Bern Schwartz, David Hockney, contact sheet, 1977. Gift of The Bern Schwartz Family Foundation, 2021 © The Bern Schwartz Family Foundation

Richard Ovenden has spearheaded a photo focus at Oxford’s Bodleian Libraries, helping ensuring archives find secure homes and rediscovering historic images

“A generation of photographers is starting to retire or die, and their archives are now coming to a point where they need to find a home,” says Richard Ovenden. “There will be a bit of a Darwinian process for some. Other work will end up in the commercial trade, sold as groups of prints. What scares me is the archival record – shoeboxes full of show catalogues, or the posters rolled up with elastic bands around them, or the piles of their work that ended up in magazines, be it Creative Camera or Harper’s Bazaar.

“Few photographers think of their archive and think of their life,” he continues. “They tend to think of their archives as their stock of photographs and the negatives, because that’s how they draw their income. The other stuff is just clutter. But photographers actually live lives. Sometimes the photography dominates their whole being, sometimes it’s a small part, but they still have families and other interests. That’s where an archive or a library like ours comes into its own, because we’re interested in everything – what motivated them, what were the challenges of their particular time, what else was going on, what were their political interests?”

“We’re interested in everything – what motivated the photographer, what were the challenges of their particular time, what else was going on, what were their political interests?”

