All images © May Colson

Max Colson is obsessed with spaces and how we interact within them. Here the artist and lecturer discusses how this underpins his installation photography

When Max Colson walks into an exhibition space, he is looking for sight lines. He takes in the architecture, where the light is falling, the angles and symmetry. It is a slow, meditative process. Colson also imagines himself as a visitor and walks the paths they might choose. “The architects and interior designers spend a lot of time talking with the curator over the design of the space and how people should be led through,” he explains. “You’re trying to look for those visual channels.”

As a photographer, Colson is there to document the installation in situ, so he notes any reflective surfaces and how best to use lighting to catalogue the artworks. His role is both pragmatic and creative, and he is now a regular installation photographer for galleries, institutions and museums such as the Barbican and The Showroom gallery. The works on display change, but he has built a detailed knowledge of these venues’ architecture, and insists this is essential. “You want to give a sense of the space that you wouldn’t normally be able to see if you were just walking around the exhibition,” he says.

A commission usually starts with a phone call or meeting with the curator or assistant curator, to get some understanding of the show and the themes that underpin it. Most exhibitions at the Barbican take a day or so to photograph, but new clients – many of whom want the job done quickly – often suggest desired shots. Colson will then give them a rough quote, detailing what is possible in the stipulated time.

Often his first viewing of the exhibition is when he arrives to take images, typically on the day of installation. Earlier recces are unfortunately a rarity, because budgets do not allow for it. “Occasionally there are architectural visualisations and sketch up models that I can see,” he admits.

Time is pressurised, both because there is not much of it and because the gallery is on a deadline to open to the public. Initially, Colson simply notes the practical and technical requirements. “I look for the big obstacles to capturing good photographs, such as glass cases or big paintings that are behind a glaze,” he explains. “Objects like that can take a long time to photograph, because you need to have apparatus set up to counter the reflections.”

After that, he works his way through his mental shot-list, which will include wide photographs of each area of the gallery. He systematically documents every wall then gets closer to capture the details. Colson tries to make the Barbican look as immaculate as possible and, although there are always people around when he is working, he prefers not to include them in the images. However, his other commercial career is events photography, and for that he is invariably trying to capture as many people as possible in the space. It is a perfect foil to the installation work. “Event photography is reactive and fast,” he explains. “You’re working with people who are usually in a crowd, happy and easy to work with. The editing can be a huge job, because you’re taking a lot of images to get one good image of a particular group.”

“I partially do the editing process when I’m shooting. I’ve usually got a plan for what images I need to get. You’re not chasing moments because the installation is static, and the editing process is more about refining”

By contrast, when photographing exhibitions, Colson edits as he goes along. “I partially do the editing process when I’m shooting,” he says. “I’ve usually got a plan for what images I need to get. You’re not chasing moments because the installation is static, and the editing process is more about refining and delivering pristine images – for example, removing dust.”

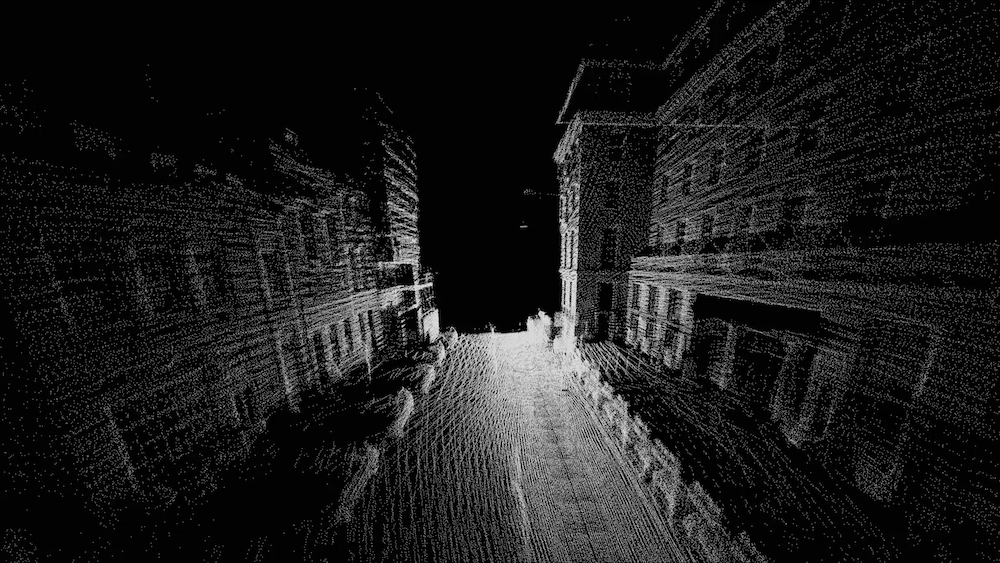

Colson also photographed the showcase of Central Saint Martins’ graphic communication design degree course, as well as “the exhibition in motion”. He is an associate lecturer at the university, and says being a practising photographer definitely helps his teaching. The university and commercial work allow him to devote time and resources to his art practice, which is also characterised by a fascination with space. “I have been using a LiDAR 3D scanner to scan London’s streets for the last five years,” he says. “I’m interested in laser scanning as an ‘expanded photographic’ technology.”

This interest has led to two projects – Offshore Capital, documenting ‘ghost’ property in London owned by offshore companies based in tax havens, and London Knowledge, a short documentary film using 3D scanning animation, journeying through the London streets black-cab drivers memorise for their ‘Knowledge’ qualification. The latter was screened in Piccadilly Circus last year; an aptly chaotic, iconic and central location.

Colson enjoys the balance, but admits it was hard to achieve. His decision to move into photography was impetuous, he says, and it took years to get a foot on the lowest rung. For those considering installation photography, he advises talking to people in the area or, better still, assisting an architectural photographer. “I never did and I wish I had,” he says. “Architectural photographers often have budgets to pay for assistants. You’ll also learn about client workflow and how to light interior spaces, and it will set your job expectations.”

Architectural photographers might also have tips on kit, as this is a specialist area in which “investing in equipment is important, and expensive”. He shoots with a Nikon D810 and a good range of lenses, including wideangle, mid-range and telephoto zooms, a wideangle architectural tilt-shift, a macro and two primes. He deems a lens belt as essential, and also takes flashguns, spare batteries, memory cards, a tripod and a laptop.

Getting started can be nerve-wracking, he adds, but it only takes a couple of curators to notice your work to give you a chance. “It was a constant scramble when I started out,” he says. “But I was all right once I got one or two people who keep on coming back.”