Shannon. Thursday 4 April 1996. Southerly 6 to gale 8, decreasing 4 in northwest. Occasional rain. Moderate or good.

The Magnum photographer talks to Ravi Ghosh about reissuing The Shipping Forecast, his seminal book navigating the British Isles’ 31 sea areas

Mark Power sits in his Brighton studio, trying in vain to think of today’s mass cultural rituals. TV shows, behaviours, or events that bind the UK together – not necessarily in fandom or intrigue – but by their sheer omnipresence and historical weight. Power recalls the collective excitement when Twin Peaks first aired in the early-1990s. However, we eventually conclude that the nation is currently lacking in any such customs, except perhaps those surrounding international football.

Certainly nothing now holds the place that the Shipping Forecast did throughout the 20th century. The gentle, often unintelligible weather news from the 31 sea areas around the British Isles, wafted into living rooms via the BBC Home Service (and later Radio 4). It is still broadcast four times a day, though it now jostles for space with every other type of content imaginable. It’s worth tuning in, just for its oddity. Take the forecast for Friday 13 January 2023, the day I visit Power: “Low Hebridies, 974, expected North of Denmark, 985 by 1800 Friday… Viking, North Utsira, South Utsira, cyclonic, four-to-six, increasing seven at times, showers: squally at times, good, occasionally poor.”

“It’s a beautiful, poetic language,” Power says. Now 63, the Magnum photographer first remembers listening to the forecast growing up on a housing estate in Leicester. The soundscapes had a lasting impact on Power, whose father spent his two years’ national service in the merchant navy. Years later, while visiting his brother near Great Yarmouth, the photographer bought a tea towel showing a map of the sea areas, and realised that he had developed mental images to correspond with the forecast’s audio fragments. The mind’s eye rumbling slowly in the background, fed for years on a diet of gale warnings and area forecasts (and ship icing, if you’re lucky).

“The mention of any sea area – say, Rockall – immediately brought to mind an image which had been gestating since childhood,” Power recalls. At the end of 1992, he began making images of Wight, the shipping area off the coast of his hometown, Brighton. Over the next few years, he would travel to all 31 zones by campervan, a Mamiya 6 Rangefinder in hand. The Shipping Forecast, Power’s first major project, was born.

“I’m trying to make visual metaphors that don’t in themselves make sense. Pictures that withhold information, and are therefore mysterious”

The book, first published in 1996, has now been expanded and republished, with 103 extra photographs offering new coastal perspectives from Lisbon to Skegness; Barry Island to Biarritz. The original volume was a commercial and critical success, selling 10,000 copies in three runs, including to a non-photography audience. First editions often now crop up in Oxfam bookshops, Power says, the result of children clearing out their parents’ houses and finding a single, somewhat nonsensical photobook tucked among the bric-à-brac.

Power is aware that today’s cultural environment – and audience – has shifted from that of the mid-1990s. The nostalgic association for the Shipping Forecast has diminished, meaning interested parties are now recast as eccentrics. Without a contemporary comparison, it’s difficult to explain that it was just part of everyday life, a “wallpaper backdrop,” Power says. “I wanted to do the project from the point of view of the lay listener. The ‘landlubber.’” He bristles slightly while recalling a recent radio interview where he was asked whether he loves the forecast. “I don’t,” he tells me bluntly. “I’m just like everybody else.” But today’s ‘everybody else’ isn’t the same as yesterday’s.

This affinity with the “accidental listener” made Power focus closely on the ocean itself. In selecting no more than three photographs from each sea area for the original book, he distilled thousands of mental images, codifying a fluid national consciousness into firm visual facts: what each of these places actually looks like.

