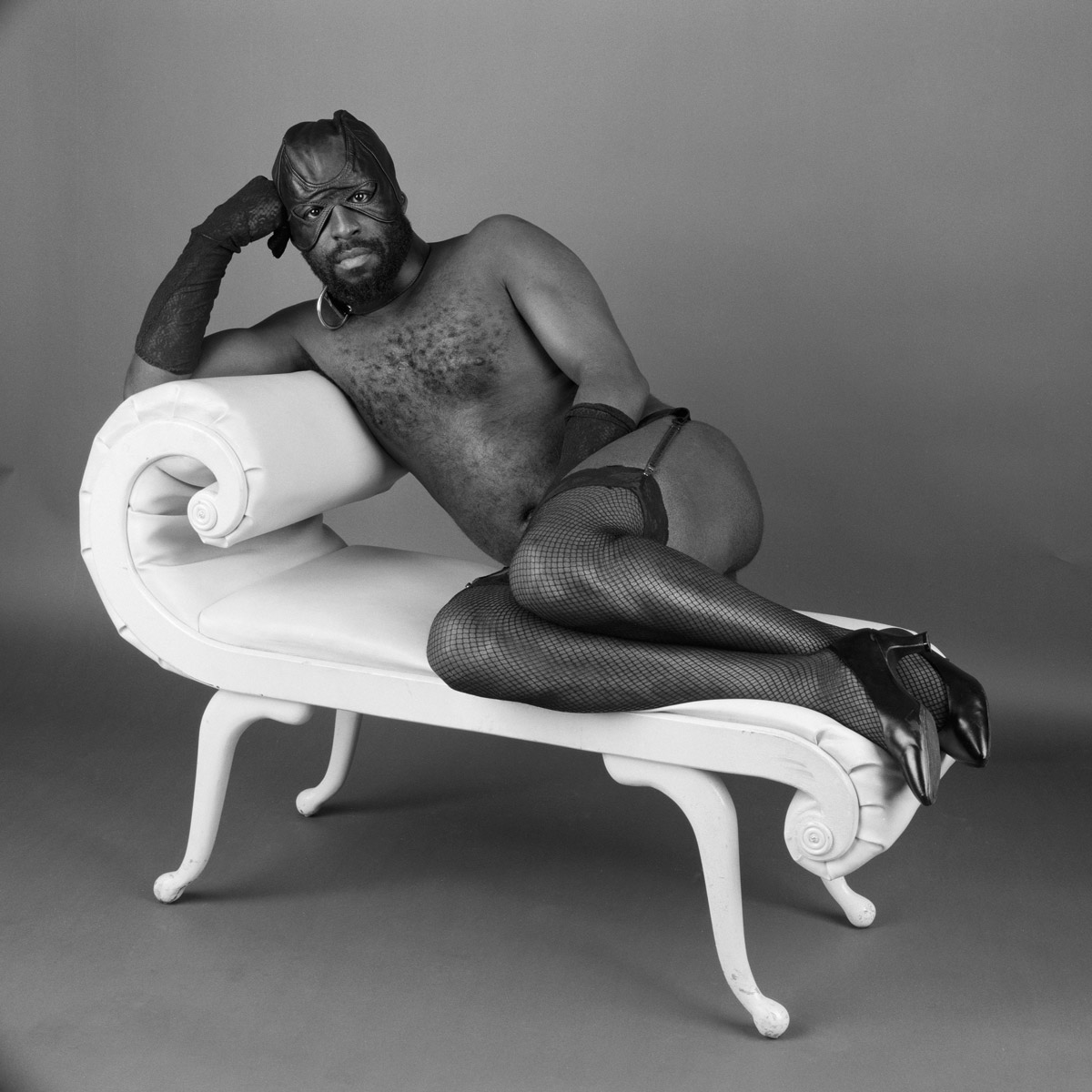

Self-Portrait on Chaise Lounge, Syracuse, 1998. All images © Ajamu X. Courtesy the artist and Autograph

As his new solo show opens at Autograph, the trailblazing photographer talks to Amelia Abraham about the eroticism of Black British life – and the endless possibilities of darkroom encounters

Ajamu X sits atop a chaise longue in stockings, suspenders and heels, legs folded demurely at his side. He wears a leather BDSM mask and gloves, a light spattering of hair dappling his chest. His Black skin juxtaposes the unnaturally bright white furniture, a contrast heightened by the neutral studio backdrop. It is a classical self-portrait, a reference to the work of E. J. Bellocq, the American photographer who captured sex workers in the early 20th century. Ajamu looks at the camera, poised yet vulnerable.

