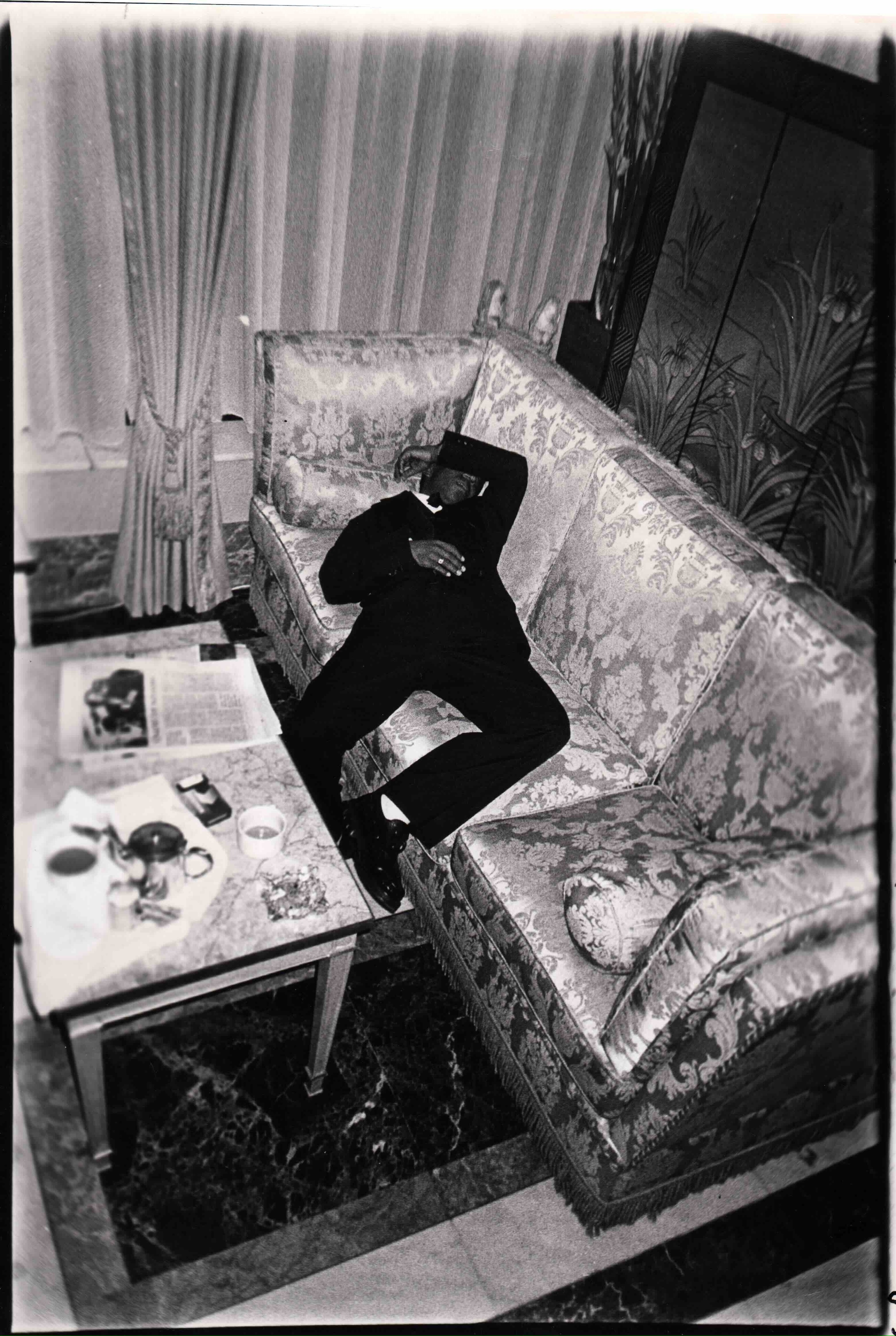

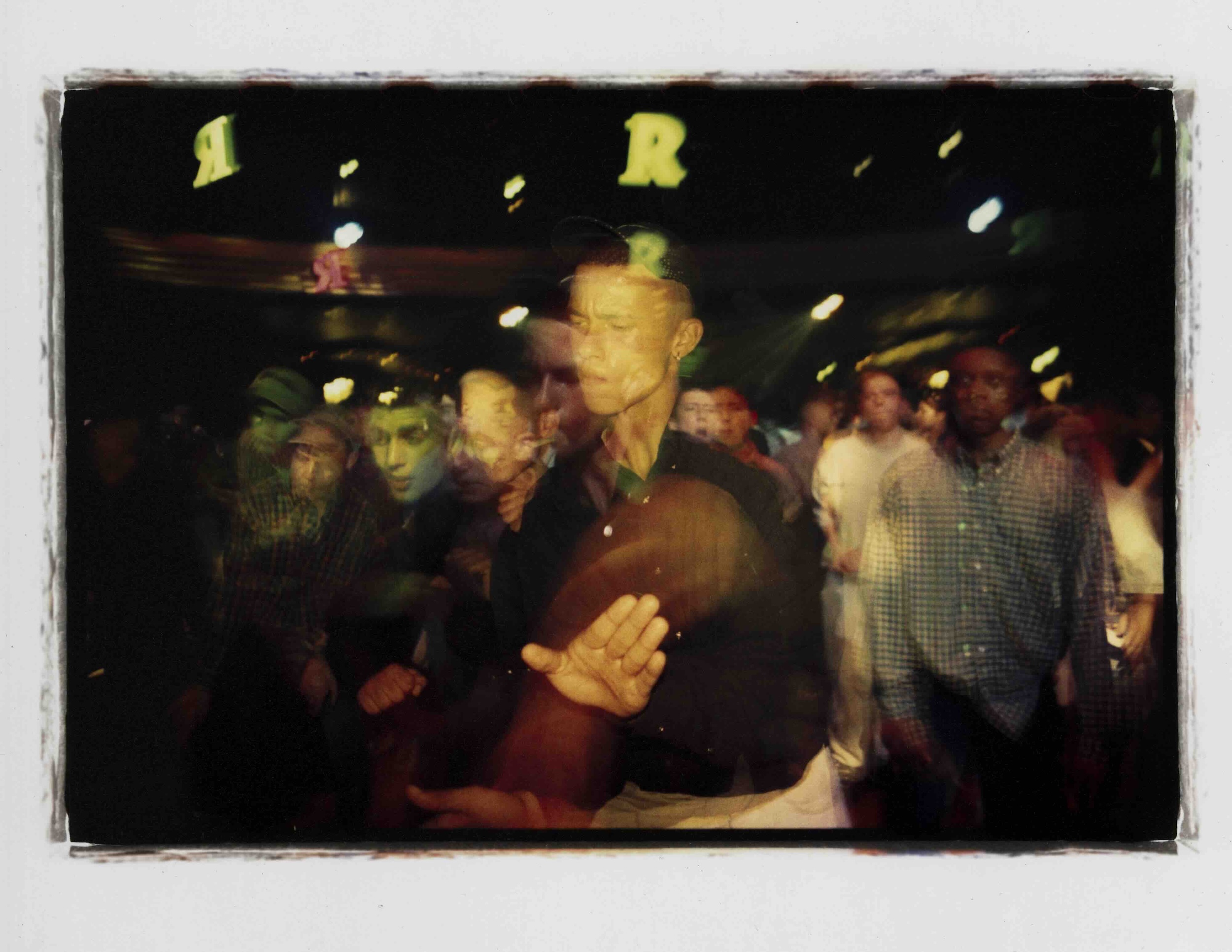

Above © Ewen Spencer

The Afropean author is back with a touring show, curating working-class photographers to present an alternative reading of class aesthetics

In 1992, Francis Fukuyama wrote The End of History and the Last Man, which argues that after the Cold War, history would end; “That is, the end-point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government,” Fukuyama writes.

Johny Pitts was interested in the symmetries between Fukuyama’s argument and photographic depictions of the working class. “[Fukuyama] captured the zeitgeist of the time and I think for the last 30 years, we have been living in this single economic and cultural space that’s dominated by western liberal democracy and capitalism,” Pitts tells me, expanding on Fukuyama’s thesis and the basis for his new show.

