All images © Mariusz Smiejek

Photojournalist Mariusz Smiejek has spent much of his life attempting to understand conflict in the North of Ireland. His Belfast exhibition shows the lasting impact of the violence

Growing up in Poland during the 1980s, Mariusz Smiejek had little access to information from beyond the Iron Curtain. In the midst of the Cold War, state media had become a critical component in a highly effective propaganda machine, and a young Smiejek was rarely exposed to the realities of life outside of communist rule. Instead he watched brief, fear-filled snapshots via television news, designed to sow mistrust in democratic nations.

“The bombs blowing up in Belfast, in the UK, was the first live conflict I’d witnessed through the media, through the TV,” the photographer recalls. “And that was strong enough to stay with me. We had a very basic knowledge, but it triggered me to dig deeper later on.”

Although he didn’t know it at the time, the images that impacted Smiejek so markedly were taken during The Troubles. The violent sectarian conflict between unionists loyal to the UK and nationalists in favour of an independent Republic of Ireland lasted for 30 years, and led to over 3,500 deaths. Though the violence officially ended in 1998 with the signing of The Good Friday Agreement, pockets of resistance remain on both sides.

Now 45, Smiejek has been living in Northern Ireland since 2011, when his desire to understand The Troubles finally drew him to Belfast. His work began slowly at first. Through NGOs and peace project workers, he deepened his understanding of the conflict, gradually adding context to the carefully constructed imagery of his youth.

The earliest images from what is now Not Surrendering, a book and exhibition (currently on show at Belfast Exposed), are impactful but perhaps not unfamiliar. At first, Smiejek had captured the parades, bonfires and riots that characterised the tense post-Troubles period, but he was not satisfied with his research ending there. He wanted his work – and understanding – to go deeper.

“The bombs blowing up in Belfast, in the UK, was the first live conflict I’d witnessed through the media, through the TV. And that was strong enough to stay with me. We had a very basic knowledge, but it triggered me to dig deeper later on”

“Me and my ex-partner decided to move to one of the most difficult districts, an area which was under strong IRA [Irish Republican Army] protection,” he tells me. “We wanted to see active IRA members, the neighbourhoods, the people living in these areas.” Smiejek describes living among members of the nationalist organisation as a difficult experience. NGO members, he says, told him it was a crazy plan.

Throughout the following two years, Smiejek forged deep connections with nationalist communities, his own position as a Polish immigrant and outsider affording him an unusual level of trust. His work began to reflect this, becoming both more thoughtful and intimate. But even as the photojournalist came to understand the intergenerational trauma of those around him, it became clear that the violence responsible for their pain had not truly come to an end.

He recalls a conversation with several people that he describes as being associated with the IRA, who he had known and photographed for several years. They showed him an image taken inside a prison. “They said, ‘This is a member of our family, we knew him from when he was born, we spent time in jail together, and you know what? We had to kill him because he talked’,” Smiejek recalls. “‘You come in here with your camera and you say you’re Polish, but you have to remember: we can’t trust anyone’.” The message from this conversation was clear, Smiejek says. And yet, far from driving him away, this thinly veiled threat made him more determined to understand the people on both sides of the border and political divide – and to forge deeper relationships within the communities.

Smiejek switched his focus to Belfast’s loyalist communities, moving to an area associated with the remaining paramilitary groups where strong emotions and unrest continue. “What’s really important for me is not collecting histories or digging into who was responsible for what,” he says. “What’s important is to capture the traumas people are carrying with them after so many generations.”

