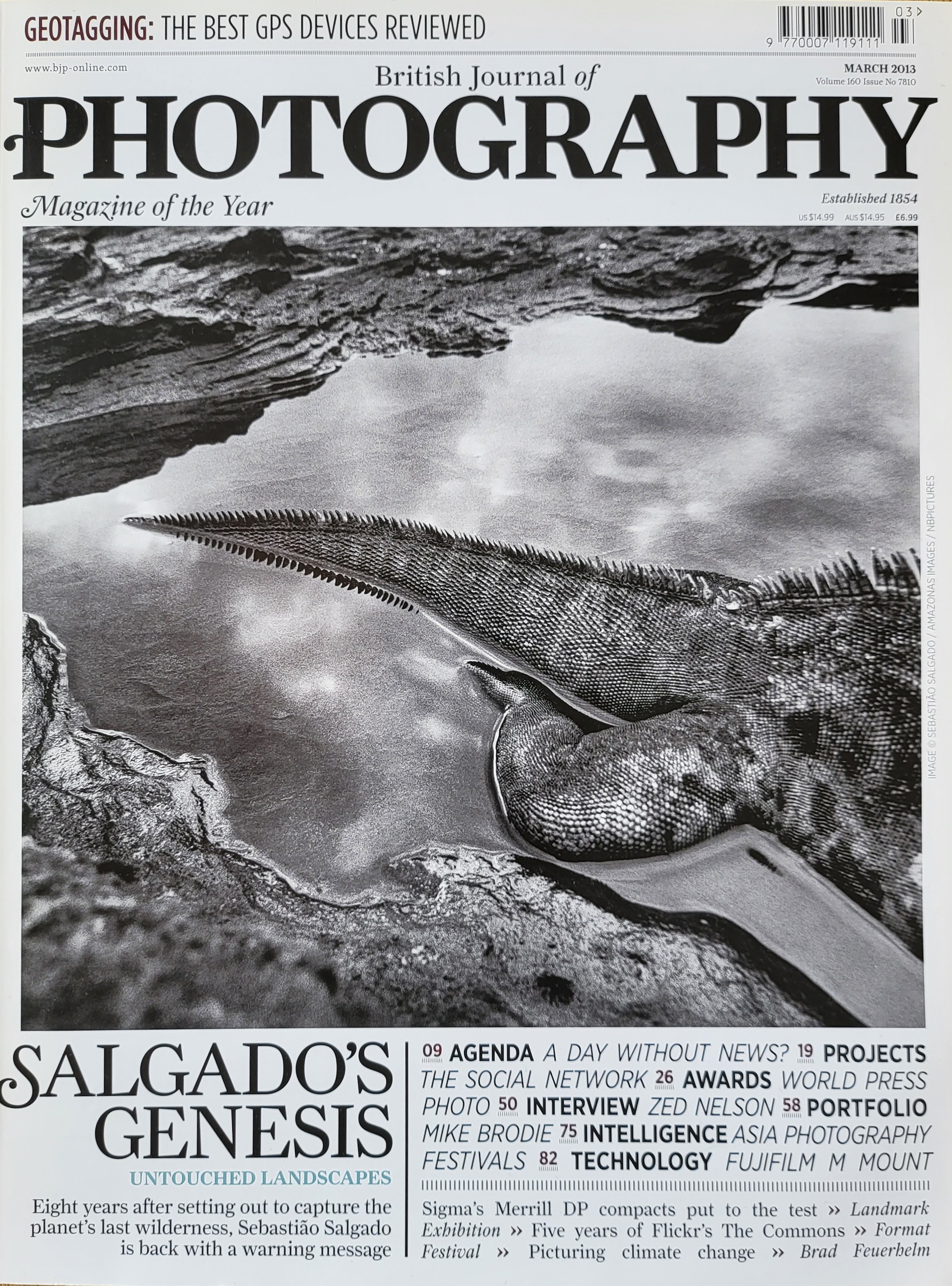

BJP was saddened to hear of the passing of celebrated documentary photographer Sebastião Salgado on 23 May 2025. Born in Aimorés, Minas Gerais, Brazil on 08 February 1944, Salgado studied economics before taking up photography, working on long-term projects published as books such as Sahel (1980), Workers (1993), Migrations (2000), Genesis (2013), and Amazônia (2021).

