All images © Emily Garthwaite, courtesy of the artist and Save the Children

The photographer was commissioned by Save the Children to tell their story a decade after the genocide

In 2014, ISIS led a brutal campaign against the Yazidi community in Iraq resulting in the recorded deaths of around 5000 and the enslavement of thousands of women and girls. This attack was recognised by the United Nations as genocide, and the horrors inflicted on the Yazidis left deep scars that continue to impact the survivors today. Ten years later, the aftereffects are still being felt deeply, as many Yazidis remain in displacement camps, unable to return to their ancestral homes due to ongoing instability and lack of resources. About 1300 Yazidi children are still missing ten years after the genocide, and over 200,000 people remain displaced, struggling with the emotional aftermath and the lack of access to basic services.

But after living in Erbil in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq for many years, British photographer Emily Garthwaite thinks that the community ought to be celebrated, and their beauty and resilience highlighted, rather than leaving the Yazidi to be “defined by the crimes committed against them”, as Garthwaite believes has often happened. “While it is crucial to highlight the atrocities they have faced, particularly the physical and sexual violence and enslavement of Yazidi women… I want to focus on those who have survived and are rebuilding their lives and showcase their rich cultural traditions and the heritage they continue to uphold,” the photographer continues.

“It’s hard to let go of stories that we feel passionate about because they’re not stories, they’re relationships.”

After Garthwaite decided to move to the town of Akre in Kurdish Iraq a few years ago, she often drove to the Zagros mountains, swam in the river, and visited the site of Lalish, the holiest site for the Yazidi community and “a vital spiritual centre for their faith [which] houses the temple of Melek Taus, the Peacock Angel”. Lalish, a place of pilgrimage and solace for Yazidis, holds deep spiritual significance as a sanctuary in which their prayers and rituals connect them to ancestors and divine beings. Garthwaite developed bonds with the community visiting from Sinjar, from IDP (internally displaced people) Camps, and from Germany, to which many of the Yazidi community fled.

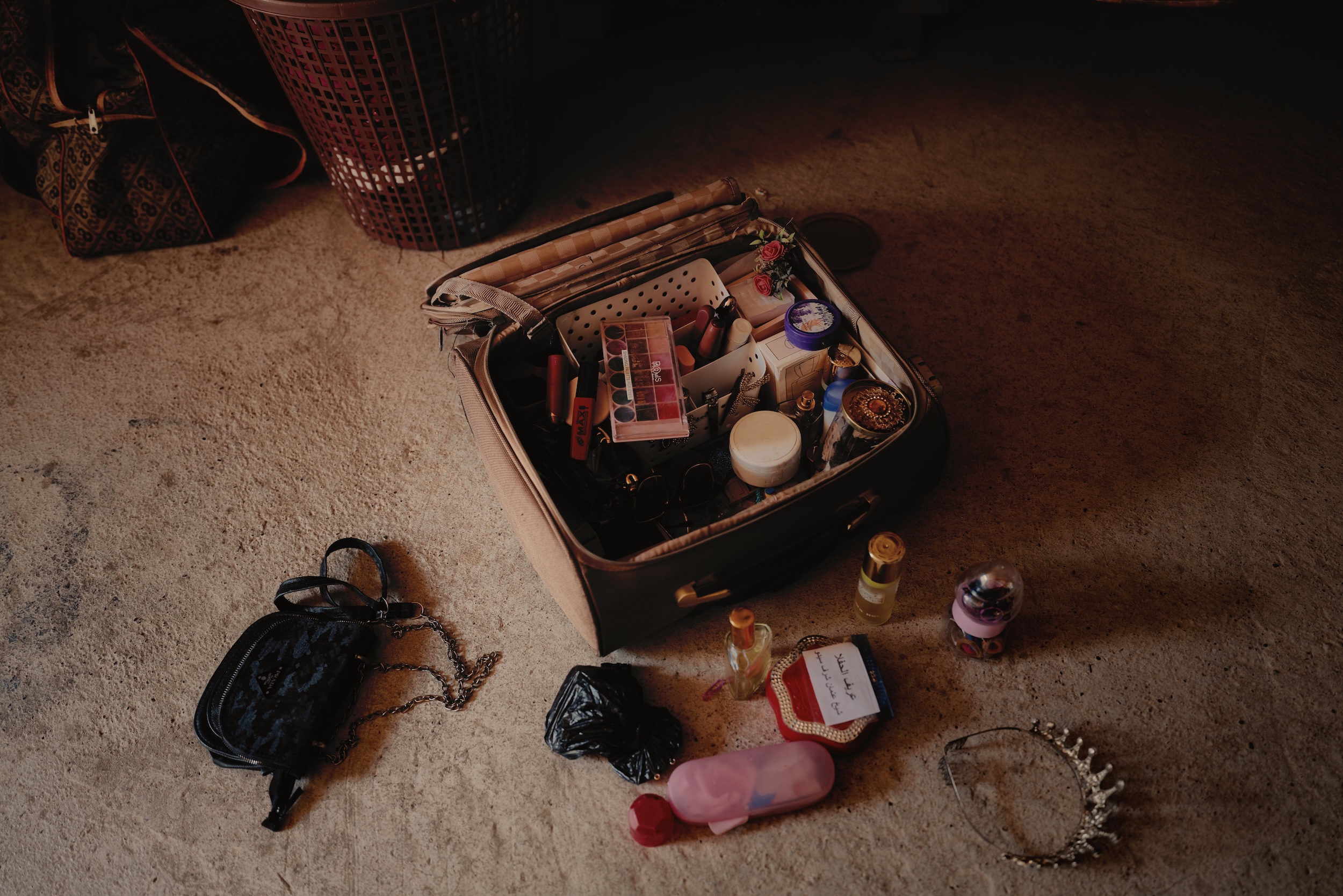

Garthwaite met a young girl, Viyan, in an IDP near Duhok on Red Wednesday, a Yazidi celebration that marks the onset of spring by collecting poppies and daisies, painting eggs, and applying shells to doorways with bread and clay. Viyan and her sister were applying makeup from old palettes under a single light bulb. “I aimed to capture Viyan as an angel, or Milyakat, in Yazidi culture – a guiding light, a beautiful blessing,” says Garthwaite of the image. “Yazidis envision angels as mermaids in the sky. She said she felt like an angel when she looked at the photo.” Tragically, half of all Yezidis killed during the genocide were children. The photographer has stayed in touch with Viyan since over Instagram, symbolising the lasting bonds and connections forged through these shared experiences.

