All images © Savino Carbone

The Italian photographer spent years in Iraq focusing on its Shia communities and complicating the idea of ‘social Islam’

Iraq boasts a diverse and complex cultural landscape beyond the country’s inaccurate representations in the media – one which drew Italian photographer Savino Carbone in. Through his lens, he explores the deep-rooted traditions of Iraq’s Shia communities, revealing how religious narratives shape both personal identity and political movements.

Carbone, reflecting on his motivations for his work in Iraq, questions the canon of Western photography – the problems that come with being a documentarian in a foreign country, and he discusses the evolution of his project towards a humanistic angle, whilst finding the delicate balance between documenting history and respecting the subjects he photographs. From the busy and tired streets of Mosul to the glittering sacred shrines of Karbala, his work offers an intimate glimpse into a world often misrepresented in the West.

“I avoided contexts where violence could be exerted, and I chose not to impose it aesthetically either”

Dalia Al-Dujaili: What was your motivation for this project, and what is your relationship to Iraq generally?

Savino Carbone: I began developing an interest in Iraq alongside my academic studies in philosophy and social movements. In Italy, the memory of the U.S. invasion remains vivid, partly because Iraq, following the tragedy of the G8 in Genova in 2001, symbolised the end of a grassroots political movement centered around pacifism and social justice. So, for my generation, Iraq is a paradigm of contemporary warfare. In 2022, I decided to visit the country to visually explore the long-term effects of the conflict on the Iraqi population, who have been forced for years to live in a “heterotopia” that denies every process of mourning – be it personal, social, or political. Additionally, I needed to professionally challenge myself with something bigger, like the Middle East, as my documentary work had previously been confined to Italy.

DA: Why did you choose to focus on the Shia culture in Iraq?

SC: My initial research focused on Mosul and the northern regions of the country, devastated by the years of ISIS and the subsequent battle for liberation. However, upon arriving, I realised I risked repeating work already done by other authors. Yet, I immediately sensed a palpable frustration among the population, tied to the control of the predominantly Sunni city by Shiite militias. This was a story that deserved to be told. The tension stemmed from the political use of a specific theological tradition and the devotion associated with it. In Europe, we struggle to understand “social Islam” without falling into the trap of “fundamentalism,” as happened with the Muslim Brotherhood. This is even more true for Shiite Islam, whose image has been inevitably tainted by Khomeini’s 1979 revolution. A messianic religious narrative, rooted in an original martyrdom, easily resonated with a population as it lent itself to discourses of liberation and emancipation.

