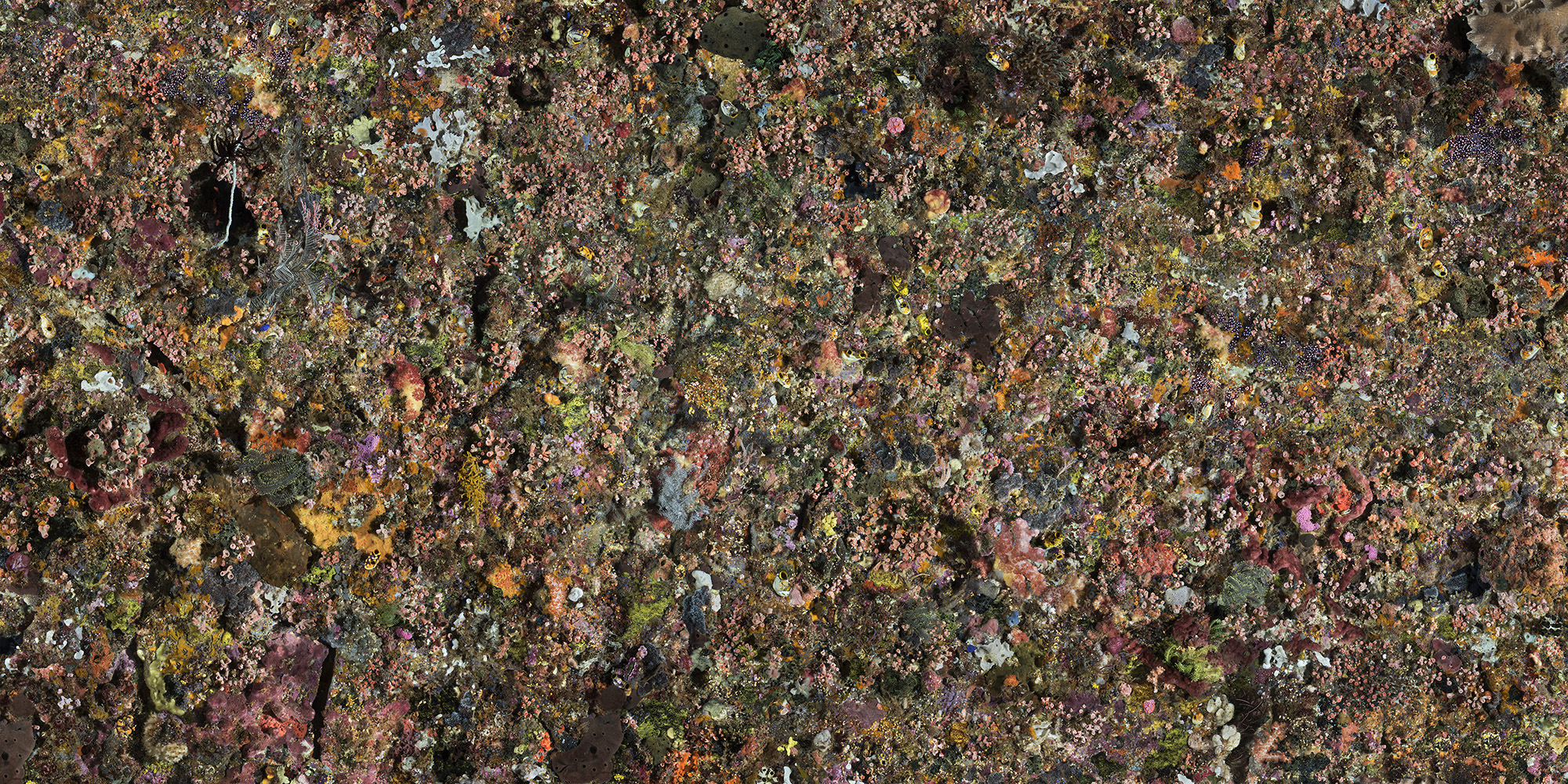

Pengah Wall #1, Komodo National Park, Indonesia, 2017. All images © Edward Burtynsky. Courtesy Flowers Gallery, London

The Canadian artist has captured our scars on the planet for over four decades. His largest ever show is a rallying cry with multiple voices

Edward Burtynsky is standing in front of the most ambitious and labour-intensive photograph he has ever made. It is a blanket of golf-ball sized orbs and growths in pink, orange, green and brown, unfurling across an entire wall in London’s Saatchi Gallery.

