All images © Amak Mahmoodian

Using archive imagery, collaboration, extreme close-ups and staged photographs, the Iranian photographer has created projects that delve into portraiture while adding cultural and political context

A state of exile can be thought of as the unbreachable distance that forms between people and places. It is to be in existence away from your point of origin, often as the result of incompatible social, political or cultural positions that do not allow for the dissonant, messy, real nature of relationships, personal opinions and conflicts on a human scale. But exile is a space which, Amak Mahmoodian believes, can be temporarily circumnavigated through the dream world. In the unpredictable, exaggerated realness of dreams Mahmoodian, also living in exile, finds herself reunited with her family in familiar landscapes. There she can see their faces and relive the small details of their not-quite-physical beings for a couple of hours every night.

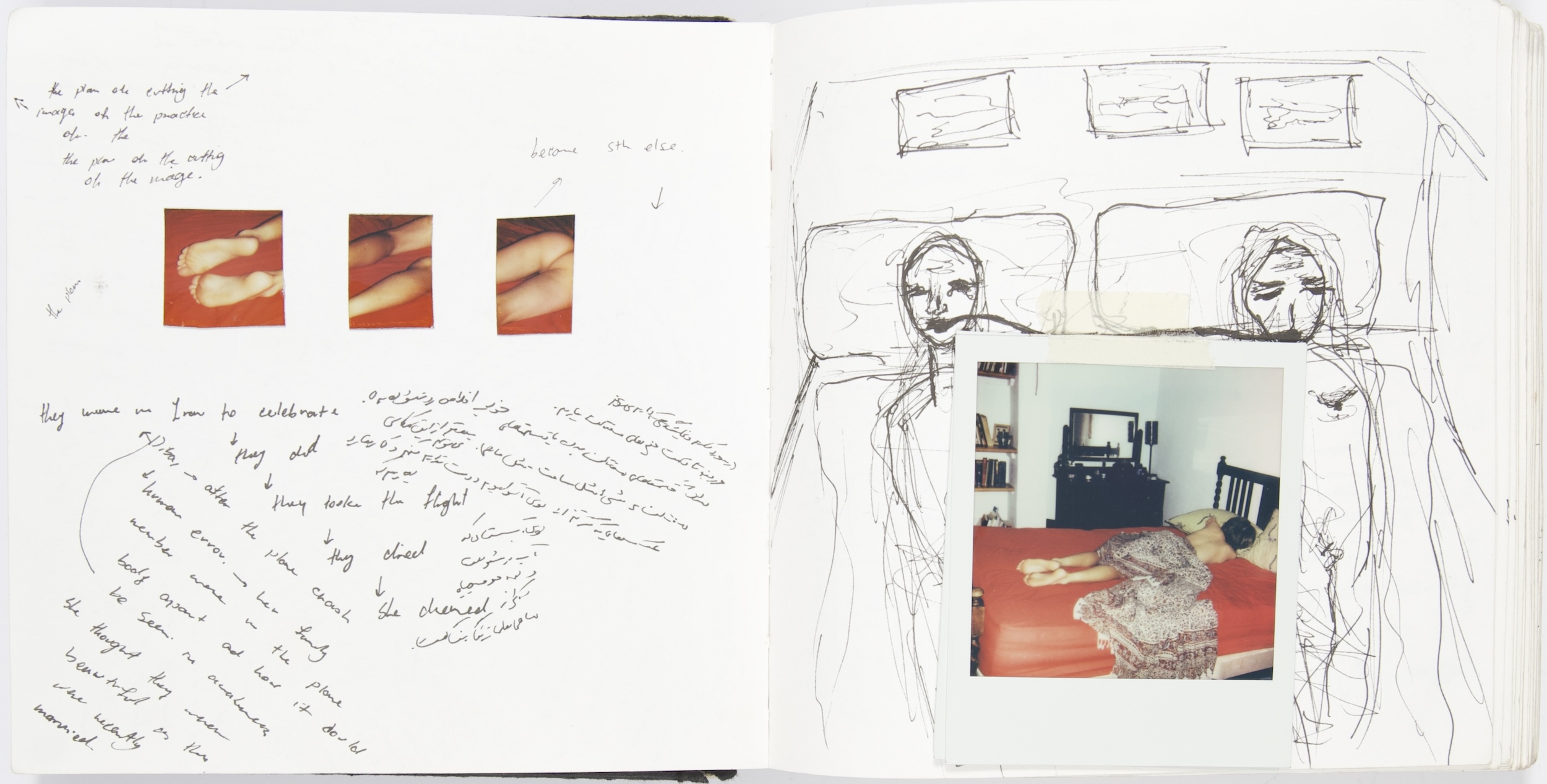

The title of her most recent project, One Hundred and Twenty Minutes, refers to the average amount of time we spend dreaming each night. Themes of escape, return and otherness are folded into this long-term project of personal storytelling, translation and metamorphosis. The project demonstrates the distances forced onto people, communicates the small and persistent aches gathered over time, and presents the large and devastating ruptures on interconnected lives. “Living in exile, it became the cornerstone of this project,” Mahmoodian reflects. What began as an informal sharing of dreams among a small group of peers became a collaborative, community-led project exploring this untouchable space of impossible reunion.

“The work is a response to the physical border which has been created by political leaders. We cannot change the circumstance, but we can change the perspective”

“Dreams are personal,” she continues. “When we are awake, we share moments together, but as soon as we close our eyes and we are asleep, we create a world which is absolutely private. You can let people come in or leave, and I love this life without borders. It is a response to the physical border which has been created by political leaders. We cannot change the circumstance, but we can change the perspective.”

An early job of translating for Iranian migrants as they arrived in England gave Mahmoodian access and insight to the recent journeys that people had made, how they saw themselves, and how they were seen in their new environments. She adds there was a sense of fear that the existing communities felt in the face of immigration. This prompted her desire to document people, and validate their existence in hostile spaces. At heart, One Hundred and Twenty Minutes is a portraiture project of invisible bonds and invisible people.