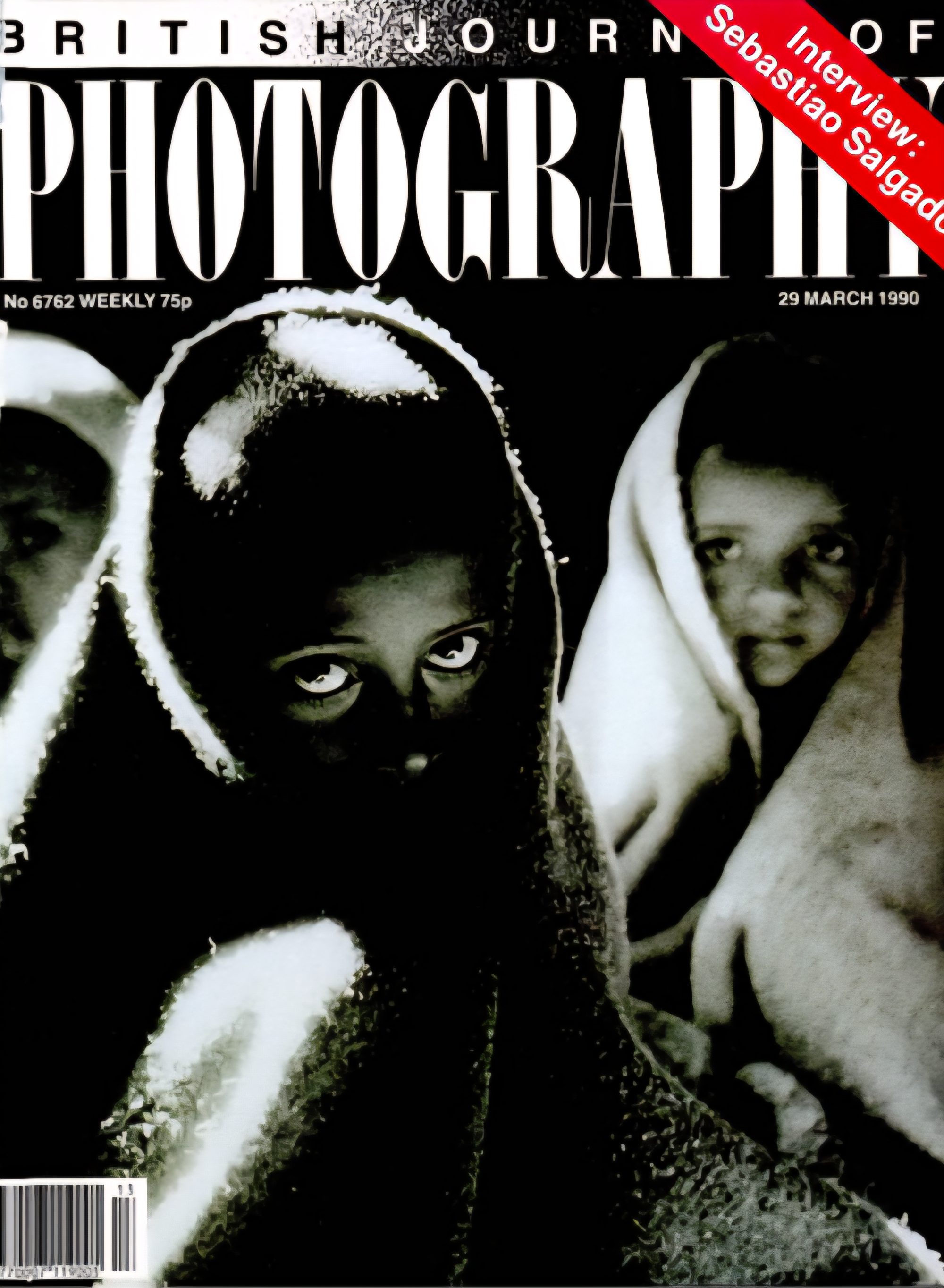

BJP covered Salgado’s work many times, and also interviewed him; Amanda Hopkinson spoke with Salgado in 1990 when his eponymous solo show opened at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, for example, while Peter Hamilton interviewed him in 2013, when Genesis was published. Salgado emerges as a photographer of conscience, dedicated to using images to highlight humanitarian and environmental issues. “What I most want my pictures to do is to lead to reflection and then action,” he tells Hopkinson. “The revolution only comes through evolution.”

Salgado got into photography in 1971 while working in London for the International Coffee Organization, after his wife, architect and later business partner and editor Lélia Wanick Salgado, bought a camera. “Four days later I had an obsession; a fortnight later, a camera of my own,” Salgado tells Hopkinson. “Within a month I had a darkroom.” Salgado initially worked on news reports then moved into documentary, working with photo agencies Sygma and Gamma before joining Magnum Photos in 1979. When Hopkinson spoke with him, his work was featuring in a Magnum group show at Hayward Gallery, as well as in his TPG solo exhibition.

“What I most want my pictures to do is to lead to reflection and then action. The revolution only comes through evolution.”

– Sebastião Salgado

Salgado and Hopkinson discuss images with which his name is now synonymous, including his shots of miners toiling in the Serra Pelada gold mine, which were made between 1986 – 1989, and some of which were published by The Sunday Times in 1987 [BJP’s article by Neil Burgess gives an insight getting it into print]. “I’m a reporter. I only take pictures of people. The important thing is to concentrate on the essential, by which I mean the dignity of humanity,” Salgado tells Hopkinson.