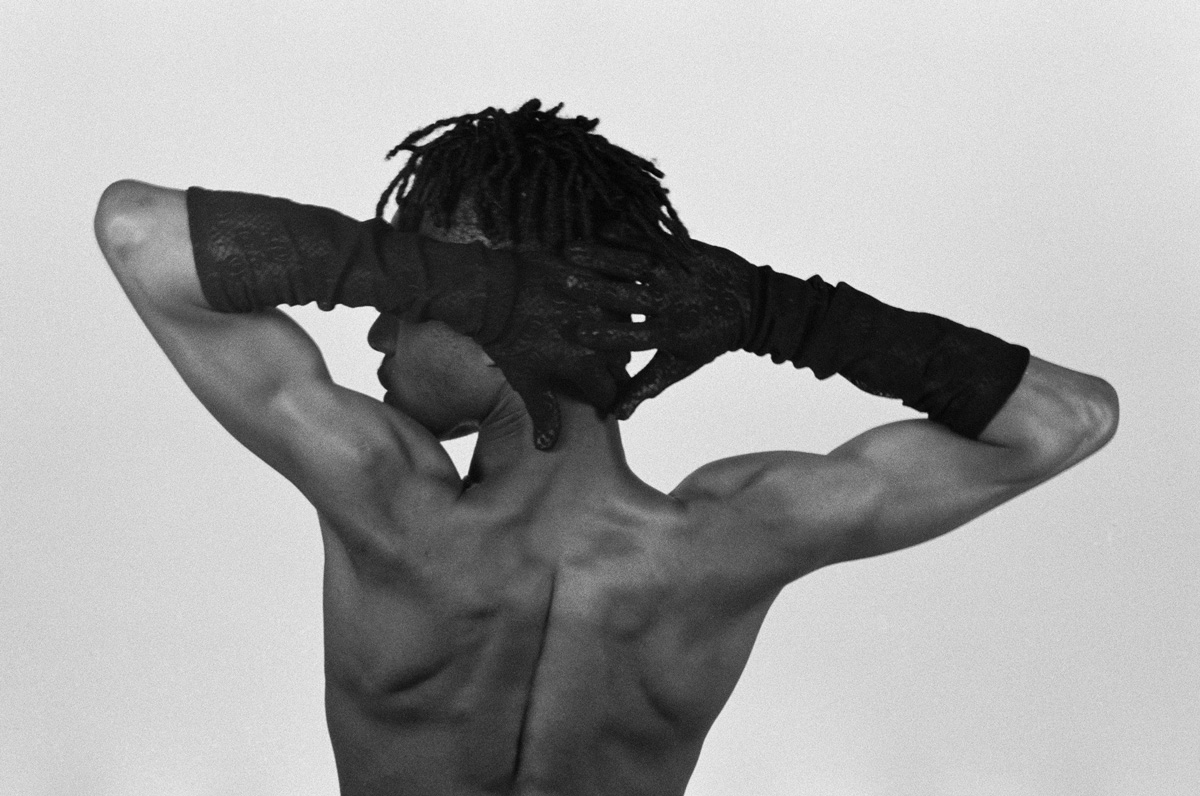

The work beckons us into The Patron Saint of Darkrooms, Ajamu’s new show at Autograph in East London. Self-Portrait on Chez Lounge sets a precedent for the show’s imperative – “to talk about aesthetics and beauty” – in the words of Ajamu, “when there has not been a history of hearing Black folks talk about beauty, of saying, ‘this is what turns me on, this is what I find beautiful.’” His subjects, often Black queer men, are captured in moments of gentle power, ecstasy or invitation.

Self-Portrait on Chez Lounge was taken in 1998, but Ajamu X began recalibrating the representation of Black queer Britain over a decade earlier. Since relocating from his hometown of Huddersfield to London in 1988, his practice has committed to archive-creation: “I want to document the whole of Black queer Britain, it’s what I call an impossible project,” he says. This drive has been described as “Pleasure Activism” – a desire to celebrate the eroticism of Black British life and to create the kind of images we rarely see. (Ajamu traces the term back to trans writer Pat Califa and the early 90s, via Adrienne Maree Brown and Audre Lorde’s The Erotic as Power). The Yoruba name he adopted in 1991, ‘Ajamu’, means ‘he who fights for what he believes in.’

