© Jesse Glazzard. All images courtesy the artists

Trans and Queer artists are using photography as a means to build community – both in images and in practice

On the cover of Myriam Boulos’ What’s Ours, a photobook about power, protest and queerness the artist has been making since the 2019 revolution in Lebanon, a lesbian couple are kissing. Both women have their eyes closed, lips locked, and hold each other tightly as the artist’s flash illuminates the landscape of their faces. Boulos spent a lot of time on the streets in Beirut during the revolution – a protest against the government’s ongoing corruption and austerity measures, further complicated by the Covid-19 pandemic and the catastrophic port explosion in the city’s harbour – and this experience continues to redefine her life and practice.

The image of the couple kissing, the most culturally mobile of the artist’s entire portfolio, epitomises how Boulos sees the world: raw, real and up close. She describes the impetus behind the book as “looking for tenderness in a city of destruction”, and its central tenet is that intimacy is political. Through her visceral photographs, Boulos reckons with how the body assimilates pain and trauma, and how desire, often our only escape in times of crisis, is entrenched in our political and social realities.

“My friends and I used to take pictures naked in the streets of Beirut,” Boulos explains. “It was our way of reclaiming our streets and our bodies. Everything that is supposed to be ours.” Portraiture for the artist has always been a way to metabolise the present moment, especially when the issues at hand feel insurmountable. She and her collaborators use the medium to imagine an alternative reality, a space in which they can temporarily feel free. “Photography is about creating a space to exist,” says Boulos. “For me, images are a physical space; existing through images is existing physically.”

“Not complying with the rules of a heteronormative world is a deeply emotional, sometimes shattering and isolating experience” – Bérangère Fromont

The politics of visibility have long been the purview of portraiture for members of the LGBTQIA+ community, who have used the medium to provide evidence of their love and lives since its inception. As a visual strategy, photography has been a tool for radical coalition and solidarity, building and nurturing self-regard and togetherness. While portraiture as a mechanism may seem deceptively simple to a cis-heteronormative audience, existing through images is not just a survival strategy for Queer people. It is proof of existence in a world in which law and institutions continue to deny our fundamental human rights.

As Boulos’ work reminds us, portraiture has been central to the ideology of resistance. Yet, the tension between visibility and safety is increasingly complex, especially in the context of social media, where identities and personal information can be easily accessed. “Since the revolution, I’m very conscious that images can put us in danger,” she explains. “It’s not the right time to bring the book to Lebanon. In the last month, politically charged, anti-LGBTQIA+ campaigns have drastically reasserted that homosexuality is against the law and the consequence is the death penalty. We’ve also seen increased attacks by radical groups as intimidation tactics. It’s too risky for me and my collaborators to be seen now.”

The personal is political

Boulos is not alone in her safety concerns. The UK prime minister regularly promotes preaching anti-trans rhetoric and health bans in the United States are fundamentally altering the material reality of transgender people. This summer, Italy removed the parenting rights of non-biological lesbian mothers, and Hungary instigated a law encouraging citizens to report same-sex families for violating the constitution; meanwhile, parts of Poland still uphold LGBT-free zones.

Despite the many hard-fought freedoms won over the last 100 years, the rise of the far right foreshadows a future in which the LGBTQIA+ community is increasingly marginalised in violent and insidious ways, rendering hyper-vigilance the only way of life. Where do we stand now? How are the politics of representation shifting? How does portraiture function as a care modality? And perhaps most pertinently, what does it mean to make work in an era in which visibility is both liberating and dangerous?

While the representation of the LGBTQIA+ community in culture is evolving, Queer image-makers are rarely recognised for their contribution, and most mainstream storytelling is still told from an outside perspective. “We are fetishised, objectified and routinely targeted by hate speech. How can we possibly build a sense of self in such conditions?” says French artist Bérangère Fromont, who uses her work to reclaim space and fill representational gaps. “I’m fond of the idea that Queers anywhere are responsible for Queers everywhere.”

In L’amour seul brisera nos cœurs, Fromont’s recent book, the artist celebrates dyke identities, creating an “archive of our memories, our imaginations and our dreams for the future”. The project, published by À La Maison Printing, presents a monochromatic patchwork of lesbian love through a playful exchange between Fromont’s images and poetic texts by Elodie Petit. Focusing on the representation of lesbians at the intersection of several forms of discrimination, the duo use gesture and proximity in their fight against Queer women’s erasure in wider culture.

“Not complying with the rules of a heteronormative world is a deeply emotional, sometimes shattering and isolating experience,” explains Fromont, who considers photography a space in which marginalised groups can share knowledge and build a survival network. “Staying in the shadows doesn’t have to be an obligation. I wanted lesbian love stories to be shown and enacted by people who experience it, for whom it is a physical reality.”

