From a new series shot in California. All images © Bandia Ribeira

Inspired by Cristina García Rodero and Alex Webb, One to Watch Bandia Ribeira takes a sociological approach to image-making

Bandia Ribeira graduated with a degree in political science, but took a photography course while studying that reoriented her towards journalism. “For a few years I didn’t know what to do professionally; in Spain, there was a lot of youth unemployment and I did a bit of everything,” she says. Signing up for a postgraduate course in photojournalism, she found her calling, starting with a personal project about a women’s prison in Barcelona.

Her first major long-term undertaking was Ni un hogar sin lumbre, ni una familia sin pan (‘Neither a Home Without a Light, Nor a Family Without Bread), which she worked on from 2017 to 2022. It was sparked by a visit to coastal Almería, south-east Spain, where she lived with her family as a teen. Realising the area had radically changed since her youth, she decided to move back to chronicle the differences. Accompanied by a journalist, she spoke with farmers and farm workers, trade union activists, economists and historians, and also visited factories, a panoramic spectrum involving the entire agricultural business. On her website, she describes the “profit- maximising food production system and the environmental and human harm it brings about”.

“I found extensive bodies of work made by women photographers such as Esther Bubley or Marjory Collins, and I was struck by how this work had not been made relevant in the history of the medium”

Evolving the project into a more personal gaze, Ribeira eventually honed in on everyday life in the region. She was most interested in the children of local migrant workers, and spent much of her time “searching for places, walking around with my camera, speaking with people I met outside, and so on”. This approach translates into an arduous production process, she adds, “because many days you come back home with no photos or many bad photos”.

But that process is also partly why artist and educator Alejandro Acín nominated Ribeira for Ones to Watch. “Bandia embraces slow photography to immerse herself in the places she works,” he says. “She is a committed practitioner, politically and artistically.” Her project Ni un hogar sin lumbre… is important, he adds, because, “It challenges the sometimes reductive and sensationalist narrative in the mainstream media about the working communities in this area. Bandia’s intimate and domestic approach to labour is unique and unusual within the long tradition of photographers exploring this topic.”

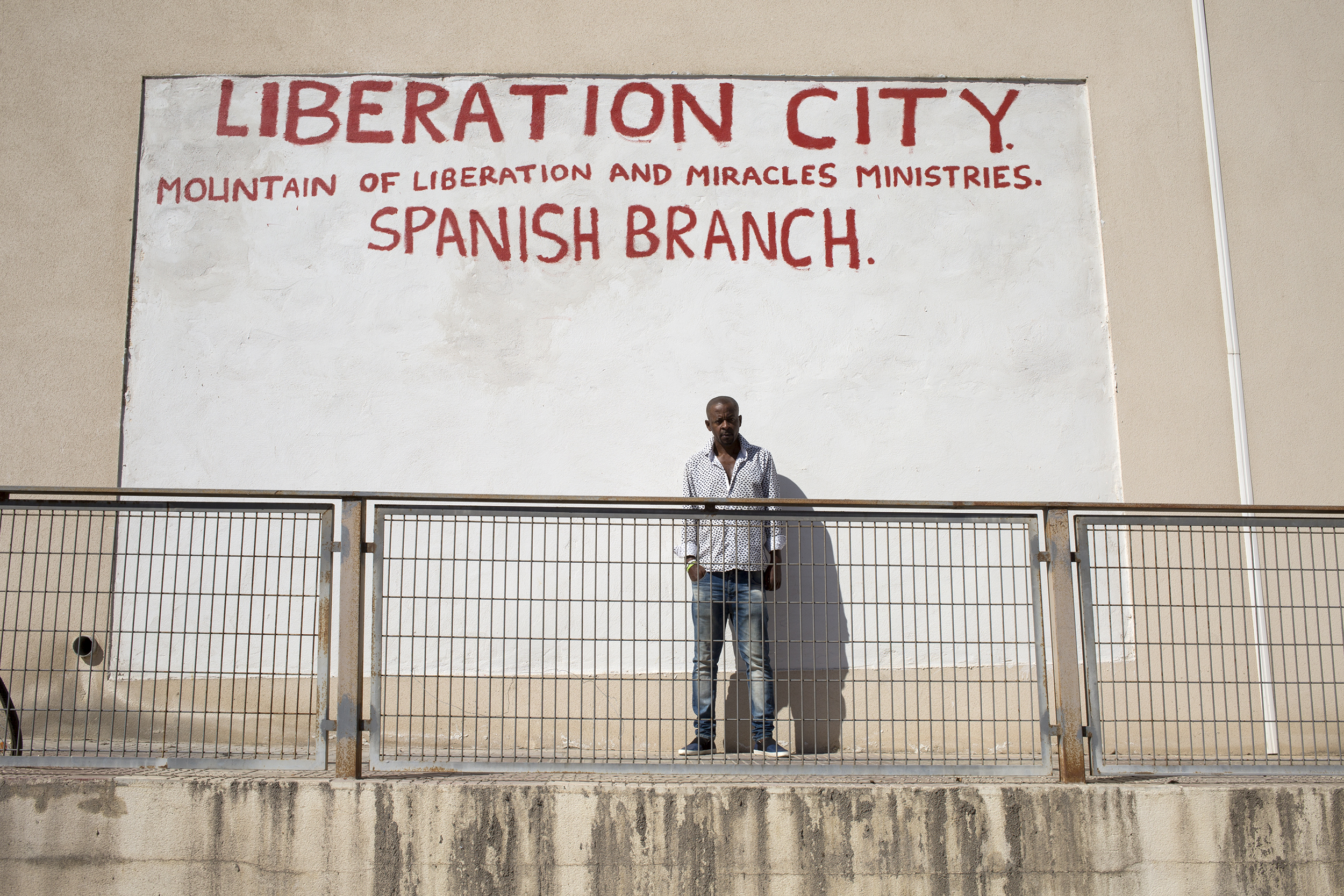

It is a tradition of which Ribeira is well aware. Her latest work was made in California’s Central Valley, where she worked for several months on a Fulbright research and artistic production grant, revisiting the locations in which Dorothea Lange photographed migrant farm workers in the 1930s and creating a modern-day update. She was also inspired by Cristina García Rodero’s colour photographs in Spain and the US throughout the 1980s and 90s, and Alex Webb’s work in New Mexico in the 2000s, both of which she found in the archive at Magnum Photos, New York.

Ribeira also made several trips to Washington, DC, to study the Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Photograph Collection, which charts US involvement in World War Two. “As many of the men went off to fight on the European front, many women took up positions in factories and other productive sectors – and so it was in the photography team of this department,” she says. “I found extensive bodies of work made by women photographers such as Esther Bubley or Marjory Collins, and I was struck by how this work had not been made relevant in the history of the medium.”

Ribeira’s Californian project marked her first time in the US, and she was unsettled by the car culture, the air pollution and the poverty she found there. She shadowed a doctor-run mobile medical unit – a caravan parked once a week near an industrial estate – which provides free healthcare to homeless people with drug addiction issues. She walked the streets talking to locals. “Some areas were real refugee camps – that made a big impact on me,” she says. “It was a kind of apocalyptic scenario – homeless people on the street and the rest of the population moving around in big cars.” It is an insight that perhaps crystallises Ribeira’s work. Choosing not to turn away from contemporary communities’ harsher realities, she makes images that are informative and encourage empathy.