After Brian Cass at Haywood Gallery Touring read Pitt’s seminal book Afropean, he initially thought about Pitts curating Black photographers, “but the more I thought about the opportunity,” Pitts tells me, “I thought about some of my favorite Black photographers and I felt that their work was more interesting in a wider context.” After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989 – 2024 asks which images embody working-class life of the last 35 years, curating 26 working-class photographers of various backgrounds, with a heavy Black and Asian presence. Last year, the show visited Coventry, Southend, and Nottingham. This March it opens at Stills in Edinburgh.

“I think that’s what you get in this exhibition, the myriad ways that working-class people have persisted despite austerity, despite Thatcherism – they’ve found ways to still be creative”

“It seemed to me that during the 60s, 70s and 80s, you had uprisings, working-class solidarity, strikes, unions, things like the Greater London Council – all these organisations that meant that there was a strong working class, a strong political blackness that was going around. The visibility of all that seemed to end in the 90s. And with that I think that working class culture did change. There seemed to be no alternative to this way of doing things.”

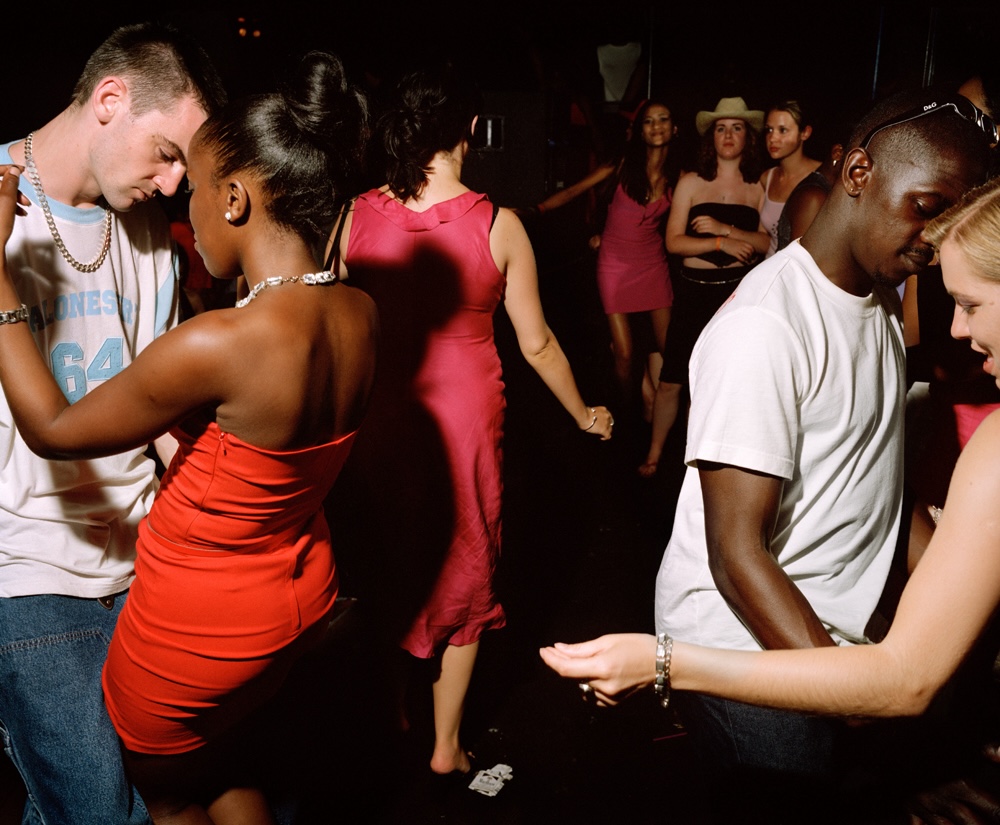

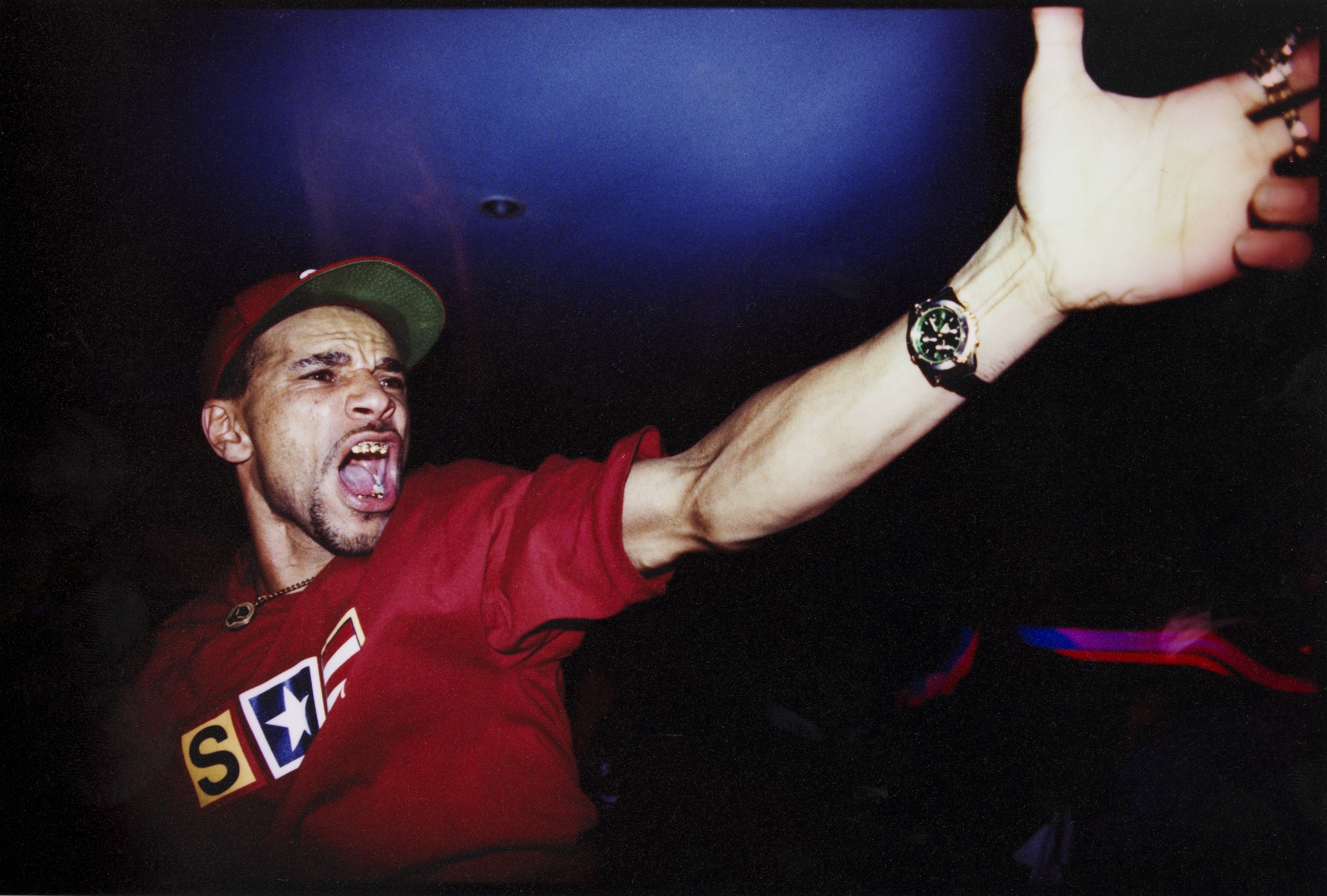

Pitts became frustrated with repetitive imagery of the working-class before the 1990s. Images by Tish Murtha, Chris Killip, Martin Parr and Paul Graham have become the most widely disseminated aesthetic of working-class Britain, but Pitts wants to ask what working-class has evolved into since then. “It’s the rise of consumer culture within working-class communities. It’s the rise of club culture. And then the new labour world which seems to signify there was no alternative vision for how working-class people could live. You get a completely different aesthetic to the 80s,” says Pitts, a period which the Tate Britain is currently shining its light on.

