All images from Desi Boys © Soham Gupta

Soham Gupta made his name capturing Kolkata’s unseen poor. Now his mood has softened, and the city’s youth movement has picked up pace

In Kolkata, young men crowd on roadsides, around food stalls, in shops, warehouses and arcades. From the tomb of Wajid Ali Shah – the last Nawab of the northern region of Awadh – in Metiabruz, to the bustle of Park Street and Mullick Bazar, men linger on motorbikes, smoke, laugh and flirt nervelessly, the same as youngsters the world over. One of them, Sahid, looks especially gleeful, his shirt removed to reveal a toned torso and a forearm tattoo sleeve (the word ‘Love’ is just visible). A woman places her ringed fingers on his bare chest, their easy smiles matching. Her eyes are relaxed, looking directly into the camera, while Sahid peers over his muscular right shoulder. His body, her face, are almost luminous against the night sky and worn paintwork of the thick railings behind them.

Sahid is an amateur bodybuilder, we learn from Soham Gupta’s Desi Boys journals. He has just started working in his father’s motorcycle garage in Tollygunge in south Kolkata, but often hangs out at the Safari Park in nearby Rabindra Sarobar – one of countless public areas or monuments named after Rabindranath Tagore in the city. “The girls are always dying to pose with me – and it always gives me a high,” Sahid says. After he has posed for Gupta, Sahid takes him to meet some of his friends nearby, boasting to them that he has just had his picture taken. “The others wanted to have their images made and I was suddenly engulfed in requests, from all sides,” Gupta writes. “And happily, I kept making images.”

These are the Desi Boys – Gupta’s friends, inspiration, subjects. They come from across this city of nearly 15 million, a swelling youth movement comprising both Muslims and Hindus belonging to a range of caste positions, including some Dalits. The idea for the project came about after Gupta was shooting a fashion editorial for New Delhi-based magazine Platform, where he was commissioned by Bharat Sikka. He began noticing what had previously blended into the background. Not just young men wearing fake designer clothing and dyeing their hair, but the way these sartorial choices constituted a new form of expression – the audacity with which they showed off, exchanged ideas, circulated pictures of each other, and saw their choices as distinctly subcultural. “There are different hints of masculinity in different places,” Gupta tells me. “They’re playing many different roles.”

Music is a key part of this new collective identity. Pune-born rapper MC Stan is an important touchpoint for these groups, Gupta says, with his lyrics describing life in – and beyond – India’s working and lower-class communities. The song Basti Ka Hasti is especially popular, its lyrics a combination of tribal hip-hop bravado and pride in a disadvantaged upbringing: “I’m a celebrity in the township!” he barks at one point. “MC Stan is very explicitly talking about the economic divide in India; he is the ultimate symbol for the Great Indian Dream,” Gupta explains. Another rapper crops up in Gupta’s journals, an amateur called MC Cidnapper. “He was not older than 20 – with a lock of golden hair up to his shoulder,” Gupta writes. The boy bounds over to him, excited that he might have his photograph taken and reciting a few lines from a new song about a girl who left him for a richer man.

New India

Desi Boys depicts a globalised India, but not in the way one might associate with tech-hubs, Silicon Valley CEOs and the country’s recent lunar landing, which prime minister Narendra Modi described as “mirror[ing] the aspirations and capabilities of 1.4 billion Indians”. Instead, the globalisation the Desi Boys experience relates mostly to liberalisation, social connectivity and employment – all of which have come about via mass mobile phone uptake in the past decade. In supremely competitive higher education and job markets, the arrival of the gig economy has offered new routes out of unemployment. The criss-crossing journeys these jobs involve add to Desi Boys’ sense of motion – of restlessness in a hyperactive city, of youthful excitement matched by its surroundings. “For many bourgeois and upper-class families, these boys are looked upon as a menace,” Gupta says. That, more than anything else, surely boosts their subcultural credentials.

