With the physical space closed for renovation, Fotomuseum Winterthur’s digital curator reveals how ASMR livestreams and ‘sludge content’ are keeping online momentum high

Marco De Mutiis, digital curator at Fotomuseum Winterthur, wants the photography world to “stop whining”. Each recent wave of technology has prompted cries that the medium is dead, he says, citing Photoshop in the 1990s, Flickr in the noughties, then smartphones, Instagram, TikTok and, most recently, artificial intelligence. He has had enough. “All I hear when talking about digital images is people saying things are getting worse,” he says. “That’s a spirit I want to avoid.”

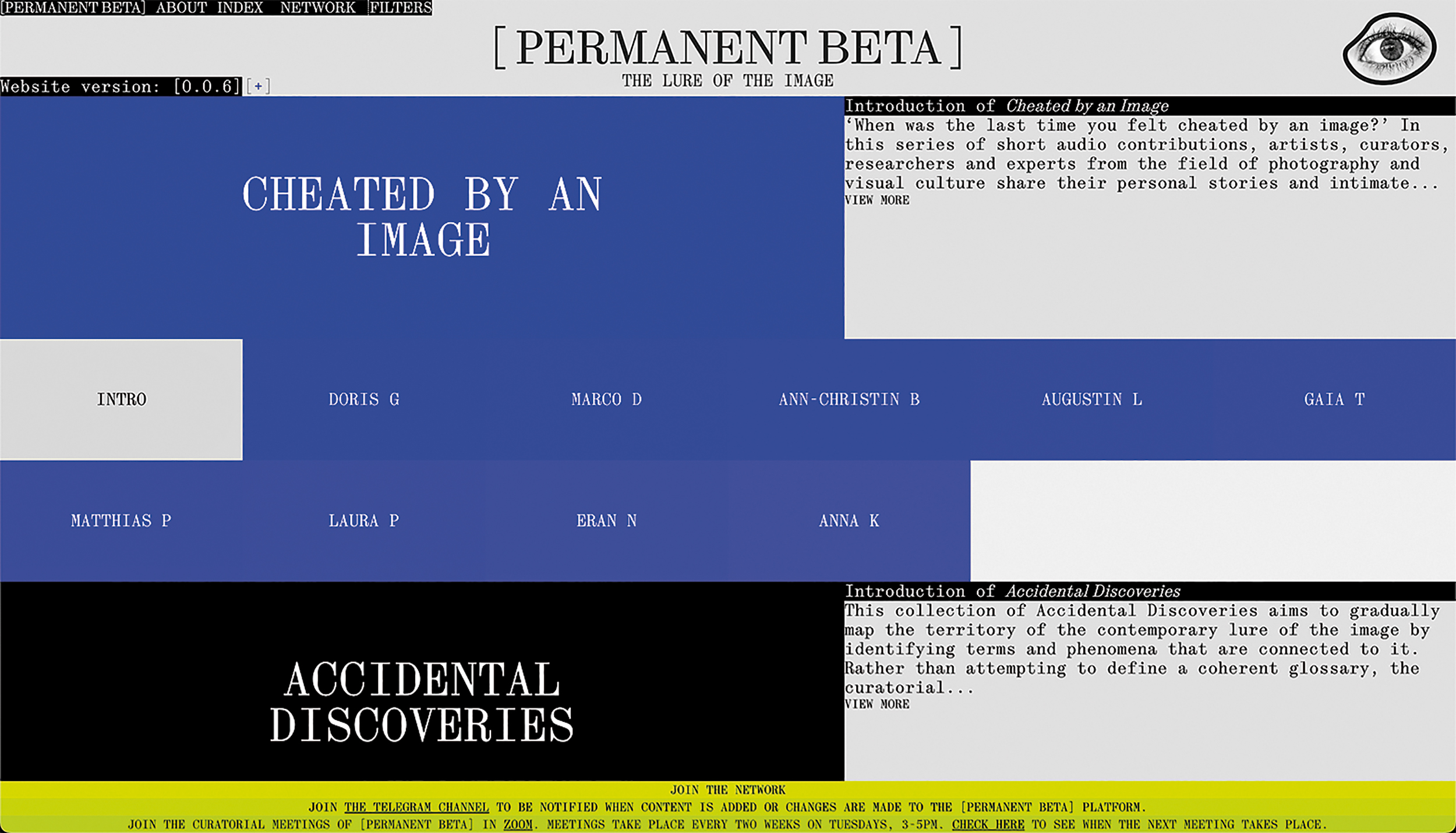

But maybe De Mutiis would say that. His job is to find forward-thinking uses for the Swiss institution’s online space, reclaiming the internet rather than resisting it. That stepped up a notch earlier this year when Fotomuseum Winterthur’s bricks-and-mortar gallery closed for renovation, bidding farewell in July with a weekend event called Balladen zum Abschied (Farewell Ballads). Stepping up to fill the gap. Permanent Beta is an online platform on which staff can post research and ideas, often in the form of podcasts or artist livestreams. It will culminate in an exhibition when the physical space reopens in 2025.