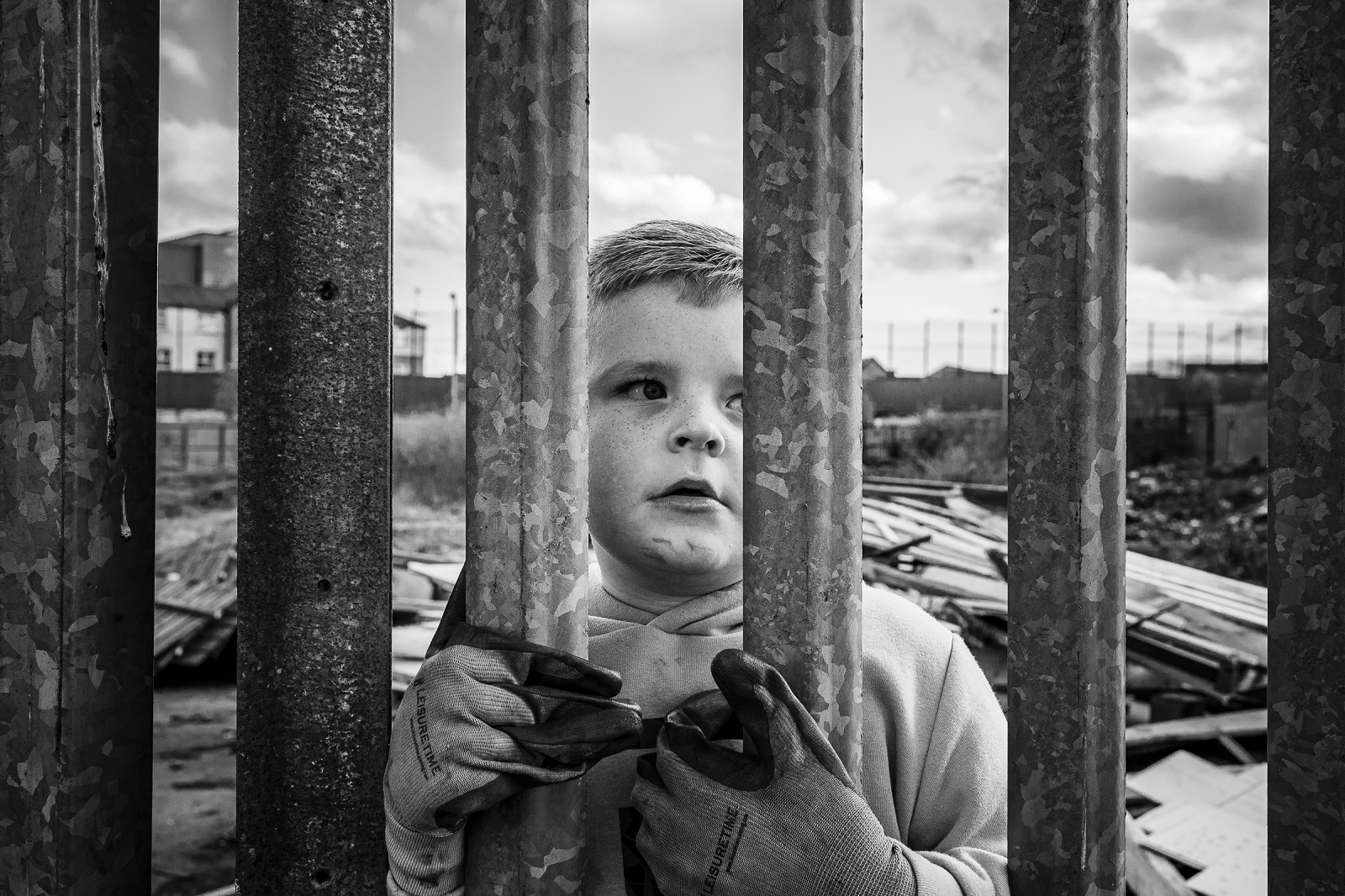

The photographs brought together in Not Surrendering reflect this goal. Unflinching in their portrayals but never entirely lacking in sympathy, the time and research invested in their creation is clear. Firmly in the documentary tradition, the pictures show communities no longer officially engaged in conflict, but certainly still battling with the horrors of their pasts. One image captures Graffiti reading “TAIGS [a derogatory term for a Catholic or Irish nationalist] WILL BE CRUCIFIED”, while another shows a life-size cutout of Queen Elizabeth II amidst a beaming family. An image of a wedding cake features a cake topper depicting a smiling bride and groom, each clutching handguns. Groups of young people are shown frozen in face-offs with riot police.

