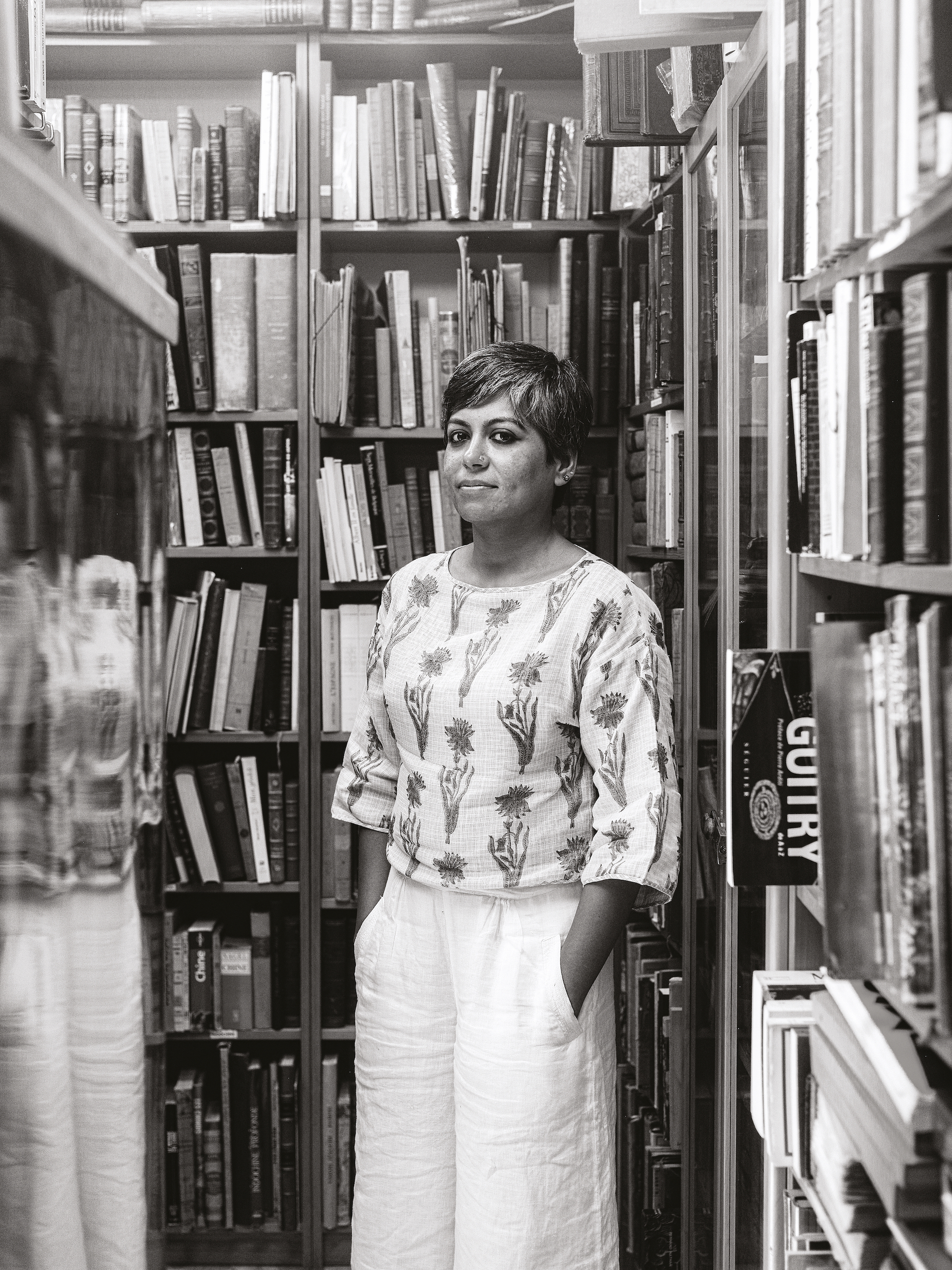

© Akshay Mahajan

The Indian photo expert talks through her career in non-traditional spaces – and reveals how exhibitions can act as ‘portals’ for equity

