Uyghur Community © Carolyn Drake

Gathering hundreds of images and contributors, a new book challenges narratives on photographic history and collaboration

On 13 March 2021, Patsy Stevenson attended a vigil in London for Sarah Everard, a young woman who had been raped and killed by a serving police officer. The event took place during a Covid-19 lockdown in which gatherings were subject to harsh restrictions, so it was not officially sanctioned. Hundreds congregated anyway, and the police violently intervened. Stevenson found herself handcuffed and face-down on the ground, and the next day photographs of her arrest hit the front pages.

In September 2023, Stevenson received an official apology from the Met Police, and was paid “substantial damages”. Her vindication followed a lengthy legal battle but, she told The Guardian, one of the worst aspects of the whole experience had been the photographs, and the way people seemed to perceive them. “Some people were like, ‘Oh, you look so great’, or ‘Your hair looks amazing in that picture’,” she told the newspaper. “But that was a really traumatic event for me and I don’t think people always take into consideration that I’m not a picture, I’m a person.”

Stevenson’s story is thought-provoking in many ways, but for photographers it suggests a responsibility when making images. Photographs of people are exactly that – photographs of people – but somehow those ‘subjects’ can get lost in plain sight. As a new book, Collaboration: A Potential History of Photography, points out: “Photography generally requires the labour of more than one person. Most of the time, however, the participation of the others who share the work, including the photographed persons, their labour and the ways they envision their participation and negotiate the photographic situations of being together through, with, against and alongside photography, are often disregarded or unnoticed.”

The text is a group effort from the team behind Collaboration – Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Leigh Raiford, Laura Wexler, Susan Meiselas and Wendy Ewald – but it draws on ideas from Azoulay’s wider output, which proposes an at times radical rethink of photography. Elsewhere she has written that photographs are “unruly metonymical records of an encounter of those convened around the camera” (Capitalism and the Camera, 2021), and that cameras are “an imperial technology of extraction” (Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism, 2019).

“I would say that the root of my ambivalence about photography, right from the beginning, was the power of the camera over and in the act of representation” – Susan Meiselas

But the authors behind Collaboration include two photographers, both of whom are still active today, and as its subtitle suggests, the project is an attempt to both reshape how we think about images and propose new ways to make and share them. Collaboration is less a condemnation of photography than a thorough reappraisal of how it works and how we have interpreted it, and a bid to find more equitable approaches. As its introduction says: “We hope that this book can inspire you to experiment with and find the joy in being with others with and through photography.”

Collaboration was dreamed up more than a decade ago by Meiselas and Ewald, who have both worked with photography for over 50 years and have long had concerns about the medium’s power dynamics. Meiselas’ first major project, Carnival Strippers, included extensive interviews with the women she was photographing, for example, while in Portraits and Dreams, started in 1976, Ewald handed cameras to children and asked them to shoot their own lives.

“I would say that the root of my ambivalence about photography, right from the beginning, was the power of the camera over and in the act of representation,” says Meiselas, who joined Magnum Photos in 1976 and became a full member in 1980. “It was right away problematic for me, and I know it was for Wendy too. We’ve known each other for a long time and, one time when Wendy was staying at mine, we started to reflect on our practice. We found we had similar reference points, and that was very interesting to us. That was an important premise, so we stayed in touch on it, and really reflected on it over the years.”

“Then we started to think, ‘Well, who’s going to write about this?’” laughs Ewald. “Because we knew it wouldn’t be us. We met Ariella at around the same time, and both instinctively said, ‘OK, we have to talk to her’, because she seemed to match and complement the ways we were thinking. We had been focused on our own timeframe, on becoming makers and the work we had seen around us, but she forced us to think about deeper history. We started to see real potential for the project to grow, so we invited Laura and Leigh to join.”