“Having that cut off point for the curatorial parameters of the show meant that I couldn’t myself get comfortable in those obvious lowhanging fruit names. It would be obvious to show Paul Graham’s work in the job centers in the 1980s, everyone who’s into photography has seen that work, and I wanted to force myself to find different voices and also deal with that rise of multiculturalism that was so often missing in those photographs. You’re either getting photographs of the Black community protesting or you were getting photographs of white people in unions and in steel works and miners,” says Pitts, noting the lack of new multiculturalism that began to take shape in Britain in the 90s and 2000s.

But it’s also difficult to present a show on the working class without fetishising its aesthetic. As has been tradition in the British music and fashion industries, for example, which has seen a gross appropriation of working-class visuals such as music videos shot on council estates and the consumption of working-class styles in clothing. Pitts tried to resist the glamorisation of working-class culture, including any kind of work “as long as it wasn’t poverty porn or culture safari through the working class from an external gaze,” he says. The photographers he curated grew up working class, “with very little access to money, with no network. I am myself included with that. So it was important to make sure that the practitioners themselves are working-class rather than just a depiction of what somebody thinks the working class should look through the fashion world.”

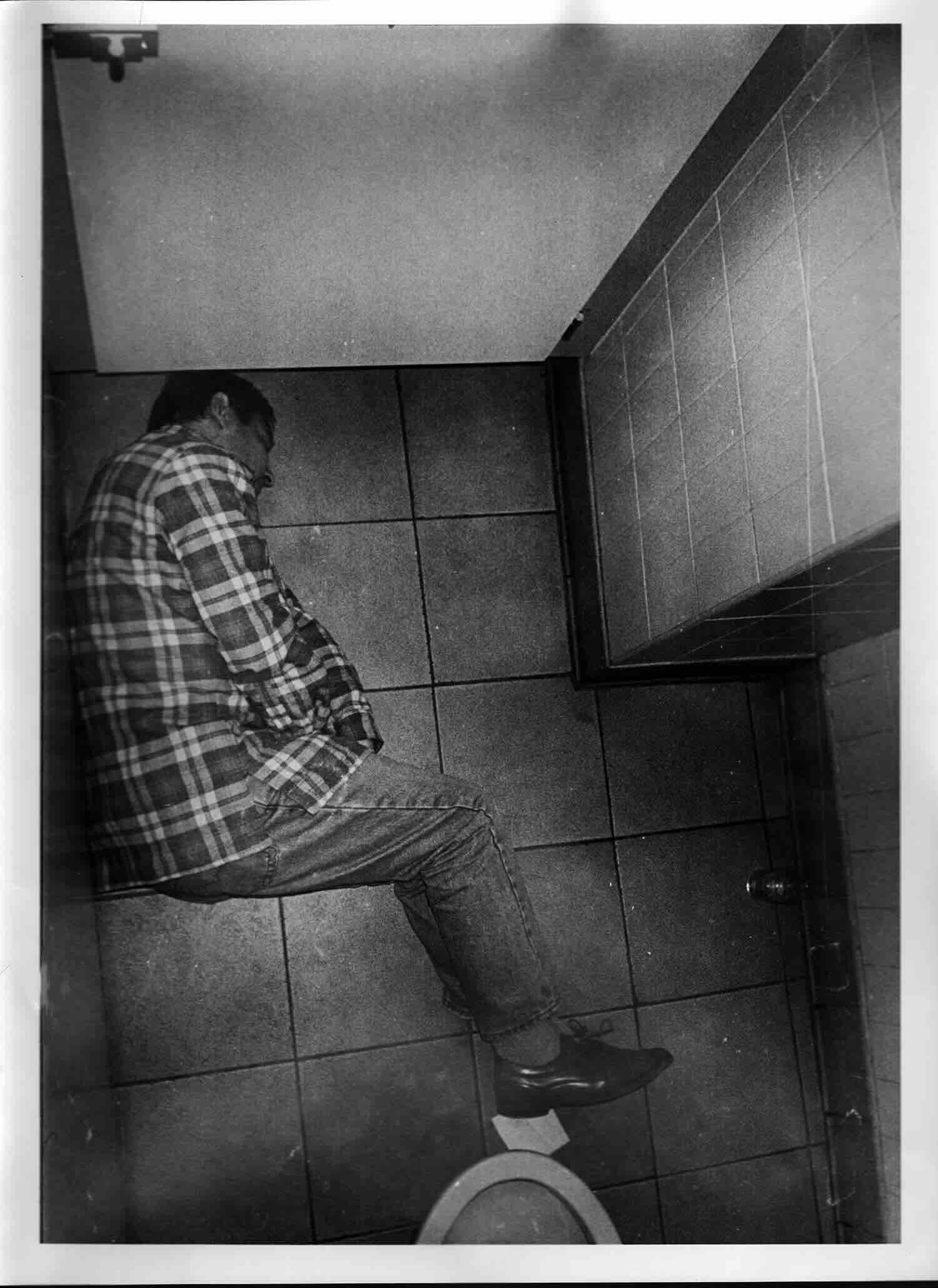

The touring show opens alongside a new book by Pitts, Afropean: A Journal, which displays a scrapbook, collage-esque assortment of notes, tickets, ephemera and vernacular imagery. Pitts sees the book and the show in dialogue with one another in the ways they present a “messier” representation of working-class culture. “What happens if you can’t go to school to learn these things officially, what kind of aesthetics does that produce? And is there virtue in that DIY aesthetic?” wonders Pitts. “There are [working-class photographers] who were going out clubbing and just happened to have a camera with them, and there’s an energy there and a rawness that I think is actually sometimes missing in traditional, classic documentary photography that we saw in the 70s and 80s.”