Ajamu has featured in several high-profile London shows over the past five years: The Hayward Gallery’s Kiss My Genders in 2019, Fashioning Masculinities at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2022, and Very Private? at Charleston House the same year. His contact sheets are currently on display at The Photographers’ Gallery in A Hard Man Is Good To Find, an examination of male physique photography in Britain. Patron Saint is described as an “overview” – a snapshot of Ajamu’s vast body of work, and a rejection of the term ‘retrospective’. At 60 years of age, his cultural contribution is far from complete.

After this rush of institutional exposure, one might say Ajamu X has been having a ‘moment,’ but he rejects the label. “I push up against this idea of a ‘moment’ – a lot of us have had long moments,” he says. “Some spaces are catching up because ideas have shifted, or the work has entered these spaces primarily because younger queer curators are trying to make them diverse and inclusive.”

“I’m a sexual being without apologising for being a sexual being… Lots of us might be out around our sexual identities but marginalised around our sexual behaviours”

While there may be a spate of younger photographers shooting Black queer people today – Ajamu name checks Burnice Mulenga, Cameron Ogbodu, Campbell Addy, Alexander Ikhide, and Matthew Arthur Williams – his work stands out for its unapologetic eroticism. The mainstreaming of queer culture and pornography has made the visual language of sexuality more visible; when he began working, societal homophobia and stigma around HIV/AIDS led to censorship of same-sex male erotica.

Today, we live in a culture where erect penises are shared freely on Grindr and kink imagery is disseminated over platforms like the kink-friendly dating app Feeld. “I think that some of the work from the 90s, if we fast forward 20, 30 years, are not as intense as they felt then,” Ajamu says. “It’s a different context for the work now because the conversation has shifted. But we still don’t see Black and kink and that’s the difference.”

The show’s title, The Patron Saint of Darkrooms, is a play on the photographer’s darkroom, but also the darkroom as a cruising space – a dimly lit room one might find in the back of a gay bar or club where men can seek sex, usually with strangers. For Ajamu, there are similarities between the two: the smell of chemicals (used to develop, or in sex dark rooms to clean the space), the red lighting, and the sense of anticipation – the reveal of the image as it develops, the possibility of an encounter. “Both types of darkroom are utopian spaces,” Ajamu says. “Especially the sex darkroom because people feel liberated to explore their sexuality and pleasure.” Patron Saint is intended to stimulate viewers beyond the visual realm, whether through scent, arousal or memory.