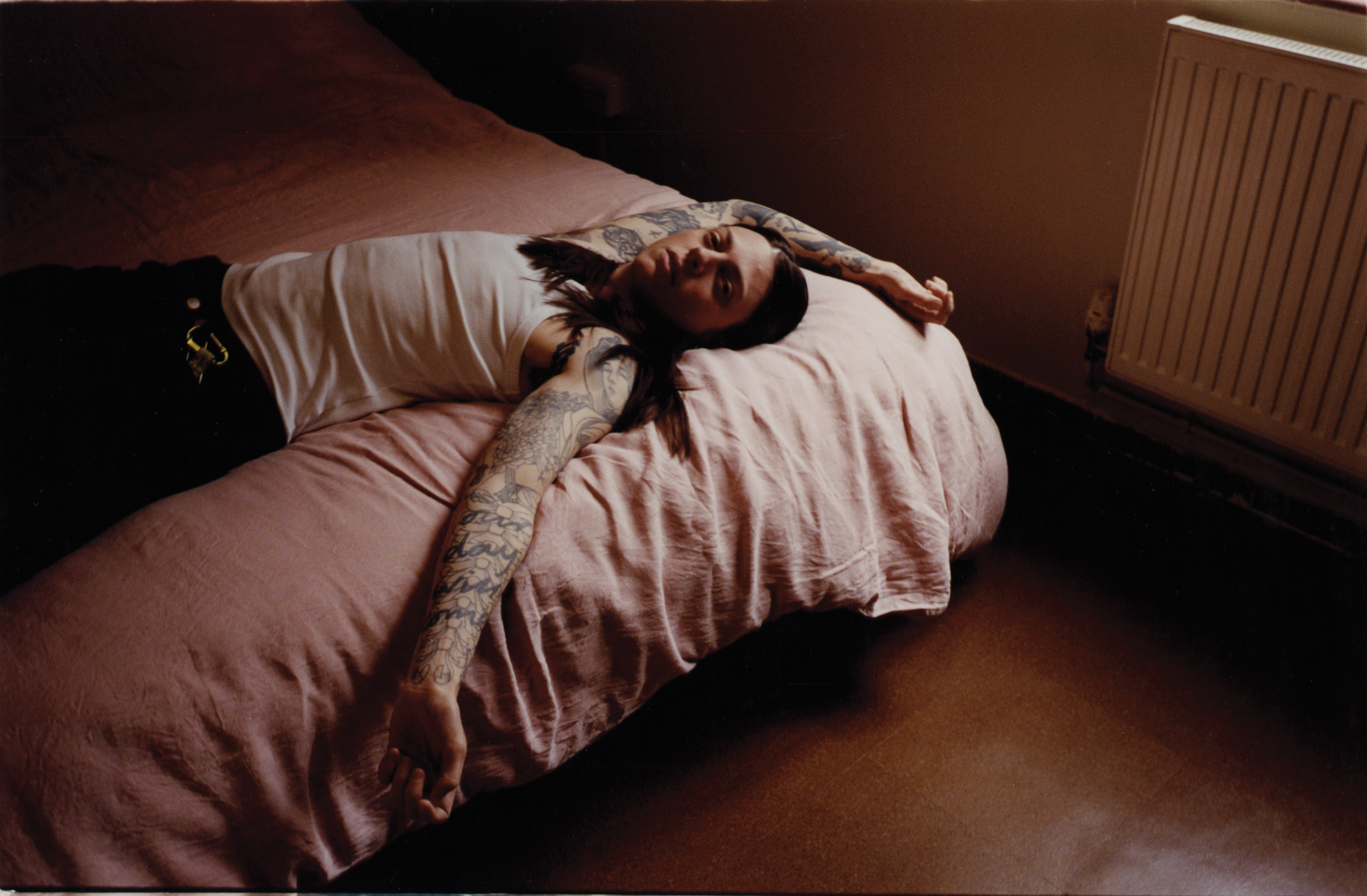

For the last four years, Jesse Glazzard has been documenting his transition in Testo Diary, a deeply personal exploration of his life after top surgery. Through the images, we witness Glazzard finding himself anew, with the loving support of his then-partner, Nora. The project was initially born out of boredom, during the London-based artist’s six-week recovery post-surgery. But over time it became more mission-led, an opportunity to address the lack of trans portraiture in the UK.