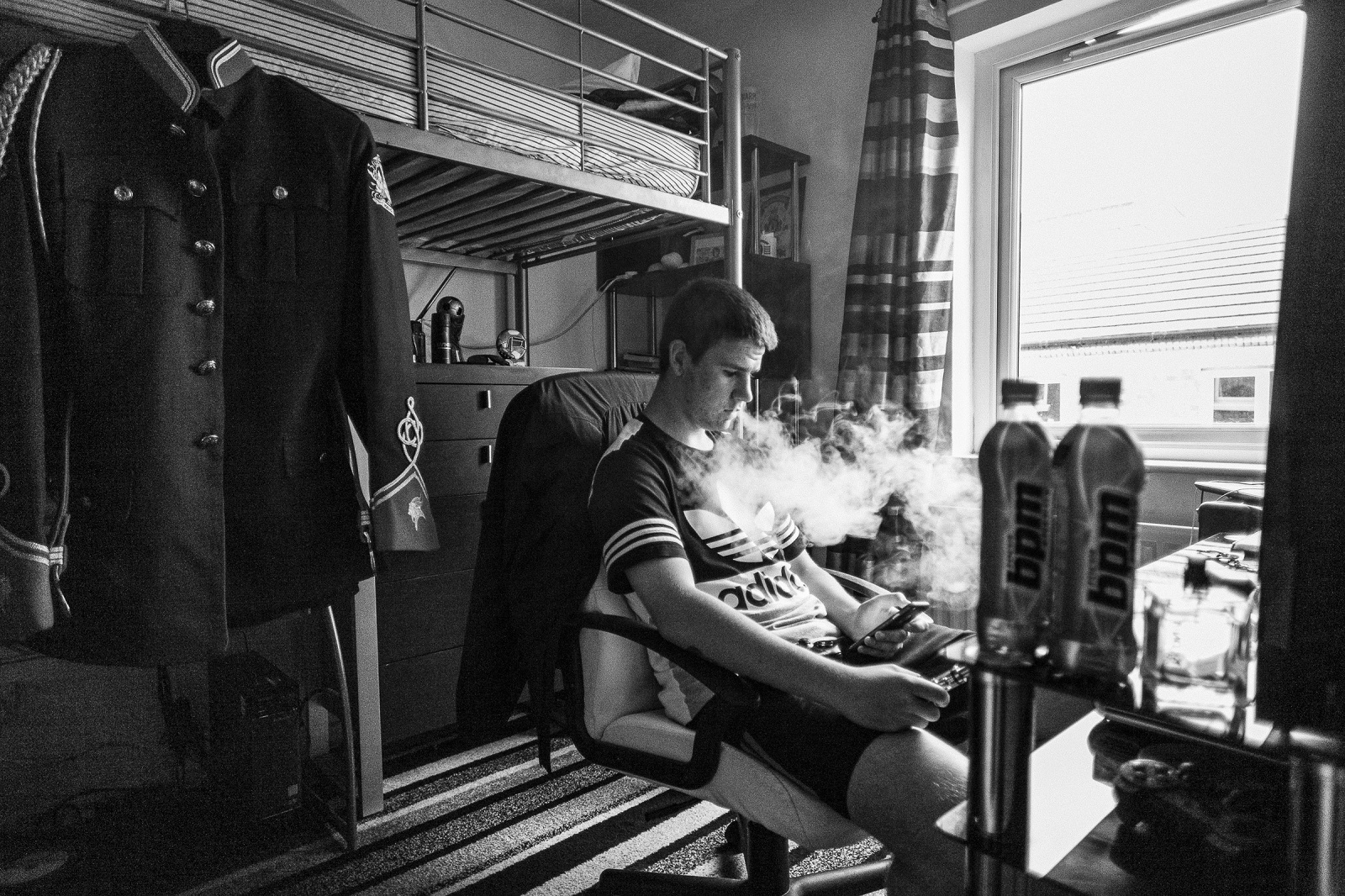

A particularly striking portrait shows a unionist couple at home in their bedroom. On the wall behind them hangs an image of the Union Jack, accompanied by the text “It’s Our Flag Fight for it Work for it”. The man was an active member of the Ulster Volunteer Force, Smiejek says, and had previously spent 22 years in prison for paramilitary activities. “He has since passed away, which is why this is one of few photographs where I can really describe someone as an active member of a paramilitary group,” the photographer explains.

Legal, ethical and safety concerns pertain to both Smiejek and his subjects. He describes conversations with the man in which he was open about his past – and about how important fighting for his country and identity was, even after serving time in prison. The photographer attended the man’s funeral, where saw many more men dressed in loyalist paramilitary fatigues.

What struck Smiejek most about some of these men – more than their uniforms or weapons – was their age. In the 12 years he has spent working across the island of Ireland, it is those growing up in the shadow of The Troubles whose experiences have stayed with him the most. Young people who, by continuing to be drawn into the conflict’s rhetoric by their elders, and by still joining paramilitary organisations on both sides, were ensuring that division and prejudice were passed down the generations.

By bringing the images of Not Surrendering together, Smiejek hopes that he will educate more people about the ongoing involvement of young people in The Troubles’ legacy – and that he will finally contextualise the conflict he witnessed as a child. “When I talk about these things in London people look at me like I’m from another planet,” he says. “But this knowledge is important to understand who we are and where we come from. We should understand how easily people are affected by wars, by colonisation and by conflicts, and we should understand their impact.”

Not Surrendering is at Belfast Exposed until 28 October. A book of the same name is out now