© Billy Barraclough

The self-taught photographer’s project Kash Hamam celebrates an ancient tradition, despite the vilification of its players played out against local social stigma

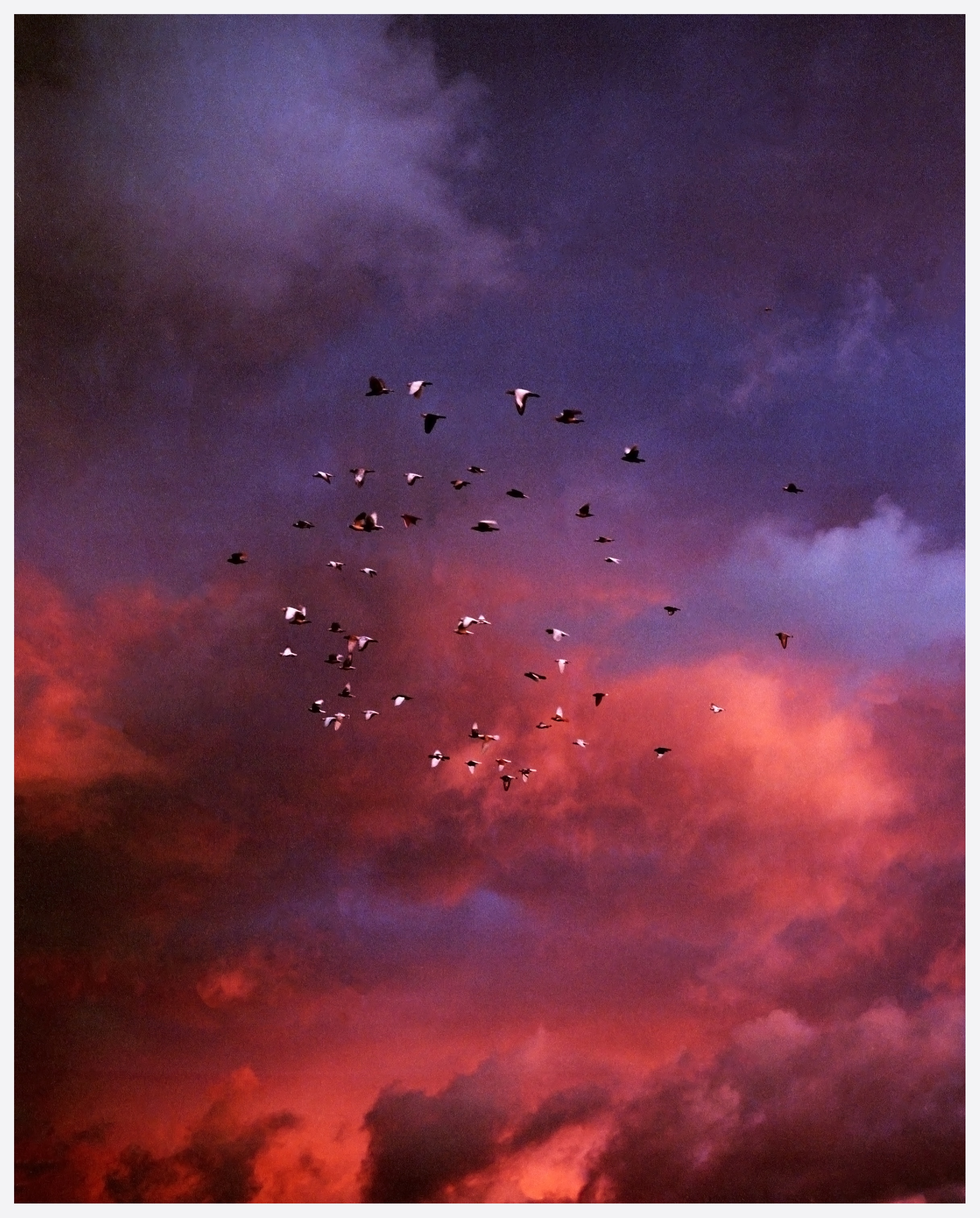

Kash Hamam is an ode to Beirut’s elusive rooftop pigeon keepers and the ancient art they practise. For Barraclough, this journey began in 2016, when he first encountered the “pigeon wars” that drift, unseen by most, over the rooftops of Beirut. That year, Barraclough was living in Beirut, working with a nonprofit that supported Palestinian and Syrian refugees. During his time off, he roamed the city’s streets and alleys camera in hand, drawn by the hum of daily life.

