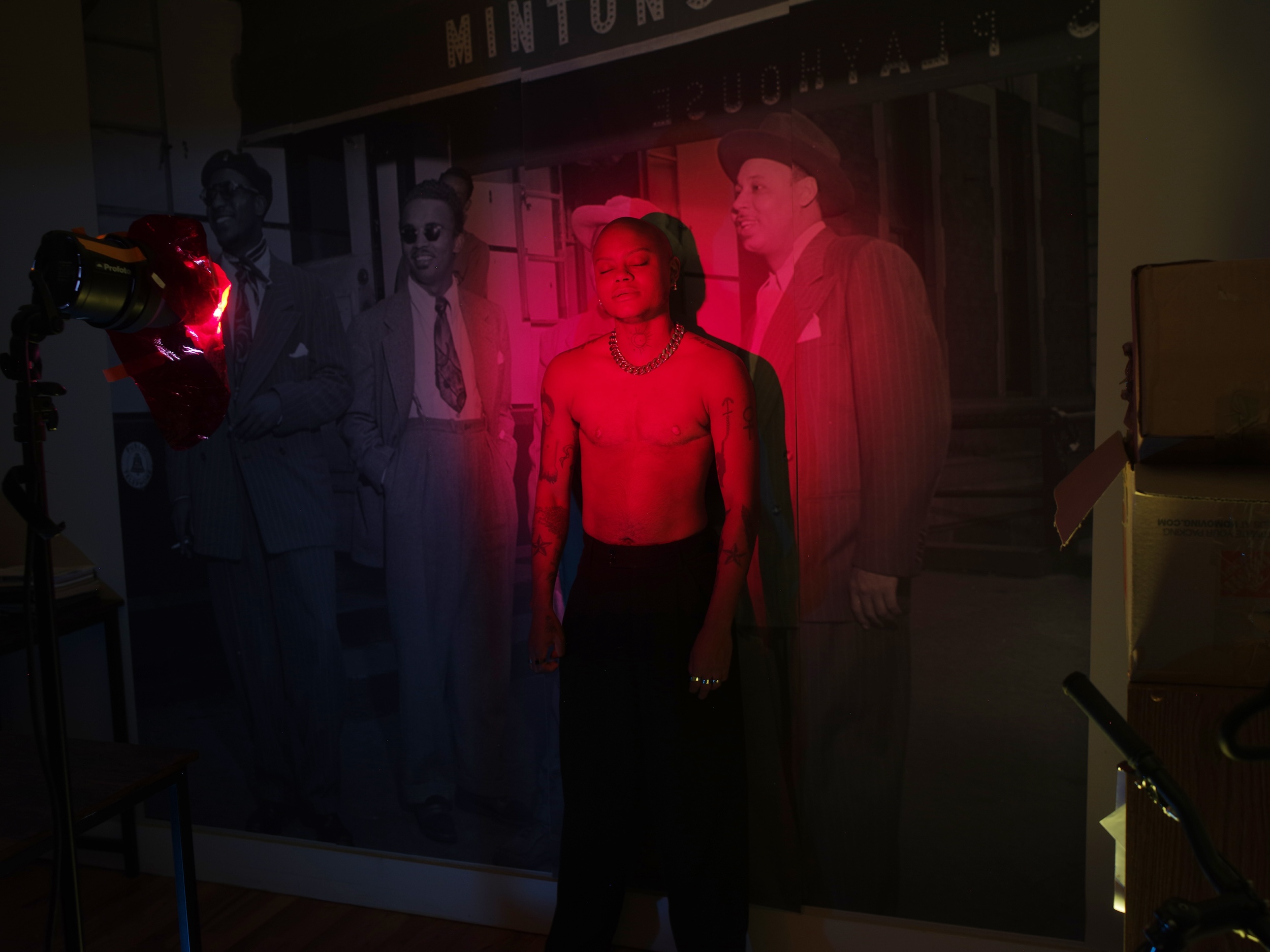

Ellington, Crown Heights, 2022 © Avion Pearce

The photographer is at play with the boundaries that confine both their lens-based practice and the socio-political context of their subjects, finds Matilde Manicardi

Their lids half-closed, mouth relaxed, and with the overall expression of someone immersed in an intense dream, Ellington stands against a wall-sized backdrop showing musicians in suits outside Minton’s Playhouse, the legendary Harlem jazz club. Their shadow seamlessly aligns with the profile of one of the suited men, making it hard to distinguish where the fictional image ends and the flesh-and-bones body begins. A tripod’s red light washes over the subject, serving as the only source of illumination; there’s a thrill of magic in the room. Ellington’s portrait appears in photographer Avion Pearce’s In the Hours Between Dawn, an ongoing series documenting the queer and trans community of colour’s ever-evolving relationship with the artist’s hometown of New York City. “For those of us who cannot indulge / the passing dreams of choice / who love in doorways coming and going / in the hours between dawns”, Audre Lorde wrote in her 1978 poem A Litany for Survival, inspiring the project its title.