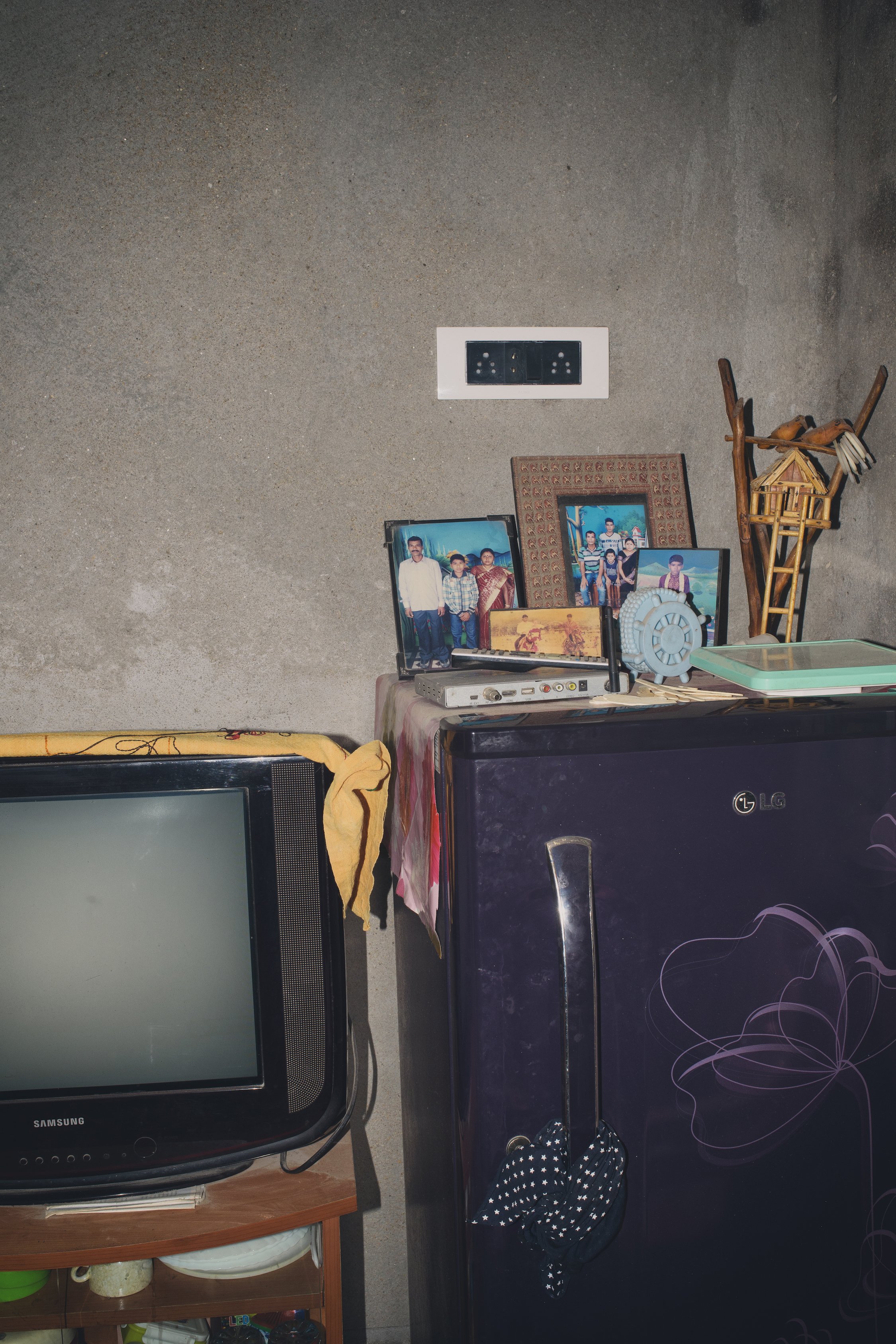

Desi Boys was made in a specific Indian – and Kolkatan – context. Despite the fake Gucci clothes and Levi’s T-shirts, it is a simplification to assume that globalisation means simply emulating the west. There are other motifs alongside the preference for South Asian hip-hop. Several of Gupta’s encounters happen while searching for the next bowl of steaming biryani, while buildings’ pastel walls, DIY advertising boards and the boys’ sandals and coiffed hairstyles are distinctly Indian. The flash illuminates sections of the graffitied walls behind each of Gupta’s subjects. Exposed pipes and security grills speak to the thousands of vendors who line Kolkata’s daily markets. The youngsters smoke and flex their muscles, gestures whose universality as expressions of young masculinity give them an endearing edge. It is clear that there is a deep affection between artist and subject. “We are like brothers,” Gupta reflects.