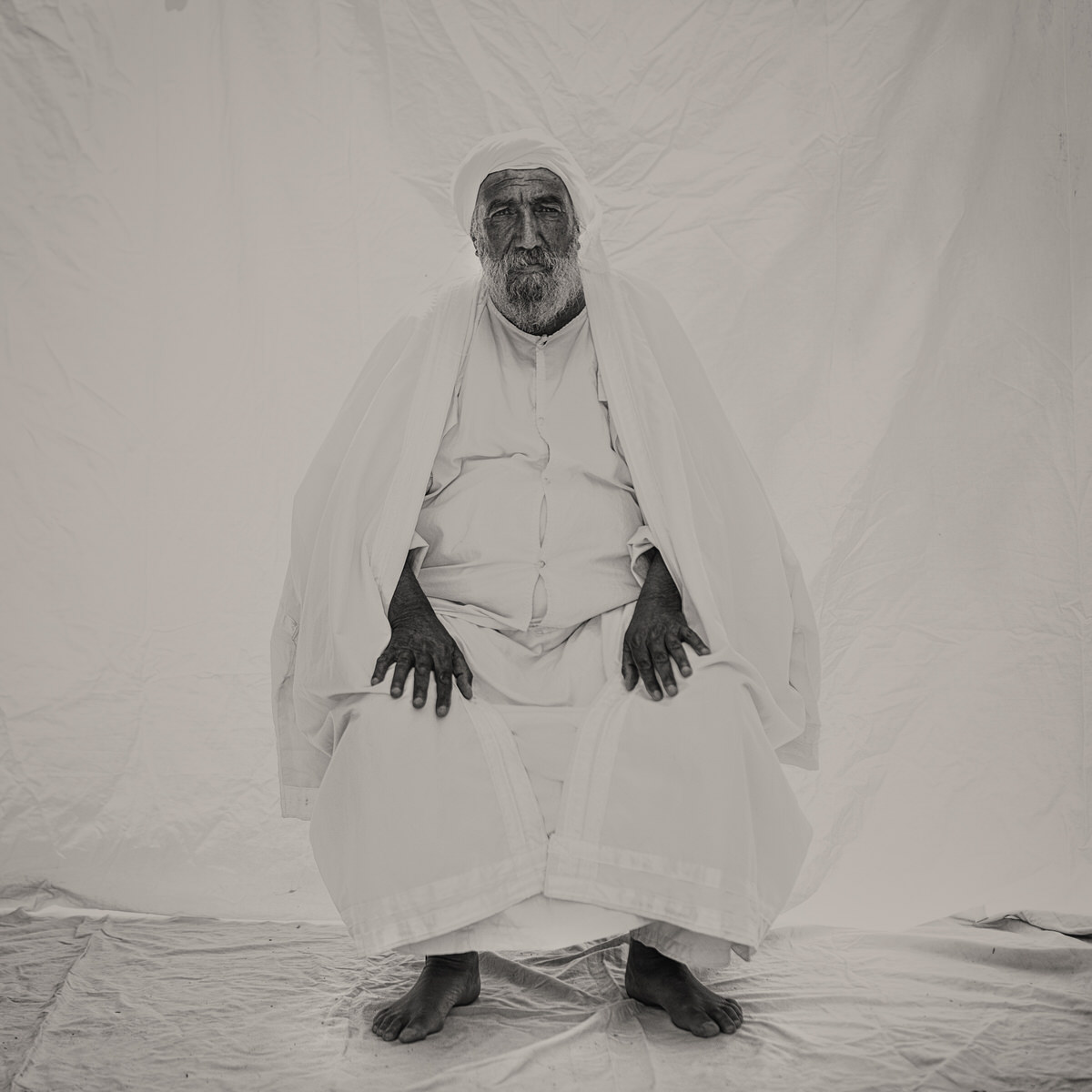

Later that year, when Save The Children reached out to Garthwaite this year to photograph families from Sinjar, marking a decade since the genocide, the photographer and charity decided to also visit the IDP camps in Duhok, in which the majority of Yazidis in Iraq reside, although many “hope to return to their homes”. Garthwaite used a bedsheet and backdrop to photograph pilgrims to the Autumn Assembly, a sacred Yazidi festival. One of the most important events in the Yazidi religious calendar, it sees members of the community from around the world gathering to participate in rituals and ceremonies that reinforce their identity and unity. She says the experience was sacred “to share in celebration with Yazidis after so much suffering in their community. I wanted to be present for that moment”.

Garthwaite will also be filming a documentary with Daniel Etter and Sangar Khaleel in Central Iraq later this year. Her second film to centre around the Tigris River in 2024, Garthwaite aims to place Iraqi protagonists at the heart of the narratives she creates, all individuals she’s met over the years “who have never left [her] mind”. And Garthwaite also wants to return to the Yazidi community. “It’s hard to let go of stories that we feel passionate about because they’re not stories, they’re relationships,” she says.