“We are living in a weird time,” says Glazzard. “We can exist freely but equally face so much backlash. On the one hand, the community is bigger now. It’s been powerful to witness the changes in my friends over the years as they are transitioning. But with greater visibility comes risk and hostility.” For many individuals, the journey to gender euphoria is not linear, and is deeply affected by sociopolitical contexts. “Some friends take testosterone, then they will go off it briefly. Even for me, sometimes I think I should go back because it’s so scary right now. This experience is just one of the reasons why we need to tell our own stories.”

Self-portraiture is just one facet of Glazzard’s practice. In Camp Trans, he collaborates with a community festival that exclusively hosts trans, non-binary and gender non-conforming people in a safe space, encouraging joy and rest from the binary pressures of everyday life. In his latest work, Soft Lad, he reclaims the northern slur in a series of luscious portraits of transmasc individuals resting and relaxing at home and in nature.

“I’m only documenting the private spaces of people I’m close with, and most of the time, the work doesn’t become public. And if it does, it’s consensual,” says Glazzard of the delicate ethos of his practice. “I’m not sure I will ever be able to show the Camp Trans work, but it felt important to make it.” For Glazzard and others, building the archive and centring care in a practice is more important than showcasing the work, though it is work that also explodes our understanding of the linear, contained and sequential conventions of the cultural production of photography.

“As Queer people, we can’t wait for laws to change; for someone to tell us we can do certain things. We have to take chances, embrace our desires and express ourselves” – Janina Sabaliauskaitė

Create safe spaces

Contemplating modes of display and circulation which best serve the community is also integral to Devyn Galindo’s practice. A non-binary Mexihkah transdisciplinary artist based in Los Angeles, they opted to launch their first book in a space in which those who had participated would feel most comfortable. “I feel like I’ve been very centred on ‘by us, for us’ from the jump,” says Galindo. “I try to keep it more for the community, even to the detriment of my work being seen more broadly.”

While these values hold true for the artist, the rising violence across the US is also something they have experienced first-hand, and that has motivated a change in approach. “Right now, the work needs to reach beyond our community because we’re living in such an isolated echo chamber; the ramifications of that charted with the rise of hate crimes. I’m optimistic that if the work has a wider reach, it could create more safety and understanding about our community, instead of divisiveness.”

In God in Drag, a project Galindo has been working on since 2017, they explore their gender journey alongside their transmasc siblings in a multifaceted, intimate series made across the US. Like Glazzard, Galindo’s collaborators embody trans joy and speak to a new era of body positivity in which masculine femininity and feminine masculinity are not just seen but celebrated. In particular, God in Drag speaks to the sweet and tender friendships accompanying the tougher masculine aspects of taking testosterone, creating a remarkable contemporary portrait.

Galindo sporadically appeared in their previous bodies of work, but in God in Drag they centred themself as much as their collaborators, reconfiguring the power dynamics of the work. “I’ve hidden behind the camera for so long,” says Galindo. “The only way to push through this heightened fear is to create work where I can [also] see myself through the lens of my community.”

Being vulnerable in front of the camera is just one of the evolving aspects of creative practice for artists such as Galindo. The lateral experience of kin-building is also central, and goes beyond film and photography production to engage with all kinds of community work, from art collaborations to a monthly dance party. “I’ve been trying to think of all of my life as part of my art practice these days,” they explain. “The fear just motivates me to go even harder.”