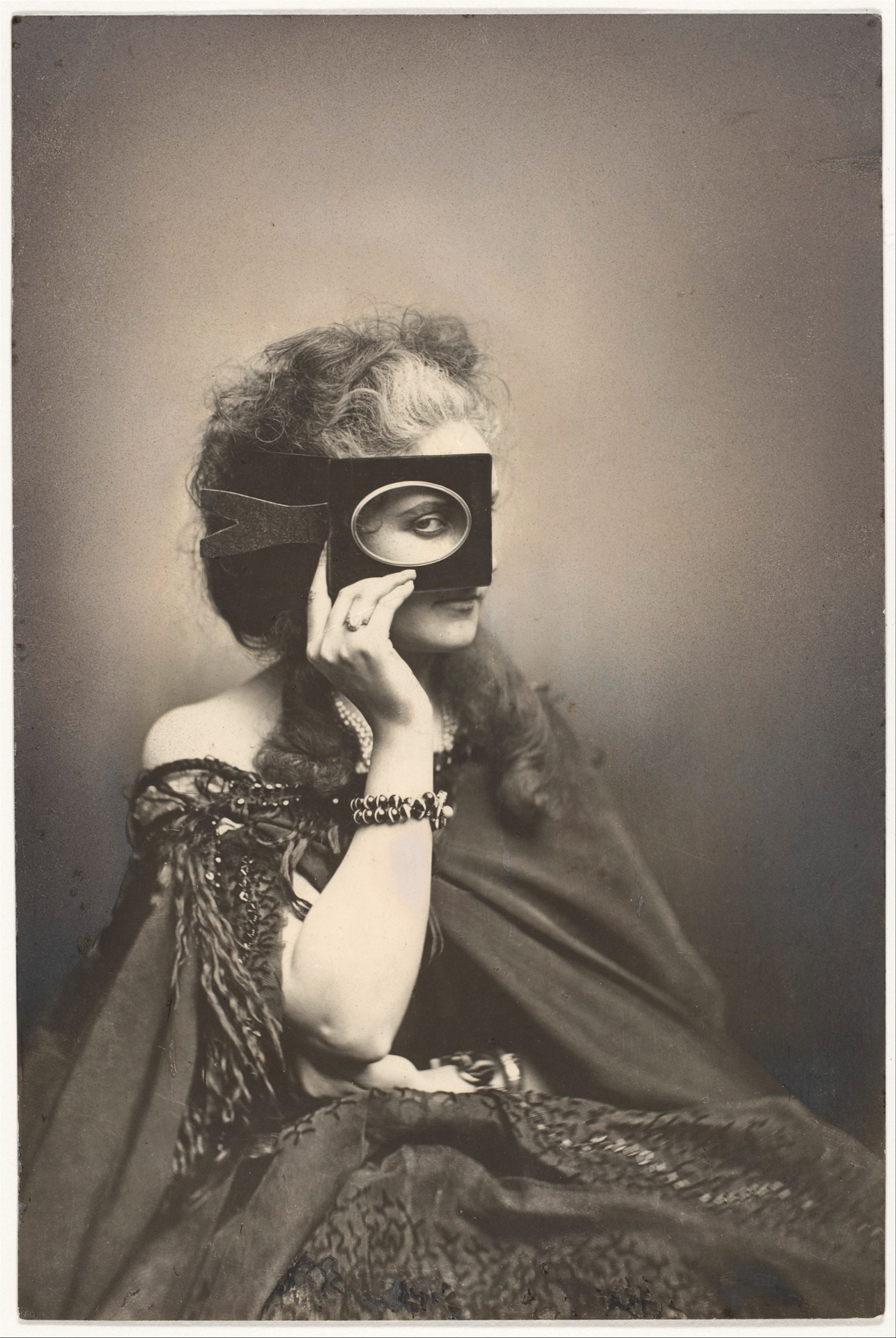

The finished book includes images dating back to the start of photography, from 19th century images of female ‘hysterics’ taken in Salpêtrière Hospital in France through to Dorothea Lange’s iconic images of the ‘migrant mother in California’ and beyond. As the accompanying texts point out, these images are iconic yet somehow unseen, the people they depict made visible yet also overlooked. The ‘hysterics’ are seen in terms of symptoms rather than as women or even individuals, while Florence Owens Thompson in Lange’s famed image is described by her social position, and usually deprived of her name.

Collaboration includes a quote from Owens Thompson, in which she eloquently explains why she disliked her portrait. “I’m tired of being a symbol of human misery; moreover, my living conditions have improved,” she states. “I didn’t get anything out of it. I wish she hadn’t taken my picture… She didn’t ask my name. She said she wouldn’t sell the pictures. She said she’d send me a copy. She never did.”

The book also includes a spread on the portraits of ‘Papa’ Renty Taylor and his daughter Delia, which were at the centre of a milestone lawsuit against Harvard University in 2019. The case was brought by Tamara Lanier, who demanded restitution of the daguerreotypes of her ancestors on the grounds that the images were seized from them while they were enslaved; these images were made through a collaboration between Louis Agassiz, the head of Harvard Scientific School, who attempted to use photography to support his racist beliefs, and the photographer JT Zealy. A quote from Lanier in the book states: “For years, Papa Renty’s slave owners profited from his suffering, it’s time for Harvard to stop doing the same thing to our family.”

