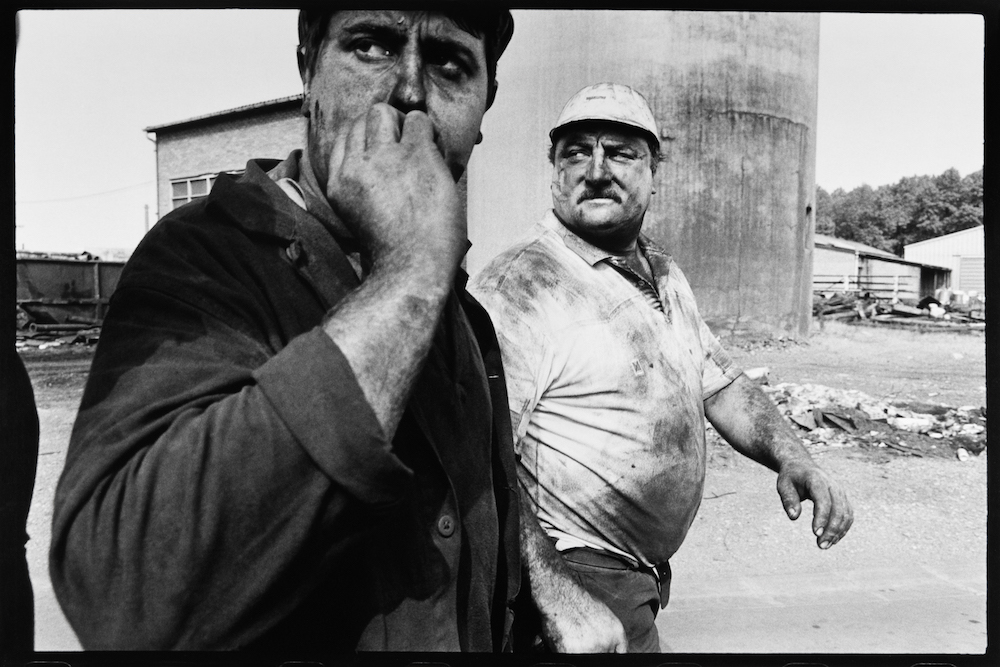

Untitled, from the series Bleus, 1993 © Bruce Gilden. From the Collection of CRP/.

Based in a former mining area in northern France, Centre régional de la photographie is honouring the past to bring photography to the present. Director Audrey Hoareau reveals the innovative ways the centre is reaching out to the local community and beyond

“When I arrived, I immediately put this up,” says Audrey Hoareau, director of CRP/ (Centre régional de la photographie), gesturing to the Hauts-de-France map behind her desk. “For me, it seemed essential to understand where we were situated, and we have a major policy of outreach to different regions. This is our headquarters, but we move around a lot.” She points to a series of dotted locations – “I’m doing my weather girl,” she jokes – to highlight the parameters of the area and how it expanded to fuse with the region below (rural Picardy). She also indicates how CRP/’s influence spans as far as the coastline and the border with Belgium, over two hours in any direction.