Mahmoodian’s sense of purpose was clear from the outset in wanting to portray people, to show immigration and its different layers without relying on typical, heavy-handed methods. Instead, we are presented with a body of work which introduces us to people’s inner lives, suggests a sense of their worlds and experiences, offers contexts to where this knowledge has derived from, and asks readers to interpret for themselves who is being witnessed.

The participatory project began with a small group of people in exile and led to dreams being recounted in the form of sketchbooks, poems and videos, slowly unfolding through a series of personal introductions, from one participant to the next, from Pakistan to Iraq to Russia and more until the project encompassed the stories of 16 people. The participatory nature also extended to the involvement of Multistory, a West Midlands-based organisation with a focus on community and connection which facilitated and offered support to the body of research Mahmoodian had compiled.

The slow process of documenting and recording their dreams began as a personal journey which was not immediately shared with Mahmoodian; once the foundation of trust had been established, the sharing began, as well as making introductions to others with similar stories and dreams. This became a network of interconnected experiences and memories of being far from home with Mahmoodian as their interpreter.

This role of interpreter and medium lent itself to photographing the participants with an intuitive and incisive approach. What defines a portrait? A visible face, an identifying feature, the intention to portray the reality of someone with an objective likeness? One Hundred and Twenty Minutes does not respond to these notions of a typical portrait project, however it deeply humanises the collaborators and recalls the other worlds in which they previously existed, through portraits which are both unreal and reflective.

Through parted curtains a diffused light falls onto a figure lying prone on a bed. The absence of a face or many identifying features is subtle yet intentional. The cropping, obscuring and masking of details all serve to guard the identities of the sitters. When faceless and nameless, they can fully inhabit and share these dreams without danger to themselves or the families they have left behind in the regimes they have fled. Exile has not allowed for full expression, but Mahmoodian has gathered and dispersed narratives that are articulate, insightful and specific to these lives and relationships explored throughout the collaboration. The portraits are an act of trust between photographer and sitter, and the force of the portraits is an indicator of the strength of these collaborative relationships.