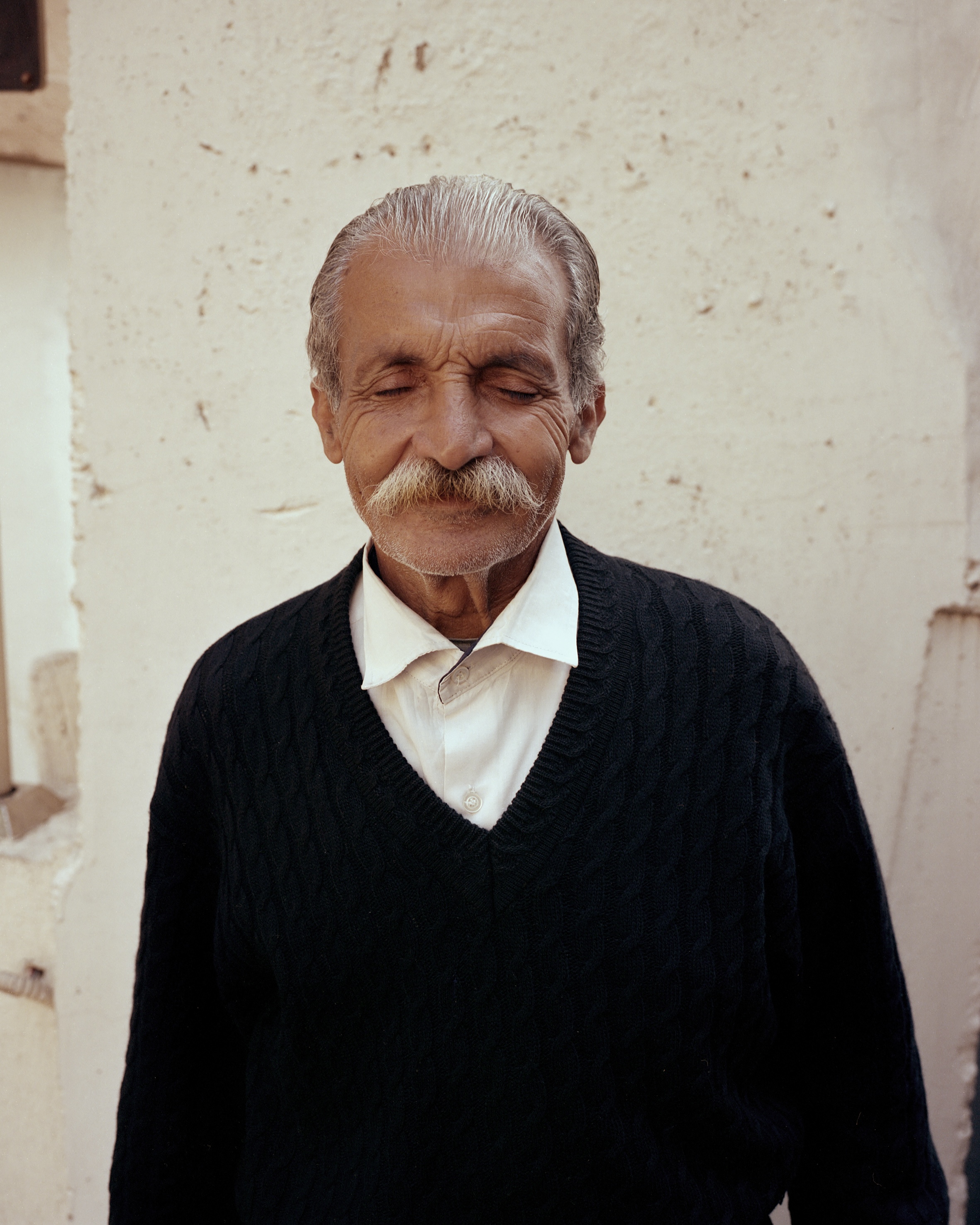

One evening, he stopped for falafel at a small kiosk, where he met Mohammed, a pigeon keeper with a profound love for his birds. Mohammed invited Barraclough onto his rooftop, where his homemade pigeon coops were perched, offering a sanctuary of calm above Beirut’s lively streets. There, Barraclough witnessed his first Kash Hamam, an ancient tradition in which the goal is to lure and “steal” neighbouring pigeons. He was transfixed.

“Mohammad began to orchestrate them by whistling and waving sticks through the air. It was the first time I’d witnessed the act of flying pigeons in Beirut and as we sat there watching the birds, Mohammad began to explain how much love he had for them, what flying them each day brought to his life, and the history of the game of Kash Hamam.” Barraclough met five pigeon keepers in the city between 2016 and 2018, and then returned in 2023 to try to reconnect with them and any new flyers that he met.

“I really wanted to try to explore the complex relationships pigeon keepers had with one another, their birds, but also the rest of Lebanese society”

Kash Hamam is a practice deeply embedded in Levantine culture. With over 200 pigeon keepers across Beirut, it’s a game and a lifestyle that has been passed down through generations. This pigeon war requires not only a keen understanding of pigeons’ homing instincts but also a deft hand at strategy. As Barraclough observed, each keeper cultivates unique techniques, carefully-crafted feed, and tricks designed to attract a neighbour’s birds. It’s an artful dance between tradition, skill, healthy competition, and camaraderie.

Kash Hamam is a portrait of pigeon-keepers who are isolated yet devoted. Pigeon keepers are often seen as outcasts, and sometimes vilified by Lebanese society. A long-standing law bars pigeon keepers from providing legal testimony, “They’re slandered as thieves, liars, and criminals,” says Barraclough. “Both physically and politically separate from the city, the men and their lofts share an intense relationship of love that continues despite the hardships that come with keeping birds. I really wanted to try to explore the complex relationships pigeon keepers had with one another, their birds, but also the rest of Lebanese society.”

