All images © Karice Mitchell

The Canadian One to Watch re-appropriates images from 1970s Black men’s magazines to skewer today’s anti-pornography sentiment

Born in Toronto in 1996, Karice Mitchell graduated with an MFA in fine arts studio art from the University of Waterloo in 2021. Studying through the pandemic had a lasting impact on her practice because, already interested in found photography but unable to access the equipment at college, she started to investigate vintage magazines. In particular, she looked at Players, which is sometimes described as the ‘Black Playboy’. Founded in the US in 1973, it featured softcore images of Black women alongside articles by, for example, Black Panthers founder Huey Newton. It was also edited by a woman for its first six issues, the poet Wanda Coleman.

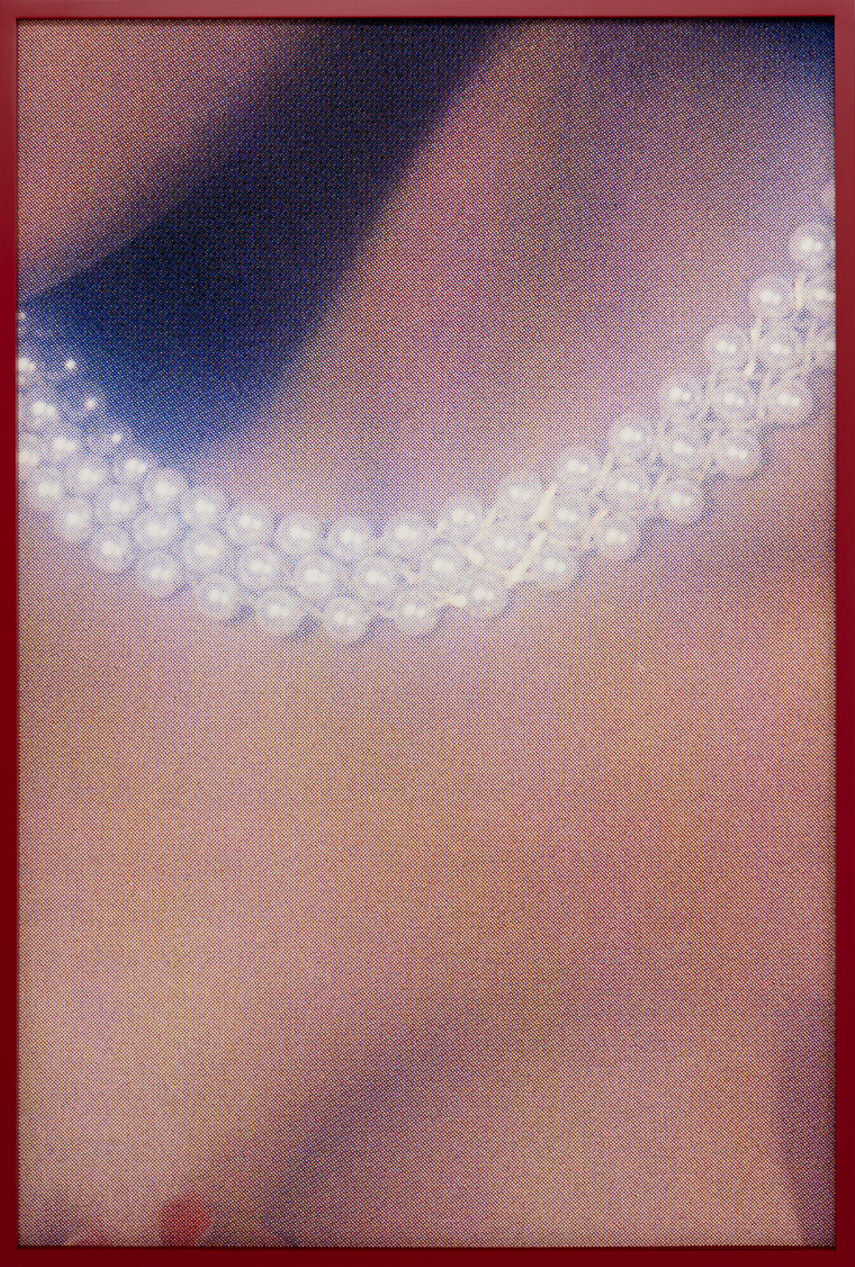

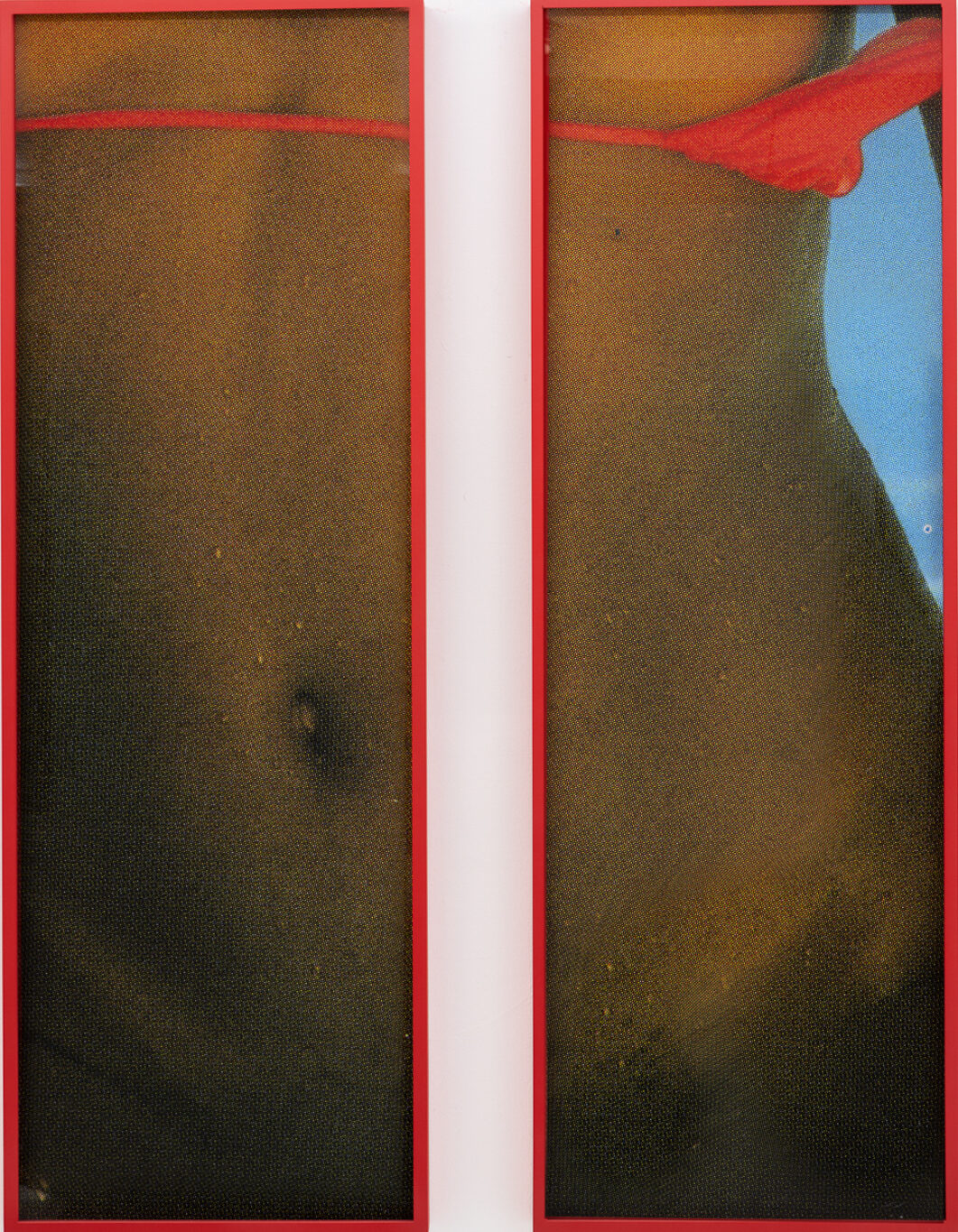

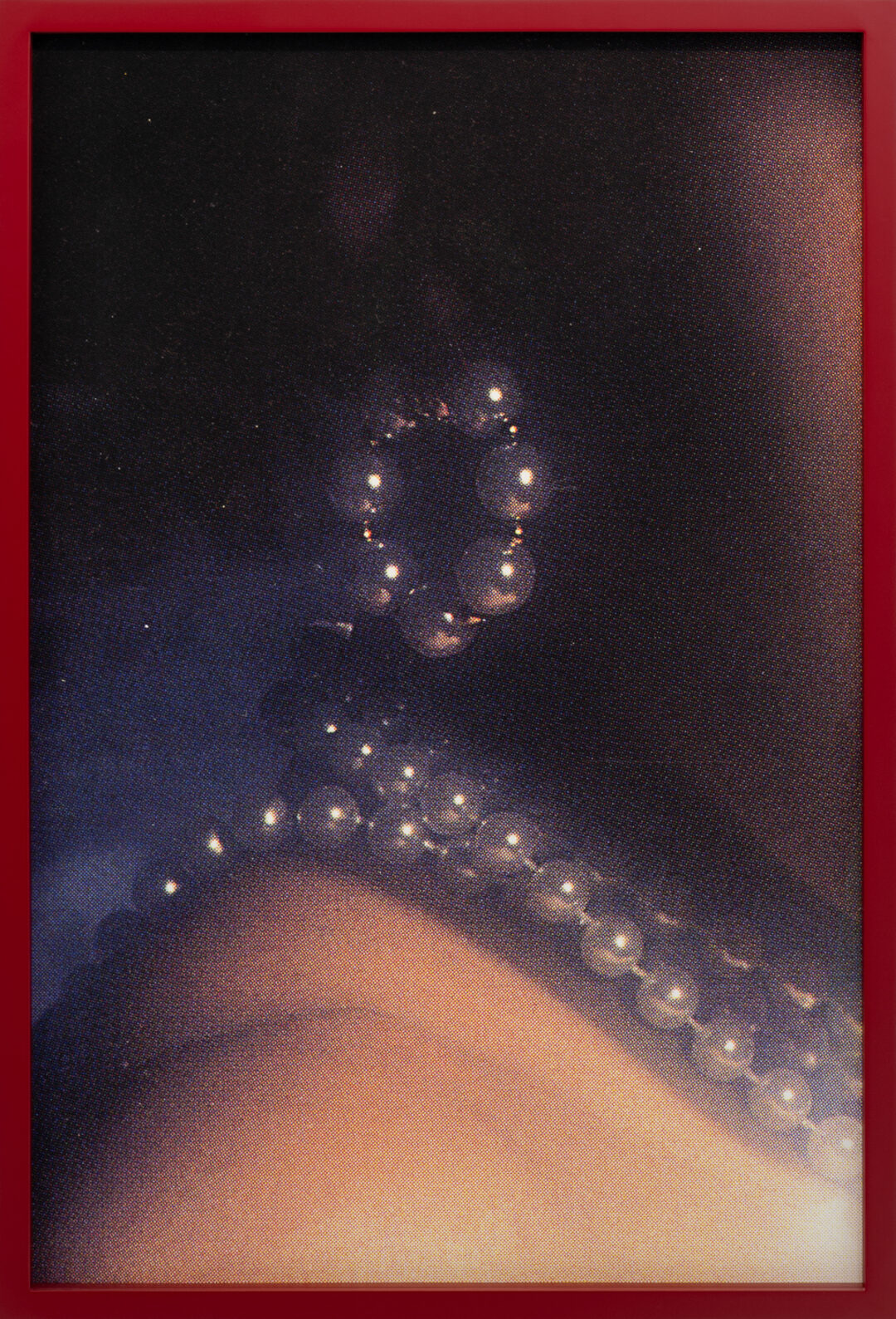

For Mitchell, this history gives Players an intriguing, potentially revolutionary edge, which she pushes further by scanning, closely cropping, collaging and digitally manipulating images taken from it. Her series Proof 28 shows tiny slivers of women’s bodies further subdivided by bra straps and thongs; Together / Apart picks out soft-focus shots of earrings and nails, “these forms of adornment, these little codes, that are so culturally Black,” she says.

“As a Black woman in an institution myself, I’m interested in what it looks like to take up space”