Based in New Delhi, Tanvi Mishra is a curator, photo editor and writer. She curated the Louis Roederer Discovery Award at Les Rencontres d’Arles 2023, and has worked with the curatorial teams at BredaPhoto Biennial, Photo Kathmandu and Delhi Photo Festival. Part of the first International Advisory Committee of World Press Photo, she has also contributed to publications such as Why Exhibit? Positions on Exhibiting Photographies (Fw:Books, 2018). Mishra is on the photo editorial team of PIX, a South Asian publication and display practice, and is the former creative director of The Caravan, a journal of politics and culture

I come from a practice-based background, I didn’t study art history or curatorial practice. It’s always been learning by doing. Something we discuss amongst colleagues back home is the hierarchy we see in institutions. The goal would be to dismantle those hierarchies in favour of something more collaborative. In an artist-curator dynamic, that is crucial for me. I feel that to be able to comment on someone’s work, I have to earn my place, and that has to be through the relationship we build together. Otherwise, who am I to come in and tell you what you should do?

I’m not attached to any one institution in a curatorial capacity. Most of my curatorial work has been with festivals, so working in non-traditional spaces has been the norm for me. I prefer working outside the white cube, it’s more challenging. As I’ve grown as a curator, I’m drawn to the possibilities of the physical movement of the body in the exhibition space. Looking up and down, maybe even straining to see. There’s so much potential in a three-dimensional space.

“I feel that to be able to comment on someone’s work, I have to earn my place, and that has to be through the relationship we build together”

The word ‘diversity’ is circulated a lot, and there is wider representation than before. Things are slowly changing. But even now, you’ll find lists with maybe 10 to 20 per cent of the artists from outside the west. Very rarely do we see majority representation, say to the tune of 80 per cent [as in the Arles Discovery section this year]. I felt we needed to have that precedent. It is very important we have a majority of non-European, non-American representation, allowing for nuances to emerge rather than generalised perspectives.

While working with artists in the Global South, the possibilities are very different. Of course, the whole sociopolitical context completely differs, but I mean more in terms of resource. We don’t have patron institutions in the same way as the west, and we don’t have access to the same technical equipment all the time. For example, when we were working with printers in New Delhi or in Quito [for Discovery] the options for printing depended on availability. When paper is often imported, it is either at limited availability or at unaffordable prices. There are huge disparities in the production process itself.

Can we ever really have an equal world? That feels like utopia. History has shown us that things are always shifting, and the once oppressed can also become oppressors. For example, India was colonised but now it has colonised places like Kashmir. India’s independence was from British rule, but the postcolonial landscape continues to have caste hierarchy that was already in function for thousands of years. For the oppressed, it marked only a shift in the oppressor – from the British coloniser to the dominant castes – not a true moment of liberation. We all continue to have complex identities. In the west I am seen as a person of colour, a minority voice, but back home I am from a dominant caste. For me, these complex positions can inform our movements towards equity.

“Visiting an exhibition can be a collective experience. Everyone’s having this private viewing, but you’re also aware that there are others around you”

There are so many layers in the power relations of making an image. What happens in that encounter? There is this assumption around the power of visibility, the idea that people will get justice because they will be seen. But does becoming visible ensure empowerment? I’m not convinced about that. I’m interested in the simultaneous notion of refusal, that we get to choose not only what (part of us) we show, but also what we refuse to be seen.

Visiting an exhibition can be a collective experience. Everyone’s having this private viewing, but you’re also aware that there are others around you. It’s similar to when you go to the cinema and everyone laughs together. There’s power in that collectivity of the public. I’m interested in entering into a dialogue with the audience, I believe they have agency. People are intelligent, if you give them the space they want to respond.

What you do with the image, the activation of the work is crucial. If we think of photography as a portal, perhaps the exhibition can offer one point of encounter for a dialogue.