© Ana Margarita Flores

Holding Space at 10 14 gallery features several projects which shine a light on interdependence in global communities

To hold space is to welcome in; to say that you are safe and among friends. It is a feeling that is present in “diasporic communities across the world,” photographer Tirtha Lawati tells me, adding that: “It has always been significant for me to ‘hold space’ or create environments where we can represent our community and celebrate our identity.” Lawati is part of a group show which explores the act of Holding Space, presented by Thursday’s Child curators Daphne Chouliaraki Milner and Ashleigh Kane, alongside four other artists exploring global and local frameworks of support: Ana Margarita Flores, Sophie Stafford, Raajadharshini, and Kirk Lisaj.

Other than the theme, the images, exhibited at 10 14 gallery until 16 January, are united by form and sensibility too. There is a familiar warmth in every image, and though the images celebrate community and the bonds that locality brings, the images are somewhat quiet in their meditative, intimate and oftentimes stillness.

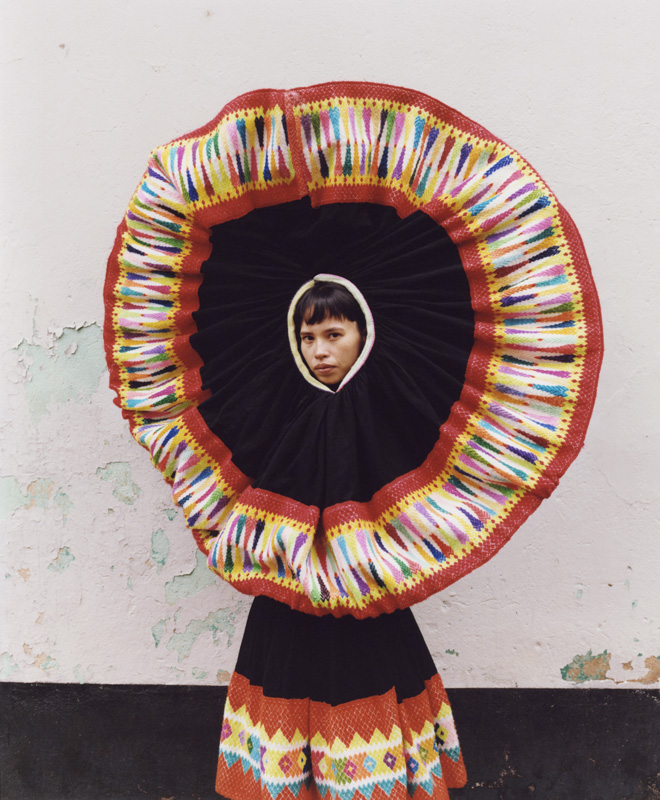

In Flores’ series Donde Florecen Estas Flores, for example, we meet the Andean women of the photographer’s native Peru. One woman stands for her portrait with a baby on her back; it’s a type of strength one only finds in mothers. In another scene, two women fill the frame, one laying down on the grass and another standing in the background, as they pose stoically and stare into the lens. “Growing up away from Peru, I always felt a strong yet distant connection to my roots,” Flores tells me. “This project became a way to bridge that gap and engage with my culture on a more personal and artistic level.”

“It’s in times like these that we must remember the power of community and care… Holding Space celebrates all the many beautiful ways we show up for one another”

– Daphne Chouliaraki Milner, co-curator

The project, which translates to “Where These Flowers Bloom”, compares Andean women to flowers, “symbols of beauty, resilience, and growth in often challenging environments,” explains Flores. The matriarchs of her family were ultimately the inspiration for the project; “including them, as well as myself, in the project became a love letter to them, allowing me to reflect on my maternal lineage and our shared connection to our Andean roots,” she continues.

The rural women from the Sacred Valley of Cusco are artisans and members of women-led craft collectives, “working to preserve traditional Andean practices while adapting them to contemporary life,” Flores tells me. “They play essential roles in their families and communities, often as leaders, caretakers, and creators.” Following the shoots, Flores would ask for the women’s feedback, meaning that the series was a vehicle for Flores to hand over agency to these women whilst allowing her to reconnect with her own heritage.

For Raajadharshini, the relationship between people and water in India, “where water bodies serve as essential hubs for community life,” she says, became the inspiration for the series Emergency Light. Growing up and living in Tamil Nadu, India, Raajadharshini became acutely aware of the effects of climate change, especially on water levels and accessibility. “I vividly remember the water crisis in Chennai, where the water levels in the city’s main reservoirs reached their lowest point in seven decades,” she explains. “This drought, ranking as the fifth lowest recorded in 74 years, brought unimaginable challenges to the city. In my own home, we had to adapt by storing water in large buckets and tanks, converting our dining room into a makeshift storage space.”

Emergency Light, a reference to the light device used when electricity cuts out, depicts locals gathering at bodies of water, forming relationships to one another encouraged by the shared desire to be close to this natural element. “Growing up amidst a visible crisis shows us how resourcefulness and shared effort became vital tools for survival,” says Raajadharshini. “From repurposing our dining room to store water during droughts to celebrating electricity’s return with our neighbours, these moments of connection were integral to our ability to cope with systemic failures and environmental hardships. I want to highlight how even in the face of overwhelming adversity, we have always found ways to make life happen. It’s sort of a reminder of how collective strength is both an act of survival and a profound form of connection.”

In diaspora, members of a dispersed community find one another. Lawati’s documentation of the Nepali diaspora in the UK is a collaborative effort with Nepali stylists exploring “the emotional landscapes of young people navigating life between two worlds,” says Lawati. Far From Home is a direct ode to the adaptability of those who carry dual identities and the “informal frameworks of support within diaspora communities-family, friends, and cultural traditions that help us navigate our dual identities,” continues the photographer.

By reimagining Nepali traditions which informed previous generations, Lawati examines what he calls “the invisible threads that connect us to Nepal, whether through memory, language, or shared experiences.” The photographer, himself of the Nepali diaspora, portrays the ways in which support and interdependence often rely more on the emotional bonds between people which transcend borders and geographies.

Working with a smaller group of artists, Kane explains that the co-curators wanted to ensure “a diversity of perspectives and experiences in order to do justice to the notion of holding space. We wanted to really examine what this could look like and the different ways that communities show up for one another,” she tells me. Sifting through Thursday’s Child large roster of artists, Kane and Milner consulted with an expert panel, including Gem Fletcher and Lillian Wilkie, which helped them to ultimately shortlist the five artists included.

“We live in precarious times, and there are many valid reasons to feel angry, scared, and hopeless about the challenges ahead – for humanity, for society, and for the planet,” adds Milner. “But it’s also in times like these that we must remember the power of community and care.” For this reason, Holding Space became a method for the creatives involved to celebrate “all the many beautiful ways we show up for one another.”

Flores, Lawati and Raajadharshini are all continuing to expand their respective bodies of work, and explore new projects too. Whilst Raajadharshini is hoping to work with individuals in unique and often overlooked occupations, such as the several “dying handicraft clusters in India,” Flores hopes to secure funding to continue her project, and to print and gift the images to the women involved. She’s also hoping to curate an exhibition in Urubamba, Cusco. And Lawati is keen to return to Nepal to explore the skate and music scenes in Kathmandu, Nepal, “hoping that eventually, a book will come to fruition.”