Highlighting photographers such as Eddie Otchere and Rene Matic, who focus on nightlife and spontaneous moments of joy and movement. Pitts observes that the work isn’t perfect, “the flash goes off where you wouldn’t expect it to,” for example, and that seems important to the curator within the documentation of the working class; for this reason “as I was putting the book together I didn’t want to make it too neat,” Pitts explains.

“I didn’t want [Afropean: A Journal] to look like a classic, modernist photo book for a coffee table. I wanted to show the kind of messiness of a creative working-class life and having to do two or three jobs to make [ends meet] and how the work sometimes spills into the photography and how the photography sometimes spills into the work.” For example, Chris Shaw, included in After the End of History, shot photographs whilst working as a night porter, showing a unique world at night unseen by man. Anna Magnowska, on the other hand, took photographs while she was working in a bar as a waitress.

“There’s also been a democratisation of camera technology,” continues Pitts. “The smartphone is the obvious thing. Everyone can take a decent photograph with a smartphone, but even compact cameras in the 90s got cheaper. So there was just a completely different aesthetic that began to emerge.”

Pitts grew up in a lower working-class area of Sheffield, “but we didn’t just sit around feeling sorry for ourselves. We’d make stuff happen. We’d go to illegal raves or we’d find ways to still be creative and connect and play, and I think that’s what you get in this exhibition, the myriad ways that working-class people have persisted despite austerity, despite Thatcherism – they’ve found ways to still be creative.”

Sheffield is also where, as Pitts reminds me, The Full Monty was filmed. “And I like that film. It’s funny and it captures a bit of where I’m from. But one thing that I can’t forgive it for is how you can film in my area and not see any Yemeni people or not see any Somali, Jamaican or Pakistani people. It’s unbelievable – they produce this view of Sheffield as this white working-class space. But for me, I know the reality wasn’t that.” After the End of History is an attempt at depicting the reality of today’s Britain organically, including images of Slovakian and Roma people by Artur Conka, the South Asian community by Kavi Pujara, and the diversity of youth on Britain’s dancefloors by Ewen Spencer. Whilst admitting it was amiss to not include a Scottish photographer, “this is very much not a London centric show,” Pitts stresses.