The series of images are also a distillation of dreams in which anything can happen and different strands of life can co-exist. The portrait of the individual, veiled by another curtain, demonstrates this break in time and narrative. The figure cradles two newborn dolls in a pose reminiscent of virtuous, Mary-like statues. A disrupted state of motherhood is suggested by the presence of the children, potentially acting as placeholders for others who cannot be pictured here for reasons that are not shared.

The lightweight curtain is a barrier between the sitter and her surrogate children, preventing physical touch between them, though the chance for metaphorical reconnection remains possible. The second, heavier set of curtains can still encompass them in a final sweep that hides them from our sight, while bringing them into the same plane. This image demonstrates the many layers of meaning and remove that are at play in these real, and often painful relationships. We can only begin to imagine who and what has been left behind in this life, and what solace the dreams can bring.

The portraits share space with images in this series which possess the abstract, ungraspable quality that often occurs when recounting dreams in the light of a new day. They are like portals to a place that changes the nature of its fabric at every occasion. The images also demonstrate the transition from sleep to wake and renewal. A snapshot furtively taken from the back of a moving car, view partially restricted, lending a sense of hurried escape, or the whorl and creases of a navel mirrored in another image of the bark of a tree, all now impossible to decipher. The series offers fragments, imprints, impressions, moments of people re-enacted and caught up by Mahmoodian.

The abstract nature allows for all the dream threads to tangle together into one narrative, returning to Mahmoodian’s urge to move towards a life without borders. The weaving together is also shared in the collaborative process which became so all-encompassing that Mahmoodian started to dream the participants’ dreams, temporarily becoming them in these third spaces. Mahmoodian noted that, in dreams we do not often see our bodies, that we are fully within ourselves and the point of view is first person. In making portraits of these dreams, a third-person perspective has been added, and it becomes possible to see both body and context in the same view. This, combined with empathy, makes these stories and people more visible.

