© Mateo Arciniegas Huertas

Working through the trauma of the asylum seeking process in the US, the photographer says he came to photography later than his peers and uses it as a mechanism to heal intergenerational migratory disruptions

Mateo Arciniegas Huertas moved to the United States with his mother in 2010, and wasn’t able to travel back home to his native Colombia for seven years while they waited for their green cards. Huertas was able to apply for citizenship through the asylum process, but just weeks after he received his passport, President Donald Trump took office. Huertas felt compelled to travel back to Colombia immediately afterwards.

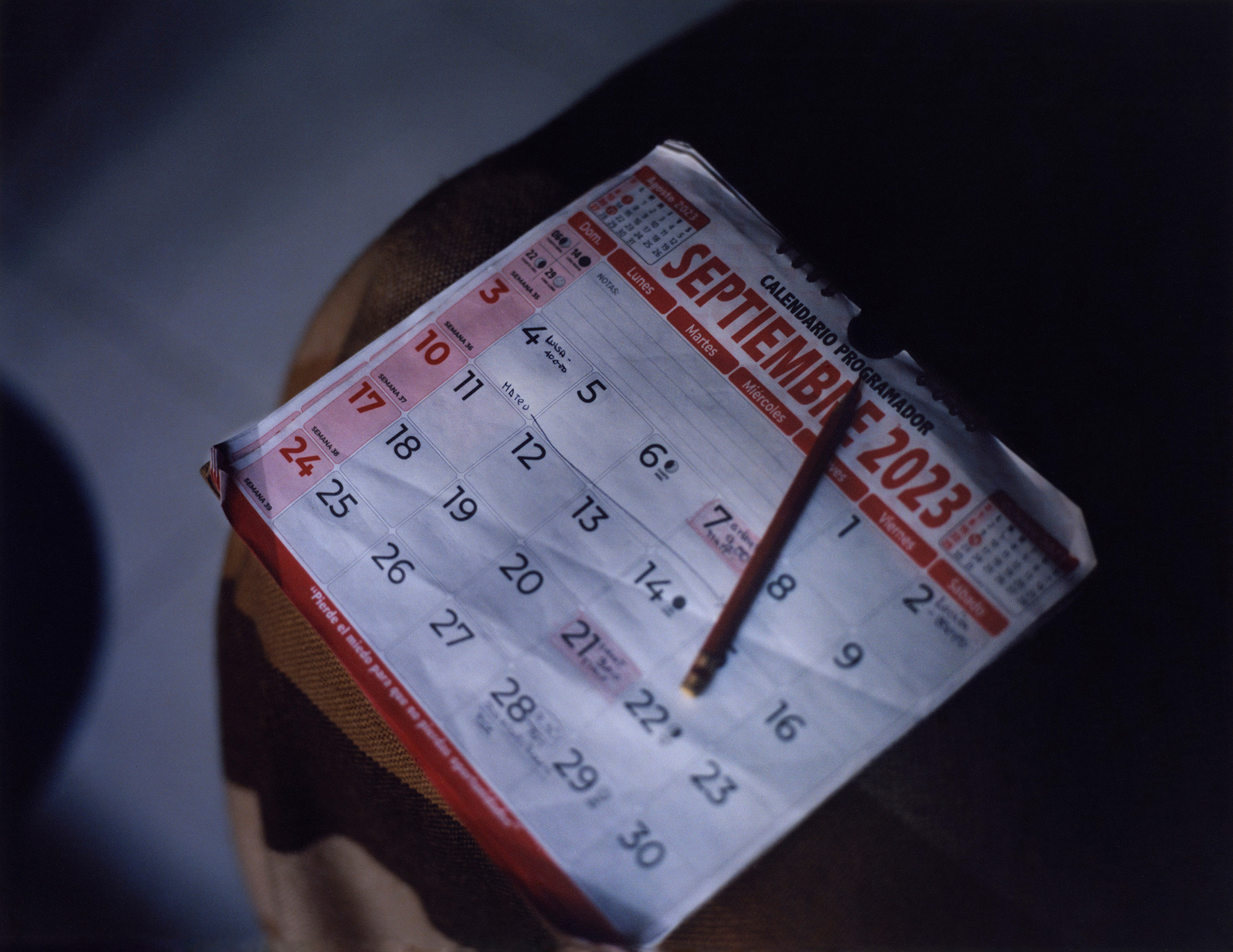

Though he had attempting to get into photography from a young age, after his mother enrolled him in a class in Bogota, Huertas’s migration to the states disrupted his progress, especially as he felt he needed to focus on financially stable work. He eventually picked up photography as a trade after moving to New York City, while attending community college, where he started “to get my first [experience] within photography that could exist outside of making money or a survival tool, which was what it was for me for many years,” he tells me. This is also where Huertas began shaping an ongoing family-focused project in Colombia, which he had shot over seven years, before transferring to Pratt in Brooklyn to finish his studies.