Pengah Wall #1 is an underwater photograph – or rather, a digital image composed of around 200 individual shots – made off the coast of Komodo Island in Indonesia in 2017. Burtynsky stands back slightly and admires the coral, its fleshy, sprouting texture lending a sense of alien vitality. He mentions the work of painter Jackson Pollock; the idea was to emulate the motion and energy of his canvases in the image. “Abstract Expressionism was one of the things I loved in 20th-century art,” the Canadian photographer says. “That there is no singular central point in the images, and their all-overness, texture and modulation – the whole surface has been considered.”

In terms of production cost, the reef image dwarfs anything else that Burtynsky has made. Six photographers and six professional divers ventured to a depth of 60 feet to divide the coral into a grid; they then moved slowly up and down making photographs of the shifting seabed, returning intermittently to a boat with a 30-strong crew to examine their pictures on screen. The swirling currents presented a challenge, as did needing to illuminate the reef manually. A Photoshop expert then worked for three months to stitch the final image together, meticulously selecting when to splice and blend each tendril to create a smooth, almost one-to-one scale composition. “It’s speaking to biodiversity on a level that is almost hard to comprehend,” Burtynsky reflects.

The extent of human extraction and infrastructure, and their impact on the planet has been Burtynsky’s subject for over four decades. As a first-year student at Ryerson (now Toronto Metropolitan University), he was tasked to ‘go out and find evidence of man’, sparking a curiosity in the environment which picked up pace in the early 1980s, when he stumbled across an enormous mine while wandering around Pennsylvania. He has since made pictures of industrial ingenuity – and fallout – across North America, Russia, Kenya, Iceland, Saudi Arabia, Australia and scores of other countries. Extraction / Abstraction is his largest show to-date, featuring 94 large-format images, the immersive mural work In the Wake of Progress, an augmented reality piece (which Burtynsky calls “photography 3.0”) and a display of equipment and shoot ephemera.

The extraction theme in Burtynsky’s work is clear, but what about abstraction? He continues to draw parallels with the New York School, and their “treatment of the whole surface as active and the compression of space” which led the photographer to start viewing his own images as canvases. Conversations with longtime friend and Extraction / Abstraction curator Marc Mayer led to a unique approach at the Saatchi, in which Burtynsky’s images are grouped according to harmonies in colour, texture and visual language rather than series or location. “These first three rooms are almost as if you’re going through a painting show,” Burtynsky says. And the 60 by 80 inch prints “allow you to have more of a bodily experience of the work. The smaller it gets the more cerebral it gets – here you’re enveloped in the space.”

