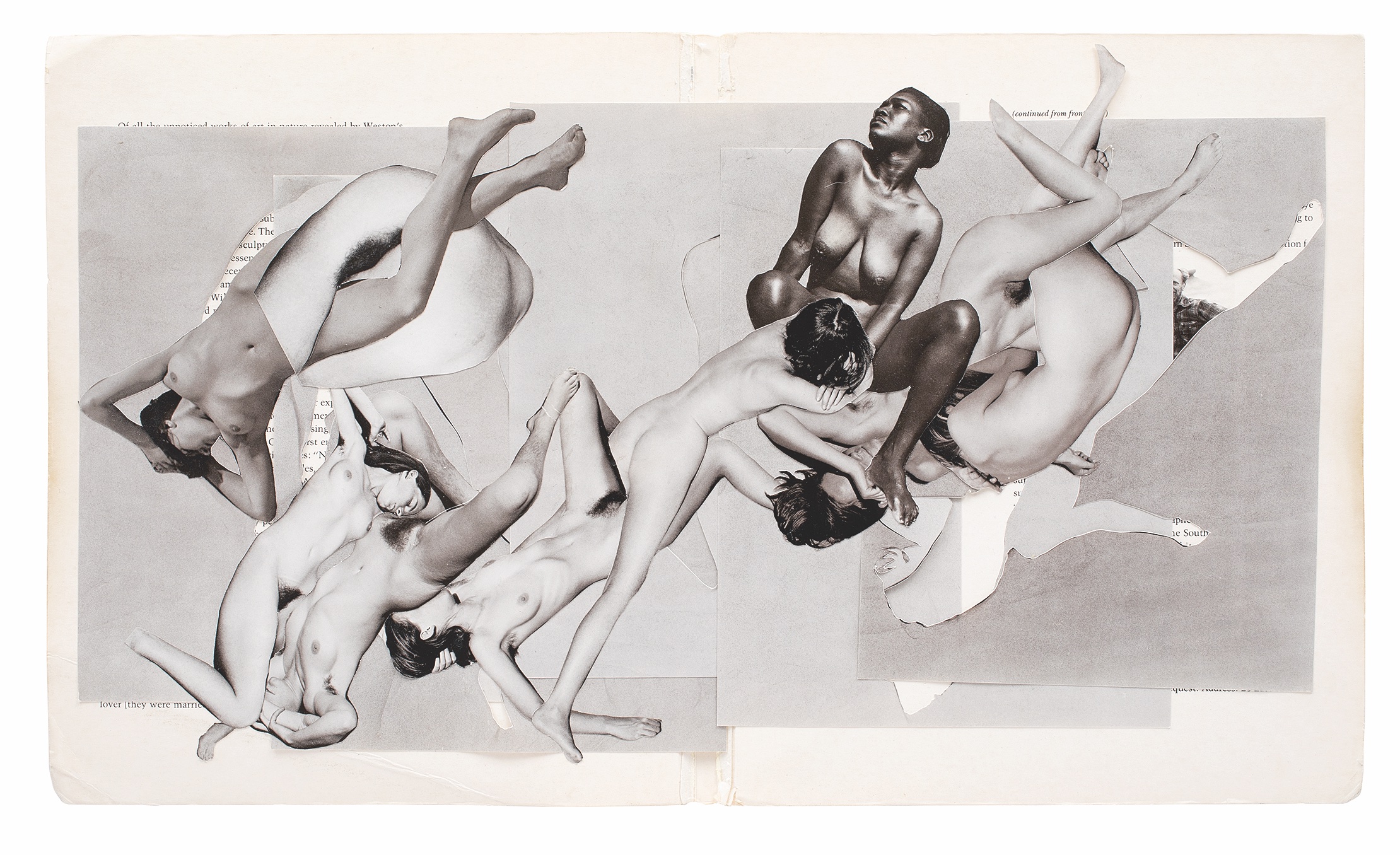

Nudes, 2021 © Justine Kurland.

After choosing a career as a photographer how does an emerging artist manage to make a living? Gem Fletcher finds out

If an outsider stumbled into the photo industry, they would encounter a world of two halves – emerging talent and world-renowned artists. What happens in between – the tough slog of cultivating and maintaining a practice – is rarely acknowledged, let alone talked about.

The photo community, such as editors, journalists, agents, publishers, gallerists and artists, are all guilty of perpetuating the highlights reel. We celebrate the projects, exhibitions, latest books and life-changing assignments without shedding light on the years of struggle and side hustles that led to that point. It’s no wonder so many young artists feel lost and confused once the initial buzz around their work wears off.