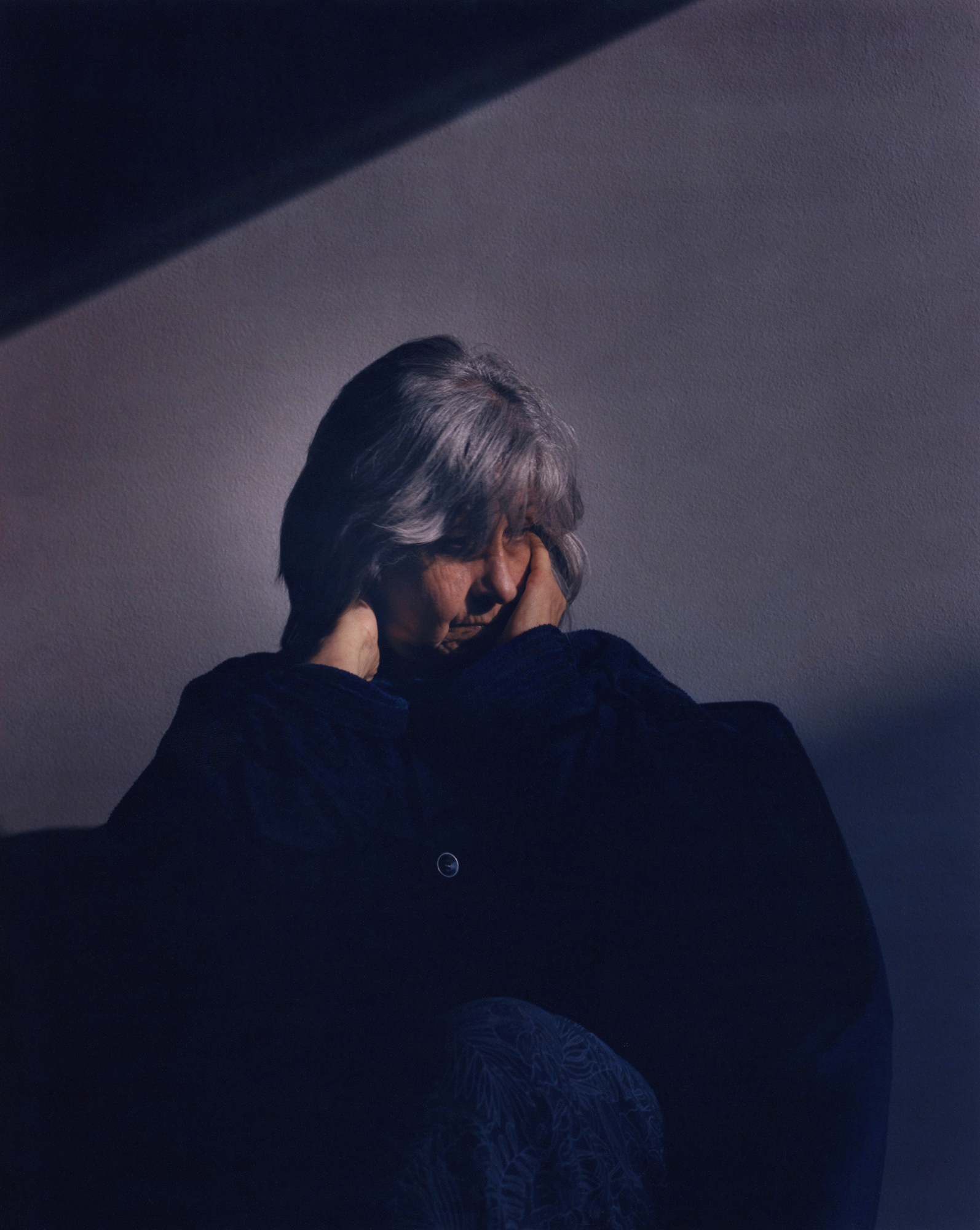

Olvido pa’ Recordar (Forget to Remember) is a reconstruction effort of sorts. The series follows mostly the women of Huertas’s family, who largely raised him, and “stems from my story and myself and then, as a projection of what’s around me,” Huertas tells me. “It’s my archive of loss, but at the same time, because there’s a certain solitude that I feel when I’m there [in Colombia], but I also feel when I’m here [in New York], it’s building an archive not only of my family but also of that feeling of alienation that I’m perpetually feeling no matter where I go.”

“It’s building an archive not only of my family but also of that feeling of alienation that I’m perpetually feeling no matter where I go”

The series is an attempt at letting go. Huertas grew up in a Colombia which has now become unrecognisable to him. Violence in the country is slowly quelling, and areas of Colombia once inaccessible are opening up; family members have died since he left, now living only in his memory, and his childhood friends have grown apart. Huertas has to learn to forget what he once knew, a painful grief experienced by many migrants forced to leave their homelands.

The series is steadily quiet and still – domestic spaces and objects are observed, and Huertas’ subjects are often seen from a distance. We are carefully finding ourselves in the homes and in the landscapes of Olvido pa’ Recordar. In 2016 the peace treaty with FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia–People’s Army) was signed and the photographer claims there was a new hope in the country and a new opportunity to travel around it. “So, it was a process of discovering the unknown within my country because in the time I grew up, the interest in travelling around Colombia didn’t exist,” says Huertas, reflecting the hesitance felt throughout the series.

“But then, what quickly became the project was realising that things just change. Family members have died, people don’t hang out with the same people they used to, the country has changed… So I’m trying to slowly get through this therapeutic process and understanding of a loss, like a mourning of my life when I was growing up,” he continues.

Navigating a migrant experience made adjusting to life in the US a struggle for Huertas; he tells me that he has no childhood memories, bar three or four, which has meant that “the idea of memory is very important” to him. “Sometimes I go to places and I talk to my mum [about it], and she helps me remember things or points out things from my family’s past.” The project thus combines Huertas’ material with trying to capture the aesthetic manifestation of oral archives.