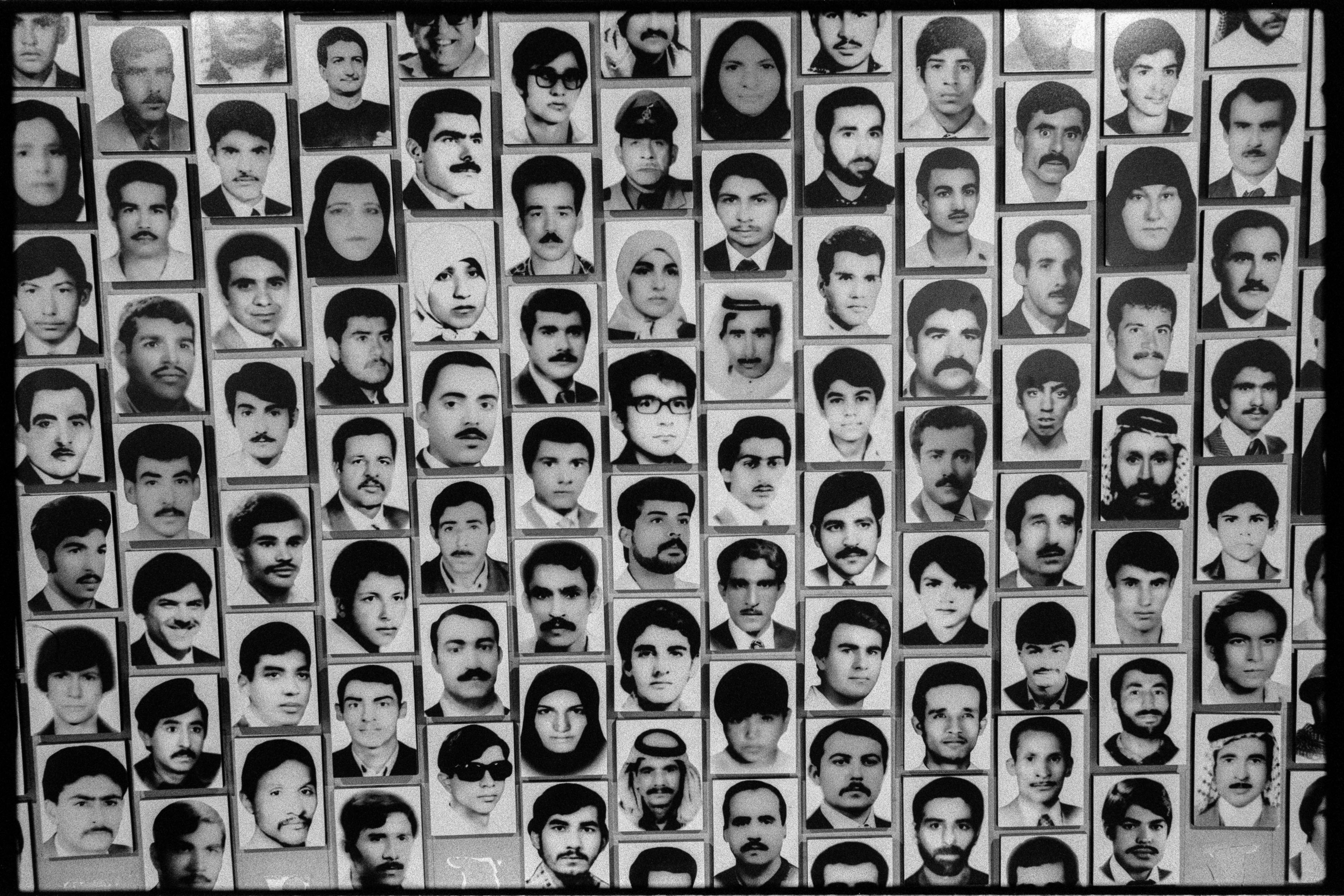

This was true under Saddam, during the U.S. occupation, and in the fight against ISIS. Exploring the power of such a narrative in a country that has struggled to find lasting peace since 1980 seemed fascinating and original, especially from a photographic perspective, which still seems anchored to the work of Gilles Peress (created in a similar but distinct context). During my travels, I pondered the evocative power of the Islamic tradition and how it formed the basis for the construction of an international network that is simultaneously religious, political, and military, with Iraq serving as its testing ground.

DA: How do you believe the project has evolved since you started it?