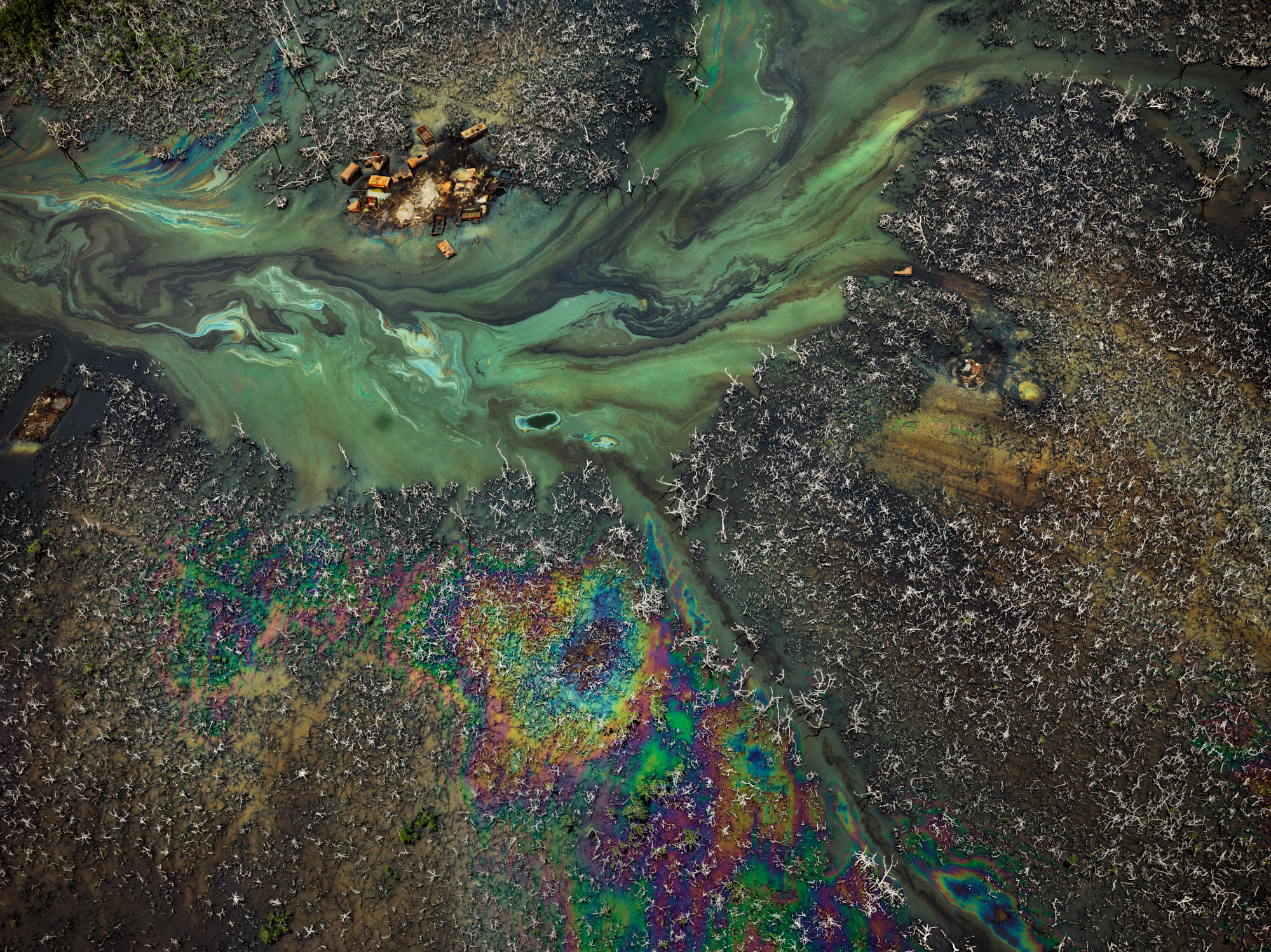

Burtynsky’s projects like Quarries, Water, Oil, Salt Pans and African Studies often comprise pictures from across several locations or, like China, rove around a region and feature several industries, from chicken processing to shipbuilding. The photographs hang in mixed series at the Saatchi, farmland in Spain and Ethiopia alongside Turkish lakes and Mexican irrigation systems. Themed groupings return later in the show, with the rooms titled Agriculture, Extraction, Manufacturing, Infrastructure and Waste. Burtynsky has said in the past that he works in “arcs” or “buckets where I can fit different ideas”. This means that broad topics such as ‘Water’ can be explored in “poetic and interpretative” ways without striving for exhaustive documentation. Here the arcs coalesce, mixing and matching across the globe to dizzying effect – a true representation of the multiplicity of our ecological impact.

One of the aims of Extraction / Abstraction is to create a kind of disorientation – to defamiliarise Burtynsky’s subject matter by transcending geographic and thematic contexts in favour of aesthetics. He wants there to be a sense of “Where am I?” and “What am I looking at?” in the opening galleries, he explains. This is rare in photography, where the first questions asked of a work tend to be “What is it?” and “Where and when was it taken?” The approach puts more emphasis on tone, texture, lighting, and perspective. There is an irony in the fact that curating images like paintings prompts technical questions about photo composition, even while Burtynsky’s longstanding interest in the surreal and the sublime linger in shots of mines, quarries and hundreds of acres of farmland.

