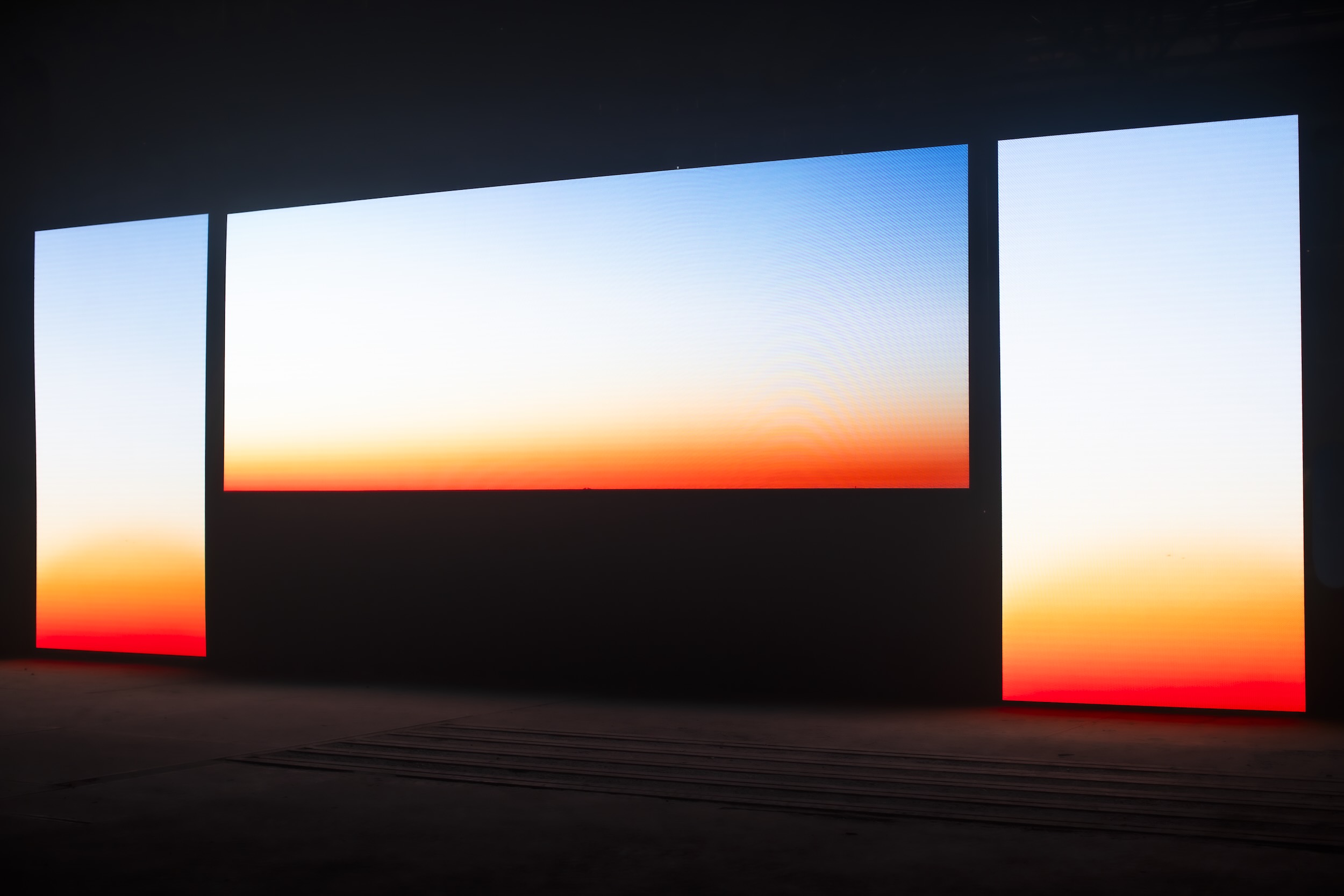

Dreamland © Mounir Raji

Contributing artists Mounir Raji, Tina Farifteh and Rosângela Rennó discuss their projects with BJP as responses to questions around home, migration, and colonialism

In a country making sense of its future following the recent election of a right-wing government, BredaPhoto Festival 2024 presents a timely and necessary conversation about identity, power, and history. The festival brings together global as well as local voices to create a chorus of photographic inquiry.

This year’s edition of the festival, themed Journeys, encourages its contributors and audience to reckon with the lasting impacts of colonial legacies. Through photographic explorations, artists take on questions about historical narratives, memory and displacement at the locus of the various diasporas present in the Netherlands.