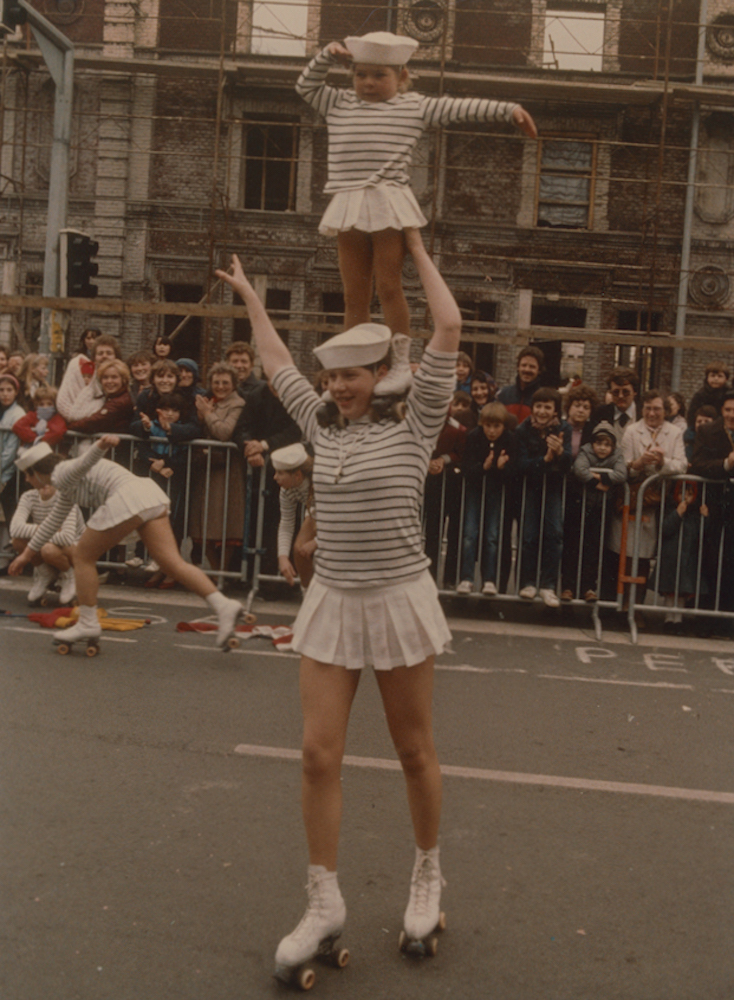

Hoareau is CRP/’s fourth director since its foundation, having previously worked at Musée Nicéphore Niépce in Chalon-sur-Saône and as an independent curator. Her dedication to connecting with the region is also explicitly embedded in the mission of the venue. CRP/ was founded in 1982 and has been at the same location since 1986, in Douchyles- Mines, under an hour from the city of Lille. It began as a local working-class photo club, which held photo competitions that featured carnivals, local rituals, and the region itself, marked by its signature slag heaps. From the start there was an in-house collection, which currently boasts some 9000 original prints, including works from Martin Parr, Bruce Gilden, Zofia Rydet, Josef Koudelka, Stanley Greene, and Sibylle Bergemann.

This inception and maintenance of a collection is exceptional for a centre d’art. The work is mainly black-and-white silver prints from the 1970s and 1980s, although today, CRP/ is interested in broadening to more experimental and technically varied works. The collection is not locked away as CRP/ offers an artothèque (art lending library), including 550 images that individuals and institutions can loan for a small fee (currently €20 per year for six works, each image renewing every two months). Hoareau herself has Claude Batho’s 1970 artwork Marie, Olette hanging in her office.

“We see right away this intention to make art accessible, to democratise photography by the act of living with a work, and it’s a very political project because we’re in a region that is still very left-leaning and communist,” she says. “There’s a tradition of popular education. In the 1980s, there was a huge industrial decline, but there was also a sense of cultural push for the society of tomorrow. It was a little utopian. In the 1980s, a lot of money went towards culture and there were a lot of cultural initiatives.”

The area, stretching from the Belgian border in the east to the hills of Artois in the west, is covered with the history of three centuries of coal-mining. The mining basin perimeter is listed as a World Heritage Site and encompasses over 300 features, including rising slag heaps, which are self-sustaining ecosystems and benchmarks of the local landscape. Other regionally representative markers include extraction pits, railway tracks, mining towns and community facilities.

CRP/ is hard to reach by public transport, necessitating an arduous train/tram/bus journey that does not connect well. There is an ongoing discussion about how to preserve the site but make it more accessible. There is also the need to add space to store the collection, amongst other requirements, since only part of it is held on site. The venue hosts three to four exhibitions a year, with attendance clocking in at about 2800 visitors per year, but outside the walls there are over 50 exhibitions annually with 90,000 visitors.

“To people who feel far away from culture, our door seems made of concrete”

“These numbers reflect a double function,” Hoareau says, pointing to CRP/’s reach. When she arrived as a director, with the 40-year anniversary on the horizon, the question of appropriately honouring the collection loomed large. In 2022, the anniversary year, she negotiated exhibitions of selections from the collection in 16 locations in the region. These were in different types of communities, ranging from the Palais des Congrès in Le Touquet (an affluent area where president Emmanuel Macron vacations) to the literary Villa Marguerite Yourcenar (its writing residency served as a collaboration point on text and visuals), to a huge and popular archive of the mining past in the commune of Lewarde’s Musée de la Mine to Lille’s modular contemporary art Espace Le Carré. There were also cultural events in art schools throughout the region with 478 works from the collection exhibited in a variety of regional venues.

“It was a strong push for the 40th anniversary,” Hoareau says. “But it is ramping us up to something we’d like to make ongoing. We’re continuing this dynamic, and though we did it before, this was our most dispersed, widest reach yet… The ease of working with people in the northern region stems from the heritage of this industrial past: the sense of solidarity is a strong value. We’re not competitive.”

This policy of influence – ‘rayonnement’ in French – extends to the local community as well as the wider region. The areas around CRP/ have high rates of unemployment and alcoholism, a sense of purposelessness lingering in the wake of the collapsed industrial past. Sometimes, CRP/’s reach tries to connect with specific groups, including prisoners, autistic children or unemployment offices, but its broader aim is to attract locals of all sorts. “To people who feel far away from culture, our door seems made of concrete,” Hoareau admits of the rift between the average citizen and the average art-lover.

As a means of extending the space and making its activities more accessible, CRP/ built a pop-up pavilion for school workshops called La BOX. The stand-alone building’s frontage is a glass window so passers-by can see what is going on, making the sense of transparency as symbolic as it is literal. CRP/ also tries to bridge the gap by having artists take part in activities rather than simply hang their work on the walls. The cliché of the artist as individualist is reframed here.