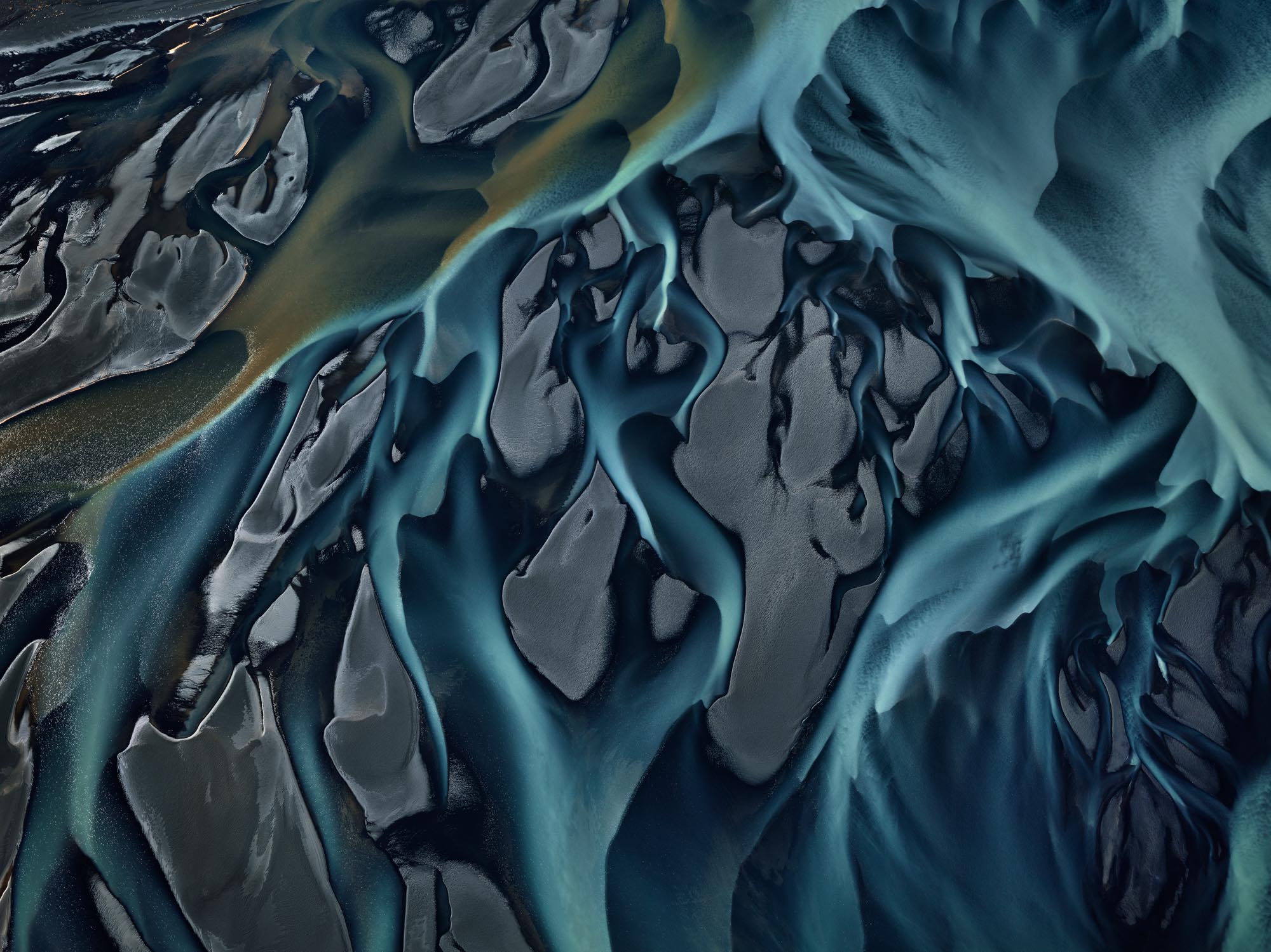

Small tiles of wall text give viewers context on each image, though Burtynsky easily recalls the location and story behind each shot as he guides me through the show. He approaches Thjorsá River #1, Southern Region, Iceland, 2012, an aerial survey of silt formations along the country’s longest river. It’s a rich, inky work which looks part-nautical, part-astronomical – perhaps even computer generated. “This is a river Delta where the glacial run-off is braiding on the final stages of the delta before it exits out into the ocean,” Burtynsky says. “So you get a lot of glacial till that’s in the water so it gives you that opacity… those beautiful opaque tones.” The image is particularly beguiling, with light grey blotches iterated across the print like a painterly motif.