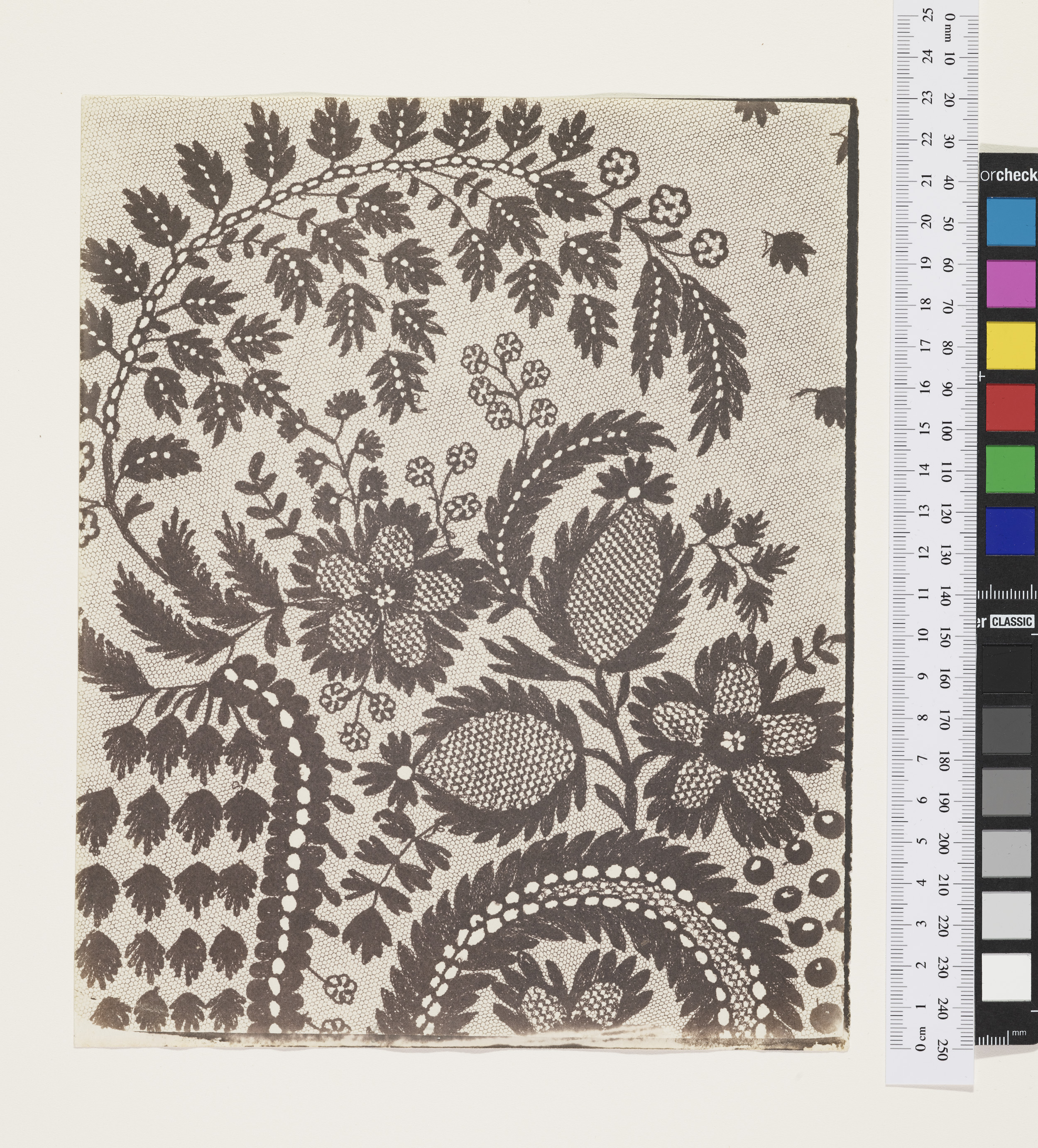

Ovenden is Bodley’s Librarian, the head of the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Libraries, which date back over 400 years. After a 20-year stint with the institution, Ovenden was appointed its lead in 2014, and has spearheaded a new interest in photography. Shortly after he was appointed, the libraries acquired the William Henry Fox Talbot archive, which encouraged others to donate or deposit Talbot-related work. In the last decade, the Bodleian has also acquired archives by photographers including Daniel Meadows and Bern Schwartz. In 2014, Martin Parr was commissioned to make new documentary work in Oxford, while in 2022, Garry Fabian Miller was the first fine art photographer to be awarded an honorary fellowship by the library.

The final instalment of Miller’s lectures at Oxford took place at the end of 2023. He has also published a book, Dark Room, with Bodleian Library Publishing, and showed his work in an exhibition at the institution, Bright Sparks: Photography and the Talbot Archive, which paired contemporary artists with the photography pioneer. The show was curated by Geoffrey Batchen, an Oxford history of art professor and photo specialist. He also drew on the Bodleian’s collections to create another show, A New Power: Photography in Britain 1800–1850, which ran at Oxford’s Weston Library earlier this year.

Even though the Bodleian is now actively pursuing photographic artists and their works, both have been part of the libraries since the medium was invented, Ovenden explains. The Bodleian is a legal deposit library, meaning it is entitled to receive a copy of every book published in the UK and Ireland. This includes photobooks, so the centre holds an edition of Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature – the first commercially published book to include photographs. It also has copies of classic publications and supplements like The Sunday Times Magazine. Older gems in the collection include The Illustrated London News, one of the first periodicals to reproduce photography.

Many of the Bodleian’s regular books include photographs too – what Ovenden calls a huge “latent” collection yet to be mapped out. The archives of UK institutions including the Conservative Party and Oxfam are here, and they include many photographs. There is so much, in fact, that in 2022 Ovenden secured endowed funds to appoint a first curator of photography, Phillip Roberts, who was charged with collating what the libraries hold. Case studies are vast in number and Ovenden estimates there are over a million photographs. “We have an album of 120 Julia Margaret Cameron prints because we have the archive of Henry Taylor, who was one of her close friends, so she gave this album to him,” he recalls. “Another example is the archive of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel – all these Victorian clergymen out in the world had cameras, and when they came home they put lanterns and slideshows together and showed them to raise money.”

The essential challenge of Ovenden’s post is how to organise the photography collections in a meaningful way within the library’s wider project. “My problem was how we could make this more purposeful, to become a more distinct and visible part of our collecting,” he says. “And how we could develop a strategy to identify areas where we could do things that other institutions couldn’t.” The fact that the Bodleian is a library makes a difference. Unlike institutions such as the V&A or Tate, the Bodleian is not just interested in prints; it is concerned with the entirety of an archive; the details which might seem peripheral but which flesh out the circumstances in which photographs are made. This includes notebooks, finished ads and business records for commercial photographers, or casts, seed packets and political records within the Talbot archive.

