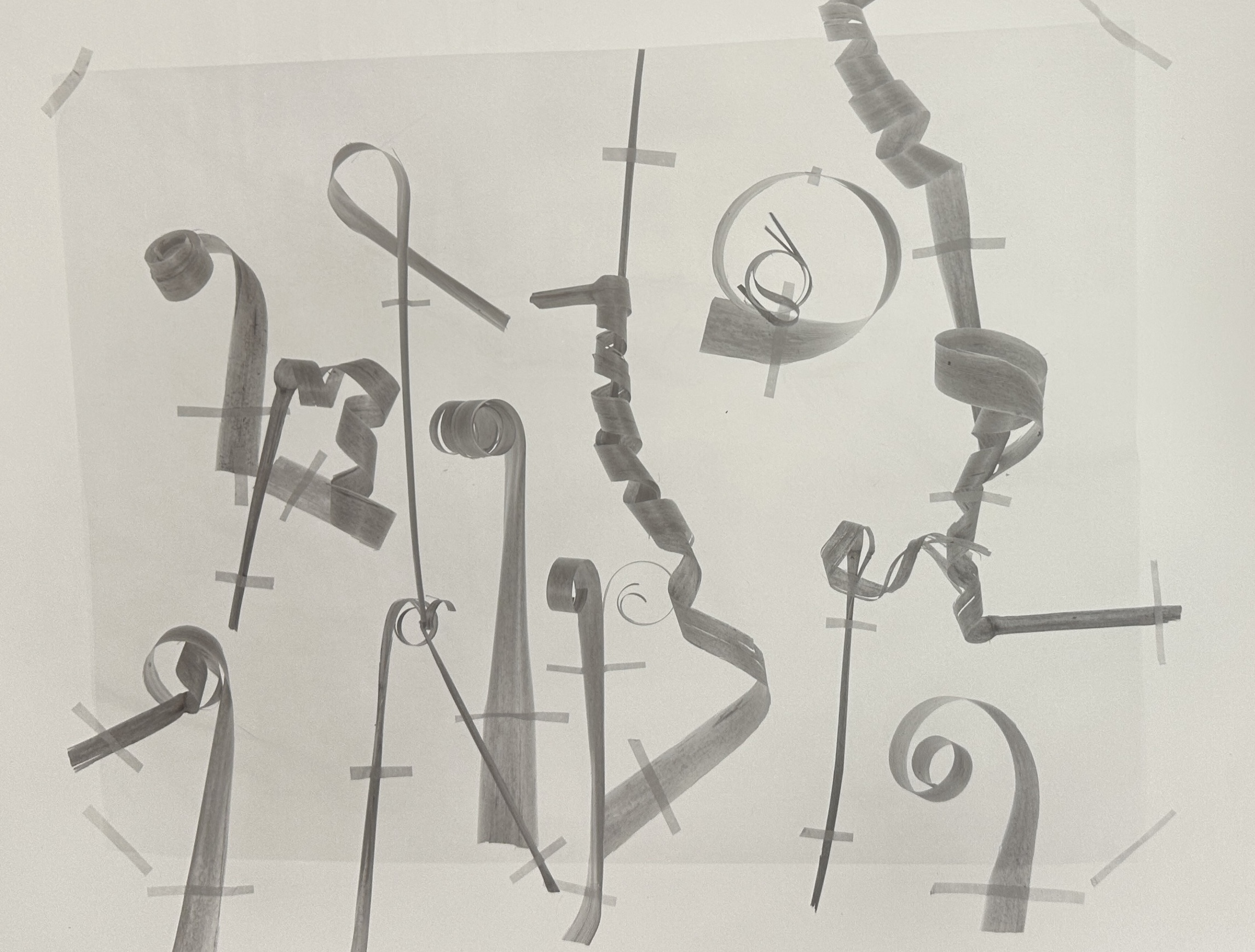

Mutations No.6, 1992 © The Estate of John Blakemore, courtesy Centre for British Photography

Celebrated landscape and still life photographer John Blakemore died on 14 January, aged 88. His friend and colleague Paul Hill pays tribute

Time plays tricks with the memory, but I think it is about 50 years since I first saw a photograph by John Blakemore. It was a nude in long grass that I thought was made by French photographer Jeanloup Sieff, much in vogue in the 1960s and 70s and known for wide-angle images of women. Looking back it is obvious this image was part of the transitional period between John’s documentary work, made in his home city of Coventry, and the meditative landscapes and exquisite still lifes he became renowned for in the latter decades of the 20th century and early years of this century.