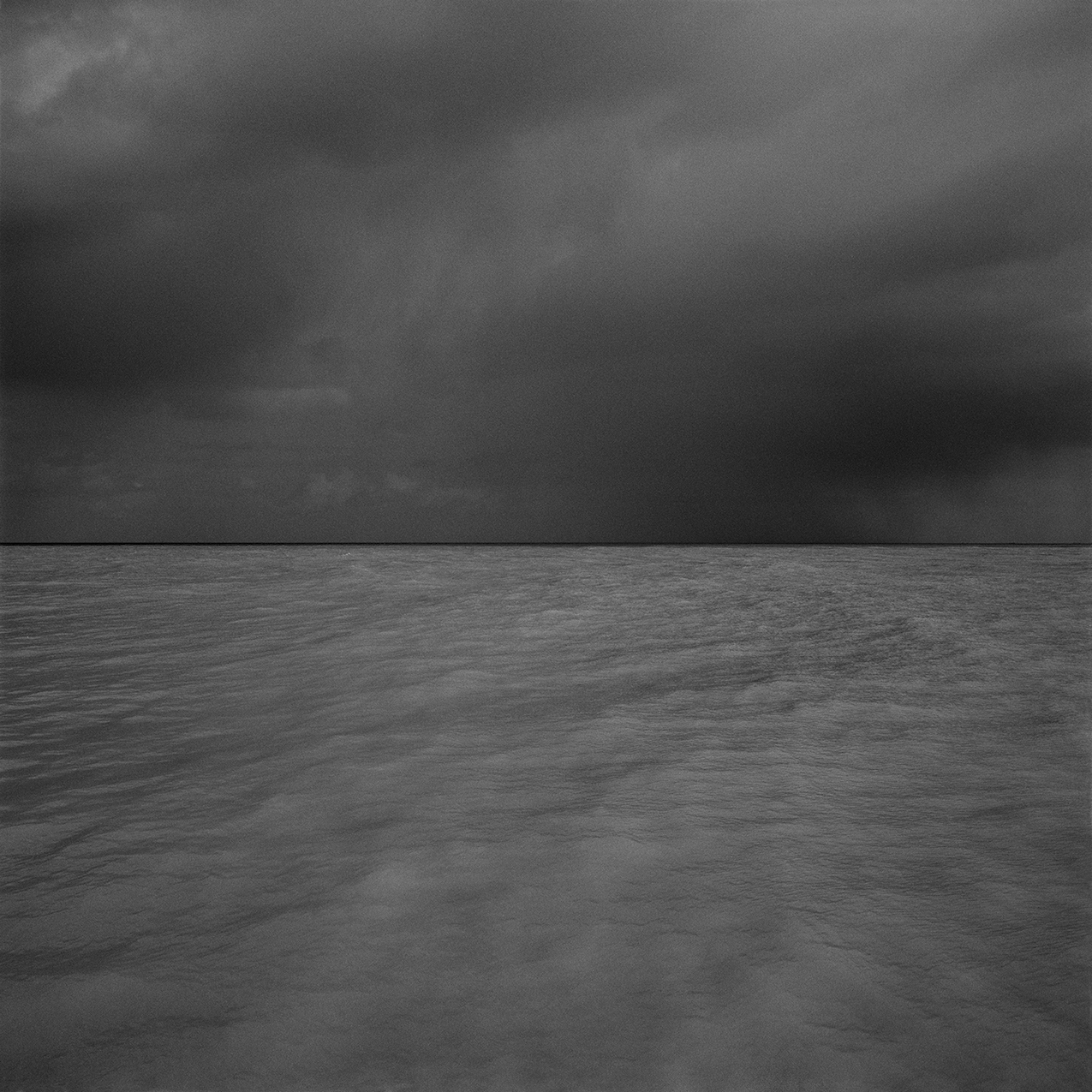

The new edition opens with a photograph of the sea at Wight, the water stretching towards the horizon like polished slate. More often than not, the landscapes are flat and the sea calm. Mourners gather at a hilltop cemetery on the coast of Shannon, Ireland, the water endless below them. Steam rises from a modest bay in Iceland while boys play with a plastic chair in the shallows. The black-and-white format emphasises the sand’s indentations, tide lines and footprints complementing the liquid textures.

The horizontal lines of the seas and promenades often split Power’s compositions, framing objects in the foreground. At Herne Bay, a kiosk sits perfectly in the centre of the 6×6 shot, a focal point on an empty walkway. At Deal in Dover, wooden benches are rooted in perpendicular conference, hard and firm with the sea fuzzy behind them. The shots anticipate Power’s work made travelling around the US, a quieter, more typological approach to topic and form. The subject matter in The Shipping Forecast is “vague and abstract, which suits the language of photography,” Power says. “I’m trying to make visual metaphors that don’t in themselves make sense,” he adds. “Pictures which are, in their own way, difficult to understand, that withhold information, and are therefore mysterious.”

“The book doesn’t take us any closer to an understanding of the forecast, or any sea area. But it is nostalgic and unashamedly romantic”

