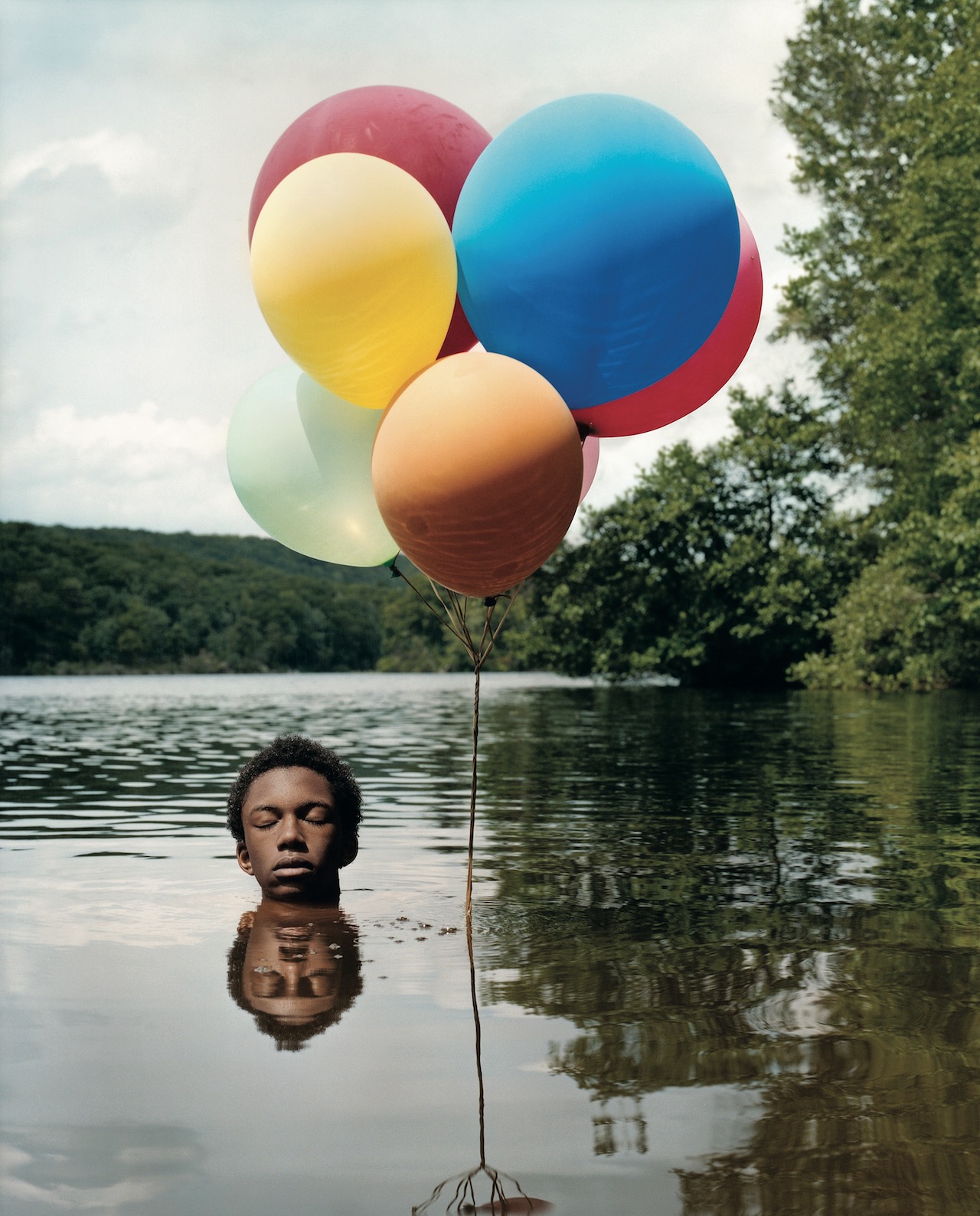

Chrysalis, 2022 © Tyler Mitchell.

As his first solo show in London opens this week, the 27-year-old artist reflects on the explosive trajectory of his career, and ambitions that extend beyond the parameters of photography

It is a picture of peace. Eyes closed. Shoulders down. Relaxed brow. The young male figure rests his head on his folded arm, softly cushioning it as young infants do in the days immediately after their birth. A mosquito net, sheer and fragile, drapes around him, creating a womb-like shelter. Beneath him the perfectly imperfect creases of a floral bedspread offer comfort. Illuminated in a cinematic halo, the figure lies in a classic repose. He is the idealised vision of rest. We watch him sleep.

Like much of Tyler Mitchell’s new work, Chrysalis asks more questions than it answers. There is a suspension of time – an intentional slowness. Mitchell is forcing us to ask questions about our location. Is this a painting? Is it a film still? Where are we within the history of image-making? The series continues to build upon the American photographer’s fascination with landscape and what it means historically and contemporarily for the Black body. What is new is that Mitchell is reaching for a more spiritual place. He is thinking about the landscape of the body, the mind and dreams, and how interiority can make way for new imaginings and more profound emotional entanglements.