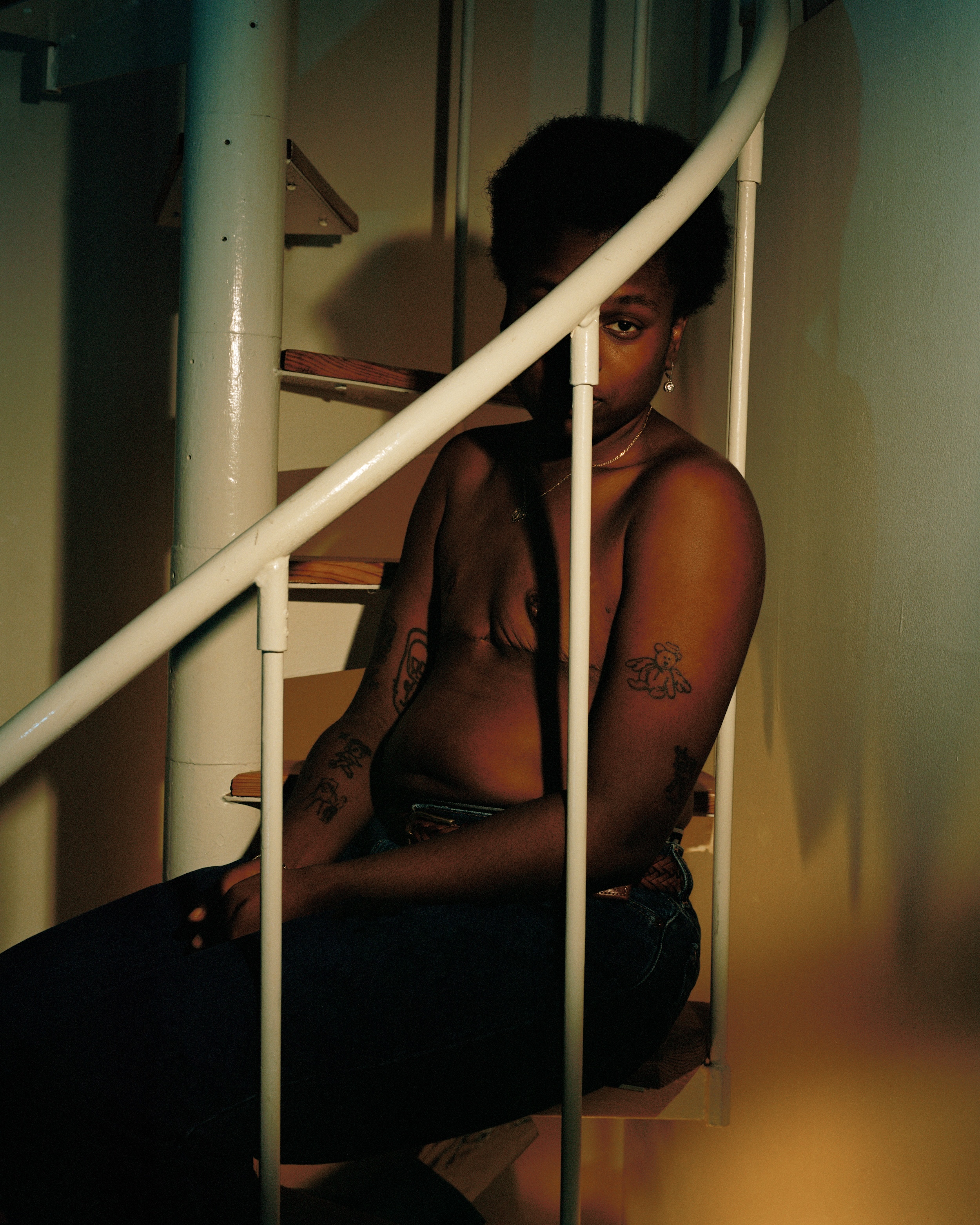

Through manipulating light, shadow, and focus, and utilising staged environments, props, and found objects, Pearce delves into the complex relationship between photography and truth. By creating worlds and narrating scenes that may or may not have happened, they examine photography’s role in constructing queer histories, capturing both the seen and the felt. Born in Flatbush, New York, to Guyanese parents, Pearce grew up in Long Island before returning to Brooklyn to study photography at the Parsons School of Design, a passion they nurtured from a very early age. After working in commercial photography and advertising, Pearce pursued an MFA at Yale, culminating in the 2024 Aperture Portfolio Prize. During their master’s, Pearce frequently travelled back to New York, where they now live and work, documenting life in their Crown Heights community. “I experienced a lack of representation of the beautiful, creative and brilliant people I see regularly, who are very much part of the city. I felt, and still do, the need to keep recording”, Pearce tells me.

Interweaving bodies, time, and place, Pearce captures their reciprocal influences: despite the ongoing struggle to survive the city’s economy and the country’s political environment with a tense upcoming election in November, the subjects portrayed continue to actively transform the city, infusing it with their own magic. “I want the work to reflect both survival and the desire to thrive”, Pearce tells me. A second image of Ellington, taken a year later, captures them in full shadow, revealing only the faint growth of facial hair, the subtle movement of their shoulders, and the glint of a golden chain. “I denied the viewer the exact description of them to make certain qualities stand out”, the photographer adds. By obscuring the rest of their features, Pearce emphasises the value of wearing that specific piece of jewellery, choosing to withhold a full depiction and moving away from the precise exposure and timing typical of traditional photography.