Breda is a quiet city in the southern Netherlands, about two hours from the capital, Amsterdam. It seems an unlikely place for a photographic festival of this scale, and of this nature. The festival has been platforming both Dutch and international photographers since its inaugural 2018 edition. This year, the festival feels particularly charged. With the election of a conservative government that has taken a hardline stance on immigration and multiculturalism – the far-right Freedom Party, which won most seats in the November elections, is headed by Geert Wilders who pledged to ban the Quran and close Dutch borders – the work showcased in Breda underscores the political tensions running through Europe at large. The question now looms: what role can artists and photographers play in reframing national identity and addressing a problematic past?

“Morocco is my dreamland, and I make it look perfect, while I’m pretty aware that not everything is perfect over there” – Mounir Raji

A Romanticised Notion of Homeland

Mounir Raji’s Dreamland, shot over the last five years and culminating in a book in 2023, is a personal tribute to the Morocco of his dreams and memories. Born and raised in the Zaan region of the Netherlands to Moroccan parents, Raji spent his childhood summers in Morocco. The familiar diasporic experience of the annual pilgrimage to the homeland has shaped both his identity and artistic output. Raji, a graduate of Amsterdam FOTOfactory, has exhibited at institutions in the Netherlands including Kunstmuseum Den Haag, Unseen Amsterdam and the Rijksmuseum.

Raji captures a sun-soaked Morocco in the warm hues of the late summer atmosphere. The photographs are imbued with a sense of nostalgia, evoking his childhood memories of reunion with family, playing freely outdoors, and the boundless feelings of freedom, trust, and hope that marked those summers. “It is my own romanticised view,” Raji explains, acknowledging that the Morocco he portrays in his images is not entirely grounded in reality, but a reflection of his personal, idealised version of the country.

“I was walking in Marrakesh and I saw the title Dreamland on a big billboard for a new complex they were building,” Raji tells me. He shows me around the circular outdoor installation by beginning with an image of his grandmother, who passed away last year. “Morocco is my dreamland, and I make it look perfect, while I’m pretty aware that not everything is perfect over there.” Raji was keen to show people, particularly those with little connection to Morocco, “how amazing the colours and the people are, the freedom you have. Because we in the West are quite structured, and everything is for an agenda. Sometimes I miss the freedom we have there.”

Struck by a lack of misrepresentation about Morocco from Dutch communities around him, Raji says that in the Netherlands, many think that “Moroccan kids, they’re troublemakers”. In 2014, one of his first projects highlighted Slotermeer, “the ‘bad’ neighbourhood where they put all the migrants, like the Moroccan and Turkish migrants,” says Raji. Through stylised images, he aimed to capture the playfulness and joy Moroccan kids find on the streets, with little space to go elsewhere.

The images from Dreamland portraying the drier Moroccan climate are presented in stark contrast out here in a Dutch semi-rural location. One image taken at an Eid celebration in a large, sandy playing field shows a couple with their faces obscured, turned away from the camera, in matching blue garments. “People are afraid of Islam, [but] when they see this, they’ll probably think, ‘Oh, that looks cosy, and they’re looking beautiful’.” Raji says he ‘stole’ the shot after catching them in a mirroring stance, with a complementary flash of green from the plastic bag. It’s a relaxed, romantic scene.

Raji’s work oscillates between documentary and dreamscape, crafting images that evoke longing for a land that may never have truly existed – at least not in the form he remembers it. The project is a meditation on home and belonging, but also a commentary on how memory and nostalgia shape our perceptions of place. In a world where migration and the diaspora constantly reshape individual and collective identities, Dreamland invites viewers to consider how much of ‘home’ is built upon memory and imagination.

“When I saw the sun and the moon at the same time, I realised I am at home because I’m here. No one can tell me I don’t belong” – Tina Farifteh

The Sun, the Moon, and Borderless Visions

In Tina Farifteh’s cinematic installation piece When I Saw the Sun and the Moon at the Same Time, the focus shifts to the experience of migration and the fractured sense of identity it leaves in its wake. Iranian-Dutch artist Tina Farifteh embarks on a deeply personal exploration of belonging and identity. Born in Tehran and having moved to the Netherlands at the age of 13, Farifteh has long navigated the complex interplay between displacement and the search for home; graduating from the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, her project Kitten or Refugee? was selected for the Debut Competition and premiered at The Netherlands Film Festival (NFF) 2023.