Chrysalis [above] is a photograph and the title of Mitchell’s latest exhibition, which goes on display at London’s Gagosian gallery on 06 October. Curated by his long-term collaborator Antwaun Sargent, the show is a defining moment for the 27-year-old. It will be his first at the renowned gallery and his first solo show in London – a city that holds much resonance in his formation as an artist, and where he shot covers for Dazed and I-D magazine. It is also home to personal projects such as Boys of Walthamstow (2018).

The exhibition marks a new era in Mitchell’s practice. The utopian vision of Black life in nature that we have come to know him for is interrupted by something haunting and more complex. His visual language has evolved, and his approach refined. Yet Chrysalis is more than a deepening of practice. It marks a moment of reckoning with the institution – a refusal to conform. “The first thing racing through my mind when I was invited to make the show was that I didn’t want to make it easy for people,“ Mitchell says. “I wanted to make a body of work intentionally complicated and intimate, something that could bend time and be difficult to place. My whole project as an artist is to blend these boundaries of commissioned and personal work, conceptual and narrative work, and figurative and abstract work. I wanted to find my own world in the midst of all of those interests.“

“The first thing racing through my mind when I was invited to make the show was that I didn’t want to make it easy for people. I wanted to make a body of work intentionally complicated and intimate, something that could bend time and be difficult to place”

Stages of evolution

I first met Mitchell five years ago in a cafe in Shoreditch. He was 22 and a recent graduate of New York University Tisch School of the Arts, where he studied cinematography. He was on a high from shooting his first fashion campaign for Marc Jacobs – a Dipset-inspired series of young men in womenswear – that centred on friendship and boyish innocence. At the time, Mitchell was working hard to make a name for himself, shooting editorials and making videos for musicians like Abra and Kevin Abstract. There was a buzz about his first book, El Paquete, where he documented Cuba’s emerging skate scene in the summer of 2015. Even though his lauded US Vogue cover of Beyoncé, for the September 2018 issue, was still a year away, Mitchell had quickly established the concerns of his practice and was making images that felt uniquely his.

Today, Mitchell’s work is a portal for Black utopia. A space for young men, in particular, to revel in beauty, desire, empowerment, play and self-assertion. In his show, I Can Make You Feel Good, first presented at Foam Amsterdam in 2019 and later at the International Center of Photography in New York, we see young people flying kites, holding balloons, hula-hooping and picnicking. The show was a declaration – described by Mitchell as “gut-punching in its optimism” – that offered a new visuality of Black youth rooted in joy and liberation.

In Chrysalis, the artist charts new terrain. Mitchell diverts his focus to the extreme contrasts of the American Dream – not only between the seductive aspiration and ongoing threat, but also in the violent history imprinted onto the landscape and psyche. His portraits, such as Treading [above, left], in which a boy’s head sits on the lake next to colourful balloons, or A Glint of Possibility [above, right], where the same boy is suspended in equilibrium on a tyre swing, speak to survival and resilience.

“As Black folks, we constantly have this relationship to water that can be spiritually beautiful and restorative while also carrying the connotations of struggle in how we passed through the transatlantic slave trade”

And yet, the images solicit a quiet fragility, a foreboding sense that the peace could be interrupted at any moment. This sense of unease becomes more pronounced in Cage [top image, and cover of the upcoming issue of British Journal of Photography] It depicts an image of a woman lying down relaxing, set against a painted backdrop of a garden surrounded by a white picket fence. Cage embodies many of the qualities that make the exhibition so radical.

Aesthetically it straddles fashion and art, playing with notions of performance and the constructed landscape – but its intrigue resides in Mitchell’s manipulation of time. The image moves back and forth through history, forcing the viewer into a limbo state, left to inhabit feelings of confusion and discomfort while simultaneously marvelling at the expression of beauty and grace. While the exhibition might be a story of emergence, Cage is a provocation – one that feels inherently autobiographical, an insistence by Mitchell that his practice will not be tamed.

Water and mud are a persistent presence in the exhibition. Informed by the materiality of Haitian voodoo rituals and Christian baptisms, the elements dominate in images like The Heart and Distillation [both below], codifying notions of spirituality and transformation. “I kept coming back to the power of water,” says Mitchell. “As Black folks, we constantly have this relationship to water that can be spiritually beautiful and restorative while also carrying the connotations of struggle in how we passed through the transatlantic slave trade. I was struck by the beauty of swimming through mud. It’s a struggle and eerie, but it also has so much radiance and beauty. I’m interested in these allusions of freedom and transcendence.”