Kash Hamam is Barraclough’s second major project in Lebanon, following his earlier series, I Trust in God, which quietly brings Lebanon’s layered sectarian landscape to the surface through quotidien imagery. The roots of Barraclough’s connection to Lebanon trace back to his late father, a writer and photographer who worked for Oxfam and Medical Aid for Palestinians. “I always knew about my father’s love for the region,” Barraclough reflects. “It felt natural to establish my own connection.” As he worked with an NGO in Lebanon, Barraclough began to deepen his understanding of the country’s intricate social fabric, a journey that ultimately translated into a desire to capture Beirut’s people and their stories.

The gap between both series is thematically not so different, though Barraclough’s style has matured and evolved. Nevertheless, he says he remains committed to a style rooted in the raw honesty of medium-format photography – a technique he taught himself. “It was a pretty free but failure-ridden approach, which definitely had a certain charm to it,” he recollects.

As Beirut and South Lebanon face mounting challenges under current Israeli bombardment, Barraclough has chosen an image from Kash Hamam to fundraise for Lebanon through the Eyeuna Initiative. The photograph depicts two young boys in Bourj Hammoud, watching pigeons soar between apartment blocks. For Barraclough, this image has become a symbol of his hope for Lebanon.

“Lebanon is a country that gave me so much and made me feel so eternally welcome, comfortable, excited and happy,” Barraclough says. “It’s a beautiful place that is currently under extreme pressure and the number of displaced people in such a small nation is horrifying. I hope this image and the other images in the fundraiser can begin to contribute towards supporting displaced people across the country at this moment.” The pigeon in flight, a recurring theme in his project, has long served as a symbol of peace. Here, it serves as both a tribute to the country and a call to action.