He’s also adamant he doesn’t want to convey vague impressions of generic suffering and – keenly aware of his position as a Brazilian, born outside the West – is alive to the power hierarchies that create inequalities such as the mines. “I admit there’s a very specific message in my work,” he tells Hopkinson. “The Third World has never been as poor as it is today. The cost of raw materials is dropping while that of industrial products continually rises. The developing countries have never been as poor or as dependent as they are today.”

“The West is rich, with many more resources at its disposal,” he continues. “It is time to launch the concept of the universality of humanity. Photography lends itself to a demonstration of this and as an instrument of solidarity between peoples.”

In 1994 Salgado left Magnum and set up his own agency, Amazonas Images, with Wanick Salgado. He worked on Migrations until the late 1990s but after that, he tells Hamilton, he had “seen so much suffering, violence, war and famine, created by the large-scale movements of country people to the cities, of those fleeing armed conflicts, genocide or natural disasters, that I had started to lose my faith in the future of humanity”.

His response was to start work on Genesis in 2004, an eight-year project he described as “a visual ode to the majesty and fragility of the Earth”. Including lyrical landscapes, close-up images of animals, and portraits of peoples living in greater harmony with the planet, this project represented the most important eight years of his life, he tells Hamilton. “I saw probably the most beautiful, the most interesting, parts of this planet – the most incredible relations between the parts of this planet and the species that live on it.

“I hear everywhere in the world people saying that we are the only rational species on this planet – but it’s a big lie,” he continues. “A huge lie! Each species is rational. I discovered this photographing at very close quarters. They are as rational as we are. They love their babies, they love each other.” Later he adds that a lizard’s hand “is like a human hand, but covered in something like chain mail”.

It’s a view of animals that could be described as anthropomorphic, and this is not the only potential criticism of Salgado’s photography; throughout his career critics questioned whether his images aestheticise and objectify, most memorably Ingrid Sischy in The New Yorker in 1991. In her article Good Intentions Sischy writes of “the unrelenting application of the lyric and the didactic to his subjects”, and asserts that “Salgado’s subjects are too much in the service of illustrating his various themes and notions to be allowed either to stand forth as individuals or to represent millions”.

It’s a factor Hopkinson also brings up in her article for BJP. She references an ad campaign Salgado worked on for Silk Cut in 1988, for example, which was banned by the Advertising Standard Authority on the grounds that it misrepresented an ethnic minority. “That the depiction of Papua New Guinea tribesmen bearing a standard of slashed purple silk might have been a surreptitious manifestation of western neo-imperialism seems to have escaped Salgado’s fierce scrutiny,” Hopkinson writes.

Hopkinson also asks Salgado about depersonalisation in his images of the Brazilian miners, which she describes as showing “what look like millions of toiling ants endlessly fulfilling the curse of Sisyphus”, throwing into question the “vaunted dignity of humanity” in Salgado’s work. He’s genuinely perplexed, she says, remonstrating that: “It makes no difference whether I photograph one person or a hundred together, I know every one of those miners, I’ve lived among them. They are all my friends.”

It’s a moot point but also an insight into Salgado’s working method; he didn’t aim for a distanced, anthropological perspective, and preferred to work alone to get closer to those he photographed. “Only by tendering yourself as defenceless as the people you photograph, entering their world as a vulnerable stranger, will they not only tolerate but welcome your presence,” he tells Hopkinson. “There’s no sense in which I am an anonymous voyeur: I live within the phenomenon I document.”

Salgado took a similar approach when making Genesis, sometimes quite literally getting close to the nature, animals, and people he photographed. “With some of these animals I got down on my hands and knees to be close to them, at their level for three or four hours,” he tells Hamilton. Sadly, longer-term Salgado really was vulnerable and living within the phenomenon – his death was caused by leukemia, traceable to a 2010 trip to Indonesian New Guinea on which he contracted falciparum malaria, which permanently impaired his bone-marrow function.

Salgado’s work remains, however, as does another important project – the reforestation of some 17,000 acres of land in Brazil, known as the Instituto Terra. Salgado grew up in a cattle ranch which had fallen victim to deforestation and erosion by the end of the 20th century; his father proposed Salgado and his wife take it over and, while at first the couple was reluctant, “Leila had the great idea that we could replant it and recreate the forest that had been there before,” Salgado told Hamilton.

“We sowed more than 300 species of tree, and as the saplings became trees, insects, flowers and birds began to reappear,” he continues. “In time the reforestation also meant the land could now absorb the water from flash floods and so the rivers and streams could flow all year long. And at last the fish and calmans came back too.

“Although we were amazed at how nature can fight back, we began to get worried about the threat to the whole planet. There is a strange idea that nature and humanity are different but in fact this separation poses a great threat to humanity. We think we can control nature, but it’s easy to forget that we need it for our survival.”

Sebastião Salgado 08 February 1944 – 23 May 2025.