“As photographers, we always have so much to prove – first and foremost, to ourselves. That we are not just guns for hire or documentarians of a moment – but we are creating and shaping culture through images. I’m led by my love to make. Above all else, my calling is to the work”

Mitchell acknowledges that he is now reaching for the psychological space. “I’m referencing the ways that we are spiritually or aspirationally tied to the land. The way the land – Southern land, American land, the land of the Global South – feeds the spirit while also requiring the need to be hyper-vigilant.” He continues to place importance on social politics, saying: “Certain promises have not been upheld. Systemically, whether that’s the freedom for Black people to safely move through and inhabit land, which has still been a contentious issue, or whether we think about voting rights, gerrymandering, redlining and gentrification.”

Artistic lineage and making work that sits in dialogue with artists past and present has always been a priority for Mitchell. The precedent for Chrysalis is a constellation of minds, including Toni Morrison’s novel Song of Solomon, Julie Dash’s film Daughters of the Dust, the work of Carrie Mae Weems, Hugh Hayden, Eric Mack and Arthur Jafa. Perhaps the most formative is Gordon Parks. Mitchell directly engages with the artist’s legacy in Simply Fragile, an image that echoes Parks’ Boy with June Bug (1963), made for Life magazine for a photo essay called How it Feels to Be Black. Mitchell sees the image as a way to “carry forward the torch” of Parks’ concerns, and with 60 years in between the images, it is an urgent reminder of the social justice work that still needs to be done.

Ruthlessly prolific

It is immediately clear from my recent conversation with Mitchell that his relentless commitment to growth has not wavered. Despite his explosive trajectory, there is no sense of slowing down or sitting back. Instead, he is focused on mapping an expansive practice and thinking how that might evolve. “I’m interested in being ruthlessly prolific,” he laughs. It sounds dramatic, but he means it. “As photographers, we always have so much to prove – first and foremost, to ourselves. That we are not just guns for hire or documentarians of a moment – but we are creating and shaping culture through images. I’m led by my love to make. Above all else, my calling is to the work.”

Part of this calling is to build a social practice. When I ask Mitchell about the friction points in his work, he explains: “I look up to people like Wolfgang Tillmans, Deana Lawson and Theaster Gates. I see these people as artists who are creating not only great work but also cultures around their work.” Visiting Gates’ community spaces in Chicago was a turning point for Mitchell. “He’s built a Black cinema, educational programmes, outdoor space for people to gather and created a home for Black artistic production, including the archives of Frankie Knuckles and Ebony and Jet [magazines]. My friction point is, how do I get to that place? How do I build my version of what that is?”

This grand ambition does not feel out of reach for Mitchell when you consider the ongoing success of his first curatorial project, Night at the Cinema. Originally part of the exhibition programming at ICP, the evening designed by Mitchell, constellating the worlds of film, fashion, music and art, was cancelled due to the Covid-19 lockdown. Refusing to give up and knowing his audience was probably desperately in need of inspiration, he pivoted and, along with a developer friend, built a website in two days and hosted the 24-hour event virtually from home. Screening iconic films such as Paris, Texas (1984) and Boogie Nights (1997), alongside music videos, student films and in-depth conversations with artists like Arthur Jafa, the endeavour cemented Mitchell as a polymathic creator.

Gathering momentum

Historically, it has been popular to argue that the path to success for a photographer is to do one thing well and stay in that lane. Never content with just one offering, Mitchell’s visit to London this month shows his desire to “cover as much ground as possible” and “ensure there is never a one-dimensional conversation” about what he is doing. Alongside the Gagosian show, he will present the fifth instalment of Night at the Cinema at the V&A, reveal a new commission at Frieze Masters, and be included in the New Black Vanguard exhibition that opens at the Saatchi Gallery as part of its ongoing tour by Aperture.

And yet, despite all the work and landmark firsts, Mitchell is only five years into his career. “I think a key point to grapple with is that he is still an emerging photographer,” says Antwaun Sargent, director at the Gagosian and author of The New Black Vanguard. “The art world is notoriously insular, and many people don’t know who he is. With that comes grace and a level of trying to make sure this young artist – who is hugely successful in other ways, ways that the art world doesn’t always appreciate, working in a medium that the art world disregarded for so long proclaiming it has no value – that we give him time to grow.”

From the outside, Mitchell may look like an overnight success, but he is still battling long-established modes of exclusion. It is also important to remember that his journey is not just down to a relentless work ethic and visionary strategy – he also stands on the shoulders of generations of Black artists like James Van Der Zee and Gordon Parks. They worked tirelessly for decades for this moment to come to fruition. Breaking into the art establishment is never easy, especially as a young Black man in an overwhelmingly white system. While the significance of this moment is not lost on him, Mitchell makes it clear with Chrysalis that he is not going to come quietly. And that this show is a gesture to other young artists to rewrite the rules and imagine their own futures.

Chrysalis is on show at Gagosian, Davies Street, London, from 06 October until 12 November 2022.

The New Black Vanguard opens at the Saatchi Gallery, London, on 28 October 2022.