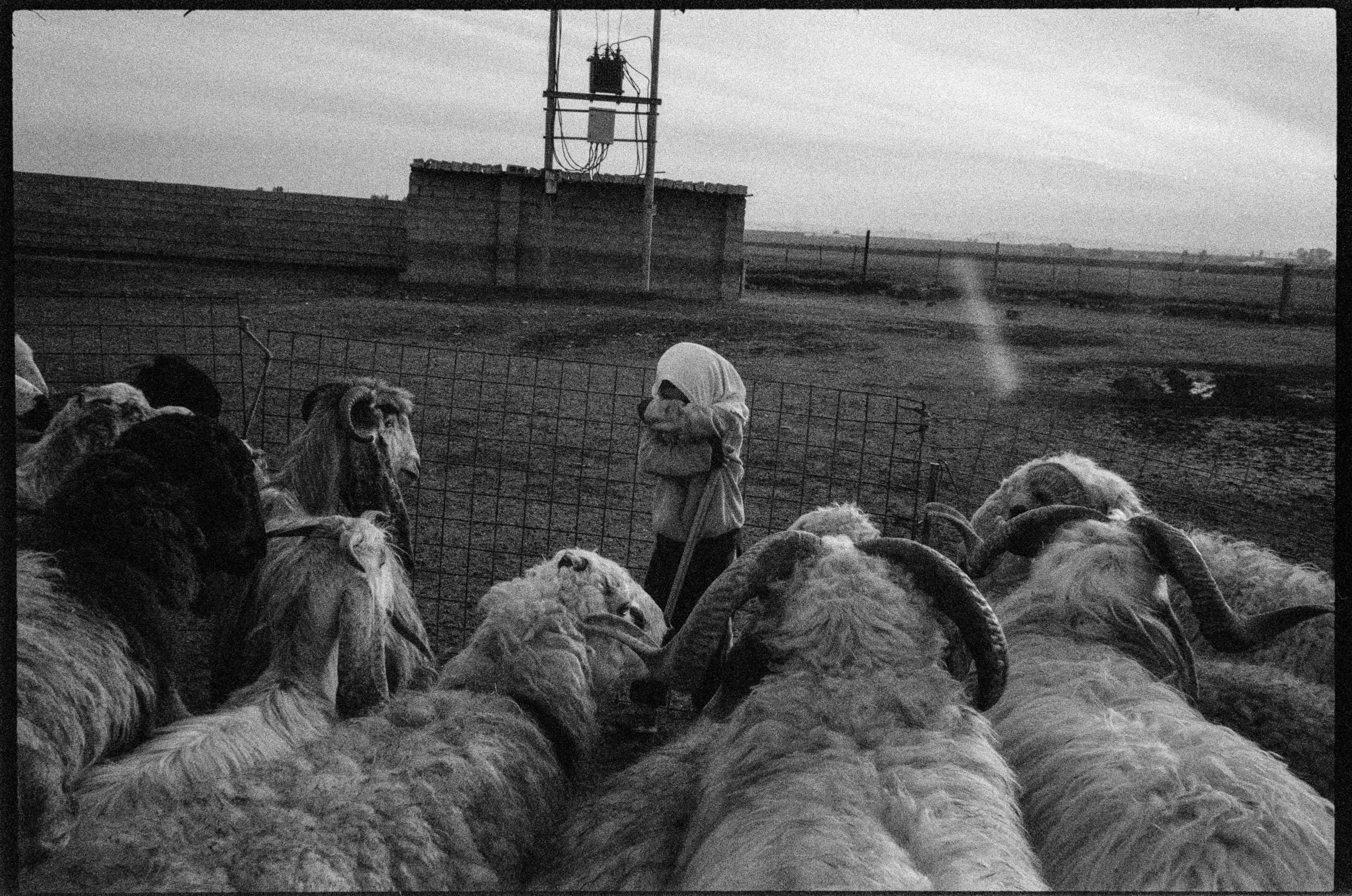

SC: For this reason, after a brief period in Mosul and a short mission in Kurdistan, I focused on the southern part of the country, from Baghdad to Basra, where the heart of the Shiite community lies, and the signs of this tradition are most evident. Especially in 2022, when the project was self-funded, I concentrated on communal practices around the shrines of Khadimya in Baghdad, and the shrines of Imams Ali, Abbas, and Hussein, as well as key sites in the recent history of Iraqi political shiism, such as Sadr City in Baghdad.

In 2024, the project was granted by the Italian Ministry of Culture and was produced by Camera a Sud Company, allowing me to return to the country to further explore these themes and document perhaps the most significant moment of this pietism, the Arbaeen walk. However, the war in Gaza and the involvement of shiite militias in the regional conflict made the work on the ground extremely challenging, especially in late July following the assassination of Ismail Haniyeh in Teheran. Despite the tensions of the past year, I was able to witness how political and military actors, who have played pivotal roles in Iraq’s history over the last two decades – from the civil war to the fight against ISIS – have used religious narratives for propaganda purposes.

DA: Tell me about the people you met and how they reacted to having their photo taken.

SC: Iraq is an incredibly welcoming country, and its citizens are curious about foreigners. I never had issues with my subjects; interactions were friendly from the start. The only moments of tension occurred, understandably, at checkpoints, where I struggled to explain my presence and especially why I was traveling with analog cameras and a lot of films. However, it was important for me to engage with the Iraqis who accompanied me on this journey, including academics from the College of Fine Arts in Mosul and some colleagues in Basra, to talk about not only the situation of the country but also our different aesthetic languages.

Generally, I wasn’t interested in gathering individual stories; my focus was on exploring a collective identity, so my interaction with subjects was somewhat limited. The most significant engagement was with the communal dimension during certain religious practices, such as those in Karbala or Al-Faw. I wasn’t trying to codify their spirit but to experience it.

I grew up with a certain photojournalistic tradition, which I find challenging to reconcile with, as it was born out of the major conflicts of the 20th century. Therefore, I avoided contexts where violence could be exerted, and I chose not to impose it aesthetically either. I preferred to accompany my subjects and then let them go, rather than inserting them into a narrative where they wouldn’t have a voice. I wanted to ensure that my work didn’t become another exercise of power, whether aesthetic or post-colonial.

DA: What are you focusing on now, in Iraq or elsewhere in the world?

SC: For now, I consider my work in Iraq complete. It has been exhibited in Italy (with the title “Don’t mess with the hangman’s rope”, from a Fadhil al-Azzawi poem), at di Mola di Bari Castle (South Italy), and will be featured in a book that will be out next Autumn. Currently, I am in pre-production on a project about the Balkans, focusing on the lingering ghosts of a conflict that Europe has yet to fully reckon with. Overall, I will continue to explore those memories that persist in quietly shaping our present.