The changing dynamic

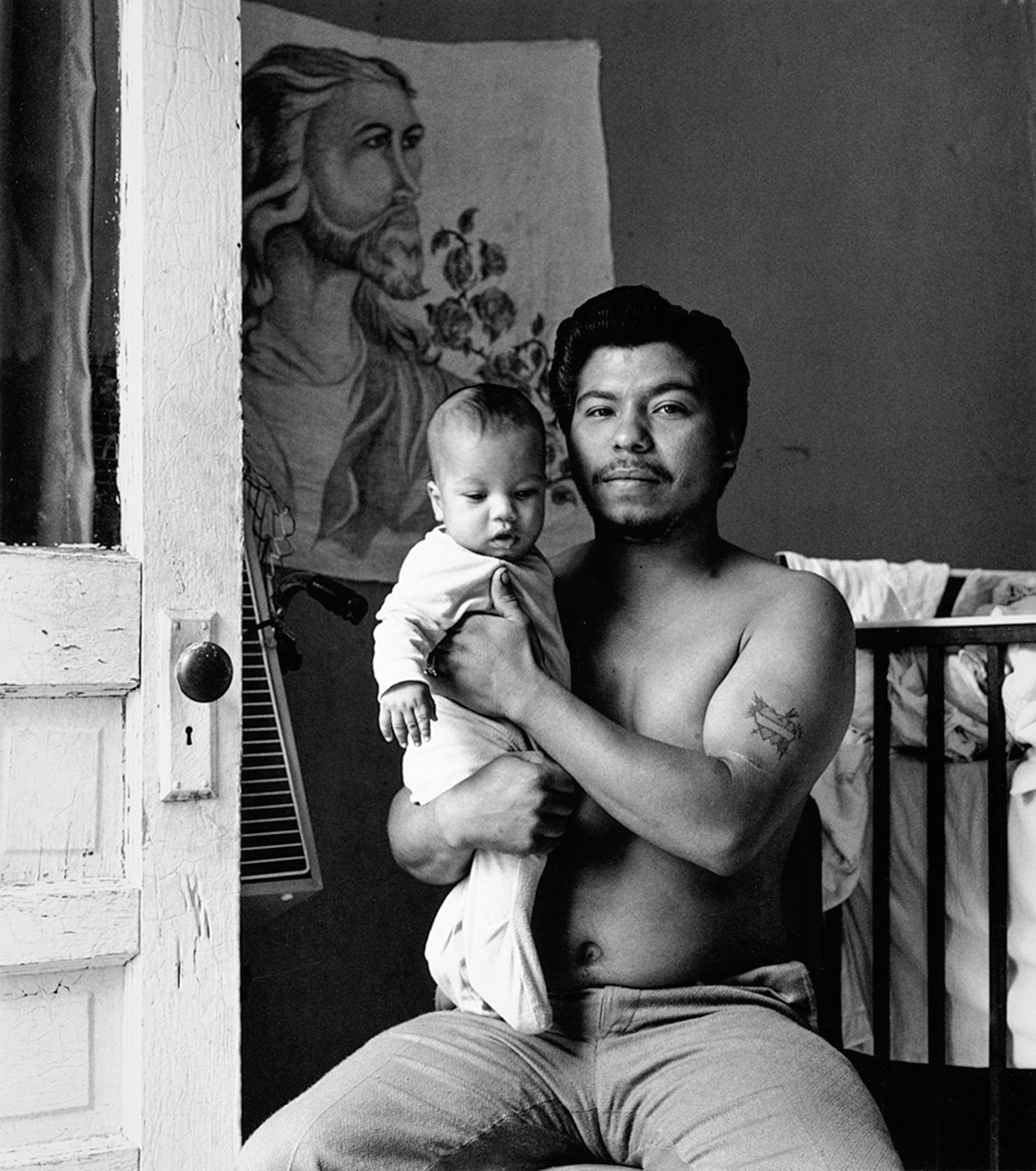

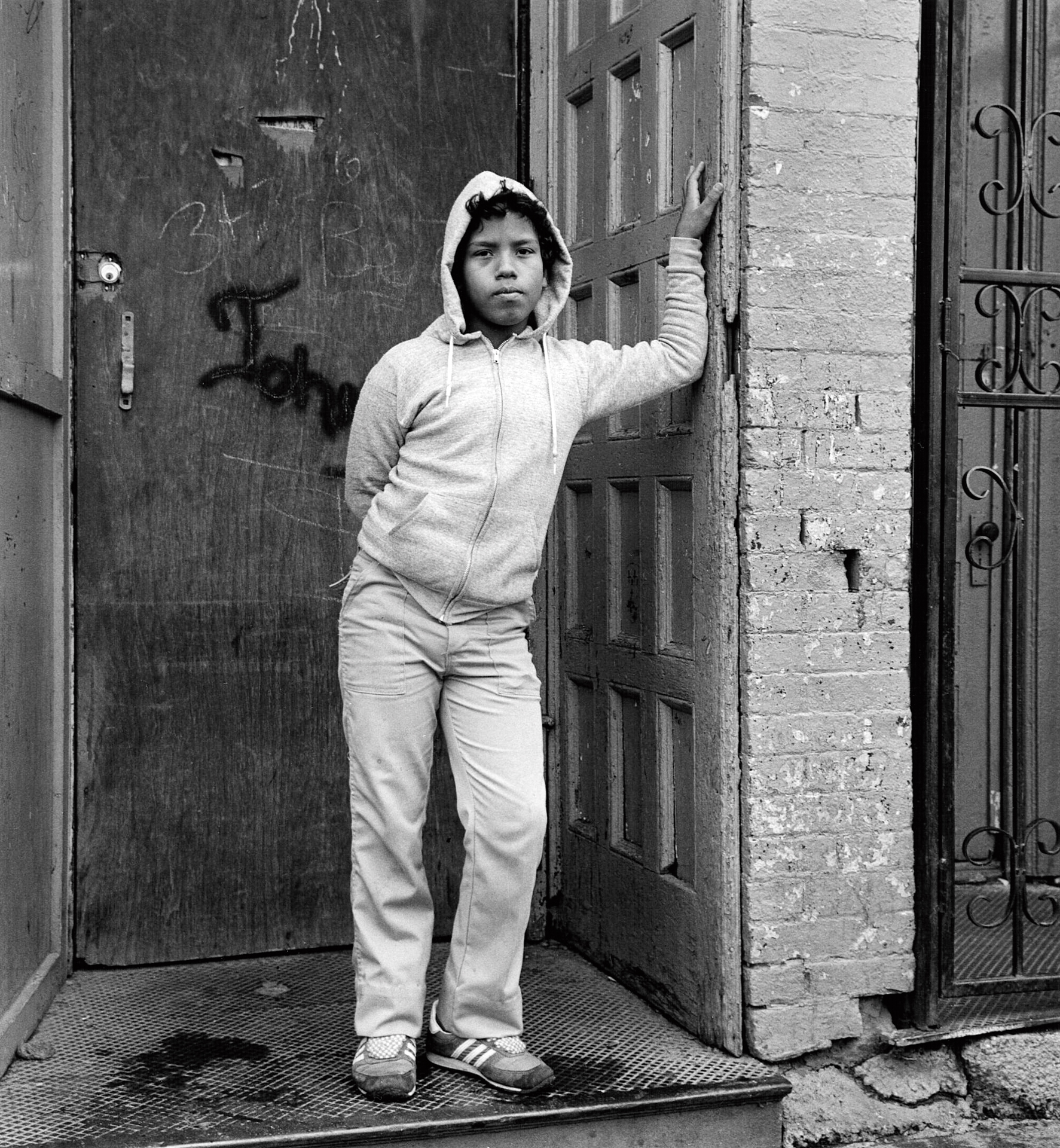

Each chapter in Collaboration is arranged chronologically, but the book also features plenty of contemporary work, more positive examples of which include series by Meiselas and Ewald plus self-portraits by Nona Faustine, collaborative portraits by Endia Beal, shots gathered from Iraqis by Geert van Kesteren after the Iraq War, and Carolyn Drake’s participatory work with the Uyghur community in China, in which they drew on her images. Each project is given a spread and, where possible, the accompanying texts include comments from the people in the images and their names, as well as comments from the photographers. There are also texts by writers such as Abigail Solomon-Godeau, David Levi Strauss and Mark Sealy, plus voices from a new generation of thinkers.

“We have not stopped with the photographers’ ‘intentions’ or ‘statements’, but rather we look at those photographic events as they unfold over time,” explains the book’s introduction. “Attending to the mode of participation of the photographed persons, in particular, enabled us to reconfigure also the participation of the photographers, not as solo masters but rather as parties to the event of photography. We have refused to diminish or deny the collective effort.”