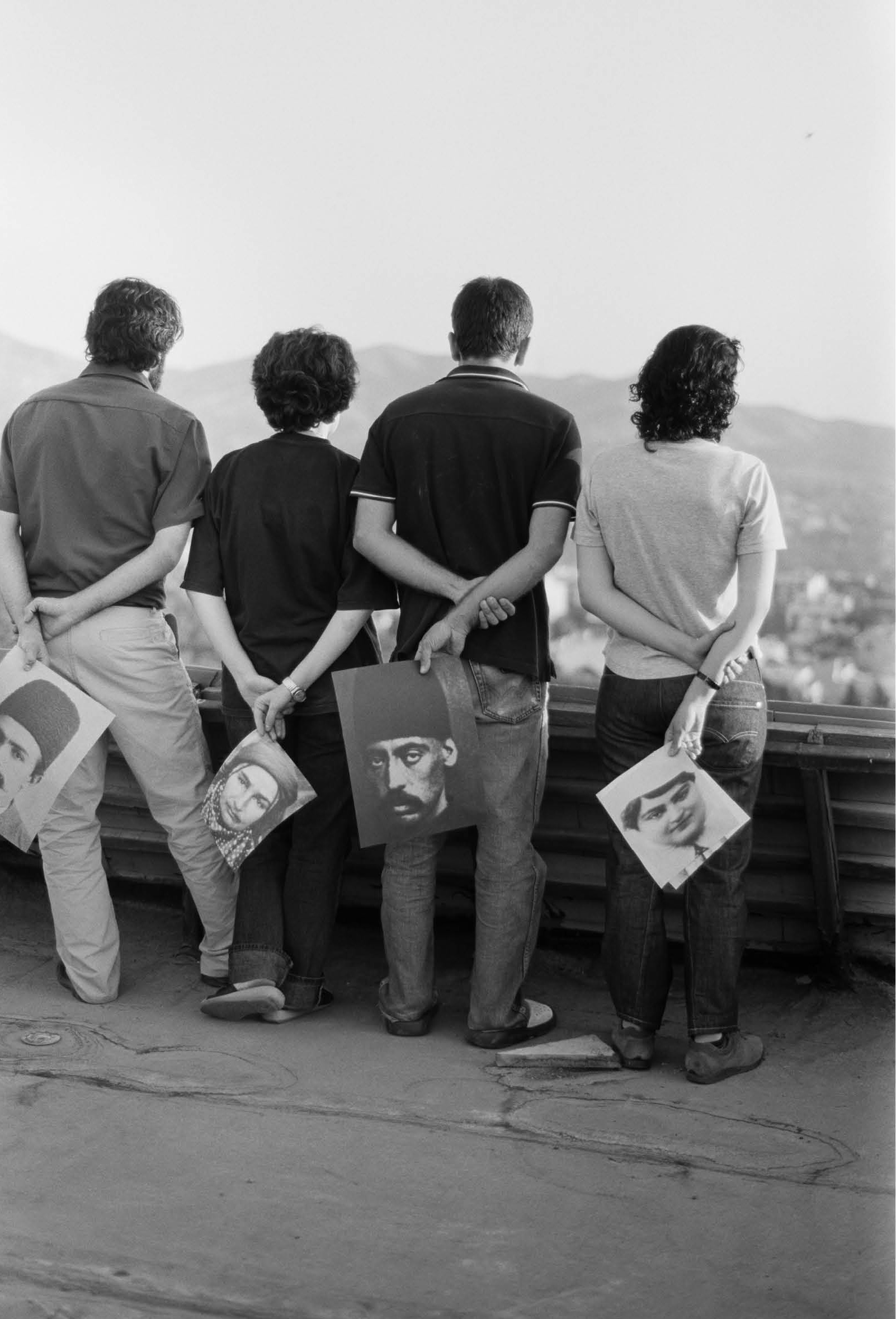

This line of empathetic, subsuming storytelling runs throughout many other projects by Mahmoodian, which also feature people living at a remove either physically or across time. In Zanjir, she draws upon a set of portraits taken from a museum’s archive in central Tehran to stage an imagined conversation between herself and the Persian princess and memoirist Taj Saltaneh. The two artists are separated by decades, Mahmoodian born over 40 years after Saltaneh’s death, yet they work in tandem to present their poetry, portraits, memoirs and archival images within the context of a contemporary world.

The faces within the portraits allow us to see through fresh eyes, to encounter events for the first time which did not exist at the time the portraits were made, and to enable a type of comparison between before and after. Zanjir, meaning chain, is a link between past and present identities, binding, weighing down, but also lashing together. The project highlights the tangible outcomes of Saltaneh’s activism, outspoken feminism and criticism of the monarchy which was headed by her father. Placing the archival images in a contemporary setting demonstrates the steps taken to lead to the present tense. To achieve this, Mahmoodian has overlaid and performed with the portraits in ways that further close the gap of time.

Mahmoodian has not taken these portraits, but she has created possibilities for them. New narratives are shuffled and shared out in different settings and then rephotographed. In recapturing and re-presenting them, she lends the sitters bodies and temporarily makes them physical. They take up space at the table, a relaxed moment captured in their borrowed jeans, casual tops and everyday jewellery. They are sat in public parks, held by hands which first frustrate and then merge with the view of the contemporary sitters holding them in place. These are double portraits consisting of archival portraits and present-day life, and their overlapping shapes.

The ordinary domesticity lends the images a family album aesthetic. Groupings of possible siblings, cousins, parents and extended family sit, lean, crouch, mimic and are reflected, either in bodies of water, in mirrors, or in the reprinted images which act as the temporary face of the sitter. Alongside this aesthetic are multiple exposures which speak to these many perspectives and positions. A shimmering hand waves a path through the air in one image, while in another a man – Mahmoodian’s father – pivots, turning to face several directions while being photographed, as if contemplating the many possible directions one can take.