“Generally as curators we are trained to produce final texts that speak with a detached, almost scientific voice,” De Mutiis tells me. “In Permanent Beta we’re bringing in personal reflection and learning. That personal aspect is something that I enjoy, when you hear interviews about the process behind artists’ work. As this evolves over the two years, I’d like to give an insight into the curator as a human being.”

In an audio-led section, curators talk about occasions they have been cheated by an image. De Mutiis recalls absent-mindedly buying a birdhouse from Amazon, only to find out that the giant package was being shipped from the US to his home in Switzerland. “This image suddenly became connected with supply chains, labour issues, carbon emissions, algorithms…” he recalls. “It was like a movie scene playing out in my mind.”

Elsewhere, the artist Dina Kelberman hosts a weekly livestream as part of her ongoing Sponge Project, playing videos of people ripping, squelching and squidging sponges. The sounds – which played alone are designed to elicit autonomous sensory meridian response (ASMR) – create a fuzzy cacophony, which she organises into a spectrum ranging from ‘soothing’ to ‘abrasive’.

“I’m more interested in seeing what the online space can offer that the exhibition can’t”

The livestreams mimic a recent collaboration between Fotomuseum Winterthur and The Photographers’ Gallery in London called Screen Walks. “These are spaces in which we can see through the eyes of the artist; that could not exist in a physical exhibition,” De Mutiis says. “We’ve also attracted a small community of people who join and interact with the artist. That creates a new kind of participation, and a new space for seeing art as a work-in-progress. So there are many things that open up if we experiment with online spaces.”

It all feels surprisingly lo-tech. Permanent Beta’s aesthetic echoes the online world around the turn of the millennium – think early Wikipedia and dial-up internet – and there is certainly no hint of virtual reality or artificial intelligence. “This was a conscious decision,” De Mutiis explains. “It felt more experimental [to omit these features]. During the pandemic, we saw a lot of museums recreating physical spaces through 3D modelling and CGI. That just felt like copying one space into the other. I’m more interested in seeing what the online space can offer that the exhibition can’t.”

De Mutiis says he still loves the reallife space of an exhibition, but points to its limitations and the fact that, when it hosts online videos, memes and gifs, they are squeezed and stabilised. “A lot of museums have struggled with wanting to be more up-todate with these sorts of contemporary images without updating their infrastructure. That is the starting point of Permanent Beta.”

He would “absolutely” like to see similar initiatives from large public institutions, which would help make their projects more accessible, but questions whether their funding structures would allow it. Few galleries have a dedicated digital curator, though institutions like the Whitney Museum of American Art and private collections such as the Julia Stoschek Foundation have been leading the field for several years. “I understand why [there are few digital curators], but I find it sad,” De Mutiis says. “It doesn’t take much to start livestreaming. So many lockdown-inspired projects have been cancelled in favour of the physical space.”

Admittedly the experimental, sometimes spontaneous nature of Permanent Beta is brave. The project’s aim, to “show what goes on in the minds of the curatorial staff”, might jar with the authoritative tone sought by major galleries. But the process at Fotomuseum Winterthur leaves space for human error, De Mutiis says: “When you show your process, sometimes your ideas start out wrong or you’re ill-informed. It’s not for everyone.”