The impulse towards abstraction is clear in Burtynsky’s description – the blurring of the physical landscape’s aesthetic properties with those of the photograph itself. Because of the location’s remoteness and the uniqueness of Burtynsky’s aerial vantage point, describing the image and subject as one makes sense. It is likely that viewers will never see many of Burtynsyk’s natural phenomena for themselves, and with climate breakdown changing the landscape irrevocably, there is an elegiac quality to a show which also asks fundamental questions about photography’s commemorative role.

“We’re in challenging times… It’s tragic that planetary health is becoming a political football”

We continue around the Saatchi, traversing the globe through pictures. Erosion Control #11, Burdur, Burdur Province, Türkiye, 2022 shows human footprints breaking through white salt flats, leaving hundreds of black dots. Burtynsky didn’t quite know what he was seeing from the plane above, he tells me, comparing the landscape to “stretched fish or eel skin”. Again his desire to defamiliarise the landscape into something abstract or bodily is clear.

Lagos is a place of particular fascination. A 2016 photograph shows illegally logged timber floating across down the Makoko lagoon, soon to be exported or driven into the silt to continue the floating settlement’s expansion. The deforestation is devastating, but Burtynsky marvels at the ingenuity required to serve Lagos’ rapidly growing population (which could reach 25 million by 2035). “The whole world has recreated itself on these stilts,” he says. It is a prime example of his work’s latent ambiguity, where environmental destruction sits alongside – and is often indivisible from – the infrastructure needed to sustain our current way of life.

The climate crisis is an inevitable topic on which Burtynsky is often probed. (He recently took part in a climate-themed event with former governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney). It is striking that his image-making has spanned the most intense period of climate awareness, from tentative warning signs to a wailing, terrifying alarm bell. In 2013, he said that “I don’t see myself as a card-carrying activist at all, but I do see myself as an advocate or a concerned citizen for sustainability.” What does he think now?

“We’re in challenging times,” Burtynsky says with a laugh of acknowledged understatement. “God forbid the wrong politician gets in in America, let’s say, and all of a sudden it’s free for all again. It’s tragic that planetary health is becoming a political football.”

But there is hope in his recent work. Pengah Wall #1 is part of Anthropocene, a roving project which aims to progress the environmental debate “by being revelatory and not accusatory”. Nairobi landfill sits alongside thousands of flood-damaged cars in Texas, slum roofs in Mumbai and the lush vegetation of Vancouver island in work which spans a documentary film and an interactive website. “It is about ending on hope – the fact that we still have biodiversity with us,” Burtynsky says.

There is also an eye on the future. The augmented reality project allows visitors to view a rusted car engine from Accra and other scrap objects in rich detail. The equipment display – Phase One and Hasselblad cameras, 3D printed elephant tusks, a range of gimbals and camera stabilisers – points to a love for pushing the boundaries of image-making, as do Burtynsky’s anecdotes about shooting from helicopters and Cessna planes. His photographs may have made the world smaller, showing destinations that viewers might never have previously imagined, but he appears intent on demystifying each composition, despite the reverence for the elliptical world of abstraction.

It is this genuine fascination with the natural and industrial worlds which seems to drive him forward. Burtynsky marvels at the 250km of access shafts drilled into the banks of the Yangtze river to create the Xiluodu Dam; at the Huajian Shoe Factory in Ethiopia; at the order and visual coherence of the Spirit AeroSystems factory in Kansas. “I don’t approach my image-making as conventional documentary, saying ‘I’m going to take you through a tour of how people make salt in twenty images’,” he explains. “I’m interested in the picture, in the landscape and how it’s transformed – the human imprint in that landscape.”

Edward Burtynsky, Extraction / Abstraction is at the Saatchi Gallery, London, until 6 May; New Works is at Flowers Gallery, London (Cork Street), until 6 April