When we both started work on the joint Creative Photography diploma course – he at Derby Lonsdale College of HE and me at Trent Polytechnic, Nottingham (now Derby University and Nottingham Trent University) – he sported a hipster-type beard and favoured denim jackets. I mention this because people think of John as a guru and gentle sage with long hair and beard, who always wore a fisherman’s smock and open-toed sandals. Many followed this bohemian fashion, but no-one carried it off better than John.

“His introspective approach reflected a movement in British photography that sought to use the medium in a more meditative way”

– Paul Hill

This persona came with an ever-increasing interest in Eastern philosophy and tantric practice (his brother taught yoga in the West Country). But John was not an aloof mystic or guru. He had a sharp, acerbic wit, but was also very shy. I remember him telling me that when he started teaching in Derby, he wandered the corridors at the Kedleston Road campus summoning up courage to face his first class of students.

This will surprise those photography students and workshop attendees at my Photographers’ Place in the Peak District, who clung to his every word as he talked eloquently about his work and sensitively critiqued their photographs for hours. His introspective approach reflected a movement in British photography that sought to use the medium in a more meditative way. Nature and the landscape were the leitmotifs. Spirit of Place was replacing a moment frozen in time. However, from time to time the black dog descended and you would not hear from John for a while.

I knew he would emerge when asked to give a talk about his work or run a workshop – which we did, often. John was not a self-promoter. But when someone opened the door and offered a platform, he came alive and entranced his audience with deep philosophical insights and immensely useful tips on how to improve photographically. He also possessed great curiosity and an impressive intellect. An example of this came when Derby offered him a sabbatical in the late 1980s and, instead of using the period to work on a new project, he enrolled on the MA Film Studies course at the University of East Anglia.

His renowned large format work surfaced following time spent in Wales in 1968, unsuccessfully running a cafe with Penny (his second wife) after the breakdown of his first marriage. Influenced by the Transcendental Movement and the work of American photographer Minor White, John returned to Wales and the Mawddach Estuary, where he used the natural world to make emotionally deep black-and-white images that were wonderfully gestural and metaphoric, about ideas not things.

During mentally challenging periods later, he often took nature indoors and made large format photographs that beautifully chronicled the life cycle of cut tulips in and out of vases, and arranged thistles and pampas grass still lifes that reminded me of Roger Fenton’s fruit and flowers prints made 140 years earlier.

Like many photographers of that postwar era, John stumbled on photography before pursuing it professionally, seeing the seminal Family of Man exhibition in the pages of Picture Post while he was doing his National Service as an RAF nurse in Libya in 1956. He recalled in John Blakemore: Photographs 1955–2010 (Dewi Lewis, 2011): “I saw photographs not as speaking of sameness but of difference. Of disparities of wealth and poverty, of war and peace.” He immediately ordered a camera and revelled in the excitement of looking through its lens.

Many see John as an artist who uses a camera, but I always think of him as a photographer who made art. This is not a semantic conceit; it defines a particular empirical practice that is camera-based, where the maker thinks and sees photographically and focuses on making the final print the event, rather than a record of what is in front of the camera. John made his landscape or still life prints with great, almost fetishistic concentration on craft and immaculateness. He was a consummate fine printer, rewarded by transmitting the sensitivities of his seeing into a tangible form.

It was an intensely personal journey as the photographs are emotional and evocative – and an escape from domestic problems and relationship difficulties. From time to time, he came to stay in my caravan in the Peak District and went out alone every day with his trusty MPP 5×4 and tripod. “To be alone in the landscape was a release, a return to the pleasures and pursuits of my childhood which had been lost to me,” he said.

John had left school at 16, going against his parents’ wishes to work on farms in Shropshire, my native county. He would talk about working with horses under the shadow of the iconic Wrekin, a hill near what is now Telford. Up until that time he had been a city boy. He was born in 1936 into a house without books, but became an avid reader obsessed with birdwatching, drawing and painting. He was influenced by his grandfather who had been a carter (someone who transported goods by cart). Perhaps that is why he always headed for the stables when he came to visit me.

On one of those visits he came with a handsome young man in his twenties, one of his two sons from his marriage to first wife Sheila. He had not seen him since the youngster had been a child and part of the reconciliation was visiting his photographic world. John was not a mystic in my experience, though he was mysterious. But if you want to discover this complex, gifted and generous person, you need only look at his photographs.

John was married to Sheila and Penelope and had two long-term partners, Catherine and Rosalind. He leaves behind three sons, Jay, Paul and Matthew, and two daughters, Gita and Orla. An open celebration of his life will take place later this year.