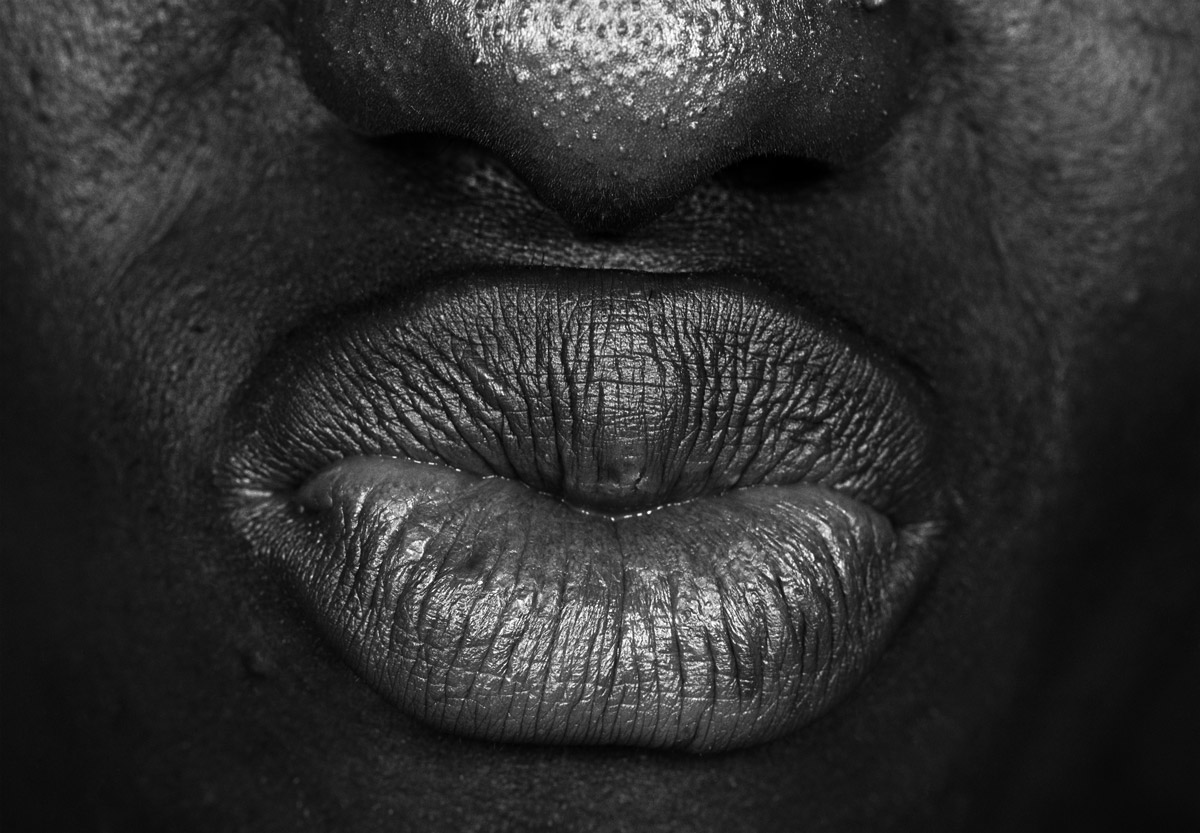

Ajamu’s work is often reduced to conversations around representation rather than form, diminishing his technical processes. “Photography around the Black body has been locked into what I call the trap of representation – this idea that if the photographer is racialised as Black and the work is queer the work is about identity politics,” he explains. “The sociocultural lens can be quite limited, as though the work is only there to do some kind of educational work. “What’s missing is discussions around process, materiality, and craft – I am more excited by the production, the lighting, and the composition.”