Stepping back from the more common strands of straightforward and self-evident queer image-making, Pearce’s portrayal of their queer community in Brooklyn aims to add nuances to the pursuit of being seen: Is visibility automatically good? “That body of work is essential and urgent”, the artist tells me, “but I believe that given our historical moment, we have to think carefully about our relationship to the complexity of visibility, and the belief that the straight photograph is the only solution. I am constantly negotiating this as I find alternative ways to make portraits, photograph space, and make images that have an emotional resonance”. The surge in attacks on the trans and queer community in the United States, backed by the strengthening of the European far-right, amounts to a crisis of trans and queer rights. In this political climate, a deeper reflection on what’s at stake in visibility is a fair concern.

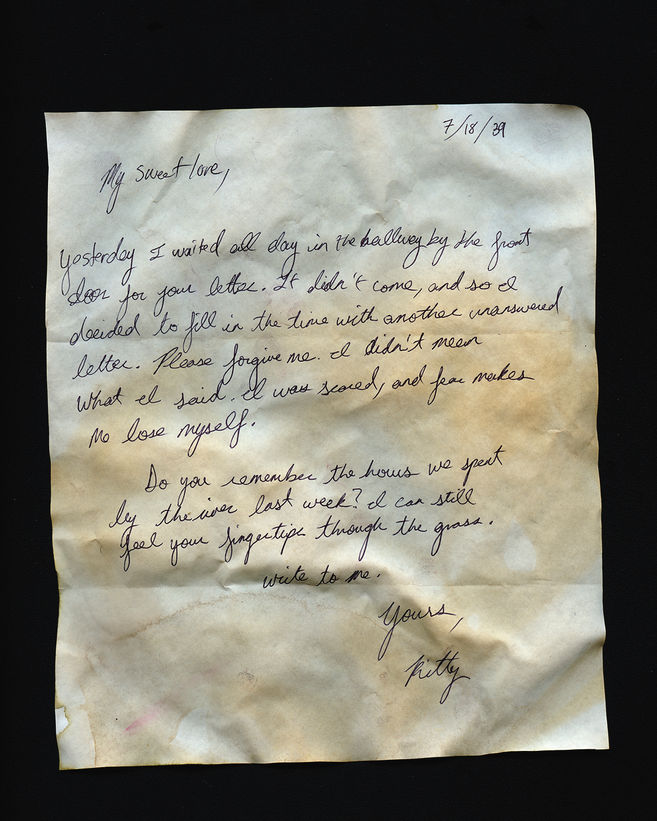

Beyond the wall-sized poster and the chain in Ellington’s portraits, Pearce’s visual realm is populated by costumes and found objects, which they use to layer narratives building upon these items as powerful signifiers of queer identities. “I’ve always been obsessed with how important objects are preserved and presented”, Pearce tells me. “I want to see that sort of treatment, that preciousness, applied to queer history”. By incorporating still life as prominently as people in their work, Pearce reintegrates forgotten objects of queer life into visual history, making a vital contribution to the long overdue material archive of lost queer histories.