Starting out

“I wish younger artists understood how much of a long game it is to build a career,” Jess T Dugan tells me. “Things don’t happen quickly, and even if they do, sometimes you don’t want them to.” Dugan is deeply invested in supporting the next generation and remembers vividly the “gulf” they felt upon graduating. “The role models I had for successful artists were people with Guggenheim Fellowships and solo museum exhibitions. I felt like there was a 15 or 20-year gap between them and me, and I was curious to understand how to get from point A to B.”

Dugan’s strategy was, “meet everyone, learn everything”. They spent the four years between their BFA at Massachusetts College of Art & Design and MFA at Columbia College Chicago working at the Harvard Art Museums and a commercial gallery, discovering how institutions and acquisitions work.

Opting to work four long days allowed time for the last day of the working week to be spent in the darkroom, which they constructed themselves in the bedroom of their apartment. “I was aware that to build a career, I needed to centre my life around my practice,” they explain.

During Dugan’s MFA, they continued to work at institutions, taking a position at the Museum of Contemporary Photography. One of their monthly duties was to present the portfolio submissions to curators. During these sessions, they witnessed the curators’ unfiltered feedback: they saw what caught their eye and turned them off. Dugan started to understand the difference between work that was easy to sell and work that wasn’t. The experience offered vital insight and solidified the idea that museums were the home they wanted for their work.

As Dugan explains: “I always believed that this was the path I was meant to be on. Whenever a roadblock emerged, I had to figure out how to get around it. From early on, I tried to separate success as an artist from financial success or success in the market because I think those things are very different. Even when the market is working in your favour, it’s so fickle and isn’t necessarily reflective of the quality of your work.

“After I graduated, I freelanced to make money. I worked as a part-time art handler and installer. I did some assignment work. I kept trying to sell my work through galleries and applying for grants. I did not come from money, and I didn’t have a safety net. I understood early on that if I wanted to be an artist, I had to figure out the financial piece of the puzzle. Grants have been essential. I got a couple [of grants] in the $20,000 range early on [in my career], and that money went far in an affordable city like St Louis.

“There was a long incubation period where I felt like I was doing well. I had gallery shows, published a book, and had museum acquisitions, but it wasn’t translating to a living wage. It was a struggle, and part of what made [carrying on] possible for me was having a partner with a salary. I would say it’s only in the past three or four years that I’ve made any reasonable salary [from my art].”

Making a living

Figuring out how to balance making work and money puts constant pressure on emerging artists. “I remember getting advice from teachers who told me, ‘Keep your practice pure and just travel the world,’ says the artist and activist Poulomi Basu. “I thought, ‘What kind of advice is this? This is such an elitist way of doing things. Only rich people could do this because they don’t have to work.’ I had no choice. I needed to earn a living to support myself.” For Basu, finding her place in the industry was a long, painful experience. Despite grappling with institutionalised racism, gender bias and aggressive saboteurs, Basu remains defiant in her practice.

“I started as a staff photographer for Time Out in India. It was good in terms of exposure, meeting people and getting my bearings, but my salary was so poor that I used to share a dorm room with 12 other girls in Bombay. Photography in India was a highly misogynistic, male-dominated space. It was impossible to access any community because all the gatekeepers were men. Despite this, I threw myself into making a living while continuing my personal work on the side.

“I was burned out by my early twenties and had to take a break. That’s when I got a scholarship to London College of Communication. This was my foot in the door. I moved to London, and my work began to pick up. But all the documentary assignments I was given required me to be in South Asia, because commissioners just saw me as a Brown person. While understanding the nuance and sensibilities of a place is important, it doesn’t mean you should only be working there. White photographers parachute into different countries all the time. Eventually, I decided I couldn’t do it anymore. I didn’t want to be that woman put in a box that could only make work in India.”

“I’ve been bullied. I’ve been silenced. All kinds of things have happened. But you have to just keep going; there is absolutely no other way. What I’ve learned is that success is not about talent. It’s really about putting yourself out there”

Poulomi Basu

Adapting and evolving

After distancing herself from a documentary practice, Basu rerouted in the art world. She began working in film and VR alongside photography, discovering that she could support herself better by expanding her practice, as these industries had more funding. This willingness to experiment with a creative approach continues to sustain her.

Earlier this year, she presented her first NFT collection with Assembly based on her award-winning series Centralia. “I wanted to raise funds for a project I’m doing with indigenous women in India,” she says. “I’m interested in using capitalist systems to put money back into the hands of people affected by those systems. It works for me if I can align something like NFTs with something meaningful.”

Basu credits her deep self-belief and powerful vision as critical to her survival. “I’ve had terrible rough periods where people have tried to sabotage and destroy my reputation,” she says. “I’ve been bullied. I’ve been silenced. All kinds of things have happened. But you have to just keep going; there is absolutely no other way. What I’ve learned is that success is not about talent. It’s really about putting yourself out there.”