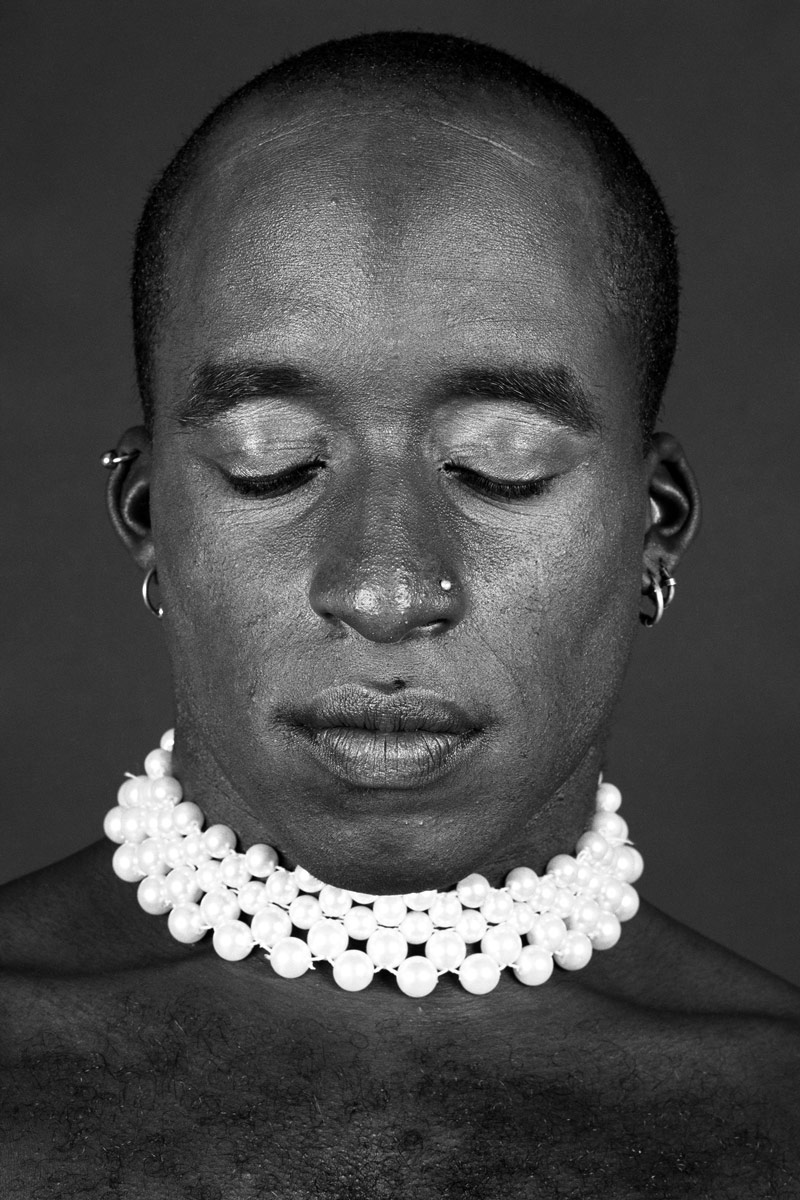

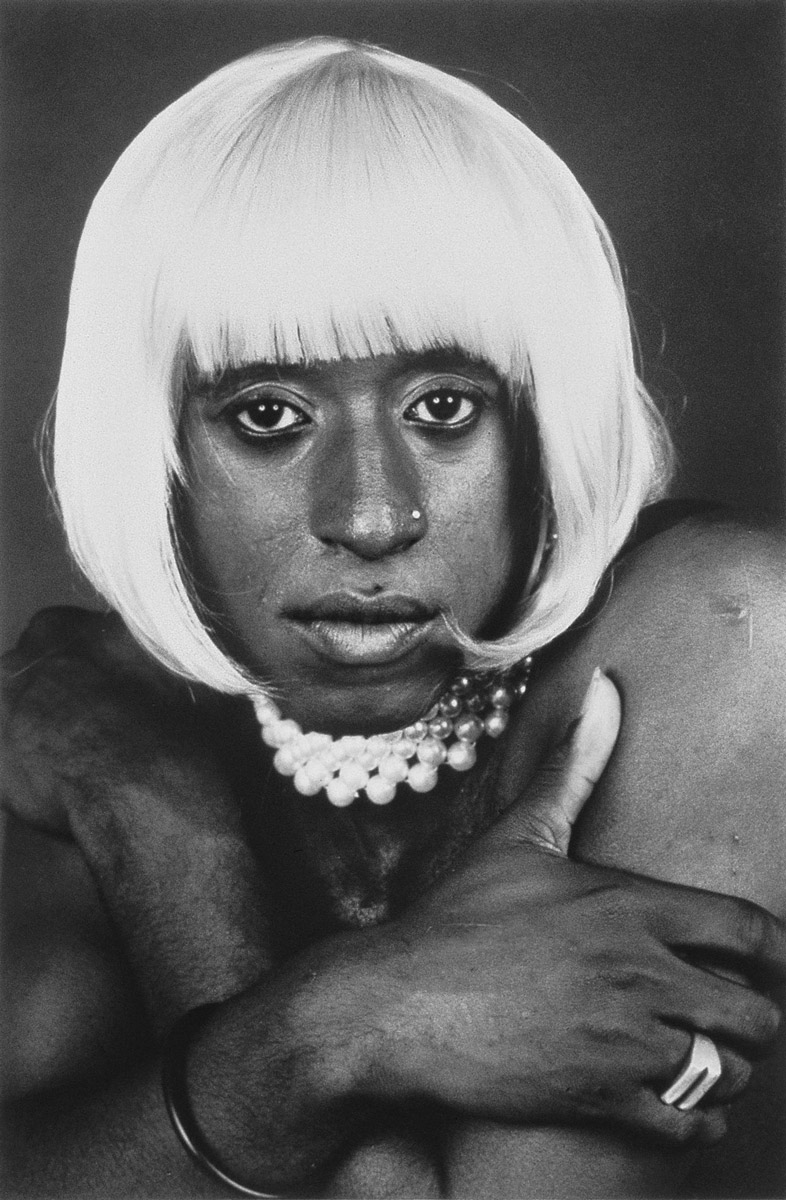

Take Ecce Homo (2023), Patron Saint’s portraits of young Black trans men. The images are platinum prints, a labour-intensive process originating in the 1870s which creates softer images. “Images we see around Black bodies often conjure an idea of violence. I wanted to create work that’s more gentle, where the tones represent how we can talk about identity in more nuanced and intimate ways,” Ajamu explains. The small prints draw the viewer in, creating “a-one-to-one relationship” through form, while the bodies in Ecce Homo are angled left or right, their head turned towards the camera. The poses reference to the tradition of photography of kings and queens who “rarely look full frontal, usually slightly aloof,” Ajamu says. His subjects appear regal, even saintly.