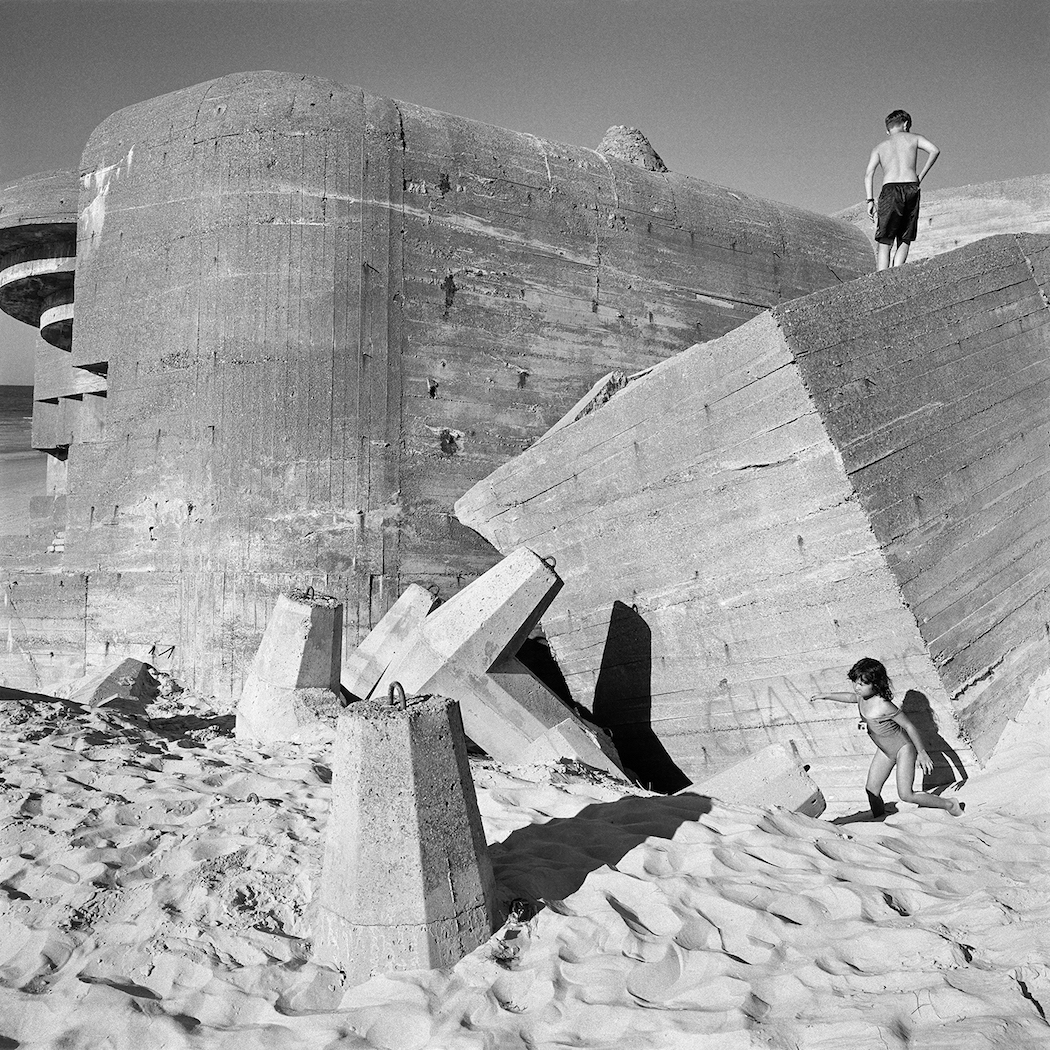

Onshore, there is more drama. Men watch bathers in the Porthcawl beach swells, while another erects a windbreak as the waves clamber and crawl in the background. This kind of British coastal photography prompts a widespread response from readers, Power explains. “It taps into people’s own childhood memories of beach holidays with their families.” In particular, lots of observers fixate on a photograph made in Scarborough of a young girl riding a donkey under gathering black clouds.

The image’s atmosphere is familiar: the stasis and claustrophobia of British summer. Arcades, high winds, sunshine and showers. Sometimes the Shipping Forecast texts beneath each image seem to match the photograph above; or at least, we project that they do. A pair of walkers battle the wind with hoods up on Utah Beach, Normandy. “Rain then showers. Moderate becoming good” suggests better weather ahead.

The Shipping Forecast stands slightly apart from the British social documentary tradition, mainly because of the creative and logistical choices Power made while shooting. He did little research before travelling and spent no extended periods of time with his subjects, sometimes stopping off for just 20 minutes.

Tony Ray-Jones and Chris Killip are touchpoints, but where their work seeks to explore a specific social condition, Power’s is non-prescriptive. Between 1985 and 1987, he shot on commission for the Children’s Society to lay bare child poverty in the UK, but The Shipping Forecast feels mostly unpolitical – roving and incidental. These days, Power doesn’t see much value in working in a ‘story’ or editorial format. The book “doesn’t take us any closer to an understanding of the forecast, or any sea area,” he explains. “But it is nostalgic and unashamedly romantic.”

Does this mean there is nothing of Power’s personality in the work? That anyone, armed with a map, campervan and camera, could have made The Shipping Forecast? The more we talk, the more his hand and vision become detectable in the project, despite the structure underpinning it.

Power was a keen competitive dinghy sailor up until his children were born, and he makes no secret of his love for the sea. There are also psychic traces in the work too, recurring characters and dynamics. Parents resting while children play around them; hilltop walkers; quiet rather than active companionship. Even a note of melancholy. Power says that he was often lonely as a child, perhaps explaining the motif of solitary children in the book. When people peer off a cliff into the distance, they seem on the precipice, actors in scenes of near-existentialism. We don’t know what they’re thinking, and neither does Power. That this doesn’t bother him is refreshing, a licence for reader speculation and daydreaming.

Twenty-six years on, Power still explains the project in abstract terms. “When I arrived in a place I’d not visited before, the imaginary landscape I carried with me would quickly disappear,” he says. “The clash between that, the imagination and the fiction, was quickly replaced by reality and fact. Where the two meet is where the best pictures came from.”

The air of mystery is intentional. He writes in the new book that documentary photography “becomes more interesting (or, at the very least, different) with the passing of time.” Old friends and readers linger or forget, new ones take time to enter into the world of the images, to form their own associations. Like the sea, definitive meaning is out of reach – that’s what keeps people coming back. “I’m trying to make pictures which don’t explain themselves,” Power concludes. “And that are hopefully also beautiful, because the language of the forecast is also beautiful.”