The very existence of these objects is a testament to the fragments of stories that survived institutional attempts to erase queer memory throughout Western history, from public local and national archives to cultural conservation sites and productions. For the majority, those stories left no traces. This opens up a state of limbo; stories that could have been but were never documented, leaving us to wonder if they ever truly happened. Because a community’s social consciousness builds on its accessible past, these stories risk falling outside the collective memory. Unless, of course, someone intervenes in the archive, recreating what once went undocumented.

Between archival research and fictional narrative lies a space for reimagining. It’s New Orleans, 1939, and a makeshift cottage on the Mississippi River becomes the setting for a lesbian romance. “Bathing, eating, and loving all occur against the backdrop of a desolate swampland”, writes Pearce to introduce Shadows, one of their earliest series started in 2016 to reenact a love story between two Black women in 1930s and ‘40s Louisiana. Facing the absence of documented Black queer histories, Pearce created the archive they longed to see. Portraits of the two fictitious protagonists – reenacted by the photographer and their partner at the time – appear alongside objects that could have belonged to them, such as love letters, clothes, and personal items. Staged stills from their daily lives fill the void of lost memory: long lace robes hang to dry, someone resting on a green velvet couch, and nighttime lovemaking is reflected on the blurred surface of an oak mirror.

“The way I play with illumination reflects the magical quality I feel about my subjects”

Light is a central narrative tool in Pearce’s visual realm. In one of the most striking images from Shadows, a lover stands in her nightgown, a pulsing red luminescence emanating from the bottom of her skirt. In her oneiric presence, the ghostly figure is our only clue to realising the woman’s fictional nature. As she transcends her role as a flesh-and-blood lover, she comes to embody a multifaceted archetype: she’s the ghost in the archive. “Just like a shadow”, Pearce tells me, “it’s in the room, but we’re not giving credit to its presence”. Until you have to – when it comes seeking recognition.

The pulsing red light recurring in Pearce’s work is a homage to Toni Morrison’s character Beloved from the eponymous 1987 novel; whenever she reappears, her red aura fills the rooms of 124 Bluestone Road. Weaving their project with the story of a spirit returning to her mother in Reconstruction-era Cincinnati is a testament to all the stories that might have been – for the stories to exit the realm of shadows and be acknowledged. The oeuvre-wide use of dark tonalities and scarlet illumination is not thus to be associated with tragedy; rather, it embraces the complexities of the stories of queer people of colour that inhabit Pearce’s visual world. “The way I play with illumination reflects the magical quality I feel about my subjects”, they tell me. Going back to In The Hours Between Dawn, light is manipulated to reflect the hyper-delicate balance between queer visibility and invisibility in the urban setting.

A wall-sized image of the Brooklyn skyline contributes to another of Pearce’s staged environments. This time, the backdrop is placed upside down behind a double-sized bed, the blankets are creased. On the mountain of pillows, barely recognisable in the dim light, someone is lying supine – dreaming? Pondering? Just resting? Blurred and somewhat dystopian, the city is often gazed at through a window, the barrier separating the viewer from the uninviting urban outdoors. Indoors, Pearce’s staged home environments feel cosy and warm. Here and there, symbolic references peek out: red flowers, a motorbike, a still from the 2005 documentary The Aggressives, the poster of an oily bodybuilder; role models or reminiscences of turbulent dreams. Beyond the warmth, we still sense the threat of housing instability and displacement affecting the city and its marginalised communities.

Lorde’s litany is an ever-present, echoing chant woven throughout the work: “And when the sun rises we are afraid / it might not remain / when the sun sets we are afraid / it might not rise in the morning”. Pearce photographs at night, long after the sun has set and well before it rises again; in the floating hours in between, when the house still offers a sense of safety and dreams have yet to be confronted by daylight. When it’s not dark, Pearce recreates it using a day-for-night technique, selectively exposing parts of the frame while leaving the rest in shadow, a method that recalls the camera obscura technique used by Impressionist painters. As stepping into daylight reawakens the weight of internalised fear, Pearce’s nighttime portrayals carve out a precious space of rest and healing from the community’s constant struggle for existence.