This approach de-centres the photographer, and the eight chapters emphasise this with titles such as The Photographed Person Was Always There, or Reshaping the Authorial Position. Other ‘clusters’ draw attention to more negative uses of the camera, with tags such as Sovereign and Civil Power of the Apparatus. This de-centring and re-reading of photographers’ work was not always easy for the featured image-makers to accept. “When the writing was edited, we always went back to the photographer,” says Meiselas. “And there were some who felt that the writers had not understood their work. It was challenging for them to feel not seen in the way that they see themselves, especially if they’re more used to being celebrated.”

“But that was very deliberate from the beginning, the idea of it being first person from the photographed person, and the photographer, and of having an additional commentary or interpretation or consideration,” adds Ewald. “We were trying very hard to keep those balanced, to have the voices come from all sides.”

Collaboration picks out some cautionary examples such as surveillance shots by Prague’s secret police, as well as more positive approaches, such as LaToya Ruby Frazier’s community-based work. But the book is not intended to pass judgement, or even assume an authoritative take. Instead it argues that photographs’ meanings are never fixed, and aims to open them up further. It intends to sensitise people to what might be inappropriate, explains Meiselas, but also inspire further questions and a new evolution of work. “It’s not a fixed set to be mimicked, it’s much more to inspire the next stage of exploration,” she says.

“Our dialogues, practices and conversations with other thinkers and practitioners across geographic locations have generated many meanings of collaboration in all its various iterations – utopic, dystopic, messy, complex”

Origins of a project

In fact, the project avoided hierarchy more widely, and was put together collaboratively in practice as well as in name. Collaboration did not start life as a book, though this form helps spread it; originally it was a collection of interesting photographic projects, which cohered into groups or ‘clusters’. These sets were assembled into grids, which the group used with students and workshop participants. Finding that these grids prompted open-ended, thought-provoking discussions, Meiselas, Ewald et al decided to make them more public.

Collaboration popped up as a lab at Aperture Gallery, New York, in 2013, for example, then as a more formal presentation at the Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto. Visitors, students and collaborators were all actively encouraged to contribute, their insights helping build the project and book. One visitor in Canada suggested considering images of nature, and what they say about cameras and their use in surveying and commandeering places, as well as people. Collaboration includes a handful of these projects, including Public Studio’s Palestinian Landscapes.

Meiselas, Ewald, Azoulay, Raiford and Wexler also robustly discussed among themselves, and Meiselas and Ewald point out that they reached a consensus rather than achieving group think; Ewald urges me to watch an online discussion made with Milwaukee Art Museum in 2021, to see that Raiford and Wexler “have their own minds” (Azoulay was unable to attend). It is on YouTube and is fascinating, particularly as it ends and the women swing into a clearly familiar debate. As in my interview with Ewald and Meiselas, they riff off each other and jointly narrate stories, like any group used to speaking together. “I’m laughing because I feel like in our last couple of meetings we just had these ongoing arguments, not arguments but debates, about contact sheets,” chuckles Raiford.

“We do have differences of opinion,” Meiselas tells me. “That’s exactly the challenge. For example, Wendy and I are trying to find ways to wrestle through it [photography and its power dynamics], whereas Arielle is sometimes condemning it fundamentally. We’ve tussled that together in a number of ways.”

Of course, achieving consensus is not easy, and that is one reason Collaboration took more than 10 years to complete; in a deeper sense, perhaps, that is why it can never be finished. The introduction to the book ruefully reflects, “we feel we could continue this work for another decade”, but the group decided to hand it over so others could continue the discussions “in classrooms, workshops, community centres, in union meetings and at home”. Similarly, the issues and themes are ongoing for the five authors as the introduction also makes clear.

“Our dialogues, practices and conversations with other thinkers and practitioners across geographic locations have generated many meanings of collaboration in all its various iterations – utopic, dystopic, messy, complex,” it reads. “We are striving for nuance and inviting questions rather than offering final answers. We continue to learn from the work of others and are engaged in ongoing conversations with those who are included here as photographers, photographed persons, writers and other contributors to the event of photography.”

As Ewald and Meiselas tell me, the discussion is also evolving because the media landscape is changing. With digital imaging, the internet and social media, it is no longer only ‘hysterics’, ‘migrant mothers’, or young women under forcible arrest who find their images taken and circulated beyond their control. It is all of us – and most of us are also complicit. “It’s important, because people with camera phones have absolutely no sense that there is any responsibility,” says Meiselas. “There is no social contract at all.”

Collaboration: A Potential History of Photography by Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Wendy Ewald, Susan Meiselas, Leigh Raiford and Laura Wexler, is out now (Thames & Hudson)