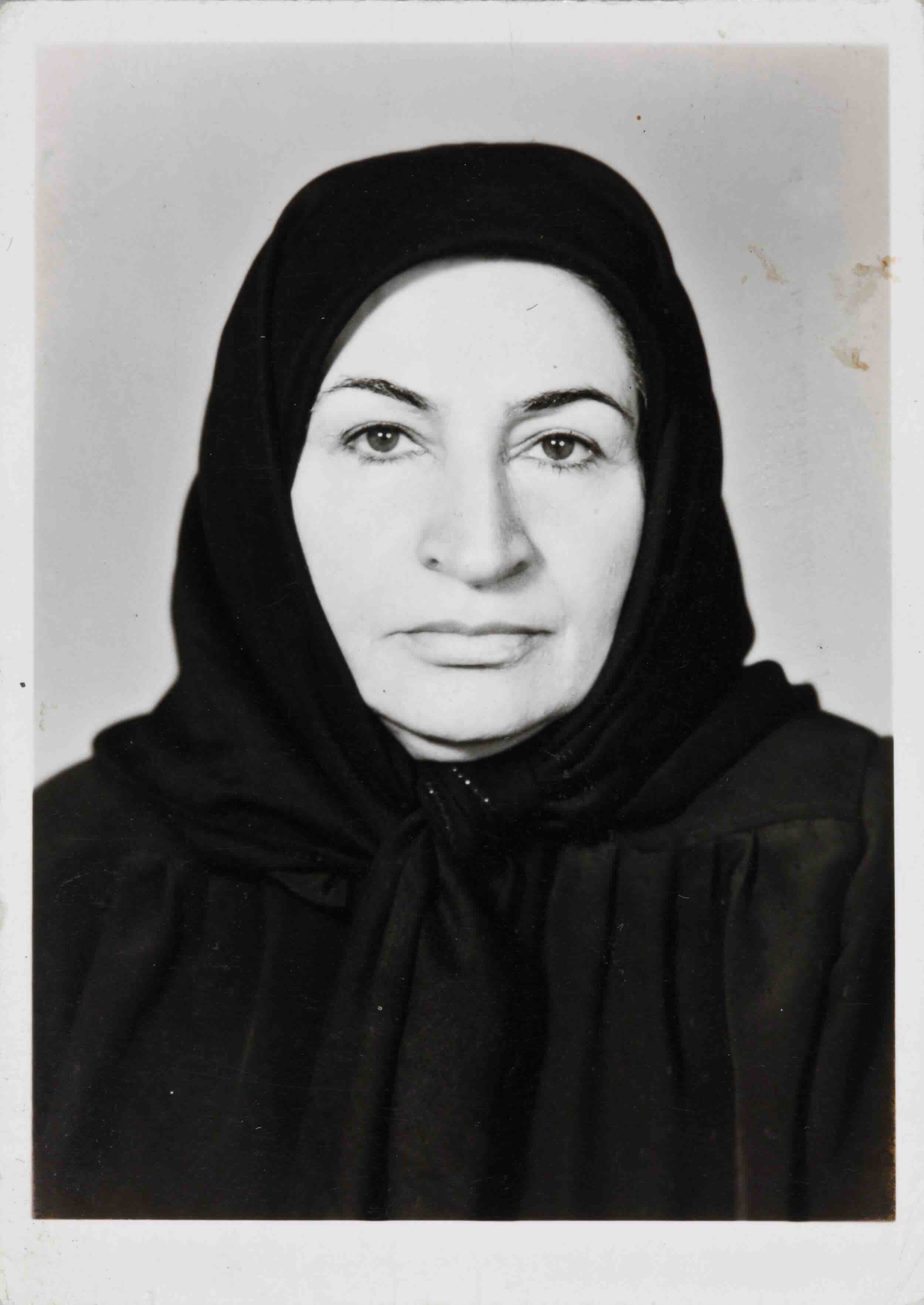

Mahmoodian explains that many of her projects are located within or taken from archives, with the photograph becoming a document of what happened and what remains while demonstrating this process of reinterpretation. This continues in Shenasnameh, in which the documented objects are a series of ID photos. There is yet another personal thread throughout which guides viewers from initial idea to delivery.