Farifteh’s latest project, developed specifically for BredaPhoto Festival, is centred around a 24-hour journey along the Sedyk (sea dyke) in Friesland, in the north of the Netherlands, presented in a 24-minute multimedia installation. The work traces her move from Amsterdam to the village of Sexbierum, prompted by the unaffordability of urban life and a feeling of being perpetually unmoored – unable to return to Tehran yet struggling to find her place in the Netherlands. When I Saw the Sun and the Moon at the Same Time becomes a metaphor for her complex relationship with the idea of belonging in a boundaried world.

Despite the rural isolation, Farifteh’s connection to the landscape is profound. The birds, sheep and elements she encounters in Friesland become metaphors for the human desire for freedom, even as we remain confined by social constructs and borders. “Sheep are blocked by the cattle grids and fences,” she notes, “we as humans want to be free, but we keep each other framed and limited, like what we do with the sheep.”

Her encounters with nature reveal a deep connection to the world beyond the human-centric, transactional approach that modern societies often adopt. “We don’t see nature as something of value unless there’s a transactional benefit for us,” she says, underscoring how capitalist and colonial systems determine value, even in the most remote and ‘empty’ of spaces. “Who decides what has value? We say there is nothing there, but for the birds, there is a lot there.” The work is engrossing with its bright and deeply exaggerated light and shadows, set across a huge, asymmetrical three-channel screen.

Farifteh’s reflections often move between the deeply philosophical and the intensely personal. As she walks the sea dyke, listening to Iranian music, she feels the tension of belonging and rejection. “People think I’m crazy, listening to Iranian music in the north of the Netherlands,” she remarks. Yet in moments of simplicity – seeing the sun and moon together in the sky – she finds peace in the universality of the human experience: “When I saw the sun and the moon at the same time, I realised I am at home because I’m here. No one can tell me I don’t belong.”

In this project, Farifteh asks larger questions about the nature of home and identity in an era of migration and displacement. She interrogates the pressures of assimilation, particularly in conservative parts of the Netherlands where, she explains, “you have to assimilate and forget your background – it was a very violent assimilation,” she remembers of her upbringing. Farifteh also suggests a parallel with the country’s own shifting identity, noting that even these rural communities, in their resistance to change, may themselves feel like they are being forced to assimilate to a ‘new Holland’.

“For me, archives are not neutral spaces. They are sites of power. The act of collecting, classifying, and storing information has always been political” – Rosângela Rennó