In one particularly tender moment in Olvido pa’ Recordar, Huertas captures his aunt Gloria, who passed away three years ago, celebrating her birthday and blowing out candles. Gloria was a nun – unmarried and without children – through the late 1950s until the 80s. “She went to Italy by boat and came back and then she quit being a nun,” he says, though she remained committed to her faith until her death. The image was shot in December 2017, during Huertas’ first time going back for her birthday since he had left as a child.

One of Huertas’ very few memories is his crush on a classmate when he was about six years old. “I told her about [my crush] and then she told me to buy her flowers… So [I] went over to her parents and to the girl, and I just gave her this [bouquet] of flowers.” Huertas has a special connection to flowers, which he finds especially expressive; in many Latin American countries, marigolds or ‘kalendula’ are also used as remedies for burns and minor injuries. The flower “becomes like this cream that you can apply on a wound to help it heal”, he says, an appealing metaphor particularly when combined with his image of marigolds shining in the golden-hour glow of sunset.

“I grew up in a matriarchal family… I was always around women, my aunts, my mum,” Huertas reminisces, in reference to another portrait showing his aunt Betsy. “The women were and are always more important in my life than the men.” Olvido pa’ Recordar is marked by maternal lineages, the lens almost always dominated by women or girls.

It contrasts Huertas’ series Madison, which captures migrant Latin American men who play community football in Brooklyn. Huertas met the group during the pandemic and says that the camaraderie between the men was immensely soothing during a time in which he felt a distinct lack of community, particularly as a migrant. But this work has since taken on new resonance, after Trump’s re-election.

“Now that Trump has won a second term, there’s things that I do want to say and I want to be political about it without being cliche,” he says. “My work itself and my story has a political tone to it. And I cannot hide that and I don’t want to hide that. Because of the fact that I’m a result of an asylum seeking process, and I’m very grateful for that.”