A Shenasnameh is an Iranian birth certificate and features a photograph which requires periodical updating; while waiting to renew her photograph with her mother, Mahmoodian could not help but note how the differences between herself and her mother’s identification images had been flattened, and how the similarities had been exaggerated.

This smoothing and cloning effect is the result of Iran’s now mandatory wearing of the hijab, a head covering for women. The compulsory nature removes people’s choice and leaves what can be seen on the surface to be an unyielding template for women to fit into. The scarf made not just Mahmoodian and her mother appear to be interchangeable but also removed the defining surface features of the women portrayed in these collected portraits. The Shenasnameh also features the ID holder’s fingerprint and it is really here, in these unreadable, indecipherable patterns, that women can emphasise their individuality and character.

The scale of the image, the size of a passport photo, something small and easily tucked away or forgotten, also contributes towards a sense that these women have been designed to be insignificant. It is left to the small details to define the sitters within the images. The shape of the eyebrows, the angle at which the woman presents herself to the camera, the warmth of the black-and-white images or the choice or availability of a colour portrait, the creases and stamps all serve to differentiate the women in a way they are not able to achieve for themselves in everyday, non-photographic settings. “Some protests are silent,” Mahmoodian observes.

September 2024 was the two-year anniversary of the death of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old who died soon after being arrested by the Guidance Patrol for allegedly not wearing her hijab correctly. Iranian police deny involvement in Amini’s death but her passing became one of many galvanising moments in a fight against dictatorship which has spanned decades, this instance notably women-led. This recent wave of protest has adopted the Woman, Life, Freedom slogan from other long-standing, women-led protests and demonstrations.

Mahmoodian explains that this is another unifying moment for communities facing repression and violence within and beyond Iran, and that in spite of the criticism many have faced – including Mahmoodian – there is a dedication, almost a devotion, to this revolution.

The notion of the obscured portrait is approached from another perspective in the Gereh series. Here, Mahmoodian leans in with the camera and creates portraits of sitters who all engage in the ritual of tying their headscarves as a small flourish of their personalities. The family connection we can now expect to see in Mahmoodian’s projects derives its inspiration from her grandmother, whose own knotted scarves Mahmoodian began to see sported by strangers on the streets of Tehran.

Mahmoodian spoke with people and collected stories and created an inventory of scarves and their wearers. Again, the political and social are tied into this project, and the small acts of personal defiance and visual compliance are put forth for us to see as a recurring motif. The women are young, old, tattooed, made-up, jewelled, or heavily layered. Some knots are tight, unlikely to need retying throughout the day, others are pinned, while some are loosely draped or hang free entirely.

Of note are the three portraits which do not feature knots at all and are fascinating in their use of nature and natural materials to mimic the presence of a knot while removing the headscarf altogether. A bunch of grapes is both fun and provocative in its sparse covering of the body. The lightweight mimicry and draping, the complementary colours of the deep green leaf and red hanging material demonstrate how easily and seamlessly the scarf can be replaced, while introducing ideas of beauty and rebellion. Again, these portraits reveal only half a face yet possess a sense of individualism, and acknowledge a series of personal decisions that have brought these women before the camera.

A thread which runs throughout Mahmoodian’s work is the desire to find and rehome the lost and the irreplaceable. Mahmoodian achieves this through inviting several perspectives which look out, look back, and look beyond the single experience to create empathy and understanding through photography. Without resorting to nostalgia or creating a shrine to those no longer here or unable to be fully present, Mahmoodian has approached the passage of time, memory and people with a lightness and an affinity which runs throughout her collaborative approach. Her portraits are centred on identities that are veiled but still revealing in their nature.

Mahmoodian cleverly makes use of cultural constraints in informing her projects, creating portraits which ebb and flow in their reveals. The sense of a person, their personality, experience, lives and connections are documented in the details of Mahmoodian’s portraits. The collaborative storytelling, the images reimagined through their contemporary connections, the double portraits, the half portraits, the close-ups, all contribute towards enabling understanding of how identities are shaped within political landscapes, and the impact and importance of documenting these acts and these faces.