The role of religion

But more than any visual cues, it is India’s tense political and religious climate that gives Desi Boys its texture. Led by Modi since 2014, the country’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has proposed a series of legislation which disadvantages India’s Muslim population. Passed in 2019, the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) excluded Muslims from a fast-track for persecuted minorities to attain citizenship, while an accompanying amendment to the National Register of Citizens (NRC) similarly planned to exclude Muslims from an accelerated naturalisation process. Following widespread protests in early 2020, the NRC has yet to be implemented nationwide, with West Bengal among several states not under BJP control saying it will not enact the rulings. Cities with historically Muslim names have been renamed to reflect the BJP’s Hindutva ideology – Allahabad has become Prayagraj; Osmanabad is now officially Dharashiv, for example – and mob intimidation and violence against Muslims has become increasingly normalised.

The Desi Boys belong to both religions, and Kolkata’s political history plays an important part in the social harmony of the project. West Bengal was led by the communist Left Front from 1977 until 2011. “There’s no room for xenophobia in West Bengal – we grew up among too many hammers and sickles,” Gupta says. He recalls a discussion with a young man after he commented on his celebratory dress: “Eid is for the Muslims, but at the same time Eid is for everyone.” Gupta connects this environment to the willingness of the Desi Boys to express themselves, especially with styles that subvert a traditionally conservative culture. “Here, people feel safe to assert themselves, to go out in clothes that they like, to dye their hair. Desi Boys is a response against the xenophobic phase we’re going through,” he says.

Gupta describes Desi Boys’ subjects as “all subaltern in some way”. He draws a link with his 2017 project Angst, in which he made pictures of those at the foot of Kolkata’s social and caste ladders – the homeless and the hopeless. The word ‘subaltern’ resonates deeply in Kolkata, particularly in its adoption by late-20th-century postcolonial theory. Ranajit Guha, Partha Chatterjee and Gayatri Spivak, founding members of the Subaltern Studies group, all attended Kolkata’s Presidency College (the latter two were also born in the city) before developing their ideas abroad. The group applied Antonio Gramsci’s idea of the subaltern to the marginalised populations whose experiences had been omitted from the history of India, especially narratives of how anti-imperial thought had developed into the independence movement. The subaltern is not simply someone who is poor, neglected or part of a system-based underclass. It means that they are excluded from the economic, social and cultural institutions of power within their colonial society, and – as Spivak queries – may also lack the means to articulate their condition if the language and norms of the coloniser have been impressed upon them.

“Desi Boys is a response against the xenophobic phase we’re going through”

Subaltern experiences

How does the subaltern relate to Gupta’s subjects – and his wider project? On the one hand, his photographs are the voice of subaltern experience. The way Gupta makes pictures is collaborative, but not prescriptive. The boys ask for their portraits for their WhatsApp pictures: “Come, take a group photo – of all of us! And you better send them to us! Not just one or two, but the entire set!” they tell him. His portraits perhaps circulate among his subjects more than they do in a western context, in which exploitative power dynamics risk being repeated. The image is networked, not static.

But still there is wariness around the ethics of display, particularly with Angst – the portraits at times shocking, raw and near-theatrical in their depiction of alterity and deprivation. The series was included in the 2019 Venice Biennale, the epitome of western art-world polish. But, as shown by the displacement of street vendors before the recent G20 Summit in New Delhi, the Indian establishment often chooses to look away from its own working classes. In this context, looking at people is recognising that they exist, even if it risks showing them as object not subject. To share images today is to engage with a specific moment in Indian history, to show integration, joy and modernity when openness seems on the wane. It is history without the responsibility of history; a record without the dryness of documentary.

When Gupta first titled Desi Boys, he was cautioned by critics whose advice he paraphrases in the Desi Boys journals. “How can you name it Desi Boys! You’re further marginalising the subaltern by calling this work that!” But Gupta’s photographs can be seen as a subaltern source – as history from below, with photography a new discourse. “Angst was made at a time when I was really emotionally down. It had all my anger in the work for a world that doesn’t care for people who are marginalised,” Gupta says. Desi Boys reflects a mood shift, but a way to invite his subjects into the image-making contract. “I’m more balanced now and it shows in the pictures,” Gupta continues. “They’re a celebration of life – my version of the truth that I am trying to portray.”