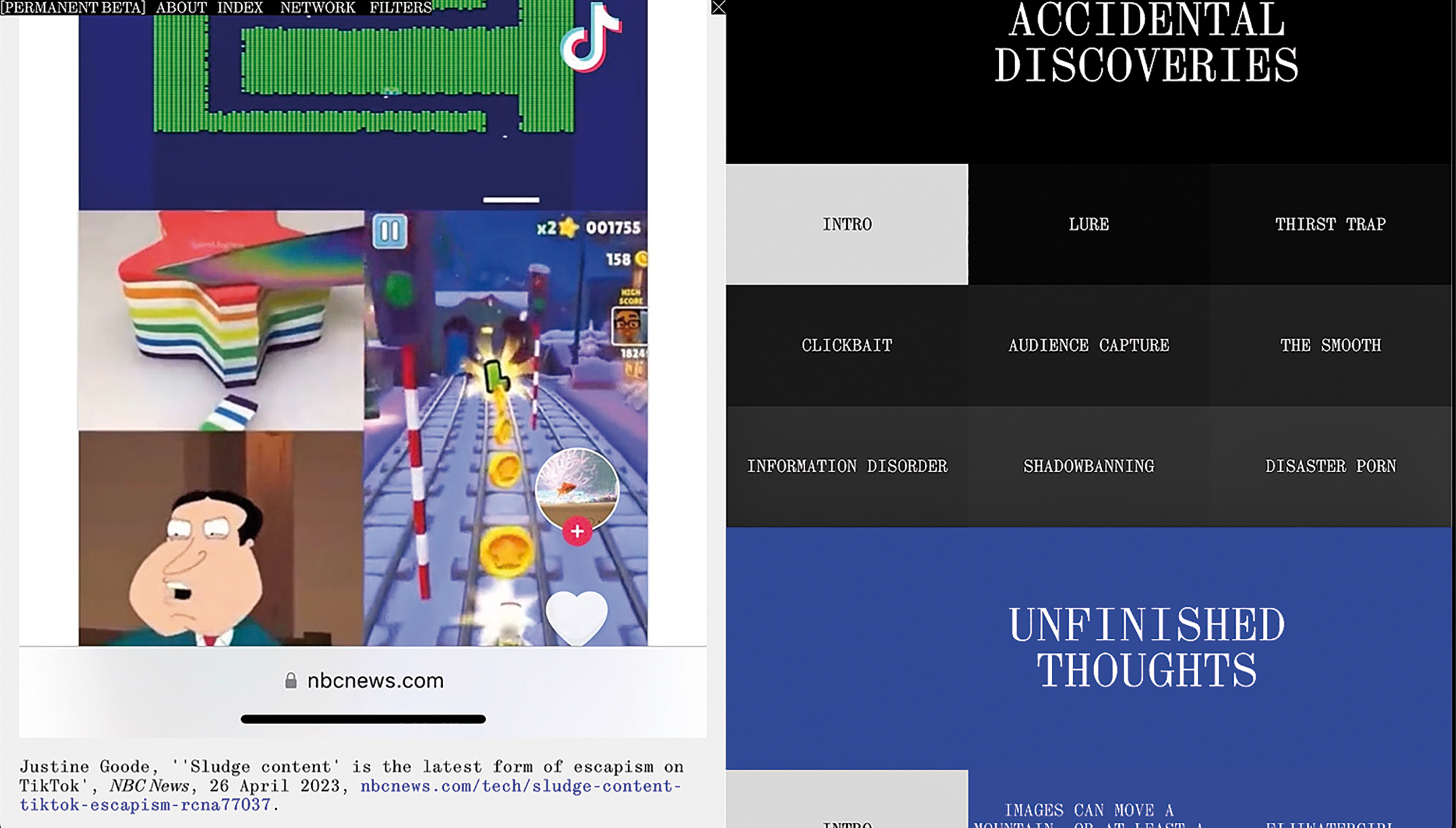

Another section, Accidental Discoveries, is a growing list of sometimes concerning phenomena in online image-making, in which curators pull together definitions of terms such as ‘digitised dysmorphia’, ‘cursed images’ and ‘disaster porn’. Many of them are amorphous or difficult to pin down, and the team draws heavily on blogs and news articles rather than academic resources when feels like you’re going exploring,” De Mutiis says. ‘Sludge content’, a particularly elusive example which involves collaged TikTok videos of seemingly unrelated images, is an aspect of social media that De Mutiis finds particularly troubling. “You don’t have any tension build-up or release, you’re just being hypnotised,” he says. “You’re not only passive, but it creates a dependency. We’re letting our brains be mushed.”

Much of De Mutiis’ creative practice involves pondering where the limit is or what comes next – how much more human beings can take before our minds actually turn to sludge. In other words, while the trends could be concerning, there are tools that can empower and inspire artists: “If we think about this as something that we can use and appropriate, it’s very liberating.”

And that, says De Mutiis, is where some in the photography world are going wrong. Internet image culture has long permeated contemporary fine art, but in photography, critics are quick to declare the demise of the medium. “I don’t know if people are afraid of change, but they shouldn’t be,” he says. “After all the developments to the photographic image in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries, this medium has much to contribute to the discourse. We almost have a duty to engage with these new forms of images, not resist them. We should be in the driving seat.”