“We want everything that documents the life of an individual and their work,” Ovenden explains. “This is necessary because we’re a universal library. There are people using our library for purposes we don’t even know – academics from scientists and medics to social scientists and those in the humanities, but also people from outside. One user was the set designer for Doctor Who, who came in with all sorts of weird and wacky requests.”

“Dealing with an archive is expensive for an institution, whether it’s a library, archive, or museum. You have to commit to that cataloguing and conservation work, but also exhibitions, publications and seminars, and all those things require resources”

Being the Bodleian has other advantages too. Renowned the world over, it is able to attract donations such as the “transformational” £2million gift from The Bern Schwartz Family Foundation, which funded Roberts’ position. At a time when other institutions are struggling, the Bodleian is an attractive institution to place work. Daniel Meadows’ archive was originally held by the Library of Birmingham, which put together a world-class photography collection before running short of funds. Meadows’ archive was mothballed, alongside other photographers’ collections, until the Bodleian Libraries stepped in to ensure Meadows’ back catalogue remained open to the public. This cautionary tale is one of the reasons Ovenden was keen to permanently endow the curator’s position. “To take Meadows as an example, I didn’t want to say yes until we’d got the money to catalogue the archive properly, so that it wouldn’t just end up as boxes in a basement,” Ovenden says.

Ovenden points out the Bodleian is not the only library to do this kind of thing – University of St Andrews Library holds work by Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert, while the National Library of Wales acquired the Philip Jones Griffiths archive in 2011. Institutions prioritise archives which make sense for them, so it was logical for the National Library of Wales to collect the work of Jones Griffiths’, who was famous for his projects in Vietnam but was a Welsh native. Meanwhile, the Bodleian holds a smaller archive of work by Dafydd Jones because it was made at Oxford student social events from 1980–1991.

Institutions liaise to make sure they do not collect the same items, Ovenden says, but there could be more collaboration and joint purchases, as happens in other media. (He helped organise a joint acquisition of the Franz Kafka archive in Germany). Photography is also collected in a fairly dispersed manner across the UK’s public institutions, with no overarching strategy to co-ordinate what is essentially a national collection, albeit one spread across various homes. “Some national strategic thinking could play a role in making sure that gaps are not created,” he says. “Dealing with an archive is expensive for an institution, whether it’s a library, archive, or museum. You have to commit to that cataloguing and conservation work, but also exhibitions, publications and seminars, and all those things require resources. While there’s a degree to which institutions can prioritise, I think it’s better to grow the cake rather than to argue about how slices are divided up. As this generation of photographers starts to move their work out of their homes, the public funding bodies need to come together.”

This institutional support for photography is a “no-brainer” for Ovenden because photography is so important – a key medium of communication ever since its invention, in prints and art institutions but also in books, magazines, pamphlets, ads, posters and more. He includes digital communication in this remit, with the Bodleian now collecting digital files and even archiving UK webpages. Ovenden has established a legacy that will continue at the Bodleian – and hopefully beyond – long after his time at the libraries, to ensure that his efforts are not just a personal passion that ends with him.

Even so, it is a personal passion. Ovenden’s sister was a professional black- and-white printer and showed him around the darkroom; as a young man, he tried for a place at the Polytechnic of Central London and was interviewed by the formidable Victor Burgin. “That wasn’t easy, so I ended up going off to university instead,” he laughs. “But I was the photographer on the student newspaper for a while and just always kept up the enthusiasm. I went to the Royal Academy’s Art of Photography exhibition in 1989 and realised the sheer depth of the history, and carved out a role as a curator of photography from there.” It is a profession that has served him well, but more importantly offered a legacy that benefits the entire nation.