“In the current French cultural and political landscape, we ask a lot of artists,” Hoareau notes. “There’s a sense that artists can’t just create, they owe things to society too. We are pushing them in that direction and it’s a political choice, including via grants they receive. I sincerely believe in these projects but not everyone’s work or disposition is cut out for that. For some artists, exchange is part of what they do. We have to figure out who can, and who cannot. I would never force anyone to do it. We are a support system and we respect the artistic project.”

This summer, the museum remained open in August, a month in which much of France effectively shuts down every year. It was a test run to give people somewhere to go and workshops to try, since some in the area do not necessarily have the means to travel for summer vacations. “We are conscious of the societal challenges of the region, and the centre d’art has a responsibility at several levels: what we say through our exhibitions, and making what we propose accessible in our immediate environment,” says Hoareau. “We must continue to raise the centre d’art to the next level, to have a referential position within the sphere of photography and contemporary art. Our programming has to achieve both aspects.”

This commitment to the community includes maintaining a high artistic standard, with each initiative carefully weighed up before getting the green light. “Not just exhibitions, but our cultural and educational programming, everything adjacent to the exhibitions themselves, to greet the public,” says Hoareau. During August, CRP/ hosted movie screenings as well as workshops with the artists whose work was being exhibited, notably silkscreen printing and cyanotype ateliers. “Our decision to stay open this summer when most institutions close – us included previously – I don’t know what it will yield,” mused Hoareau, prior to the opening. “But we’re going to try, and not cling to the statement ‘We’re closed because no one is around’. We posit: ‘No one is around because we’re closed’.”

The work recently on show also confirms how closely CRP/ respects the region, and how much it wishes to champion it. The institution launched a competition to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the mining basin’s Unesco listing as a World Heritage Site (as well as its own 40th anniversary), asking artists to propose how they would work in the area. The competition attracted nearly 150 applicants and the four winning photographers, selected by a jury, all won commissions to present a new take on the physical and social landscape, by using experimental techniques. The exhibition is titled En creux / Commande photographique sur le Bassin minier (In Hollow, Photographic Commission on the Mining Basin), and features work by Clément Brugger, Isabella Hin, Hideyuki Ishibashi, and Apolline Lamoril.

Brugger’s laser engravings of images adorn a species of local wood, all cut from a single tree trunk and leaving the bark visible. Hin focuses on the miners’ ‘shower room’ and the blue uniform which is sidelined as the miners wash but is here seen wet, torn and distorted in large format ultra-glossy prints. Japanborn, France-based Ishibashi spotlights 12 slag heaps in gum bichromate prints and produces pigments collected from their individually biodiverse settings, displayed alongside his scientific measurements and catalogued empirical approach. Lamoril examines the rabid fan culture around the football club RC Lens, using 1990s archival material of the working-class supporters and their spirit of solidarity, alongside images of sports gear conserved at the National Sports Museum.

“You don’t always have to speak about the region to speak about the region”

In autumn, the programming pivots with an exhibition by Robin Lopvet. Lopvet, who also works as a photo retoucher, will show a variety of his tongue-in-cheek works, which remix tableaux by Hieronymus Bosch, still lifes made from scraps of food waste, and much-memed images of dog faces emerging from clouds produced by natural and socio-political catastrophes. The exhibition will examine what Hoareau calls the “image mensonge”, or the ‘lying image’, which has been deformed enough to leave little or no representative veracity. “There’s a ‘LOL’ quality, and the images appear very light-hearted, but in fact they’re dire,” Hoareau says. This will be the first CRP/ exhibition to explore the absurdity of the digital image and the photograph’s capacity to manipulate the viewer – a take which, in the age of AI and ChatGPT, is highly topical.

Hoareau oversees a wide range of exhibition themes, and describes her approach as one of “symbiosis: an appetite to reread the classical collections and, at the same time, interest in the contemporary image and its challenges”. For her, “there’s no conflict” in reaching for disparate things, and so far she has programmed (in succession) French photographer Camille Lévêque’s visual relationship to Armenia, a group show of four emerging Chinese photographers, an exhibition featuring part of CRP/’s own collection, and vernacular images from the collection of Jean-Marie Donat.

There is no single thread; rather, everything is multifaceted and complementary, which, for Hoareau “reflects the diversity of the production today”. In fact, the mix can yield surprising parallels. Hoareau points out that one of the emerging Chinese photographers, Zheng Andong, investigated the American West and the Chinese workers who went there to look for gold – a theme which resonated well in a French town with a mining past. Andong’s work included an image with a poppy, flora that workers brought to the US from China. This echoes something similar in the CRP/ region, in which Moroccan miners brought strains of mint from home that did not previously exist locally. As Hoareau points out: “You don’t always have to speak about the region to speak about the region.”