Building community

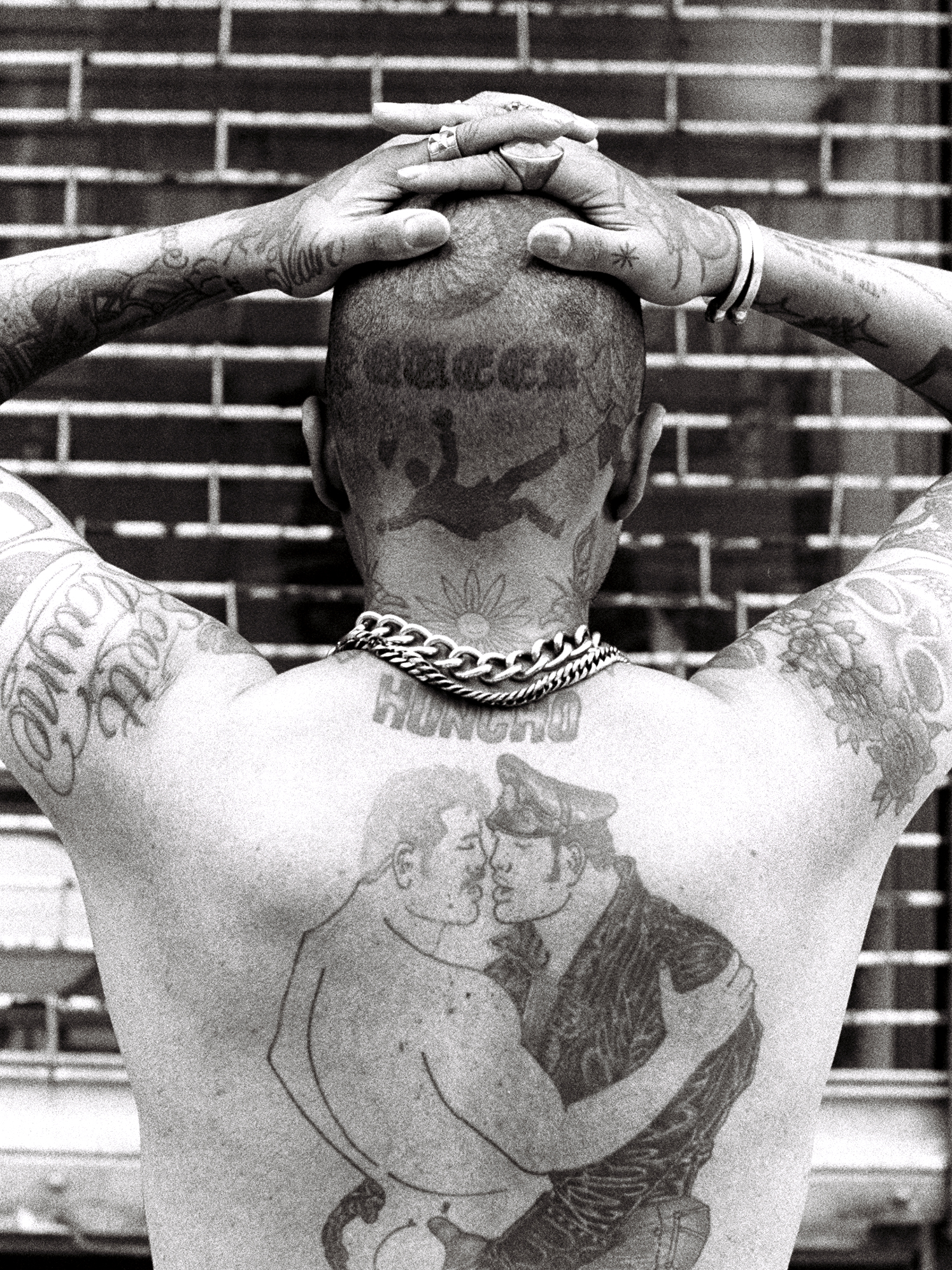

For Queer artists, manifesting care goes beyond the politics of representation or their photographs alone. It is an intrinsic part of the work. Janina Sabaliauskaitė is an image-maker but also an educator and archivist, who curates festivals and runs a black-and-white darkroom in Newcastle for the Queer community. In her hands, photography is a tool for organising, as well as an act of resistance, reflecting her desire to build safe environments for creativity and play.

“Amazing things can happen when you empower somebody to use a camera or develop film and print pictures,” the Lithuanian artist says. “The most important thing is that people have the tools to start archiving their own lives.”

In Sending Love, an exhibition of Sabaliauskaitė’s work at Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art, Sunderland, earlier this year, she presented sensual and erotic collaborative photographs celebrating a sex-positive perspective on masculine femininity – a love letter to her transnational LGBTQIA+ community. The project features Sabaliauskaitė exploring her identity as both an immigrant and gender non-conforming lesbian, and is a provocation to listen to the experiences of Queer folks from a wider geography.

For Sabaliauskaitė, inclusion and collaboration are vital, and she is committed to participating in other photographers’ work as much as her own. She hopes this gesture of “building visibility together” will create a chain reaction, helping others feel safe and empowering them to take risks, to push the boundaries of how Queer bodies can be seen and represented. “I always make work with the intention that it will be visible,” she says. “First and foremost, because in Lithuania, there isn’t much. As Queer people, we can’t wait for laws to change; for someone to tell us we can do certain things. We have to take chances, embrace our desires and express ourselves.”

If the past is any indicator, the significance of today’s visions of Queer life will go unrecognised for years. Yet, these artists instinctively understand how vital it is to create a living archive of, and for, LGBTQIA+ people, and the endless and vital ways in which queerness is experienced and performed. Queer culture, like photography more generally, is entering an era in which the mechanics of cultural production are perhaps more meaningful than the final shot. As we contemplate the role of images in our lives, my focus has shifted from ‘Is this good?’ to ‘What might this do for someone?’