Eyes on the prize

Over the last 10 years, the rise of internet culture and social media has offered radical new opportunities for artists to get their work in front of a global audience; something previous generations could only dream of. “I wasn’t social enough to deal with the networking that seemed essential to make a living as an artist,” Alec Soth explains. “I was better at finding community through the internet. I don’t believe I’d have been able to sustain a career if the internet hadn’t come along.”

After graduating from Sarah Lawrence College, New York, Soth went back to his hometown of Minneapolis and worked in a range of photo-related roles. He spent time assisting commercial photographers before switching to darkroom work. “I began to feel that if I took pictures for a living, I was in danger of killing my passion for photography,” he shares. Like Dugan, Soth found solace working in a museum. During a nine-to-five shift, he made prints of the museum’s collection, leaving the rest of his time free for “journaling, daydreaming and taking pictures every weekend”. Soth worked at the museum for seven years, but thought he’d work there forever.

“There was relatively good funding for the arts where I live, but it’s nonetheless tricky to get your first grant. When you are unknown and unproven, people don’t trust you enough to give you money,” the Magnum photographer explains. “For several years, I applied for these grants and got rejected. With one of these fellowships, artists could sit in the audience and watch the judges make their decisions. I learned so much doing this. I realised that many factors at play are out of your control when people look at your work. One shouldn’t take rejection too personally. You need to keep trying. Eventually, I got a small grant and soon after got several more. One of these fellowships led to me make Sleeping by the Mississippi, my first successful body of work.”

Soth continues: “I worried too much about what people thought about me and my work when I started. I only found my voice when I relaxed and allowed myself to follow my intuition. My goal, in the beginning, was to publish a book. This mattered much more to me than making a living from my work. I loved the idea that someone could find my work in the future in a library. I still feel this way. Bookmaking is still my primary goal. But since bookmaking isn’t financially sustainable, I need to find time to make new work to provide for my family.”

“I began to feel that if I took pictures for a living, I was in danger of killing my passion for photography”

Alec Soth

Art market truths

For decades, artists have been taking up roles in academia to supplement their income and nurture young artists. American fine art photographer Justine Kurland says this is not just about individual survival but a crucial part of the ecosystem. “One of the ways the art market can keep functioning is by the expensive tuition fees paid by students for their undergraduate art degrees. This actually supports all the mid-career artists [who teach them]. They’re not supporting themselves by their artwork alone. Every museum might have one of my photographs, but to support yourself year in, year out, you need a day job.”

Much of Kurland’s career has been spent on the road, photographing girls against the American landscape, searching for freedom, real and imagined. Despite the financial pressures, Kurland kept shooting. “For a long time, when I first started showing [my work], I’d just live off the sales. It was very hand-to-mouth. But I was determined to stay on the road. I’d amass credit card debt and default on my student loans. I did all these things just because this is what I wanted to be doing. Then at a certain point in 2007, I realised I couldn’t keep going. I had my kid but no money. I couldn’t pay my rent or for gas.”

Indeed, one of the most dangerous perceptions surrounding a successful artist is that they are constantly selling work. In reality, one body of work might have to sustain someone for five or 10 years before making another. This is further complicated by the art market’s trend cycles. “You can be making money selling the work and then suddenly hit a phase when people are no longer interested in the type of photographs you make,” Kurland says. “So you have to get a job. Incredibly, I’ve been able to be doing this since I was 15, and I’m 52 now. I could not be luckier.”

It takes a village

Another myth we must reconcile is the notion that a successful artist is simply a product of incredible work. In fact, a whole social structure is lifting and supporting an artist from the beginning to enable their work to be recognised. “One thing I’ve realised as I’ve got older is seeing how a gallery participates in making our culture,” explains Kurland. “An artist being successful is not because they are a singular genius. There are so many people behind the scenes, running galleries, writing press releases, talking to curators and talking to collectors who contribute to someone’s success.

“It’s interesting to think about how we are all participating [in the industry]. More recently, I’ve been curating shows, writing, and participating in other ways that are not just about my own work. Teaching is an extension of that. It’s about being of service to make the world we want to live in. That’s what’s so exciting about the young artists coming up now, how their frame of reference is different and how they are breaking down some of the established power dynamics. I feel so excited by that.”

In truth, there is no singular path to follow, which makes the experience of sustaining a career in the arts so intimidating. Everyone’s idea of success is different, and no one way means you’ve made it. By unravelling this collision of vulnerabilities, motivations, happenstance, systemic inequalities, privilege and mental health, we can start to see how the messy components of life contribute to the making of the artist. “I wish I’d known that it’s about choosing an art life,” Basu explains. “When I started, I thought art was a profession – but it’s not – it’s a creative path. It’s a deeply spiritual practice.”