Archival Activism and the Politics of Memory

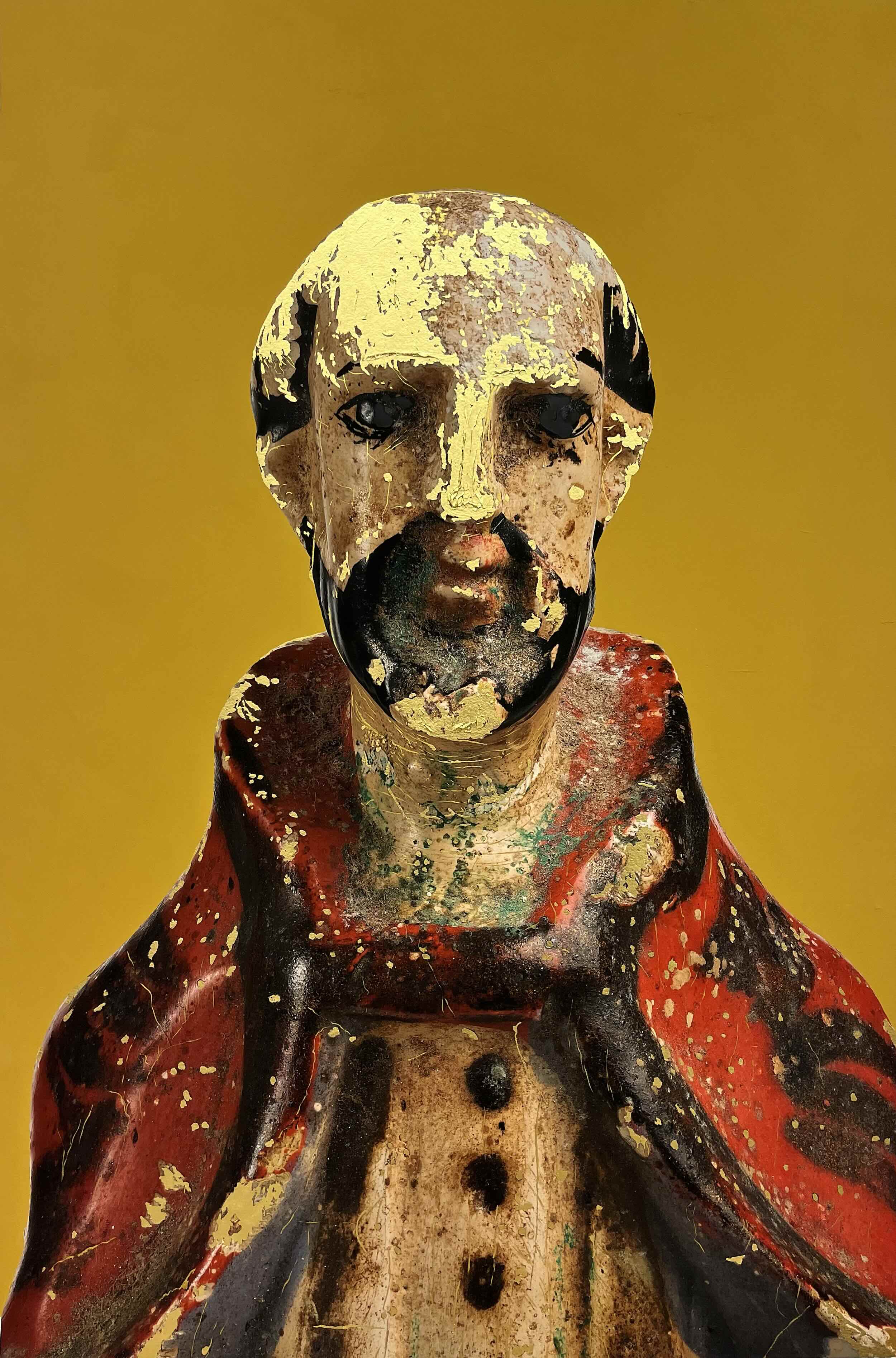

Brazilian artist Rosângela Rennó brings a distinctly archival approach to her exploration of colonial legacies. In co-production with the Grote Kerk Cathedral, Rennó presents a site-specific solo exhibition, interrogating the potential murkier history of the Grote Kerk and presents this new work in combination with existing work. Last summer, Rennó received the prestigious Women in Motion award at Les Rencontres d’Arles in France.

Through a series of multimedia installations, including photography and video, Encounters | Encontros draws attention to the little-known, interconnected history of Brazil and the Netherlands. Rennó’s work delves into historical archives to unearth forgotten or suppressed narratives, recontextualising them through contemporary interventions. Her contribution to the festival investigates how colonial powers have shaped the production and preservation of knowledge.

“For me, archives are not neutral spaces,” Rennó explains. “They are sites of power. The act of collecting, classifying, and storing information has always been political. My work aims to deconstruct that by questioning what we choose to remember and what we choose to forget.”

Encounters is a series of reappropriated colonial documents, maps and photographs that Rennó has altered or distorted. The images are faded, often difficult to decipher, as if the weight of history has worn them down. This intentional blurring forces the viewer to confront the fragility of memory and the role of colonial powers in shaping what is remembered.

“In Brazil, like many countries in Latin America, our history is still deeply tied to colonialism. The ways in which we understand ourselves and our past are shaped by these imperial forces. My work looks at how these narratives are embedded in the archives themselves. Who owns history? Who decides which voices are heard and which are erased?” says Rennó. Her use of archival materials serves as a way to make visible the systems of power that control historical narratives and challenges the viewer to think critically about how knowledge is produced and preserved, and whose interests that serves.

A Photographic Intervention

The timing of this year’s BredaPhoto Festival could not be more significant. As the Netherlands, like much of Europe, wrestles with the rise of nationalist sentiment, the festival’s focus on decolonial image-making feels like a necessary intervention. The festival’s work serves as a sobering reminder of the challenges facing Europeans from migrant backgrounds, while remaining aesthetically attuned to technical brilliance and beauty.

Taking over the city of Breda, the festival also encourages a more physical approach to, and intervention of, photography. The spaces we enter range from quaint residential streets lined with large image installations of Breda’s historic North African migrant communities, to unused industrial warehouses near the canal housing Farifteh’s film, for example. The festival’s dispersal of bikes are thus a very Dutch welcome to exploring the city.

With a sense of urgency, the festival positions itself as a site of resistance to dominant narratives. The artists at BredaPhoto Festival 2024 are blurring lines and pushing the boundaries of where photography takes its viewer.

BredaPhoto Festival 2024 opened on 13 September and runs until 03 November 2024.