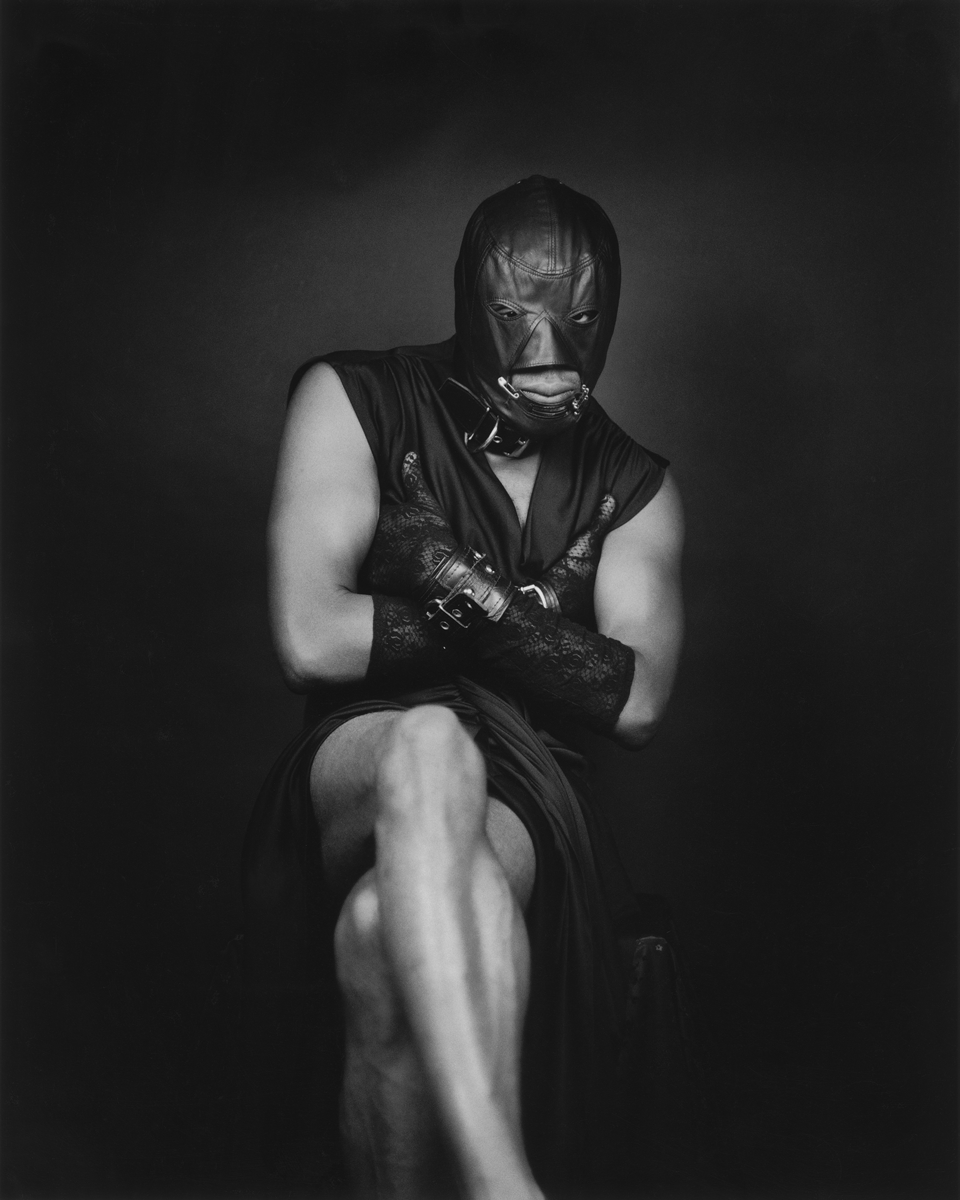

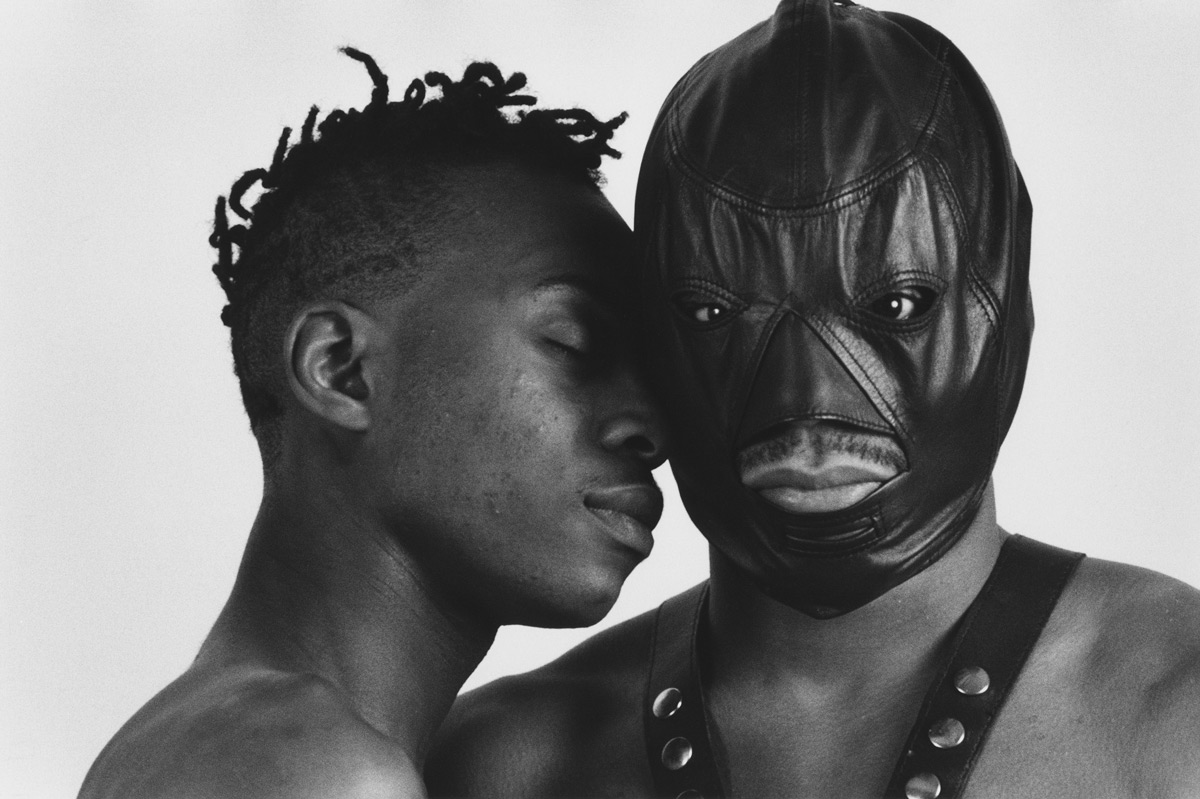

Black Circus Master (1997) features a series of images in a BDSM setting. Just as there can be a violence to the image of the Black queer body, so too can there be a violence around representations of S&M and kink. These images are intimate and sensual, capturing the “tender side” of kink that Ajamu himself has experienced. In a context where, as Ajamu puts it, the more that LGBTQ+ history mainstreams itself the more it becomes palatable or sanitised, these images may, to some, feel challenging.

“I think we still live in a culture that’s erotophobic, so there’s a reluctance to show particular types of work,” he says. “But because I’ve come out of a post-punk moment, historically, the attitude is very ‘fuck you’. For me it’s about: how do we confidently and openly talk about what turns us on – and how that is political?”

This is the crux of Ajamu’s Pleasure Activism. “I’m a sexual being without apologising for being a sexual being,” he declares. “Lots of us might be out around our sexual identities but marginalised around our sexual behaviours.” Patron Saint aims to bring us back to the agency of the Black body for this reason. “We spend a lot of time talking about what is done to Black and Brown bodies – and we should not lose sight of that – but at the same time what do we want to be done through and with these bodies,” Ajamu explains. “We still love, we still fuck, we still sweat, why are we not talking about that bit?”

Ajamu X, The Patron Saint of Darkrooms, is at Autograph, London, until 02 September