“I’m interested in teasing out contextually what already exists in the world, especially as it relates to visual culture around Black women,” adds Mitchell, who is a full-time lecturer at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. “Initially I had a hesitation because of anti-pornography movements, especially because anti-pornographic sentiment is often perpetuated under the guise of Black liberation. The Black female body has been subjected to exploitation under capitalism, and sexuality has often been the greatest source of our oppression.

“But for me, some of these sentiments are actually regressive when it comes to women’s agency and autonomy to make decisions for themselves. I’m interested in imagining modes where we don’t have to be burdened with colonial contexts and histories. Can we find a way to move beyond that? Can we look at this publication to see how it mobilises race in a potentially progressive way? Is there a possibility to read this image-making as subversion?”

For Mitchell the foregrounding of pleasure is also subversive, particularly because it “implicates the viewer”; recently she reshot aspects of these images as self-portraits, creating glitchy abstractions which play with illegibility and the denial of an objectifying gaze. Audience reactions to Intimacy Is have been telling. When she exhibited it in 2023 it was censored, visitors deeming it overly sexual despite the fact Mitchell was “fully consensual within that process” of photographing herself, and regarded the images as fairly reserved. “Obviously mainstream pornography is riddled with power dynamics that can be exploitative,” she muses. “But there’s an assumption that only fetishisation is happening. The historical nuance of Players starts to complicate those assumptions, and I am interested in facilitating that nuance. It’s a reclaiming and a reframing.

“I think there’s something to say about what happens when a female or the female form is in public space for the sake of itself,” she adds. “That’s what people are uncomfortable with. Images that sell things, that don’t look too different, are acceptable. It’s when the body is functioning in the public sphere for the sake of itself that there is a problem.”

This aspect stands out for Kenneth Montague, director of Wedge Curatorial Projects, founder of Wedge Collection, Toronto, and Ones to Watch nominator. In her appropriated images Mitchell has discovered a way to both reconsider and honour her subjects, he says, via a process of concealing and revealing. “She always leads with empowerment and beauty, and her subtle interventions represent a compelling new perspective, far removed from the white male gaze,” he adds.

For Mitchell, this work also resonates with her family history. Her grandparents were Jamaican but her mother and father grew up in London before moving to Canada, and seeing her mother traverse immigrant life made Mitchell question what can and cannot be said. “There were negotiations she had to make, as a mode of survival in the corporate world,” the artist explains. “Now, as a Black woman in an institution myself, I’m interested in what it looks like to take up space. I think about my mother’s experience and what’s changed for me, and I make work that is unapologetically about sexuality, subjectivity and race.”